King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of the Auditor General of Pakistan

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISASTER MANAGEMENT ORGANIZATIONS (FEDERAL) AUDIT YEAR 2018-19 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ........................................................................... i PREFACE .............................................................................................................. iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................v SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS .......................................................................... viii I Audit Work Statistics .......................................................................... viii II Audit observations regarding Financial Management ....... viii III Outcome Statistics .......................................................................... ix IV Table of Irregularities pointed out ..............................................x V Cost-Benefit ........................................................................................x CHAPTER-1 Public Financial Management Issues ..............................................................1 Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA) ..................1 1.1 Audit Paras .............................................................................................1 CHAPTER-2 Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA) ..................7 2.1 Introduction of Authority .......................................................................7 2.2 Comments on Budget -

Pakistan-U.S. Relations

Pakistan-U.S. Relations K. Alan Kronstadt Specialist in South Asian Affairs July 1, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33498 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Pakistan-U.S. Relations Summary A stable, democratic, prosperous Pakistan actively combating religious militancy is considered vital to U.S. interests. U.S. concerns regarding Pakistan include regional and global terrorism; Afghan stability; democratization and human rights protection; the ongoing Kashmir problem and Pakistan-India tensions; and economic development. A U.S.-Pakistan relationship marked by periods of both cooperation and discord was transformed by the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States and the ensuing enlistment of Pakistan as a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. Top U.S. officials praise Pakistan for its ongoing cooperation, although long-held doubts exist about Islamabad’s commitment to some core U.S. interests. Pakistan is identified as a base for terrorist groups and their supporters operating in Kashmir, India, and Afghanistan. Pakistan’s army has conducted unprecedented and, until recently, largely ineffectual counterinsurgency operations in the country’s western tribal areas, where Al Qaeda operatives and pro-Taliban militants are said to enjoy “safe haven.” U.S. officials increasingly are concerned that indigenous religious extremists represent a serious threat to the stability of the Pakistani state. The United States strongly encourages maintenance of a bilateral cease-fire and a continuation of substantive dialogue between Pakistan and neighboring India, which have fought three wars since 1947. A perceived Pakistan-India nuclear arms race has been the focus of U.S. -

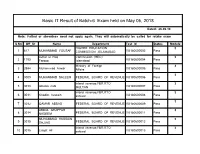

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam Held on May 05, 2018

Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam S.No Off_Sr Name Department Test Id Status Module HIGHER EDUCATION 3 1 617 MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COMMISSION ,ISLAMABAD VU180600002 Pass Azhar ul Haq Commission (HEC) 3 2 1795 Farooq Islamabad VU180600004 Pass Ministry of Foreign 3 3 2994 Muhammad Anwar Affairs VU180600005 Pass 3 4 3009 MUHAMMAD SALEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600006 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 5 3010 Ghulan nabi MULTAN VU180600007 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 6 3011 Khadim hussain sahiwal VU180600008 Pass 3 7 3012 QAMAR ABBAS FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600009 Pass ABDUL GHAFFAR 3 8 3014 NADEEM FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600011 Pass MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN 3 9 3015 SAJJAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600012 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 10 3016 Liaqat Ali sahiwal VU180600013 Pass inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 11 3017 Tariq javed sahiwal VU180600014 Pass 3 12 3018 AFTAB AHMAD FEDERAL BOARD OF REVENUE VU180600015 Pass Basic IT Result of Batch-6 Exam held on May 05, 2018 Dated: 26-06-18 Muhammad inam-ul- inland revenue,FBR,RTO 3 13 3019 haq MULTAN VU180600016 Pass Ministry of Defense (Defense Division) 3 Rawalpindi. 14 4411 Asif Mehmood VU180600018 Pass 3 15 4631 Rooh ul Amin Pakistan Air Force VU180600022 Pass Finance/Income Tax 3 16 4634 Hammad Qureshi Department VU180600025 Pass Federal Board Of Revenue 3 17 4635 Arshad Ali Regional Tax-II VU180600026 Pass 3 18 4637 Muhammad Usman Federal Board Of Revenue VU180600027 -

General Zia Ul Haq Biography Pdf

General zia ul haq biography pdf Continue Zia в качестве президента, около 19856th Президент ПакистанаВ офисе16 сентября 1978 - 17 августа 1988Премьер-министрМухаммад Хан JunejoPreced поfazal Илахи ChaudhrySucceed поГхулам Исhaq KhanChief из штабаﻣﺤﻤﺪ ﺿﯿﺎء اﻟﺤﻖПакистанский лидер Мухаммад Зия-уль-Haq армии1 марта 1976 - 17 августа 1988ПрежденоTikka KhanSucceed поМирза Аслам Бег Личные данныеРожденные (1924-08-12)12 Августа 1924Jalandhar, Пенджаб, IndiaDied17 августа 1988(1988-08-17) (в возрасте 64 лет)Бахавалпур, Пенджаб, PakistanCause аварии самолетаairResting местоФайсал мечеть, ИсламабадНациональность Индийский (1924-1947) Пакистанский (1947-1988)Супруга (ы)Бегум Шафик Зия (1950-1988; его смерть) Колледж Стивена, ДелиВое командование армии США и Генеральный штаб CollegeMilitary serviceAllegiance Индия ПакистанБранч/служба индийской армии Пакистана ArmyYears службы1943-1988Великорд GeneralUnit22 кавалерия, Армейский бронетанковый корпус (PA - 1810)Команды2-й независимой бронетанковой бригады1-й бронетанковой дивизииII ударный корпусБаз армейского штабаBattles/warsWorld War IIIndo-Пакистанская война 1965индо-пакистанской войны 1971Совет-афганская война Эта статья является частью серии оМухаммад Зия-уль-Хак Ранняя жизнь Военный переворот Зия администрации Политические взгляды Худуд Указы исламизации Экономическая политика Выборы 1985 Президент Пакистана Нарушения прав человека Референдум в 1984 Восьмая поправка Ojhri Cantt катастрофы Закат Совета 1978 резня в Мултан колонии Textile Mills Death State Funeral Shafi-your-Rehman Commission Case Explosion Mango Gallery: Photo, Sound, Video vte Muhammad zia-ul-Haq (August 12, 1924-August 17, 1988) - Pakistani four-star general became Pakistan's sixth president after declaring martial law in 1977. He served as head of state from 1978 until his death in 1988. He remains the longest-reigning head of state. Educated at Delhi University, zia saw action in World War II as an Indian army officer in Burma and Malaya before choosing Pakistan in 1947 and fighting as a tank commander in the Indo-Pakistan War of 1965. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

Pakistan S Strategic Blunder at Kargil, by Brig Gurmeet

Pakistan’s Strategic Blunder at Kargil Gurmeet Kanwal Cause of Conflict: Failure of 10 Years of Proxy War India’s territorial integrity had not been threatened seriously since the 1971 War as it was threatened by Pakistan’s ill-conceived military adventure across the Line of Control (LoC) into the Kargil district of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) in the summer months of 1999. By infiltrating its army soldiers in civilian clothes across the LoC, to physically occupy ground on the Indian side, Pakistan added a new dimension to its 10-year-old ‘proxy war’ against India. Pakistan’s provocative action compelled India to launch a firm but measured and restrained military operation to clear the intruders. Operation ‘Vijay’, finely calibrated to limit military action to the Indian side of the LoC, included air strikes from fighter-ground attack (FGA) aircraft and attack helicopters. Even as the Indian Army and the Indian Air Force (IAF) employed their synergised combat potential to eliminate the intruders and regain the territory occupied by them, the government kept all channels of communication open with Pakistan to ensure that the intrusions were vacated quickly and Pakistan’s military adventurism was not allowed to escalate into a larger conflict. On July 26, 1999, the last of the Pakistani intruders was successfully evicted. Why did Pakistan undertake a military operation that was foredoomed to failure? Clearly, the Pakistani military establishment was becoming increasingly frustrated with India’s success in containing the militancy in J&K to within manageable limits and saw in the Kashmiri people’s open expression of their preference for returning to normal life, the evaporation of all their hopes and desires to bleed India through a strategy of “a thousand cuts”. -

Pakistan's Military Elite Paul Staniland University of Chicago Paul

Pakistan’s Military Elite Paul Staniland University of Chicago [email protected] Adnan Naseemullah King’s College London [email protected] Ahsan Butt George Mason University [email protected] DRAFT December 2017 Abstract: Pakistan’s Army is a very politically important organization. Yet its opacity has hindered academic research. We use open sources to construct unique new data on the backgrounds, careers, and post-retirement activities of post-1971 Corps Commanders and Directors-General of Inter-Services Intelligence. We provide evidence of bureaucratic predictability and professionalism while officers are in service. After retirement, we show little involvement in electoral politics but extensive involvement in military-linked corporations, state employment, and other positions of influence. This combination provides Pakistan’s military with an unusual blend of professional discipline internally and political power externally - even when not directly holding power. Acknowledgments: Michael Albertus, Jason Brownlee, Christopher Clary, Hamid Hussain, Sana Jaffrey, Mashail Malik, Asfandyar Mir, Vipin Narang, Dan Slater, and seminar participants at the University of Texas at Austin have provided valuable advice and feedback. Extraordinary research assistance was provided by Yusuf al-Jarani and Eyal Hanfling. 2 This paper examines the inner workings of Pakistan’s army, an organization central to questions of local, regional, and global stability. We investigate the organizational politics of the Pakistan Army using unique individual-level -

Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth

Winner List Chief Minister Self Employment Scheme for Unemployed Educated Youth Sargodha Division NIC ApplicantName GuardianName Address WinOrder Bhakkar Bhakkar (Bolan) Key Used: kjhjkbghj 3810106547003 NIAZ HUSSAIN KHUDA BUX MOH MASOOM ABAD BHK TEH&DISTT 1 BHK 3810196198719 M RIZWAN GHOURI M RAMZAN MOH PIR BHAR SHAH NEAE MASJID 2 SADIQ E AKBAR GADOLA 3810122593641 M MUSAWAR HAYAT MALIK MUHAMMAD HAYAT H # 295-B WARD NO 8 CHISHTY 3 HOTLE CHIMNY MOHALLAH 3810106836423 ATIF RANA SARDAR AHMED KHAN NEAR HABIB MASJID BHEAL ROAD 4 BHAKAR 3810102670713 GHULAM MUSTAFA GHULAM HUSSAIN CHAH MUHAMMAD HUSSAIN WALA 5 BHAKKAR 3810192322799 MUHAMMAD IMRAN MUHAMMAD RAMZAN NEAR DHAQ HOSPITAL HOUSE NO 1 6 MOHLAH DOCTORS COLON 3810123681439 MOHAMMAD EJAZ AAMIR MALIK MOHAMMAD AFZAL KHAN CHAK NO 57-58 1M.L SRIOY MUHAJIR 7 TEHS AND DISTT BH 3810126285501 RANA MUDASSAR IQBAL MUHAMMAD IQBAL H NO 134 MOHALLAH SHAHANI NEAR 8 RAILWAY HOSPITAL BH 3810106764713 IFTIKHAR AHMED MUSHTAQ AHMED CHAK NO 48/T.D.A P/O CHAK NO 9 47/T.D.A TEHSIL & DIS 3810106335583 Abdul Rehman Malik Ghulam Hussain Cha Hussain wala Thal R/o Chhima Distt. 10 Bhakkar 3810130519177 ZULFIQAR ALI GHULAM MUHAMMAD KHAN CHAH KHANANWALA P/O KHANSAR 11 TEH & DISTT BHAKKAR 3810105774409 ABDUL RAHIM JEEVAN CHAK NO 203/TDA SRLAY MUHAJIR 12 TEH. & DISTT. BHAKKA 3810126378319 MUHAMMAD ADNAN IQBAL MUHAMMAD IQBAL H NO 3/99 Q TYPE MONDI TOWN 13 BHAKKAR 3620144603149 KHA;LID RAZA MUHAMMAD RAZA CHAK NO 382/WB P.O SAME TEH 14 DUNYA PUR 3810156112899 AFTAB HUSSAIN KHAN FIAZ HUSSAIN KHAN CHAH BAHADUR WALA P/O KHANSAR -

Pakistan's Army

Pakistan’s Army: New Chief, traditional institutional interests Introduction A year after speculation about the names of those in the race for selection as the new Army Chief of Pakistan began, General Qamar Bajwa eventually took charge as Pakistan's 16th Chief of Army Staff on 29th of November 2016, succeeding General Raheel Sharif. Ordinarily, such appointments in the defence services of countries do not generate much attention, but the opposite holds true for Pakistan. Why this is so is evident from the popular aphorism, "while every country has an army, the Pakistani Army has a country". In Pakistan, the army has a history of overshadowing political landscape - the democratically elected civilian government in reality has very limited authority or control over critical matters of national importance such as foreign policy and security. A historical background The military in Pakistan is not merely a human resource to guard the country against the enemy but has political wallop and opinions. To know more about the power that the army enjoys in Pakistan, it is necessary to examine the times when Pakistan came into existence in 1947. In 1947, both India and Pakistan were carved out of the British Empire. India became a democracy whereas Pakistan witnessed several military rulers and still continues to suffer from a severe civil- military imbalance even after 70 years of its birth. During India’s war of Independence, the British primarily recruited people from the Northwest of undivided India which post partition became Pakistan. It is noteworthy that the majority of the people recruited in the Pakistan Army during that period were from the Punjab martial races. -

Pakistan Courting the Abyss by Tilak Devasher

PAKISTAN Courting the Abyss TILAK DEVASHER To the memory of my mother Late Smt Kantaa Devasher, my father Late Air Vice Marshal C.G. Devasher PVSM, AVSM, and my brother Late Shri Vijay (‘Duke’) Devasher, IAS ‘Press on… Regardless’ Contents Preface Introduction I The Foundations 1 The Pakistan Movement 2 The Legacy II The Building Blocks 3 A Question of Identity and Ideology 4 The Provincial Dilemma III The Framework 5 The Army Has a Nation 6 Civil–Military Relations IV The Superstructure 7 Islamization and Growth of Sectarianism 8 Madrasas 9 Terrorism V The WEEP Analysis 10 Water: Running Dry 11 Education: An Emergency 12 Economy: Structural Weaknesses 13 Population: Reaping the Dividend VI Windows to the World 14 India: The Quest for Parity 15 Afghanistan: The Quest for Domination 16 China: The Quest for Succour 17 The United States: The Quest for Dependence VII Looking Inwards 18 Looking Inwards Conclusion Notes Index About the Book About the Author Copyright Preface Y fascination with Pakistan is not because I belong to a Partition family (though my wife’s family Mdoes); it is not even because of being a Punjabi. My interest in Pakistan was first aroused when, as a child, I used to hear stories from my late father, an air force officer, about two Pakistan air force officers. In undivided India they had been his flight commanders in the Royal Indian Air Force. They and my father had fought in World War II together, flying Hurricanes and Spitfires over Burma and also after the war. Both these officers later went on to head the Pakistan Air Force. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law.