Brady, Connolly & Masuda, P.C. Sixth Annual Spring Seminar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Counsel: Alden L

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civ. No. 1:07-cv-01021-PLF ) WHOLE FOODS MARKET, INC., ) REDACTED - PUBLIC VERSION ) And ) ) WILD OATS MARKETS, INC., ) ) Defendants. ) ~~~~~~~~~~~~) JOINT MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES OF WHOLE FOODS MARKET, INC., AND WILD OATS MARKETS, INC. IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Paul T. Denis (DC Bar No. 437040) Paul H. Friedman (DC Bar No. 290635) Jeffrey W. Brennan (DC Bar No. 447438) James A. Fishkin (DC Bar No. 478958) Michael Farber (DC Bar No. 449215) Rebecca Dick (DC Bar No. 463197) DECHERTLLP 1775 I Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 Telephone: (202) 261-3430 Facsimile: (202) 261-3333 Of Counsel: Alden L. Atkins (DC Bar No. 393922) Neil W. Imus (DC Bar No. 394544) Roberta Lang John D. Taurman (DC Bar No. 133942) Vice-President of Legal Affairs and General Counsel VINSON & ELKINS L.L.P. Whole Foods Market, Inc. The Willard Office Building 550 Bowie Street 1455 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Suite 600 Austin, TX Washington, DC 20004-1008 Telephone (202) 639-6500 Facsimile (202) 639-6604 Attorneys for Whole Foods Market, Inc. Clifford H. Aronson (DC Bar No. 335182) Thomas Pak (Pro Hae Vice) Matthew P. Hendrickson (Pro Hae Vice) SKADDEN, ARPS, SLATE, MEAGHER &FLOMLLP Four Times Square NewYork,NY 10036 Telephone: (212) 735-3000 [email protected] Gary A. MacDonald (DC Bar No. 418378) SKADDEN, ARPS, SLATE, MEAGHER &FlomLLP 1440 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 371-7000 [email protected] Terrence J. Walleck (Pro Hae Vice) 2224 Pacific Dr. -

Economics of Change in Market Structure, Conduct, and Performance the Baking Industry 1947-1958

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska 12-1963 Economics of Change in Market Structure, Conduct, and Performance The Baking Industry 1947-1958 Richard G. Walsh University of Nebraska - Lincoln Bert M. Evans University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Walsh, Richard G. and Evans, Bert M., "Economics of Change in Market Structure, Conduct, and Performance The Baking Industry 1947-1958" (1963). Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska). 48. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers/48 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. new series no. 28 University of Nebraska Studies december 1963 Richard G. Walsh Bert M. Evans Economics of Change in Market Structure, Conduct, and Performance The Baking Industry 1947-1958 university of nebraska studies : new series no. 28 published by the university at lincoln: december 1963 The University of Nebraska The £lard of Regents RICHARD E. ADKINS B. N. GREENBERG, M.D., president J. G. ELLIOTI JOSEPH SOSHNIK, corporation secretary VAL PETERSON CLARENCE E. SWANSON J. LEROY WELSH The Chancellor CLIFFORD M. HARDIN Richard G. Walsh Bert M. Evans Economics of Change in Market Structure, Conduct, and Performance The Baking Industry 1947-1958 university of nebraska studies : new series no. -

MSCA Newsletter

APRIL 2012 Minnesota Shopping Center Association Vol 26. No. 4 In this Issue Steel Studs Exposed ---- FEATuRE 1 Yankee Square ------- SNAPSHOT 1 Pro-Cuts ------------- RISING STAR 3 LaValle/Beazley --- MEMBER PROFILES 5 Grocery -------- PROGRAM RECAP 6 Membership Directory - MY MSCA 7 Connection Feature by Judy Lawrence , Kraus-Anderson Companies Steel Studs-Exposed! ave you noticed an increased hum of activity in your First of all, we need to come up with a plan or at least an leasing office lately? Are leasing agents starting to outline spec that a contractor can use for pricing. Once you hold their heads up higher and maybe even smiling a have the plan, you must decide who would be the Hlittle bit? These are indications that the market may be appropriate contractor to price this out for you. Make sure that loosening up and we are actually seeing some realistic you are working with a contractor that thinks like you do and deals coming across our desks. So the leasing agents have that understands your priorities and values. I am very fortunate found a perfect fit for your space, now it is time to get some in that I have four different contractors I can put in this pricing to see how we can fit the prospect into the space. category. I select the contractor based on the type and size of the project and their familiarity with the property. I then ship In my role as a construction manager, I have to look at the the spec to the contractor with a copy of the building plan. -

Food Distribution in the United States the Struggle Between Independents

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 99 JUNE, 1951 No. 8 FOOD DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES, THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN INDEPENDENTS AND CHAINS By CARL H. FULDA t I. INTRODUCTION * The late Huey Long, contending for the enactment of a statute levying an occupation or license tax upon chain stores doing business in Louisiana, exclaimed in a speech: "I would rather have thieves and gangsters than chain stores inLouisiana." 1 In 1935, a few years later, the director of the National Association of Retail Grocers submitted a statement to the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, I Associate Professor of Law, Rutgers University School of Law. J.U.D., 1931, Univ. of Freiburg, Germany; LL. B., 1938, Yale Univ. Member of the New York Bar, 1941. This study was originally prepared under the auspices of the Association of American Law Schools as one of a series of industry studies which the Association is sponsoring through its Committee on Auxiliary Business and Social Materials for use in courses on the antitrust laws. It has been separately published and copyrighted by the Association and is printed here by permission with some slight modifications. The study was undertaken at the suggestion of Professor Ralph F. Fuchs of Indiana University School of Law, chairman of the editorial group for the industry studies, to whom the writer is deeply indebted. His advice during the preparation of the study and his many suggestions for changes in the manuscript contributed greatly to the improvement of the text. Acknowledgments are also due to other members of the committee, particularly Professors Ralph S. -

June 11-14, 2011 Snow King Resort Jackson Hole, Wyoming

PROGRAM BOOK JUNE 11-14, 2011 SNOW KING RESORT JACKSON HOLE, WYOMING CHILDREN’S TUMOR FOUNDATION 95 PINE STREET, 16TH FLOOR, NEW YORK, NY 10005 | WWW.CTF.ORG | 212.344.6633 Dear NF Conference Attendees: On behalf of the Children’s Tumor Foundation, welcome to the 2011 NF Conference. Yes we are back in the mountains! Those NF ‘historians’ among us will remember that until 2006 this meeting was held at the Hotel Jerome in Aspen, Colorado. We know many of you loved that mountain setting, and recall with fondness the time when you knew everyone at the meeting personally, every afternoon was totally free, and everyone could fit onto the Jerome’s terrace for the farewell dinner. Those early meetings were special and those of you who took part were the pioneers who laid the founding stones of NF research. We outgrew the Hotel Jerome in 2007, as meeting attendance grew from 140 in 2005 to over 300 in 2010. What happened? In short, NF research progress happened. We are no longer speculating about NF clinical trials – they are underway. As of this spring, 19 NF specific trials were listed on clinicaltrials.gov. This is incredible progress. The NF Conference remains the foremost venue for world-class discussion on NF biology. But it is now also now a forum for the clinicians to discuss ongoing NF trials, and to collaborate with the scientists as to the next drugs they should consider. The meeting agenda has expanded to accommodate these new developments in our search to unlock the mysteries of NF. -

Prices and Profits of Leading Retail Food Chains, 1970-74

K76 PRICES AND PROFITS OF LEADING RETAIL FOOD CHAINS, 1970-74 HEARINGS BEFORE THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES NINETY-FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 30 AND APRIL 5, 1977 Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 96-514 WASHINGTON: 1977 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 , It. I4 JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE (Created pursuant to sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Cong.) RICHARD BOLLING, Missouri, Chairman HUBERT H. HUMPHREY, Minnesota, Vice Chairman HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SENATE HENRY S. REUSS, Wisconsin JOHN SPARKMAN, Alabama WILLIAM S. MOORHEAD, Pennsylvania WILLIAM PROXMIRE, Wisconsin LEE H. HAMILTON, Indiana ABRAHAM RIBICOFF, Connecticut GILLIS W. LONG, Louisiana LLOYD BENTSEN, Texas OTIS G. PIKE, New York EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts CLARENCE J. BROWN, Ohio JACOB K. JAVITS, New York GARRY BROWN, Michigan WILLIAM V. ROTH, JR., Delaware MARGARET M. HECKLER, Massachusetts JAMES A. McCLURE, Idaho JOHN H. ROUSSELOT, California ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah JOHN R. STARK, Executive Director Louts C. KRAUTHOFF II, Assistant Director RICHARD F. KAUFMAN, General Counsel ECONOMISTS WILLIAm R. BUECHNER KENT H. HUGHES PHILIP MCMARTIN G. THOMAS CATOR SARAH JACKSON GEORGE R. TYLER WILLIAM A. Cox JOHN R. KARLIK ROBERT D. HAMRIN L. DOUGLAS LEE MINoarIY CHARLES H. BRADFORD STEPHEN J. ENTIN GEORGE D. KRuMSHAAR, Jr. M. CATHERINE MILLER MARE R. POLICINSEI (II) -CONTENTS WITNESSES AND STATEMENTS WEDNESD-AY, MARCH 30,41977 Long, Hon. Gillis W., cochairperson, member of the Joint Economic Com- Page mittee: Opening statement - - 1 Heckler, Hon. Margaret M., cochairperson, member of the Joint Economic Committee: Opening statement--____________-__-_-_-_-__-__-_ 3 Mueller, Willard F., and Bruce W. -

Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies

FSRG Publication Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies edited by Kyle W. Stiegert and Dong Hwan Kim FSRG Publication, November 2009 FSRG Publication Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies edited by Kyle W. Stiegert Dong Hwan Kim November 2009 Kyle Stiegert [email protected] The authors thank Kate Hook for her editorial assistance. Any mistakes are those of the authors. Comments are encouraged. Food System Research Group Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Wisconsin-Madison http://www.aae.wisc.edu/fsrg/ All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this document are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. Copyright © by the authors. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for noncommercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. ii Chapter 7: Food Retailing in the United States: History, Trends, Perspectives Kyle W. Stiegert and Vardges Hovhannisyan 1. INTRODUCTION: FOOD RETAILING: 1850-1990 Before the introduction of supermarkets, fast food outlets, supercenters, and hypermarts, various other food retailing formats operated successfully in the US. During the latter half of the 19th century, the chain store began its rise to dominance as grocery retailing format. The chain grocery store began in 1859 when George Huntington Hartford and George Gilman founded The Great American Tea Company, which later came to be named The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company (Adelman, 1959). The typical chain store was 45 to 55 square meters, containing a relatively limited assortment of goods. -

Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies

FSRG Publication Structural Changes in Food Retailing: Six Country Case Studies edited by Kyle W. Stiegert Dong Hwan Kim November 2009 Kyle Stiegert [email protected] Dong Hwan Kim [email protected] The authors thank Kate Hook for her editorial assistance. Any mistakes are those of the authors. Comments are encouraged. Food System Research Group Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Wisconsin-Madison http://www.aae.wisc.edu/fsrg/ All views, interpretations, recommendations, and conclusions expressed in this document are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the supporting or cooperating organizations. Copyright © by the authors. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for noncommercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. ii Table of Contents Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 1 1. Introduction 1 2. Outline of the Book 1 3. Impact of Dominant Food Retailers: Review of Theories and Empirical Studies 3 3.1. Market Power vs. Efficiency 3 3.2. Vertical Relationship between Food retailers and Food producers: Vertical Restraints, Fees and Services Enforced by Retailers 5 Fees and Services 5 Coalescing Power 8 3.3. Market Power Studies 8 References 17 CHAPTER 2: THE CASE OF AUSTRALIA 21 1. Introduction 21 2. Structure of Food Retailing in Australia 21 2.1 Industry Definition of Food Retailing 21 2.2 Basic Structure of Retail Food Stores 22 2.3 Food Store Formats 24 2.4 Market Share and Foreign Direct Investment 25 3. Effects of Increased Food Retail Concentration on Consumers, Processors and Suppliers 28 4. -

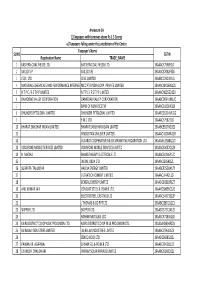

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 History of Modern Grocery Stores In

1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 History of Modern Grocery Stores in U.S.A. and Indonesia 1.1.1. The History of Modern Grocery Stores in U.S. As modern concept of grocery shopping, a self-service grocery store is the prototype of today gigantic hypermarkets, using the same principal of the self-serving experiences and organized products according to its categories, supported with sanitary of the facility and products hygiene. A self-service grocery store has evolved through decades by adding not only dry-goods (daily products with long expiration period), but also daily farm products, such as: meats, milk, fruits, vegetables, and breads to the varieties of the goods. According to the U.S. Patent #1242872 (http://patft.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?patentnumber=1242872) Piggly Wiggly is the first grocery store which implements the concept of self-serving from customers and the use of bar-code (Patent #2612994) in United States of America. The first acknowledged grocery store that operates professionally to serve customers was patented by Clarence Saunders in 1917. In the early start, one Piggly Wiggly store serves customers, majority of housewives, located in Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.A. Soon after the public found that the new way of shopping their daily needs turns out to be easier, faster, and offer wider options of dry-goods with tagged price in each item, at the end of 1930s there were over 2,600 stores across the US as the prove of stores’ success story. 2 Promising growth of Piggly Wiggly is noted as the start of the chain store explosion, especially in 1920s. -

U.S. END MARKET ANALYSIS for KENYAN TEA December 2017

U.S. END MARKET ANALYSIS FOR KENYAN TEA December 2017 DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations iv Executive Summary 5 General Market Information 6 1.1. U.S. Market Size and Projections 6 1.2. Tea Products and Market Niches 6 1.3. Competition in the Tea Market 7 1.4. Teas from Kenya and Brief Overview of the Sector 8 1.5. Purple Tea 10 1.6. Tea Tourism 11 U.S. Market Structure and Characteristics of Selected Tea Products 12 2.1. Market Size and Trends by Tea Products 12 2.2. Market Segments 12 2.3. Product Attributes 13 2.4. Prices at Key Channels and Product Origin 13 2.5. U.S. Domestic Production 14 2.6. U.S. Import Evolution by Top Countries 14 2.7. Kenyan Exports to the U.S. 16 U.S. Tariff Structure 17 3.1. Tariffs for Kenya 17 3.2. Tariffs for Third Countries 18 U.S. Non-Tariff Requirements 19 4.1. Import Regulations 19 4.2. AGOA Rules of Origin and Compliance 19 4.3. Applicable Standards and Certifications 19 4.4. Customs Procedures 20 4.5. Packaging and Labeling Requirements 20 U.S. Consumer Trends 22 5.1. Current Consumption Trends 22 5.2. Future Consumption Trends 22 U.S. Distribution 23 6.1. Origin of Imports (Key Competitors) 23 6.2. Types of Importers 25 6.3. Supplier Selection by U.S. -

About Labor Unions — Page 3 C Old C a Sh

[CJmcMD mmm) THE FOOD DEALER W lil'-W t/ hJ'^y jl iI^W [1TM1 iliJ ii UH iJ[&liW I'lil' K >/ HI '(1 mM AUG.-SEPT., 1973 Pepsi-Cola Cites Retailers The Pepsi-Cola Metropolitan Bottling-Company, recently honored some 60 food and beverage merchants at a dinner in their honor. Pictured above at the event, from left, Tom Regina, Pepsi vice-president, Jay Welch, Louis Vescio, Tom Noxon of Pepsi, and Michael Giancotti. Pepsi presented the retailers with special service citations. About Labor Unions — Page 3 C old c a sh . If you re a beer drinker, you want it ice cold. But if you re a beer seller, you want it red hot Because a red hot seller is the kind of item that makes a man a success in the beer business. In the last 4 years Stroh s sales are up over 60% . At that rate, it's one of the hottest cold beers around. From one beer lover to another. THE FOOD DEALER Aug-Sept., 1973 GUEST EDITORIAL What To Do If Union Orgonizers Come Around By EDWIN RICKER zation cards that the organizer is in authorization cards. If he does, PLRS Management Consultants asking to be signed. An authoriza he may take them to the Labor tion card is easy to get signed by Board and ask for an election which Due to the many supermarket organizers and in 90% of the cases, would be normally granted. units that are being closed by such most employees are not truly aware Most unions try to obtain more national firms as A & P, Kroger, of what significance the signing of than 50 % of the employee’s signa and National Tea, many unions in an authorization card happens to tures on cards knowing that with the retail field find themselves hav be.