How Lower Canada Won the War of 1812 Text of a Speech to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

Report of the Department of Militia and Defence Canada for the Fiscal

The documents you are viewing were produced and/or compiled by the Department of National Defence for the purpose of providing Canadians with direct access to information about the programs and services offered by the Government of Canada. These documents are covered by the provisions of the Copyright Act, by Canadian laws, policies, regulations and international agreements. Such provisions serve to identify the information source and, in specific instances, to prohibit reproduction of materials without written permission. Les documents que vous consultez ont été produits ou rassemblés par le ministère de la Défense nationale pour fournir aux Canadiens et aux Canadiennes un accès direct à l'information sur les programmes et les services offerts par le gouvernement du Canada. Ces documents sont protégés par les dispositions de la Loi sur le droit d'auteur, ainsi que par celles de lois, de politiques et de règlements canadiens et d’accords internationaux. Ces dispositions permettent d'identifier la source de l'information et, dans certains cas, d'interdire la reproduction de documents sans permission écrite. u~ ~00 I"'.?../ 12 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 36 A. 1922 > t-i REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF MILITIA AND DEFENCE CANADA FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING MARCH 31 1921 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT H.Q. 650-5-21 100-11-21 OTTAWA F. A. ACLAND PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1921 [No. 36-1922] 12 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 36 A. 1922 To General His Excellency the Right HQnourable Lord Byng of Vimy, G.C.B., G.C.M.G., M.V.0., Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. -

A National Monument to Laura Secord : Why It Should Be Erected, An

138324 PRICE 10 CENTS. I A NATIONAL MONUMENT | TO €1 ,. LAURA SECORD,. I i WHY IT SHOULD BE ERECTED. I AN" APPEAL TO THE riA)PLE I O F C A N A D A F R CM T H E %i I I.AURA SECORD NATIOXAL MONUMENT COMMITTKi:. I I 44 ft [Being a paper read by R. E. A. Land before the U. E. L. Association of Ontario, October 4th, 1901.) Toronto : . KAHAM & Co. Church Street, igoi. iiw'!!!'iw<"i«»>»e] j*iirf'iiiii»ii!iwii;|;«wi»>i<%C'i'»i'i!'i»''> «i'>»«il'"i»'>«''"'i» i'",S'»"-"i PRICE, 10 CENTS. A NATIONAL MONUMENT TO ..LAURA SECORD.. WHY IT SHOULD BE ERECTED. AN APPEAL TO THE PEOPLE OF CANADA FROM THE LAURA SECORD NATIOxNAL MONUMENT COMMITTEE. (Being a paper read by R. E. A. Land before the U. E. L. Association of Ontario, October 4th, 1901.) Toronto : Printed by Imrif, Graham & Co., 31 Church Street, iqoi. The Story of Laura Secord And Other Canadian Reminiscences MRS. J. G. CURRIE ST. CATHARINES IN CLOTH, WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS $1.50 POSTPAID. It is the author's intention to apply the proceeds of sales of her book after the cost of publication to the Monument Fund. Copies may be obtAfned -from Mrs. Currie. Help for the Monument. - It is your Privilegre to g^ive it. The Laura Secord National Monument Com- mittee, created under the auspices of the United Empire Loyalists' Association of Ontario, having taken in hand the erection of a National Monument at Queenston, Ontario, to the memory of LAURA SECORD The Heroine of Upper Canada calls upon the Canadian people for help. -

The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial

182-199 120820 11/1/04 2:57 PM Page 182 Chapter 13 The North-West Rebellion 1885 Riel on Trial It is the summer of 1885. The small courtroom The case against Riel is being heard by in Regina is jammed with reporters and curi- Judge Hugh Richardson and a jury of six ous spectators. Louis Riel is on trial. He is English-speaking men. The tiny courtroom is charged with treason for leading an armed sweltering in the heat of a prairie summer. For rebellion against the Queen and her Canadian days, Riel’s lawyers argue that he is insane government. If he is found guilty, the punish- and cannot tell right from wrong. Then it is ment could be death by hanging. Riel’s turn to speak. The photograph shows What has happened over the past 15 years Riel in the witness box telling his story. What to bring Louis Riel to this moment? This is the will he say in his own defence? Will the jury same Louis Riel who led the Red River decide he is innocent or guilty? All Canada is Resistance in 1869-70. This is the Riel who waiting to hear what the outcome of the trial was called the “Father of Manitoba.” He is will be! back in Canada. Reflecting/Predicting 1. Why do you think Louis Riel is back in Canada after fleeing to the United States following the Red River Resistance in 1870? 2. What do you think could have happened to bring Louis Riel to this trial? 3. -

Canadian Military Journal, Issue 13, No 2

Vol. 13, No. 2 , Spring 2013 CONTENTS 3 EDITOR’S CORNER 4 VALOUR 6 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR INTERDEPARTMENTAL CIVILIAN/MILITARY COOPERATION 8 CANADA’S WHOLE OF GovernMENT MISSION IN AFghanistan - LESSONS LEARNED by Kimberley Unterganschnigg Cover TECHNOLOGICAL INNOVATION A two-seater CF-188 Hornet flies over the Parc des Laurentides en 17 ACTIVE Protection SYSTEMS: route to the Valcartier firing A Potential JacKpot to FUTURE ARMY Operations range, 22 November 2012. by Michael MacNeill Credit : DND Photo BN2012-0408-02 by Corporal Pierre Habib SCIENCE AND THE MILITARY 26 AN Overview OF COMPLEXITY SCIENCE AND its Potential FOR MilitarY Applications by Stéphane Blouin MILITARY HISTORY 37 THE Naval Service OF CANADA AND OCEAN SCIENCE by Mark Tunnicliffe 46 Measuring THE Success OF CANADA’S WARS: THE HUNDRED DAYS OFFENSIVE AS A CASE STUDY by Ryan Goldsworthy CANADA’S WHOLE OF 57 “FIGHT OR FarM”: CANADIAN FarMERS AND GOVERNMENT MISSION THE DILEMMA OF THE WAR EFFort IN WORLD WAR I (1914-1918) IN AFGHANIstan - by Mourad Djebabla LESSONS LEARNED VIEWS AND OPINIONS 68 CANADA’S FUTURE FIGHTER: A TRAINING CONCEPT OF Operations by Dave Wheeler 74 REDEFINING THE ARMY Reserves FOR THE 21ST CENTURY by Dan Doran 78 NCM Education: Education FOR THE FUTURE Now by Ralph Mercer COMMENTARY ACTIVE PROTECTION 82 What ARE THE Forces to DO? SYSTEMS: A POTENTIAL by Martin Shadwick JACKPOT TO FUTURE ARMY OPERatIONS 86 BOOK REVIEWS Canadian Military Journal / Revue militaire canadienne is the official professional journal of the Canadian Forces and the Department of National Defence. It is published quarterly under authority of the Minister of National Defence. -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism. -

A. Booth Packing Company

MARINE SUBJECT FILE GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION Milwaukee Public Library/Wisconsin Marine Historical Society page 1 Current as of January 7, 2019 A. Booth Packing Company -- see Booth Fleets Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987 (includes Antiquities Act of 1906) Abitibi Fleet -- see Abitibi Power and Paper Company Abitibi Power and Paper Company Acme Steamship Company Admiralty Law African Americans Aids to Navigation (Buoys) Aircraft, Sunken Alger Underwater Preserve -- see Underwater parks and preserves Algoma Central Railway Marine Algoma Steamship Co. -- see Algoma Central Railway (Marine Division) Algoma Steel Corporation Allan Line (Royal Mail Steamers) Allen & McClelland (shipbuilders) Allen Boat Shop American Barge Line American Merchant Marine Library Assn. American Shipbuilding Co. American Steamship Company American Steel Barge Company American Transport Lines American Transportation Company -- see Great Lakes Steamship Company, 1911-1957 Anchor Line Anchors Andrews & Sons (Shipbuilders) Andrie Inc. Ann Arbor (Railroad & Carferry Co.) Ann Arbor Railway System -- see Michigan Interstate Railway Company Antique Boat Museum Antiquities Act of 1906 see Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987 Apostle Islands -- see Islands -- Great Lakes Aquamarine Armada Lines Arnold Transit Company Arrivals & Departures Association for Great Lakes Maritime History Association of Lake Lines (ALL) Babcock & Wilcox Baltic Shipping Co. George Barber (Shipbuilder) Barges Barry Transportation Company Barry Tug Line -- see Barry Transportation Company Bassett Steamship Company MARINE SUBJECT FILE GREAT LAKES MARINE COLLECTION Milwaukee Public Library/Wisconsin Marine Historical Society page 2 Bay City Boats Inc. Bay Line -- see Tree Line Navigation Company Bay Shipbuilding Corp. Bayfield Maritime Museum Beaupre, Dennis & Peter (Shipbuilders) Beaver Island Boat Company Beaver Steamship Company -- see Oakes Fleets Becker Fleet Becker, Frank, Towing Company Bedore’s, Joe, Hotel Ben Line Bessemer Steamship Co. -

Naval Medical Operations at Kingston During the War of 1812

Canadian Military History Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 5 2009 Naval Medical Operations at Kingston during the War of 1812 Gareth A. Newfield Canadian War Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Newfield, Gareth A. "Naval Medical Operations at Kingston during the War of 1812." Canadian Military History 18, 1 (2009) This Canadian War Museum is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Newfield: Naval Medical Operations Naval Medical Operations at Kingston during the War of 1812 Gareth Newfield ritish naval medicine in Kingston, Furthermore, operations in Europe Frederick, immediately across the BOntario is a peripheral and against Napoleonic France dominated Cataraqui River commencing shortly seldom-explored aspect of the War the medical resources of the British afterwards. Little effort, however, of 1812 on the Great Lakes. Men Army and Royal Navy for much of was made to provide the Marine hospitalized ashore disappeared the war against the United States. Department with its own medical from history, and consequently our Medical officers at the Kingston infrastructure. As a division of the understanding of the circumstances and Point Frederick shore hospitals British Army rather than the Royal and conditions under which they faced shortages of facilities, staff Navy, its seamen were expected received medical care is quite poor. and supplies throughout the War of to rely upon the military hospital The practice of naval medicine 1812. -

The Play That Delighted Sold-Out Houses at Opens At

!"#$%&''()(*+, The Play that delighted sold-out houses at THE STRATFORD FESTIVAL opens at SOULPEPPER’s home The YOUNG CENTRE April 2013, two hundred years to the month WKHRULJLQDOGUDPDLQÁDPHGWKHWRZQRI<RUN VideoCabaret presents in association with the Young Centre for the Performing Arts !"#$%& '()*)+ :ULWWHQDQG'LUHFWHGE\0LFKDHO+ROOLQJVZRUWK Opening April 8, 2013 ,Q7RURQWR·V+LVWRULF'LVWLOOHU\'LVWULFW 6HDVRQ6SRQVRU%02)LQDQFLDO*URXS 6LU,VDDF%URFN 5LFKDUG&ODUNLQ /DXUD6HFRUG /LQGD3U\VWDZVND DQG&DSWDLQ)LW]JLEERQ 0DF)\IH *HQHUDO+DUULVRQ 5LFKDUG$ODQ&DPSEHOO 7HFXPVHK $QDQG5DMDUDP 7KH3URSKHW 0LFKDHOD:DVKEXUQ 6ROGLHUV *UHJ&DPSEHOO-DFRE-DPHV 3UHV0DGLVRQ 'ROO\ -DFRE-DPHV/LQGD3U\VWDZVND *HQ:LQÀHOG6FRWW 5&ODUNLQ &DSWDLQ)LW]JLEERQ 0)\IH 6ROGLHUV )XOO&RPSDQ\ 6WUDWIRUGSUHVHQWDWLRQ3KRWRJUDSK\E\0LFKDHO&RRSHU When America declares war on Britain and her empire, a Native Praise for !"#$%& '( )*)+,at The Stratford Festival confederation led by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh defends its own territory by joining in the defence of Canada. After three years of “A knockout ... The writing (by Michael Hollingsworth) is “A cross between Spitting Image and the theatre of bloodshed on land & lake, the Yankees have burned York, the Yorkees pungent, the staging (also by Hollingsworth) is brilliant, Bertolt Brecht ... it’s a rollicking good ride.” have burned Washington, and everyone has burned the Natives. the set and lighting (Andy Moro) are superbly - The American Conservative precise and economic, the costumes (Astrid Janson) are even more superbly garish.” “If I were to recommend one must-see production 6WDUULQJPAUL BRAUNSTEIN, AURORA BROWNE, RICHARD ALAN CAMPBELL, RICHARD CLARKIN - National Post at this year’s 60th season of the Stratford Festival, MAC FYFE, DEREK GARZA, JACOB JAMES, LINDA PRYSTAWSKA it would be VideoCabaret’s The War of 1812.” $VVRFLDWH'LUHFWRUDEANNE TAYLOR6HWDQG/LJKWLQJANDY MORO “A rollicking, radical, rambunctious retelling of the -Sarah B. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

Reliving History: Fenian Raids at Old Fort Erie and Ridgeway

War-hardened Fenians had recently survived the U.S. Civil War, so they knew the benefits of moving to the cover of farmers’ fences. They took advantage of every opportunity at the Battle of Ridgeway and old Fort Erie. hey arrive in buses, and picks up his flintlock, he’s Reliving History: vans and cars, from the a member of the 1812 British U.S.A. and from across 49th Regiment of Foot Grena- Canada. Men and wom- diers. Fenian Raids Ten range from pre-teen drum- Everyone in combat signs mer boys and flag bearers, up a waiver for personal liability, to very retired seniors. They all and each of their weapons is at Old Fort Erie share a passion for history, an inspected for cleanliness, func- appreciation for the camarade- tion and the trigger safety. rie and a love of living under As he waits his turn, Ful- and Ridgeway canvas. They’re teachers, civic ton says few re-enactors carry workers, law enforcers, and original flintlocks or percus- Words & photos by Chris Mills myriad other real life profes- sion cap muskets. Pretty good sionals. But put a black powder replicas made in India sell for rifle in their hands, and this is $500 or $600, but Fulton and how they spend the weekend. his crew all carry genuine Ital- Women and children at war: women fought in 19th-century battles, Fenian re-enactors march from their camp to the battlefield. Private Dave Fulton, 54, is a ian Pedersoli replicas worth sometimes disguised as males. This woman is a fife player in the The flag of green with a gold harp shows artistic licence; it Toronto civic worker, but when about $1,200.“I’m a history regimental band, behind a boy flag bearer. -

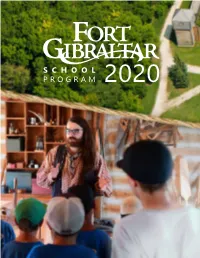

S C H O O L Program

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date.