Garshunography: Terminology and Some Formal Properties of Writing One Language in the Script of Another

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Different Dialects of Arabic Language

e-ISSN : 2347 - 9671, p- ISSN : 2349 - 0187 EPRA International Journal of Economic and Business Review Vol - 3, Issue- 9, September 2015 Inno Space (SJIF) Impact Factor : 4.618(Morocco) ISI Impact Factor : 1.259 (Dubai, UAE) DIFFERENT DIALECTS OF ARABIC LANGUAGE ABSTRACT ifferent dialects of Arabic language have been an Dattraction of students of linguistics. Many studies have 1 Ali Akbar.P been done in this regard. Arabic language is one of the fastest growing languages in the world. It is the mother tongue of 420 million in people 1 Research scholar, across the world. And it is the official language of 23 countries spread Department of Arabic, over Asia and Africa. Arabic has gained the status of world languages Farook College, recognized by the UN. The economic significance of the region where Calicut, Kerala, Arabic is being spoken makes the language more acceptable in the India world political and economical arena. The geopolitical significance of the region and its language cannot be ignored by the economic super powers and political stakeholders. KEY WORDS: Arabic, Dialect, Moroccan, Egyptian, Gulf, Kabael, world economy, super powers INTRODUCTION DISCUSSION The importance of Arabic language has been Within the non-Gulf Arabic varieties, the largest multiplied with the emergence of globalization process in difference is between the non-Egyptian North African the nineties of the last century thank to the oil reservoirs dialects and the others. Moroccan Arabic in particular is in the region, because petrol plays an important role in nearly incomprehensible to Arabic speakers east of Algeria. propelling world economy and politics. -

A Ruse Secluded Character Set for the Source

Mukt Shabd Journal Issn No : 2347-3150 A Ruse Secluded character set for the Source Mr. J Purna Prakash1, Assistant Professor Mr. M. Rama Raju 2, Assistant Professor Christu Jyothi Institute of Technology & Science Abstract We are rich in data, but information is poor, typically world wide web and data streams. The effective and efficient analysis of data in which is different forms becomes a challenging task. Searching for knowledge to match the exact keyword is big task in Internet such as search engine. Now a days using Unicode Transform Format (UTF) is extended to UTF-16 and UTF-32. With helps to create more special characters how we want. China has GB 18030-character set. Less number of website are using ASCII format in china, recently. While searching some keyword we are unable get the exact webpage in search engine in top place. Issues in certain we face this problem in results announcement, notifications, latest news, latest products released. Mainly on government websites are not shown in the front page. To avoid this trap from common people, we require special character set to match the exact unique keyword. Most of the keywords are encoded with the ASCII format. While searching keyword called cbse net results thousands of websites will have the common keyword as cbse net results. Matching the keyword, it is already encoded in all website as ASCII format. Most of the government websites will not offer search engine optimization. Match a unique keyword in government, banking, Institutes, Online exam purpose. Proposals is to create a character set from A to Z and a to z, for the purpose of data cleaning. -

Kiraz 2019 a Functional Approach to Garshunography

Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 7 (2019) 264–277 brill.com/ihiw A Functional Approach to Garshunography A Case Study of Syro-X and X-Syriac Writing Systems George A. Kiraz Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton and Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute, Piscataway [email protected] Abstract It is argued here that functionalism lies at the heart of garshunographic writing systems (where one language is written in a script that is sociolinguistically associated with another language). Giving historical accounts of such systems that began as early as the eighth century, it will be demonstrated that garshunographic systems grew organ- ically because of necessity and that they offered a certain degree of simplicity rather than complexity.While the paper discusses mostly Syriac-based systems, its arguments can probably be expanded to other garshunographic systems. Keywords Garshuni – garshunography – allography – writing systems It has long been suggested that cultural identity may have been the cause for the emergence of Garshuni systems. (In the strictest sense of the term, ‘Garshuni’ refers to Arabic texts written in the Syriac script but the term’s semantics were drastically extended to other systems, sometimes ones that have little to do with Syriac—for which see below.) This paper argues for an alterna- tive origin, one that is rooted in functional theory. At its most fundamental level, Garshuni—as a system—is nothing but a tool and as such it ought to be understood with respect to the function it performs. To achieve this, one must take into consideration the social contexts—plural, as there are many—under which each Garshuni system appeared. -

The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing Writing Systems Using Orthography Profiles

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Moran, Steven ; Cysouw, Michael DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-135400 Monograph The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. Originally published at: Moran, Steven; Cysouw, Michael (2017). The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles. CERN Data Centre: Zenodo. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Steven Moran & Michael Cysouw Change dedication in localmetadata.tex Preface This text is meant as a practical guide for linguists, and programmers, whowork with data in multilingual computational environments. We introduce the basic concepts needed to understand how writing systems and character encodings function, and how they work together. The intersection of the Unicode Standard and the International Phonetic Al- phabet is often not met without frustration by users. Nevertheless, thetwo standards have provided language researchers with a consistent computational architecture needed to process, publish and analyze data from many different languages. We bring to light common, but not always transparent, pitfalls that researchers face when working with Unicode and IPA. Our research uses quantitative methods to compare languages and uncover and clarify their phylogenetic relations. However, the majority of lexical data available from the world’s languages is in author- or document-specific orthogra- phies. -

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

A Ruse Secluded Character Set for the Source

JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURE & TECHNOLOGY Issn No : 1006-7930 A Ruse Secluded character set for the Source Mr. J Purna Prakash1, Assistant Professor Mr. M. Rama Raju 2, Assistant Professor Christu Jyothi Institute of Technology & Science Abstract We are rich in data, but information is poor, typically world wide web and data streams. The effective and efficient analysis of data in which is different forms becomes a challenging task. Searching for knowledge to match the exact keyword is big task in Internet such as search engine. Now a days using Unicode Transform Format (UTF) is extended to UTF-16 and UTF-32. With helps to create more special characters how we want. China has GB 18030-character set. Less number of website are using ASCII format in china, recently. While searching some keyword we are unable get the exact webpage in search engine in top place. Issues in certain we face this problem in results announcement, notifications, latest news, latest products released. Mainly on government websites are not shown in the front page. To avoid this trap from common people, we require special character set to match the exact unique keyword. Most of the keywords are encoded with the ASCII format. While searching keyword called cbse net results thousands of websites will have the common keyword as cbse net results. Matching the keyword, it is already encoded in all website as ASCII format. Most of the government websites will not offer search engine optimization. Match a unique keyword in government, banking, Institutes, Online exam purpose. Proposals is to create a character set from A to Z and a to z, for the purpose of data cleaning. -

FOLIA ORIENTALIA Arabic Dialects of Central Asia...Pdf

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK - ODDZIAL W KRAKOWIE KOMISJA ORIENTALISTYCZNA STUDIA ANDREAE ZABORSKI DEDICATA FOLIA ORIENTALIA VOL. XLIX 2012 Editorial Bond: Jerzy Anna Krasnowolska, Tomasz Ewa Siemieniec-Gob~, Lidia Joachim Editor of the Volume: Tomasz Polanski ofMainz) Mehmet (Yllchz Teknik Universitesi, Karin Preisendanz of Prochazka (University Thomas of British Desktop Publisher: Ewa >I< © Copyright jor 2012 The of this vol ume has been by the Polish Academy * This joumal can be either bought or for scholarly publications, I orders and exchange should be <l'1rII-C'>~cpri to Orientalia" ofSciences 31-018 Krak6w, Poland ISSN 0015-5675 CONTENTS Tomasz POLANSKI Introduction ... .. .... .. .. ............ .... ............... II Prof. dr hab . Andrzej ZABORSKI • Selected bibliography 1962-2012 ...... ...... .. .. .. ................... 13 Articles Mahmut AGBAHT, Werner ARNOLD Der Kluge und del' NaIT. ........... .. ...... ....... ... 25 Sergio BALOl Arabic Loans in East African Languages through Swahili: A Survey ........ .... 37 Jerzy BANCZEROWSKI, Szymon GRZELAK Translational quandaries and suggestions ....... .. .. .. ... .......... .. .... 53 Anna BELOVA Vestiges du vocalisme radical en seillitique .... ........ ................... 69 Vaclav BLAZEK A little moon-light on Afroasiatic "night" ..................... ............ 77 Francis BREYER Das Wort ftir »Konig« im aksumitischen Altathiopisch Spurensuche in einem gesprochen - und geschriebensprachlich Illultilingualen Areal ...... ... 87 Salem CHAKER Berbere et AFRO-ASIATIQUE: Reftexions du -

Book Review: Izre'el, Shlomo and Rina Drory Israel, Eds. Israel Oriental Studies Xli': Language and Culture in the Near East

Prof. Scott B. Noegel Chair, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization University of Washington Book review: Izre'el, Shlomo and Rina Drory Israel, eds. Israel Oriental Studies XlI': Language and Culture in the Near East. Leiden: E.). Brill, 1995. First Published in: Anthropological Linguistics 39/1 (1997), 175-180. 1997 BOOK REVIEWS 175 some other Arabian dialects. in Central Asian Arabic. and in some Saharan dialects ' ' .. ." (p. 50)? For those nonspecialists simply interested in Najdi Arabic, this information is irrelevant, or if this feature is relevant for them, then many other peculiarities of the dialect should have been similarly pointed out on this comparative basis; meanwhile, the specialist will note the descriptive fact and use it for his or her own purposes and prob- ably does not need the special prompting. This is true for Classical Arabic because references to Classical Arabic implicitly presuppose a diachronic model that needs to be justified on its own merits. For example, Ingham (p. 13) points out that in contrast to Classical Arabic, the glottal stop has dis- appeared in Najdi Arabic. It may be asked, however, whether this formulation correctly recapitulates the diachronic development. Apart trom a few attestations in Yemen, there are no dialects anywhere that have a glottal stop etymological with the glottal stop of Classical Arabic. This fact alone suggests that at the time of the Arabic diaspora (ca. 650 A.D.) there already existed glottal-stop-Iess dialects spread in all directions from the Arabian peninsula. Furthermore, it is well attested, both in the works of the earliest Arabic grammarians and in early Arabic orthography (including Koranic orthography), that there were early varieties of Arabic that did not have the glottal stop. -

Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections

Journal de la Société des Océanistes 129 | juillet-décembre 2009 Varia Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections Paul Horley Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jso/5813 DOI: 10.4000/jso.5813 ISSN: 1760-7256 Publisher Société des océanistes Printed version Date of publication: 15 December 2009 Number of pages: 249-261 ISBN: 978-2-85430-026-0 ISSN: 0300-953x Electronic reference Paul Horley, « Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections », Journal de la Société des Océanistes [Online], 129 | juillet-décembre 2009, Online since 30 December 2012, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/jso/5813 ; DOI : 10.4000/jso.5813 © Tous droits réservés Rongorongo Script: Carving Techniques and Scribal Corrections by Paul HORLEY* ABSTRACT RÉSUMÉ Studies of three original rongorongo tablets (Tahua, L’étude menée sur trois tablettes rongorongo origina- Aruku Kurenga and Mamari) revealed clear traces of les (Tahua, Aruku Kurenga et Mamari) montre claire- two-stage carving (pre-incising with an obsidian flake ment que les signes ont été tracés au cours de deux and contour enhancement with a shark tooth). Most étapes successives : pré-incision avec un éclat d’obsi- probably, the texts were written in short fragments with dienne puis gravure des contours avec une dent de requin. shark-tooth engraving applied before passing to the next Il est probable que de courts fragments de textes étaient fragment. Additional multiple engraving sessions might écrits et gravés à l’aide d’une dent de requin avant de been performed for finished inscription, aiming to tracer le fragment de texte suivant. -

Peripheral Arabic Dialects

University of Bucharest Center for Arab Studies ROMANO-ARABICA VI-VII 2006-2007 Peripheral Arabic Dialects UNIVERSITY OF BUCHAREST CENTER FOR ARAB STUDIES ROMANO-ARABICA New Series No 6-7 Peripheral Arabic Dialects EDITURA UNIVERSITĂŢII DIN BUCUREŞTI – 2006/2007 Editor: Nadia Anghelescu Associate Editor: George Grigore Advisory Board: Ramzi Baalbaki (Beirut) Michael G. Carter (Sidney) Jean-Patrick Guillaume (Paris) Hilary Kilpatrick (Lausanne) Chokri Mabkhout (Tunis) Yordan Peev (Sofia) Stephan Procházka (Vienna) André Roman (Lyon) Editor in Charge of the Issue: George Grigore (e-mail: [email protected]) Published by: © Center for Arab Studies Pitar Moş Street no 11, Sector 2, 70012 Bucharest, Romania Phone/fax: 0040-21-2123446 © Editura Universităţii din Bucureşti Şos. Panduri, 90-92, Bucureşti – 050663; Telefon/Fax: 0040-21-410.23.84 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.editura.unibuc.ro ISSN 1582-6953 Contents Werner Arnold, The Arabic Dialect of the Jews of Iskenderun……………………. 7 Andrei A. Avram, Romanian Pidgin Arabic............................................................... 13 Guram Chikovani, Some Peculiarities of Central Asian Arabic From the Perspective of History of Arabic Language…………………………………………. 29 Dénes Gazsi, Shi‗ite Panegyrical Poems from the Township of Dašt-i Āzādagān (H~ūzistān)..................................................................................................................... 39 George Grigore, L‘énoncé non verbal dans l‘arabe parlé à Mardin……………… 51 Otto Jastrow, Where do we stand in the -

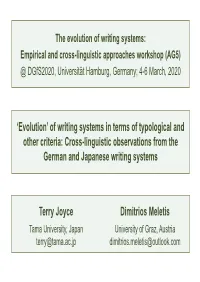

Of Writing Systems in Terms of Typological and Other Criteria: Cross-Linguistic Observations from the German and Japanese Writing Systems

The evolution of writing systems: Empirical and cross-linguistic approaches workshop (AG5) @ DGfS2020, Universität Hamburg, Germany; 4-6 March, 2020 ‘Evolution’ of writing systems in terms of typological and other criteria: Cross-linguistic observations from the German and Japanese writing systems Terry Joyce Dimitrios Meletis Tama University, Japan University of Graz, Austria [email protected] [email protected] Overview Opening remarks Selective sample of writing system (WS) typologies Alternative criteria for evaluating WSs Observations from German (GWS) + Japanese (JWS) Closing remarks Opening remarks 1: Chaos over basic terminology! Erring towards understatement, Gnanadesikan (2017: 15) notes, [t]here is, in general, significant variation in the basic terminology used in the study of writing systems. Indeed, as Meletis (2018: 73) observes regarding the differences between the concepts of WS and orthography, [t]hese terms are often shockingly misused as synonyms, or writing system is not used at all and orthography is employed instead. Similarly, Joyce and Masuda (in press) seek to differentiate between the elusive trinity of terms at heart of WS research; namely, script, WS, and orthography, with particular reference to the JWS. Opening remarks 2: Our working definitions WS1 [Schrifttyp]: Abstract relations (i.e., morphographic, syllabographic, + phonemic), as focus of typologies. WS2 [Schriftsystem]: Common usage for signs + conventions of given language, such as GWS + JWS. Script [Schrift]: Set of material signs for specific language. Orthography [Orthographie]: Mediation between script + WS, but often with prescriptive connotations of correct writing. Graphematic representation: Emerging from grapholinguistic approach, a neutral (ego preferable) alternative to orthography. GWS: Use of extended alphabetic set, as used to represent written German language. -

403 Recovering the Role of Christians in the History of the Middle East: a Workshop at Princeton University May 6-7, 2016 On

CONFERENCE REPORTS Recovering the Role of Christians in the History of the Middle East: A Workshop at Princeton University May 6-7, 2016 MICHAEL REYNOLDS, JACK TANNOUS, AND CHRISTIAN SAHNER WORKSHOP ORGANIZERS On May 6-7, 2016, the Near East and the World Seminar welcomed fourteen distinguished scholars to Princeton University to discuss the place of Christians in Middle Eastern history and historiography. At the outset, speakers were invited to reflect on how the field of Middle Eastern history generally and their work specifically changes when they consider perspectives provided by Christian sources, institutions, and individuals. A working premise of the conference was that although Christians have formed a significant portion of the population of the Middle East since the Arab conquests, the stubborn but understandable tendency of historians to conceive of the Middle East as a Muslim region has had the effect of marginalizing Christian experiences. The result has been to consign Middle Eastern Christianity to a niche specialty alongside larger fields, such as Islamic studies, Byzantine studies, church history, Jewish studies, and Ottoman history. The workshop participants answered the question of how to integrate Christians into Middle Eastern history in different ways. Robert Hoyland and Bruce Masters stressed how scholars must be open to evidence produced by Muslims and non-Muslims when writing the social and political history of the region: a source is a source, no matter its confessional origins. John-Paul Ghobrial and Bernard Heyberger underlined the importance and payoff of integrating Christians into bigger narratives about early modernity, especially how Eastern Christians served as cultural brokers between the Middle East, Europe, and the New World.