An Illustrated Aristotelian Manuscript from the Crusader States. Some Preliminary Remarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index Nominum

Index Nominum Abualcasim, 50 Alfred of Sareshal, 319n Achillini, Alessandro, 179, 294–95 Algazali, 52n Adalbertus Ranconis de Ericinio, Ali, Ismail, 8n, 132 205n Alkindi, 304 Adam, 313 Allan, Mowbray, 276n Adam of Papenhoven, 222n Alne, Robert, 208n Adamson, Melitta Weiss, 136n Alonso, Manual, 46 Adenulf of Anagni, 301, 384 Alphonse of Poitiers, 193, 234 Adrian IV, pope, 108 Alverny, Marie-Thérèse d’, 35, 46, Afonso I Henriques, king of Portu- 50, 53n, 93, 147, 177, 264n, 303, gal, 35 308n Aimery, archdeacon of Tripoli, Alvicinus de Cremona, 368 105–6 Amadaeus VIII, duke of Savoy, Alberic of Trois Fontaines, 100–101 231 Albert de Robertis, bishop of Ambrose, 289 Tripoli, 106 Anastasius IV, pope, 108 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Anti- Anatoli, Jacob, 113 och, 73, 77n, 86–87, 105–6, 122, Andreas the Jew, 116 140 Andrew of Cornwall, 201n Albert of Schmidmüln, 215n, 269 Andrew of Sens, 199, 200–202 Albertus Magnus, 1, 174, 185, 191, Antonius de Colell, 268 194, 212n, 227, 229, 231, 245–48, Antweiler, Wolfgang, 70n, 74n, 77n, 250–51, 271, 284, 298, 303, 310, 105n, 106 315–16, 332 Aquinas, Thomas, 114, 256, 258, Albohali, 46, 53, 56 280n, 298, 315, 317 Albrecht I, duke of Austria, 254–55 Aratus, 41 Albumasar, 36, 45, 50, 55, 59, Aristippus, Henry, 91, 329 304 Arnald of Villanova, 1, 156, 229, 235, Alcabitius, 51, 56 267 Alderotti, Taddeo, 186 Arnaud of Verdale, 211n, 268 Alexander III, pope, 65, 150 Ashraf, al-, 139n Alexander IV, pope, 82 Augustine (of Hippo), 331 Alexander of Aphrodisias, 311, Augustine of Trent, 231 336–37 Aulus Gellius, -

Download July 2016 Updated Hyperlinks Masterlist

ms_shelfmark ms_title ms_dm_link Add Ch 54148 Bull of Pope Alexander III relating to Kilham, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_Ch_54148&index=0 Yorkshire Add MS 5228 Sketches and notes by Albrecht Dürer http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_5228 Add MS 5229 Sketches and notes by Albrecht Dürer http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_5229 Add MS 5231 Sketches and notes by Albrecht Dürer http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_5231 Add MS 5411 Lombard Laws http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_5411 Add MS 5464 Draft treatise against papal supremacy by http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_5464 Edward VI Add MS 5474 Le Roman de Tristan en prose http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_5474 Add MS 10292 Lancelot Grail http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_10292 Add MS 10293 Lancelot Grail http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_10293 Add MS 10294/1 f. 1 (renumber as Lancelot Grail http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=1&ref=Add_MS_10294/1 Add MS 10294/1) Add MS 10294 Lancelot-Grail (The Prose Vulgate Cycle) http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_10294 Add MS 10546/1 Detached binding formerly attached to Add MS http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_10546/1 10546 (the 'Moutier-Grandval Bible') Add MS 11883 Petrus Riga, Aurora http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Add_MS_11883 -

The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople During the Frankish Era (1196-1303)

The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the Frankish Era (1196-1303) ELENA KAFFA A thesis submitted to the University of Wales In candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Archaeology University of Wales, Cardiff 2008 The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the Frankish Era (1196-1303) ELENA KAFFA A thesis submitted to the University of Wales In candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Archaeology University of Wales, Cardiff 2008 UMI Number: U585150 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585150 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This thesis provides an analytical presentation of the situation of the Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the earlier part of the Frankish Era (1196 - 1303). It examines the establishment of the Latin Church in Constantinople, Cyprus and Achaea and it attempts to answer questions relating to the reactions of the Greek Church to the Latin conquests. -

Translators Role During Transmissing Process Of

IJISET - International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, Vol. 3 Issue 3, March 2016. www.ijiset.com ISSN 2348 – 7968 The Intermediary Role of The Arabs During The Middle Ages In The Transmission Of Ancient Scientific Knowledge To Europe Prof. Dr. Luisa María Arvide Cambra Department of Philology.University of Almería. Almería. Spain Abstract One of the most important roles of the Islamic civilization is that of having transmitted the Ancient 2.Translators from Greek into Arabic culture to the European Renaissance through the process of translation into Arabic of scientific There were two great schools of translation knowledge of Antiquity, i.e. the Sanskrit, the Persian, from Greek into Arabic: that of the Christian the Syriac, the Coptic and, over all, the Greek, during th th Nestorians of Syria and that of the Sabeans of the 8 and 9 centuries. Later, this knowledge was Harran [4]. enriched by the Arabs and was transferred to Western Europe thanks to the Latin translations made in the 12th and 13th centuries. This paper analyzes this 2.1.The Nestorians process with special reference to the work done by - Abu Yahyà Sa‘id Ibn Al-Bitriq (d. circa 796- the most prominent translators. 806). He was one of the first translators from Keywords: Medieval Arabic Science, Arabian Greek into Arabic. To him it is attributed the Medicine, Scientific Knowledge in Medieval Islam, translation of Hippocrates and the best writings Transmission of Scientific Knowledge in the Middle by Galen as well as Ptolomy´s Quadripartitum. Ages, Medieval Translators - Abu Zakariya’ Yuhanna Ibn Masawayh (777- 857), a pupil of Jibril Ibn Bakhtishu’. -

Crusades 1 Crusades

Crusades 1 Crusades The Crusades were military campaigns sanctioned by the Latin Roman Catholic Church during the High Middle Ages through to the end of the Late Middle Ages. In 1095 Pope Urban II proclaimed the first crusade, with the stated goal of restoring Christian access to the holy places in and near Jerusalem. Many historians and some of those involved at the time, like Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, give equal precedence to other papal-sanctioned military campaigns undertaken for a variety of religious, economic, and political reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the The Byzantine Empire and the Sultanate of Rûm before the First Crusade Aragonese Crusade, the Reconquista, and the Northern Crusades. Following the first crusade there was an intermittent 200-year struggle for control of the Holy Land, with six more major crusades and numerous minor ones. In 1291, the conflict ended in failure with the fall of the last Christian stronghold in the Holy Land at Acre, after which Roman Catholic Europe mounted no further coherent response in the east. Some historians see the Crusades as part of a purely defensive war against the expansion of Islam in the near east, some see them as part of long-running conflict at the frontiers of Europe and others see them as confident aggressive papal led expansion attempts by Western Christendom. The Byzantines, unable to recover territory lost during the initial Muslim conquests under the expansionist Rashidun and Umayyad caliphs in the Arab–Byzantine Wars and the Byzantine–Seljuq Wars which culminated in the loss of fertile farmlands and vast grazing areas of Anatolia in 1071, after a sound victory by the occupying armies of Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Manzikert. -

Dkm080110a.Pdf

080110 DİA HAÇLILAR Richard, J. 1187, point de départ pour une nouvelle forme de la croisade .-- : The Horns of Hattīn Edit. B. Z. Kedar , pp. 250-260, Arabic literature: classical | Adab | Ethics Aerts, W. J. ; Manasses, Konstantinos A Byzantine traveller to one of the Crusader States .-- Peeters, Leuven, 2003 : East and West in the Crusader states. Context - Contacts - Confrontations. Vol. III. Acta of the congress held at Hernen Castle in September 2000. Edited by K. Ciggaar and H. Teule , pp. 165-221, Crusades & Latin Kingdoms | Byzantium | Palestine - 12th century | Travel Schulze, Ingrid; Schulze, Wolfgang; Bompaire, Marc; Northover, Peter; Metcalf, D. M. A coin hoard from the time of the First Crusade, found in the Near East, with remarks by Marc Bompaire and contributions by Peter Northover and D. Michael Metcalf .-- 2003 ISSN: 0484-8942 : Revue Numismatique, vol. 159 pp. 323-353, (2003) Madden, Thomas F. A concise history of the Crusades .-- Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, 1999 : Crusades & Latin Kingdoms | Palestine - medieval | Europe (general) - medieval 080110 / 1 Dean, B. A crusader's fortress in Palestine. A report of explorations made by the Museum, 1926 .-- 1927 DOI: 10. 2307/3255632 ISSN: 00261521 : Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, vol. 22 ii pp. 46, (1927) Museums & galleries Habashi, Hassan. A fifteenth century crusade attempt against Egypt .-- 1959 : Annals of the Faculty of Arts, Ain Shams University, vol. 5 pp. 1-18, (1959) Constable, Giles A further note on the conquest of Lisbon in 1147 .-- Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010 : The experience of Crusading. Volume one: Western approaches Edit. Marcus Bull and Norman Housley , pp. -

Aristotle's Journey to Europe: a Synthetic History of the Role Played

Aristotle’s Journey to Europe: A Synthetic History of the Role Played by the Islamic Empire in the Transmission of Western Educational Philosophy Sources from the Fall of Rome through the Medieval Period By Randall R. Cloud B.A., Point Loma Nazarene University, 1977 M.A., Point Loma University, 1979 M. Div., Nazarene Theological Seminary, 1982 Submitted to the: School of Education Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Program: Educational Policy and Leadership Concentration: Foundations of Education and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Committee: _______________________________________ Suzanne Rice, Chairperson _______________________________________ Ray Hiner _______________________________________ Jim Hillesheim _______________________________________ Marc Mahlios _______________________________________ Sally Roberts Dissertation Defended: November 6, 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Randall R. Cloud certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Aristotle’s Journey to Europe: A Synthetic History of the Role Played by the Islamic Empire in the Transmission of Western Educational Philosophy Sources from the Fall of Rome through the Medieval Period Dissertation Committee: _______________________________________ Suzanne Rice, Chairperson _______________________________________ Ray Hiner _______________________________________ Jim Hillesheim _______________________________________ -

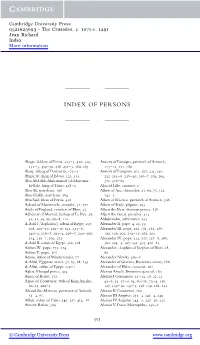

Index of Persons

Cambridge University Press 0521623693 - The Crusades, c. 1071-c. 1291 Jean Richard Index More information ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ INDEX OF PERSONS ÐÐÐÐÐÐ. ÐÐÐÐÐÐ Abaga, il-khan of Persia, 423±4, 426, 429, Aimery of Limoges, patriarch of Antioch, 432±3, 439±40, 446, 452±3, 460, 463 113±14, 171, 180 Abaq, atabeg of Damascus, 173±4 Aimery of Lusignan, 201, 207, 225, 230, Abgar, St, king of Edessa, 122, 155 232, 235±6, 238±40, 256±7, 264, 294, Abu Abdallah Muhammad (al-Mustansir 371, 376±80 bi-llah), king of Tunis, 428±9 Alan of Lille, canonist, 2 Abu Ali, merchant, 106 Albert of Aix, chronicler, 21, 69, 75, 123, Abu Ghalib, merchant, 384 142±3 Abu Said, khan of Persia, 456 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Antioch, 396 Achard of Montmerle, crusader, 31, 271 Albert of Stade, pilgrim, 293 Adela of England, countess of Blois, 35 Albert the Bear, German prince, 158 AdheÂmar of Monteil, bishop of Le Puy, 28, Albert the Great, preacher, 413 32, 42, 49, 60, 66±8, 112 Aldobrandin, adventurer, 254 al-Adil I (`Saphadin'), sultan of Egypt, 197, Alexander II, pope, 4, 23, 39 208, 209±10, 229±30, 232, 235±6, Alexander III, pope, 122, 181, 185, 188, 240±2, 256±7, 293±4, 296±7, 299±300, 190, 199, 202, 214±15, 260, 292 314, 350±1, 362, 375 Alexander IV, pope, 335, 337, 357±8, 360, al-Adil II, sultan of Egypt, 322, 328 362, 364±5, 367, 391, 397, 410±13 Adrian IV, pope, 175, 214 Alexander, chaplain of Stephen of Blois, 28, Adrian V, pope, 385 60 Adson, abbot of MontieÂrender, 17 Alexander Nevski, 360±1 al-Afdal, Egyptian vizier, 57, 65, 68, 139 Alexander of Gravina, -

Hermes, Hermeticism, and Related Eight Wikipedia Articles

Hermes, Hermeticism, and Related Eight Wikipedia Articles PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 11 May 2011 01:25:11 UTC Contents Articles Hermes 1 Hermes Trismegistus 13 Thoth 18 Hermeticism 24 Hermetica 33 Hermetic Qabalah 37 Emerald Tablet 41 Kybalion 45 References Article Sources and Contributors 50 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 52 Article Licenses License 53 Hermes 1 Hermes Hermes So-called “Logios Hermes” (Hermes,Orator). Marble, Roman copy from the late 1st century CE - early 2nd century CE after a Greek original of the 5th century BCE. Messenger of the gods God of commerce, thieves, travelers, sports, athletes, and border crossings, guide to the Underworld Abode Mount Olympus Symbol Caduceus, Talaria, Tortoise, Lyre, Rooster, Consort Merope, Aphrodite, Dryope, Peitho Parents Zeus and Maia Roman equivalent Mercury Hermes ( /ˈhɜrmiːz/; Greek Ἑρμῆς) is the great messenger of the gods in Greek mythology and a guide to the Underworld. Hermes was born on Mount Cyllene in Arcadia. An Olympian god, he is also the patron of boundaries and of the travelers who cross them, of shepherds and cowherds, of the cunning of thieves,[1] of orators and wit, of literature and poets, of athletics and sports, of weights and measures, of invention, and of commerce in general.[2] His symbols include the tortoise, the rooster, the winged sandals, the winged hat, and the caduceus. In the Roman adaptation of the Greek religion (see interpretatio romana), Hermes was identified with the Roman god Mercury, who, though inherited from the Etruscans, developed many similar characteristics, such as being the patron of commerce. -

THE PECIA SYSTEM and ITS USE Alison Joan Ray

THE PECIA SYSTEM AND ITS USE IN THE CULTURAL MILIEU OF PARIS, C1250-1330 Alison Joan Ray UCL Submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2015 1 I, Alison Joan Ray, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed, ___________________ 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is an examination of the pecia system in operation at the University of Paris from c1250 to 1330, and its use in the cultural milieu of the city during this period. An appendix (1) lists the manuscripts with user notes on which the thesis is primarily based. As the university community rose as a leading force in theology and philosophy, so too did the book trade that supported this network. The pecia system of book production mass-produced texts efficiently and at a low cost to its users, mainly university masters, students, preachers, and visitors to the Paris cultural community. Users interacted with pecia manuscripts by leaving a wide range of marginalia in works. Marginalia are classified according to a devised user typology scheme and include ownership marks, passage summaries, and comments on the main text. We have two further surviving sources for the Paris system: bookseller lists of pecia-produced works from 1275 and 1304. Chapters 1 to 10 examine separate genres of texts available on the pecia lists, theological and philosophical works as well as preaching aids. That Paris pecia manuscripts were used in action as preaching aids is one of the conclusions the user notes help to establish. -

Etk/Evk Namelist

NAMELIST Note that in the online version a search for any variant form of a name (headword and/or alternate forms) must produce all etk.txt records containing any of the forms listed. A. F. H. V., O.P. Aali filius Achemet Aaron .alt; Aaros .alt; Arez .alt; Aram .alt; Aros philosophus Aaron cum Maria Abamarvan Abbo of Fleury .alt; Abbo Floriacensis .alt; Abbo de Fleury Abbot of Saint Mark Abdala ben Zeleman .alt; Abdullah ben Zeleman Abdalla .alt; Abdullah Abdalla ibn Ali Masuphi .alt; Abdullah ibn Ali Masuphi Abel Abgadinus Abicrasar Abiosus, John Baptista .alt; Abiosus, Johannes Baptista .alt; Abiosus, Joh. Ablaudius Babilonicus Ableta filius Zael Abraam .alt; Abraham Abraam Iudeus .alt; Abraam Iudeus Hispanus .alt; Abraham Iudeus Hispanus .alt; Abraam Judeus .alt; Abraham Iudaeus Hispanus .alt; Abraham Judaeus Abracham .alt; Abraham Abraham .alt; Abraam .alt; Abracham Abraham Additor Abraham Bendeur .alt; Abraham Ibendeut .alt; Abraham Isbendeuth Abraham de Seculo .alt; Abraham, dit de Seculo Abraham Hebraeus Abraham ibn Ezra .alt; Abraham Avenezra .alt; ibn-Ezra, Avraham .alt; Aben Eyzar ? .alt; Abraham ben Ezra .alt; Abraham Avenare Abraham Iudaeus Tortuosensis Abraham of Toledo Abu Jafar Ahmed ben Yusuf ibn Kummed Abuali .alt; Albualy Abubacer .alt; Ibn-Tufail, Muhammad Ibn-Abd-al-Malik .alt; Albubather .alt; Albubather Alkasan .alt; Abu Bakr Abubather Abulhazen Acbrhannus Accanamosali .alt; Ammar al-Mausili Accursius Parmensis .alt; Accursius de Parma Accursius Pistoriensis .alt; Accursius of Pistoia .alt; M. Accursium Pistoriensem -

The Woman Translator in the Middle Ages. Selected Examples of Female Translation Activity

Przekładaniec. A Journal of Literary Translation 24 (2010): 19–30 doi:10.4467/16891864ePC.12.002.0564 JERZY STRZELCZYK THE WOMAN TRANSLATOR IN THE MIDDLE AGES. SELECTED EXAMPLES OF FEMALE TRANSLATION ACTIVITY Abstract: Translatory achievements of medieval women are rarely discussed. In antiquity, Greek and Roman writings were practically all composed in either of the two languages. Greek dominated, since Latin women’s writing did not reach sophistication, or at least we do not possess proof of it. In the early Middle Ages the situation changed: Latin became dominant, and writing in the vernacular, which included women’s writing, started to be recognized. While scholarly research tended to focus on high-brow, original literature, female literary endeavours were largely disregarded. Translation, a low-brow activity, was not considered original. Comments about it are rather infrequent in early compendia of medieval literature. This absence may be partly explained by the fact that originality itself was not held in high regard in the Middle Ages. Only recently has the growing research into social and legal conditions of early women as well as into their varied cultural and literary expressions brought them a deserved recognition. Keywords: medieval women translators, vernacular languages, paraphrase, hagiography, chivalric poetry, Secretum secretorum, fables, Fürstenspiegel, Marie de France, Clemence of Barking, Hiltgart von Hürnheim, Elisabeth von Nassau- Saarbrücken, Eleanor of Scotland, Archduchess of Austria The aim of this paper is simple: to sketch the problem of translatory in- terests and achievements of medieval women writers who belonged in the European culture. So far this topic has not been properly discussed or even noticed by historians.