Michelangelo and Allography: Expanded Authorship in Renaissance Artwork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Ruse Secluded Character Set for the Source

Mukt Shabd Journal Issn No : 2347-3150 A Ruse Secluded character set for the Source Mr. J Purna Prakash1, Assistant Professor Mr. M. Rama Raju 2, Assistant Professor Christu Jyothi Institute of Technology & Science Abstract We are rich in data, but information is poor, typically world wide web and data streams. The effective and efficient analysis of data in which is different forms becomes a challenging task. Searching for knowledge to match the exact keyword is big task in Internet such as search engine. Now a days using Unicode Transform Format (UTF) is extended to UTF-16 and UTF-32. With helps to create more special characters how we want. China has GB 18030-character set. Less number of website are using ASCII format in china, recently. While searching some keyword we are unable get the exact webpage in search engine in top place. Issues in certain we face this problem in results announcement, notifications, latest news, latest products released. Mainly on government websites are not shown in the front page. To avoid this trap from common people, we require special character set to match the exact unique keyword. Most of the keywords are encoded with the ASCII format. While searching keyword called cbse net results thousands of websites will have the common keyword as cbse net results. Matching the keyword, it is already encoded in all website as ASCII format. Most of the government websites will not offer search engine optimization. Match a unique keyword in government, banking, Institutes, Online exam purpose. Proposals is to create a character set from A to Z and a to z, for the purpose of data cleaning. -

Kiraz 2019 a Functional Approach to Garshunography

Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 7 (2019) 264–277 brill.com/ihiw A Functional Approach to Garshunography A Case Study of Syro-X and X-Syriac Writing Systems George A. Kiraz Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton and Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute, Piscataway [email protected] Abstract It is argued here that functionalism lies at the heart of garshunographic writing systems (where one language is written in a script that is sociolinguistically associated with another language). Giving historical accounts of such systems that began as early as the eighth century, it will be demonstrated that garshunographic systems grew organ- ically because of necessity and that they offered a certain degree of simplicity rather than complexity.While the paper discusses mostly Syriac-based systems, its arguments can probably be expanded to other garshunographic systems. Keywords Garshuni – garshunography – allography – writing systems It has long been suggested that cultural identity may have been the cause for the emergence of Garshuni systems. (In the strictest sense of the term, ‘Garshuni’ refers to Arabic texts written in the Syriac script but the term’s semantics were drastically extended to other systems, sometimes ones that have little to do with Syriac—for which see below.) This paper argues for an alterna- tive origin, one that is rooted in functional theory. At its most fundamental level, Garshuni—as a system—is nothing but a tool and as such it ought to be understood with respect to the function it performs. To achieve this, one must take into consideration the social contexts—plural, as there are many—under which each Garshuni system appeared. -

The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing Writing Systems Using Orthography Profiles

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Moran, Steven ; Cysouw, Michael DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-135400 Monograph The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. Originally published at: Moran, Steven; Cysouw, Michael (2017). The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles. CERN Data Centre: Zenodo. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Steven Moran & Michael Cysouw Change dedication in localmetadata.tex Preface This text is meant as a practical guide for linguists, and programmers, whowork with data in multilingual computational environments. We introduce the basic concepts needed to understand how writing systems and character encodings function, and how they work together. The intersection of the Unicode Standard and the International Phonetic Al- phabet is often not met without frustration by users. Nevertheless, thetwo standards have provided language researchers with a consistent computational architecture needed to process, publish and analyze data from many different languages. We bring to light common, but not always transparent, pitfalls that researchers face when working with Unicode and IPA. Our research uses quantitative methods to compare languages and uncover and clarify their phylogenetic relations. However, the majority of lexical data available from the world’s languages is in author- or document-specific orthogra- phies. -

A Ruse Secluded Character Set for the Source

JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURE & TECHNOLOGY Issn No : 1006-7930 A Ruse Secluded character set for the Source Mr. J Purna Prakash1, Assistant Professor Mr. M. Rama Raju 2, Assistant Professor Christu Jyothi Institute of Technology & Science Abstract We are rich in data, but information is poor, typically world wide web and data streams. The effective and efficient analysis of data in which is different forms becomes a challenging task. Searching for knowledge to match the exact keyword is big task in Internet such as search engine. Now a days using Unicode Transform Format (UTF) is extended to UTF-16 and UTF-32. With helps to create more special characters how we want. China has GB 18030-character set. Less number of website are using ASCII format in china, recently. While searching some keyword we are unable get the exact webpage in search engine in top place. Issues in certain we face this problem in results announcement, notifications, latest news, latest products released. Mainly on government websites are not shown in the front page. To avoid this trap from common people, we require special character set to match the exact unique keyword. Most of the keywords are encoded with the ASCII format. While searching keyword called cbse net results thousands of websites will have the common keyword as cbse net results. Matching the keyword, it is already encoded in all website as ASCII format. Most of the government websites will not offer search engine optimization. Match a unique keyword in government, banking, Institutes, Online exam purpose. Proposals is to create a character set from A to Z and a to z, for the purpose of data cleaning. -

Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections

Journal de la Société des Océanistes 129 | juillet-décembre 2009 Varia Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections Paul Horley Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jso/5813 DOI: 10.4000/jso.5813 ISSN: 1760-7256 Publisher Société des océanistes Printed version Date of publication: 15 December 2009 Number of pages: 249-261 ISBN: 978-2-85430-026-0 ISSN: 0300-953x Electronic reference Paul Horley, « Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections », Journal de la Société des Océanistes [Online], 129 | juillet-décembre 2009, Online since 30 December 2012, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jso/5813 ; DOI : 10.4000/jso.5813 © Tous droits réservés Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections by Paul HORLEY* ABSTRACT RÉSUMÉ Studies of three original rongorongo tablets (Tahua, L’étude menée sur trois tablettes rongorongo origina- Aruku Kurenga and Mamari) revealed clear traces of les (Tahua, Aruku Kurenga et Mamari) montre claire- two-stage carving (pre-incising with an obsidian flake ment que les signes ont été tracés au cours de deux and contour enhancement with a shark tooth). Most étapes successives : pré-incision avec un éclat d’obsi- probably, the texts were written in short fragments with dienne puis gravure des contours avec une dent de requin. shark-tooth engraving applied before passing to the next Il est probable que de courts fragments de textes étaient fragment. Additional multiple engraving sessions might écrits et gravés à l’aide d’une dent de requin avant de been performed for finished inscription, aiming to tracer le fragment de texte suivant. -

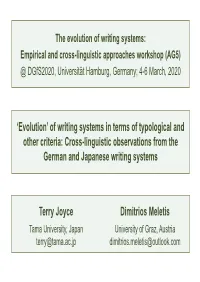

Of Writing Systems in Terms of Typological and Other Criteria: Cross-Linguistic Observations from the German and Japanese Writing Systems

The evolution of writing systems: Empirical and cross-linguistic approaches workshop (AG5) @ DGfS2020, Universität Hamburg, Germany; 4-6 March, 2020 ‘Evolution’ of writing systems in terms of typological and other criteria: Cross-linguistic observations from the German and Japanese writing systems Terry Joyce Dimitrios Meletis Tama University, Japan University of Graz, Austria [email protected] [email protected] Overview Opening remarks Selective sample of writing system (WS) typologies Alternative criteria for evaluating WSs Observations from German (GWS) + Japanese (JWS) Closing remarks Opening remarks 1: Chaos over basic terminology! Erring towards understatement, Gnanadesikan (2017: 15) notes, [t]here is, in general, significant variation in the basic terminology used in the study of writing systems. Indeed, as Meletis (2018: 73) observes regarding the differences between the concepts of WS and orthography, [t]hese terms are often shockingly misused as synonyms, or writing system is not used at all and orthography is employed instead. Similarly, Joyce and Masuda (in press) seek to differentiate between the elusive trinity of terms at heart of WS research; namely, script, WS, and orthography, with particular reference to the JWS. Opening remarks 2: Our working definitions WS1 [Schrifttyp]: Abstract relations (i.e., morphographic, syllabographic, + phonemic), as focus of typologies. WS2 [Schriftsystem]: Common usage for signs + conventions of given language, such as GWS + JWS. Script [Schrift]: Set of material signs for specific language. Orthography [Orthographie]: Mediation between script + WS, but often with prescriptive connotations of correct writing. Graphematic representation: Emerging from grapholinguistic approach, a neutral (ego preferable) alternative to orthography. GWS: Use of extended alphabetic set, as used to represent written German language. -

Simplified Lambda in an English Novel

The Quest for Information Retrieval THE QUEST FOR INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: AN INSCRIBED RELIC FROM ANCIENT RAPA NUI (EASTER ISLAND) – Part I. Tomi S. MELKA (Las Palmas de G.C., Spain) [email protected] Robert M. SCHOCH (Boston, Massachusetts, USA) [email protected] This article focuses on an antique wooden fragment from Easter Island engraved with a single rongorongo (RR) glyph. Based on our analysis, we conclude that the most likely hypothesis regarding this fragment is that it dates to pre-missionary times (prior to 1864) and was part of some type of weapon or fighting instrument, either of a functional or ritual nature. It may represent a portion of a handle for an obsidian-tipped spear or knife. The “bird”-like RR glyph on the fragment belongs in all probability to a category that has previously been connected in the scholarly literature on RR with “slumber”, and hence “waning”, “demise”, and “death”. Its presence on a hand-weapon or ceremonial warlike artifact suggests a meaningful real-world, “non-literary”, context for this glyph. Keywords: “bird”-like motif, glyph of the /600/-class, “Lutz–Terasaki fragment”, mako‘i (Thespesia populnea), mata‘a, patina, pre-missionary era, Rapa Nui (Easter Island), rongorongo script “El desorden y el esparcimiento en que se encuentran los más importantes documentos originales de la cultura pascuense, permite sospechar que en algunos museos y colecciones particulares se encuentren algunas otras piezas auténticas” [The chaos and dispersal in which the most important original documents (= rongorongo artifacts; our note) of Rapanui culture are found, allows us to suspect that a few other authentic pieces may be encountered in some museums and particular collections]. -

Can a Logographic Script Be Simplified? Lessons from the 20Th Century Chinese Writing Reform Informed by Recent Psycholinguistic Research*

Can a Logographic Script be Simplified? Lessons from the 20th Century Chinese Writing Reform Informed by Recent Psycholinguistic Research* Zev Handel University of Washington, Seattle In the 1950s and 1960s, the government of the People’s Republic of China undertook, in two stages, a carefully planned “simplification” of the logographic Chinese script. Drawing on a variety of historical precedents, over 2,000 individual graphs were modified in an attempt to make the script easier to learn and use. This was the first significant change in the official form of the Chinese script in nearly two millennia, and resulted in the script variety that is widely used today in mainland China, commonly termed “simplified Chinese characters.” Drawing on recent psycholinguistic experiments that attempt to characterize the cognitive functions involved in Chinese script processing, this study revisits long-standing questions about the efficacy of character simplification and provides some additional theoretical insights into the nature of logographic writing. The central conclusion of this study is that meaningful simplification of a logographic script is possible, but that today’s simplified character script cannot be characterized as an effective reform by any reasonable metric—it is only “simpler” in the crudest of senses. After evaluating the results of recent studies on the cognitive processing of Chinese characters, I introduce the concept of semantic orthographic depth and argue that a true simplification of a logographic script should be based on regularization of semantic and phonetic components, rather than on reduction of the number of graphs or the reduction of the number of strokes per graph. -

Transmission of the First Alphabets

Scripts in Contact: Transmission of the First Alphabets Sveva Elti di Rodeano Abstract. The alphabet is a type of notation which breaks language into small units, attempting to represent its phonological and/or phonetic repertoire. Given that writing is a way of thinking, based on a cognitive activity that re- quires mental procedures, the aim of this paper is to propose the architecture of the spelling process, described in cognitive and psycholinguistic studies, as a model for the transmission of the alphabet(s). For this purpose, the reflection is focused on the so-called first alphabets in writing systems’ history, i.e., Greek, Anatolian, Italic, and Iberian alphabets, in- troducing the new linguistic and archeological approaches which allow an earlier date and a less decisive role for the Greeks in the alphabets’ introduction. Ancient literatures’ evidence about the teaching of writing and reading are found to match with the current results of cognitive studies about the dynamics of oral reproduction, word recognition, and written reproduction. The pecu- liarities of Asia minor alphabets, which are still unsolved, will be addressed and framed within the spelling process model. 1. Introduction Currently, the alphabet is more widespread than any other system of written language. In company with Chinese characters, the alphabet provides the forms by which all living languages are written: whether Arabic, Bengali, Cyrillic, Devanagari, Greek, Hebrew, Javanese, Latin, or Tibetan or any This paper has been written as contribution to the GC21 Conference, held online due to COVID-19 pandemic. I must thanks all the participants for their direct and undirect contributions for my research, with special regards to Daniel Harbour, Hany Rashwan and Amalia Gnanadesikan. -

Proposed Additions to the Runic Range, L2/09-312 2

Proposed additions to the Runic Range 16A0-16F0 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS 1 FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 10646TP PT Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html UTH for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.htmlUTH. See also HTUhttp://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html UTH for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Proposed additions to the Runic Range, L2/09-312 2. Requester's name: Małgorzata Deroń 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual 4. Submission date: Oct. 29, 2009 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): prof. dr hab. Jacek Fisiak, prof. dr hab. Marcin Krygier 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: Yes (or) More information will be provided later: B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: Yes Name of the existing block: Runic Range 16A0-16F0 [Combining Diacritical Marks Supplement 1DC0-1DFF] 2. Number of characters in proposal: variable: 7 + (1) + 16/[12 + 1] see: 2. Justification (ii) & 4. Description 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) C-Major extinct X D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. -

Universal Penman Rollerball Nib the J-Form Dip Pen Allography Cursive

eraser An eraser or rubber is an article of stationery that is used for removing pencil and sometimes pen writings. Erasers have a rubbery consistency and are often white or pink, although modern materials allow them to be made in any cursive allography colour. Many pencils are equipped with an eraser on one Cursive is any style end. Typical erasers are made from synthetic rubber, but The letter a is depicted of handwriting that is dip pen more expensive or specialized erasers can also contain vi- fountain pen with two common glyphs nyl, plastic, or gum-like materials. Other, cheaper erasers ballpoint designed for writing A dip or nib pen consists of a metal nib A fountain pen is a nib pen that, unlike its predecessor the dip pen, contains an internal reservoir which differ between can be made out of synthetic soy-based gum. notes and letters quickly with capillary channels mounted on a of water-based liquid ink. From the reservoir, the ink is drawn through a feed to the nib and then typefaces and handwrit- A ballpoint pen has an internal chamber filled with a vis- by hand. In the Arabic, to the paper via a combination of gravity and capillary action. As a result, the typical fountain pen ing styles. Allography cous ink that is dispensed at tip during use by the rolling handle or holder, often made of wood. Latin, and Cyrillic writing Other materials can be used for the requires little or no pressure to write. is this variation in how action of a small metal sphere made of brass, steel or systems, the letters in letters are formed. -

Garshunography: Terminology and Some Formal Properties of Writing One Language in the Script of Another

GARSHUNOGRAPHY: TERMINOLOGY AND SOME FORMAL PROPERTIES OF WRITING ONE LANGUAGE IN THE SCRIPT OF ANOTHER George A. KIRAZ The sociolinguistic phenomenon of using the script of one language to write utterances of another language which already has a script of its own lacks a linguistic technical term. (This is not to be confused with the act of writing a text in one language and reading it in another for which the term alloglottography, coined by Ilya Gershevitch,1 already exists.) While the paper does not assume an intrinsic formal correlation between lan- guage and script, it does assume that there is a sociolinguistic association between them; e.g., people associate the Arabic script with the Arabic language, and the Hebrew script with the Hebrew language. The phenom- enon at hand occurs when a community makes a deliberate choice, for whatever reason, to write a language that it perceives not to be its own (although it might technically be its native tongue) in a script that it per- ceives to be its own; e.g., writing Arabic in the Hebrew script, tradition- ally called Judeo-Arabic.2 It is this phenomenon for which this paper seeks to find a technical term. As a point of departure, three plausible terms are considered but are deemed inappropriate as they have their own technical sense in literature on writing systems that differs from that required here. These terms are allography, transliteration, and heterography. 1. Allography The term allography is tempting and indeed has been considered for this purpose.3 After all, the prefix allo- gives the meaning of variation or 1 I.