Case Study a Potential Trinational Protected Area: the Campo-Tecate Creek Kumiai Corridor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from San Diego's Border Wall

RESEARCH REPORT (CBP Photo/Mani Albrecht) LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL The limits to using walls for migration, drug trafficking challenges By Adam Isacson and Maureen Meyer December 2017 " The border doesn’t need a wall. It needs better-equipped ports of entry, investi- gative capacity, technology, and far more ability to deal with humanitarian flows. In its current form, the 2018 Homeland Security Appropriations bill is pursuing a wrong and wasteful approach. The ex- perience of San Diego makes that clear." LESSONS FROM SAN DIEGO'S BORDER WALL December 2017 | 2 SUMMARY The prototypes for President Trump's proposed border wall are currently sitting just outside San Diego, California, an area that serves as a perfect example of how limited walls, fences, and barriers can be when dealing with migration and drug trafficking challenges. As designated by stomsCu and Border Protection, the San Diego sector covers 60 miles of the westernmost U.S.-Mexico border, and 46 of them are already fenced off. Here, fence-building has revealed a new set of border challenges that a wall can’t fix. The San Diego sector shows that: • Fences or walls can reduce migration in urban areas, but make no difference in rural areas. In densely populated border areas, border-crossers can quickly mix in to the population. But nearly all densely populated sections of the U.S.-Mexico border have long since been walled off. In rural areas, where crossers must travel miles of terrain, having to climb a wall first is not much of a deterrent. A wall would be a waste of scarce budget resources. -

Globally Globally Ecosystem

ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY PROMISE COLLABORATION ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITYINNOVATIONCOMPETITIVENESS EFFICIENCY COLLABORATIONPROMISECREATIVITY EFFICIENCY ECONOMIC COLLABORATION BORDERLESS CREATIVITY OPPORTUNITYPROMISEBORDERLESS PROMISE OPPORTUNITY COMPETITIVENESSCREATIVITY PROMISE BORDERLESS OPPORTUNITY BORDERLESS BORDERLESS COLLABORATION INNOVATION GLOBALLY OPPORTUNITY ENTREPRENEURIAL EFFICIENCY PROMISE PROMISE ECOSYSTEM CONNECTED INNOVATION PROMISECOLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION EFFICIENCY MULTICULTURALCREATIVITY BINATIONALOPPORTUNITY BORDERLESSCREATIVITYPROMISE MULTICULTURALPROMISE EFFICIENCY ECONOMIC ECONOMIC PROMISEOPPORTUNITY ECONOMIC EFFICIENCY CREATIVITY BORDERLESS OPPORTUNITY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY ENTREPRENEURIALOPPORTUNITY PROMISE CREATIVITY PROMISE MULTICULTURAL MULTICULTURAL PROMISE PROMISE BORDERLESS CREATIVITY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY PROMISE PROMISE OPPORTUNITYCOMPETITIVENESS BINATIONAL GLOBALLY ENTREPRENEURIALBORDERLESS INNOVATION CONNECTED COMPETITIVENESS EFFICIENCY EFFICIENCY EFFICIENCY CREATIVITY ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITYINNOVATION PROMISE CREATIVITY PROMISE COLLABORATIONPROMISE INNOVATION PROMISE BORDERLESS ECONOMIC COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITYBORDERLESS COMPETITIVENESS COMPETITIVENESSCREATIVITY PROMISE ECOSYSTEM BORDERLESS BORDERLESSGLOBALLY COLLABORATION OPPORTUNITY ENTREPRENEURIAL OPPORTUNITY PROMISE CONNECTED INNOVATION PROMISECOLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION COLLABORATION EFFICIENCY MULTICULTURALCREATIVITY BINATIONALOPPORTUNITY BORDERLESS CREATIVITYPROMISE MULTICULTURALPROMISE -

Attachment B-4 San Diego RWQCB Basin Plan Beneficial Uses

Attachment B-4 San Diego RWQCB Basin Plan Beneficial Uses Regulatory_Issues_Trends.doc CHAPTER 2 BENEFICIAL USES INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................1 BENEFICIAL USES ..........................................................................................................................1 BENEFICIAL USE DESIGNATION UNDER THE PORTER-COLOGNE WATER QUALITY CONTROL ACT ..1 BENEFICIAL USE DESIGNATION UNDER THE CLEAN WATER ACT .................................................2 BENEFICIAL USE DEFINITIONS.........................................................................................................3 EXISTING AND POTENTIAL BENEFICIAL USES ..................................................................................7 BENEFICIAL USES FOR SPECIFIC WATER BODIES ........................................................................8 DESIGNATION OF RARE BENEFICIAL USE ...................................................................................8 DESIGNATION OF COLD FRESHWATER HABITAT BENEFICIAL USE ...............................................9 DESIGNATION OF SPAWNING, REPRODUCTION, AND/ OR EARLY DEVELOPMENT (SPWN) BENEFICIAL USE ...................................................................................................11 SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER POLICY ..................................................................................11 EXCEPTIONS TO THE "SOURCES OF DRINKING WATER" POLICY................................................11 -

Transboundary Issues and Solutions in the San Diego/Tijuana Border

Blurred Borders: Transboundary Impacts and Solutions in the San Diego-Tijuana Region Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 4 2 Why Do We Need to Re-think the Border Now? 6 3. Re-Defining the Border 7 4. Trans-Border Residents 9 5. Trans-National Residents 12 6. San Diego-Tijuana’s Comparative Advantages and Challenges 15 7. Identifying San Diego-Tijuana's Shared Regional Assets 18 8. Trans-Boundary Issues •Regional Planning 20 •Education 23 •Health 26 •Human Services 29 •Environment 32 •Arts & Culture 35 8. Building a Common Future: Promoting Binational Civic Participation & Building Social Capital in the San Diego-Tijuana Region 38 9. Taking the First Step: A Collective Binational Call for Civic Action 42 10. San Diego-Tijuana At a Glance 43 11. Definitions 44 12. San Diego-Tijuana Regional Map Inside Back Cover Copyright 2004, International Community Foundation, All rights reserved International Community Foundation 3 Executive Summary Blurred Borders: Transboundary Impacts and Solutions in the San Diego-Tijuana Region Over the years, the border has divided the people of San Diego Blurred Borders highlights the similarities, the inter-connections County and the municipality of Tijuana over a wide range of differ- and the challenges that San Diego and Tijuana share, addressing ences attributed to language, culture, national security, public the wide range of community based issues in what has become the safety and a host of other cross border issues ranging from human largest binational metropolitan area in North America. Of particu- migration to the environment. The ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality has lar interest is how the proximity of the border impacts the lives and become more pervasive following the tragedy of September 11, livelihoods of poor and under-served communities in both San 2001 with San Diegans focusing greater attention on terrorism and Diego County and the municipality of Tijuana as well as what can homeland security and the need to re-think immigration policy in be done to address their growing needs. -

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This Chapter Presents an Overall Summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the Water Resources on Their Reservations

4 Tribal Nations of San Diego County This chapter presents an overall summary of the Tribal Nations of San Diego County and the water resources on their reservations. A brief description of each Tribe, along with a summary of available information on each Tribe’s water resources, is provided. The water management issues provided by the Tribe’s representatives at the San Diego IRWM outreach meetings are also presented. 4.1 Reservations San Diego County features the largest number of Tribes and Reservations of any county in the United States. There are 18 federally-recognized Tribal Nation Reservations and 17 Tribal Governments, because the Barona and Viejas Bands share joint-trust and administrative responsibility for the Capitan Grande Reservation. All of the Tribes within the San Diego IRWM Region are also recognized as California Native American Tribes. These Reservation lands, which are governed by Tribal Nations, total approximately 127,000 acres or 198 square miles. The locations of the Tribal Reservations are presented in Figure 4-1 and summarized in Table 4-1. Two additional Tribal Governments do not have federally recognized lands: 1) the San Luis Rey Band of Luiseño Indians (though the Band remains active in the San Diego region) and 2) the Mount Laguna Band of Luiseño Indians. Note that there may appear to be inconsistencies related to population sizes of tribes in Table 4-1. This is because not all Tribes may choose to participate in population surveys, or may identify with multiple heritages. 4.2 Cultural Groups Native Americans within the San Diego IRWM Region generally comprise four distinct cultural groups (Kumeyaay/Diegueno, Luiseño, Cahuilla, and Cupeño), which are from two distinct language families (Uto-Aztecan and Yuman-Cochimi). -

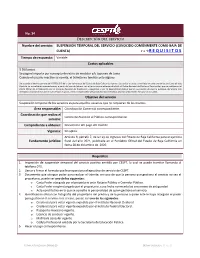

Ir a →R E Q U I S I T

No. 34 Descripción del servicio Nombre del servicio: SUSPENSIÓN TEMPORAL DEL SERVICIO (CONOCIDO COMÚNMENTE COMO BAJA DE CUENTA) Ir a R E Q U I S I T O S Tiempo de respuesta: Variable Costos aplicables $ 500 pesos Se paga el importe por concepto de retiro de medidor y/o taponeo de toma. Cuando el usuario reactive su cuenta, el trámite no tendrá costo alguno. De acuerdo al décimo párrafo del ARTÍCULO 9 de la Ley de Ingresos del Estado de Baja California, vigente: Las tarifas y cuotas contenidas en cada una de las secciones de este Capítulo, se actualizarán mensualmente, a partir del mes de febrero, con el factor que se obtenga de dividir el Índice Nacional de Precios al Consumidor, que se publique en el Diario Oficial de la Federación por el Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, o por la dependencia federal que en sustitución de ésta lo publique, del último mes inmediato anterior al mes por el cual se hace el ajuste, entre el citado índice del penúltimo mes inmediato anterior al del mismo mes que se actualiza. Objetivo del servicio Suspensión temporal de los servicios es para aquellos usuarios que no requieran de los mismos. Área responsable: Coordinación Comercial correspondiente. Coordinación que realiza el Centro de Atención al Público correspondiente. servicio: Comprobante a obtener: Documento del pago del trámite. Vigencia: No aplica. Artículo 9, párrafo 7, de la Ley de Ingresos del Estado de Baja California para el ejercicio Fundamento jurídico: fiscal del año 2021, publicada en el Periódico Oficial del Estado de Baja California en fecha 28 de diciembre de 2020. -

Designing and Establishing Conservation Areas in the Baja California-Southern California Border Region

DRAFT • NOT FOR QUOTATION Designing and Establishing Conservation Areas in the Baja California-Southern California Border Region Michael D. White, Jerre Ann Stallcup, Katherine Comer, Miguel Angel Vargas, Jose Maria Beltran- Abaunza, Fernando Ochoa, and Scott Morrison ABSTRACT The border region of Baja California in Mexico and California in the United States is a biologically diverse and unique landscape that forms a portion of one of the world’s global biodiversity hotspots. While the natural resources of this border region are continuous and interconnected, land conservation practices on either side of the international boundary that bisects this area are quite different. These binational differences place certain natural resources, ecological processes, and wildlife movement patterns at risk of falling through the cracks of conservation efforts implemented in each country. Thus, effective conservation in this region requires binational cooperation with respect to conservation planning and implementation. This paper describes the differences in land conservation patterns and land conservation mechanisms between Baja California and Alta California (Southern California). The Las Californias Binational Conservation Initiative is discussed as a case study for binational cooperation in conservation planning. Diseñando y Estableciendo Áreas de Conservación en la Región Fronteriza Baja California-Sur de California Michael D. White, Jerre Ann Stallcup, Katherine Comer, Miguel Angel Vargas, Jose Maria Beltran- Abaunza, Fernando Ochoa, y Scott Morrison RESUMEN La región fronteriza de Baja California en México y California en los Estados Unidos es un paisaje único y biológicamente diverso que forma una porción de una de las zonas clave (hotspots) de biodiversidad global en el mundo. Mientras que los recursos naturales de esta región fronteriza son continuos e interconectados, las prácticas de conservación del suelo en ambos lados de la frontera internacional que divide en dos esta área son realmente diferentes. -

San Diego & Arizona Eastern (SD&AE) Railway Fact Sheet

April 2013 Metropolitan Transit System San Diego & Arizona Eastern (SD&AE) Railway OWNER San Diego Metropolitan System (MTS) ROUTE DESCRIPTION Four (4) lines totaling 108 miles. Main Line Centre City San Diego south to San Ysidro/International Border at Tijuana. Total length 15.5 miles. This Line extends through Mexico (44.3 miles) and connects up with the Desert Line. The portion through Mexico, originally constructed as part of the Main Line, is now owned by the Mexican national railways, Ferrocarril Sonora Baja California Line. La Mesa Branch Downtown San Diego east to City of El Cajon. Total length: 16.1 miles. Coronado Branch National City south to Imperial Beach. Total length 7.2 miles. Desert Line Extends north and east from International Border (junction called Division) to Plaster City, where it joins the Union Pacific (UP) Line from El Centro. Total length: 69.9 miles. TRANSIT OPERATOR San Diego Trolley, Inc. (SDTI), a wholly subsidiary of MTS on Main Line and on the La Mesa Branch. Frequency Seven (7) days a week; 4:16 a.m. to 2:00 a.m.; 15-minute headways most of the day on Blue and Orange Lines; 7.5 minute peak hour service on Blue Line; 30-minute evenings. Patronage 97,401 average daily riders (FY 12). FREIGHT OPERATOR Private operators, San Diego & Imperial Valley (SD&IV) Railroad on three (3) lines: Main Line, La Mesa Branch, and Coronado Branch, and Pacific Imperial Railroad, Inc (PIR) on the Desert Line. Frequency Provides service as needed and at night when the San Diego Trolley is not in operation. -

Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 4 2011 Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa Alan B. Harper Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Sula Vanderplank Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, California Mark Dodero Recon Environmental Inc., San Diego, California Sergio Mata Terra Peninsular, Coronado, California Jorge Ochoa Long Beach City College, Long Beach, California Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Harper, Alan B.; Vanderplank, Sula; Dodero, Mark; Mata, Sergio; and Ochoa, Jorge (2011) "Plants of the Colonet Region, Baja California, Mexico, and a Vegetation Map of Colonet Mesa," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol29/iss1/4 Aliso, 29(1), pp. 25–42 ’ 2011, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden PLANTS OF THE COLONET REGION, BAJA CALIFORNIA, MEXICO, AND A VEGETATION MAPOF COLONET MESA ALAN B. HARPER,1 SULA VANDERPLANK,2 MARK DODERO,3 SERGIO MATA,1 AND JORGE OCHOA4 1Terra Peninsular, A.C., PMB 189003, Suite 88, Coronado, California 92178, USA ([email protected]); 2Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711, USA; 3Recon Environmental Inc., 1927 Fifth Avenue, San Diego, California 92101, USA; 4Long Beach City College, 1305 East Pacific Coast Highway, Long Beach, California 90806, USA ABSTRACT The Colonet region is located at the southern end of the California Floristic Province, in an area known to have the highest plant diversity in Baja California. -

Otay Mesa – Mesa De Otay Transportation Binational Corridor

Otay Mesa – Mesa de Otay Transportation Binational Corridor Early Action Plan Housing September 2006 Economic Development Environment TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Foundation of the Otay Mesa-Mesa de Otay Binational Corridor Strategic Plan..................................1 The Collaboration Process...........................................................................................................................1 The Strategic Planning Process and Early Actions .....................................................................................3 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................................................3 ISSUES FOR EVALUATION AND WORK PROGRAMS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................5 The Binational Study Area ..........................................................................................................................5 Issues Identified ...........................................................................................................................................5 Interactive Polling........................................................................................................................................7 Process.......................................................................................................................................................7 Results .......................................................................................................................................................8 -

San Diego County Riverside County Orange County

Chino Creek Middle Santa Ana River San Timoteo Wash Middle Santa Ana River Little Morongo Creek-Morongo Wash San Gabriel River 18070106 San Gorgonio River Headwaters Whitewater River Lower Santa Ana River Middle San Jacinto River Santa Ana River 18070203 Upper Whitewater River Temescal Wash Santiago Creek San Jacinto River 18070202 Whitewater River 18100201 San Diego Creek Lower San Jacinto River Upper San Jacinto River Newport Bay 18070204 Palm Canyon Wash O r a n g e C o u n t y RR ii vv ee rr ss ii dd ee CC oo uu nn tt yy Middle Whitewater River O r a n g e C o u n t y Middle San Jacinto River Newport Bay-Frontal Pacific Ocean San Jacinto River Deep Canyon Newport Bay-Frontal Pacific Ocean San Juan Creek Murrieta Creek Aliso Creek-Frontal Gulf of Santa Catalina Aliso Creek-San Onofre Creek 18070301 Wilson Creek Lower Whitewater River San Mateo Creek Santa Margarita River 18070302 Aliso Creek-San Onofre Creek Santa Margarita River Lower Temecula Creek Aliso Creek-Frontal Gulf of Santa Catalina Salton Sea 18100204 Santa Margarita River Upper Temecula Creek Coyote Creek Clark Valley San Felipe Creek San Onofre Creek-Frontal Gulf of Santa Catalina Camp Pendleton Bank Property Middle San Luis Rey River Upper San Luis Rey River Lower San Luis Rey River Escondido Creek-San Luis Rey River San Felipe Creek 18100203 Escondido Creek-San Luis Rey River 18070303 Borrego Valley-Borrego Sink Wash Escondido Creek San Marcos Creek-Frontal Gulf of Santa Catalina Upper Santa Ysabel Creek 8-digit HUC Upper San Felipe Creek Sevice Areas Lower Santa Ysabel -

California-Baja California Border Master Plan Update

2014California-Baja California Border Master Plan Update Actualización del Plan Maestro Fronterizo California-Baja California Technical Appendices G–H Apéndices Técnicos G–H JULY 2014 JULIO 2014 Technical Appendices G - H Table of Contents G Scoring Sheets for Ranked Projects G-1 POE Project Performance Score Sheet—New POEs ................................................................................................................2 G-2 POE Locational Criteria Score Sheet—New POEs ....................................................................................................................3 G-3 POE Project Performance Score Sheet—Existing POEs ...........................................................................................................4 G-4 POE Locational Criteria Score Sheet—Existing POEs ...............................................................................................................7 G-5 Data for Use in POE Criteria—New and Existing POEs .............................................................................................................8 G-6 Roadway Score Sheet ................................................................................................................................................................9 G-7 Interchange Score Sheet ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 G-8 Rail/Mass Transit Score Sheet ...............................................................................................................................................