Reintroduction of Historically Extirpated Taxa on the California Channel Islands Scott A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

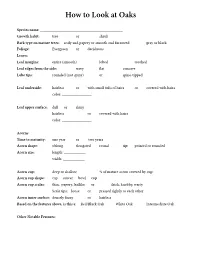

How to Look at Oaks

How to Look at Oaks Species name: __________________________________________ Growth habit: tree or shrub Bark type on mature trees: scaly and papery or smooth and furrowed gray or black Foliage: Evergreen or deciduous Leaves Leaf margins: entire (smooth) lobed toothed Leaf edges from the side: wavy fat concave Lobe tips: rounded (not spiny) or spine-tipped Leaf underside: hairless or with small tufs of hairs or covered with hairs color: _______________ Leaf upper surface: dull or shiny hairless or covered with hairs color: _______________ Acorns Time to maturity: one year or two years Acorn shape: oblong elongated round tip: pointed or rounded Acorn size: length: ___________ width: ___________ Acorn cup: deep or shallow % of mature acorn covered by cup: Acorn cup shape: cap saucer bowl cup Acorn cup scales: thin, papery, leafike or thick, knobby, warty Scale tips: loose or pressed tightly to each other Acorn inner surface: densely fuzzy or hairless Based on the features above, is this a: Red/Black Oak White Oak Intermediate Oak Other Notable Features: Characteristics and Taxonomy of Quercus in California Genus Quercus = ~400-600 species Original publication: Linnaeus, Species Plantarum 2: 994. 1753 Sections in the subgenus Quercus: Red Oaks or Black Oaks 1. Foliage evergreen or deciduous (Quercus section Lobatae syn. 2. Mature bark gray to dark brown or black, smooth or Erythrobalanus) deeply furrowed, not scaly or papery ~195 species 3. Leaf blade lobes with bristles 4. Acorn requiring 2 seasons to mature (except Q. Example native species: agrifolia) kelloggii, agrifolia, wislizeni, parvula 5. Cup scales fattened, never knobby or warty, never var. -

Birds on San Clemente Island, As Part of Our Work Toward the Recovery of the Island’S Endangered Species

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 36, Number 3, 2005 THE BIRDS OF SAN CLEMENTE ISLAND BRIAN L. SULLIVAN, PRBO Conservation Science, 4990 Shoreline Hwy., Stinson Beach, California 94970-9701 (current address: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd., Ithaca, New York 14850) ERIC L. KERSHNER, Institute for Wildlife Studies, 2515 Camino del Rio South, Suite 334, San Diego, California 92108 With contributing authors JONATHAN J. DUNN, ROBB S. A. KALER, SUELLEN LYNN, NICOLE M. MUNKWITZ, and JONATHAN H. PLISSNER ABSTRACT: From 1992 to 2004, we observed birds on San Clemente Island, as part of our work toward the recovery of the island’s endangered species. We increased the island’s bird list to 317 species, by recording many additional vagrants and seabirds. The list includes 20 regular extant breeding species, 6 species extirpated as breeders, 5 nonnative introduced species, and 9 sporadic or newly colonizing breeding species. For decades San Clemente Island had been ravaged by overgrazing, especially by goats, which were removed completely in 1993. Since then, the island’s vegetation has begun recovering, and the island’s avifauna will likely change again as a result. We document here the status of that avifauna during this transitional period of re- growth, between the island’s being largely denuded of vegetation and a more natural state. It is still too early to evaluate the effects of the vegetation’s still partial recovery on birds, but the beginnings of recovery may have enabled the recent colonization of small numbers of Grasshopper Sparrows and Lazuli Buntings. Sponsored by the U. S. Navy, efforts to restore the island’s endangered species continue—among birds these are the Loggerhead Shrike and Sage Sparrow. -

Santa Catalina Island1

Oak Restoration Trials: Santa Catalina 1 Island Lisa Stratton2 Two restoration trials involving four oak species have been implemented as part of a larger restoration program for Catalina Island. In 1997 the Catalina Island Conservancy began an active program of restoration after 50 years of ranching and farming activities on the island. The restoration program includes removing feral goats and pigs island-wide and converting 80 acres of old hayfields in Middle Canyon to native plant communities. This conversion presented the opportunity to implement experimental restoration trials to test the efficiency and efficacy of a variety of restoration techniques. The primary challenges to restoration in these areas include bison disturbance, deer browsing, long dry seasons and disturbed, weed saturated soils (e.g., Avena fatua, Cynodon dactylon (Bermuda grass), Phalaris aquatica (Harding grass) and incipient populations of Foeniculum vulgare (fennel) and Nicotiana glauca (tree tobacco). In 1999, an island scrub oak seedling trial (Quercus pacifica) was initiated to compare three different watering treatments: 1) a commercial time-release product, Driwater, 2) monthly deep-pipe watering and, 3) unwatered controls. This trial is also a factorial design that includes a native soil component. Soil from beneath mature oaks, potentially containing spore from the oak ectomycorrhizal associate, was added to half the holes at planting time. After two years the seedlings receiving the monthly watering supplements in the deep pipes were significantly taller (p<0.001) than either the no water or Driwater product treatments (45 inches vs. 33 and 29 respectively). Survivorship was higher for the deep pipe treatment (98 percent vs. -

The Conservation and Restoration of the Mexican Islands, a Successful Comprehensive and Collaborative Approach Relevant for Global Biodiversity

Chapter 9 The Conservation and Restoration of the Mexican Islands, a Successful Comprehensive and Collaborative Approach Relevant for Global Biodiversity Alfonso Aguirre-Muñoz, Yuliana Bedolla-Guzmán, Julio Hernández- Montoya, Mariam Latofski-Robles, Luciana Luna-Mendoza, Federico Méndez-Sánchez, Antonio Ortiz-Alcaraz, Evaristo Rojas-Mayoral, and Araceli Samaniego-Herrera Abstract Islands are biodiversity hotspots that offer unique opportunities for applied restoration techniques that have proven to bring inspiring outcomes. The trajectory of island restoration in Mexico is full of positive results that include (1) the removal of 60 invasive mammal populations from 39 islands, (2) the identifica- tion of conservation and restoration priorities, (3) the active restoration of seabird breeding colonies through avant-garde social attraction techniques, (4) the active restoration of integrated plant communities focusing on a landscape level, (5) applied research and science-based decision-making for the management of inva- sive alien species, (6) the legal protection of all Mexican islands, and (7) biosecurity and environmental learning programs to ensure outcomes are long lasting. Still, there are many complex challenges to face in order to achieve the goal of having all Mexican islands free of invasive mammals by 2030. Keywords Islands · Mexico · Restoration · Eradication · Biosecurity · Seabirds A. Aguirre-Muñoz · Y. Bedolla-Guzmán · J. Hernández-Montoya M. Latofski-Robles · L. Luna-Mendoza · F. Méndez-Sánchez (*) A. Ortiz-Alcaraz · E. Rojas-Mayoral · A. Samaniego-Herrera Grupo de Ecología y Conservación de Islas, A. C, Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 177 A. -

SF Street Tree Species List 2019

Department of Public Works 2019 Recommended Street Tree Species List 1 Introduction The San Francisco Urban Forestry Council periodically reviews and updates this list of trees in collaboration with public and non-profit urban forestry stakeholders, including San Francisco Public Works, Bureau of Urban Forestry and Friends of the Urban Forest. The 2019 Street Tree List was approved by the Urban Forestry Council on October 22, 2019. This list is intended to be used for the public realm of streets and associated spaces and plazas that are generally under the jurisdiction of the Public Works. While the focus is on the streetscape, e.g., tree wells in the public sidewalks, the list makes accommodations for these other areas in the public realm, e.g., “Street Parks.” While this list recommends species that are known to do well in many locations in San Francisco, no tree is perfect for every potential tree planting location. This list should be used as a guideline for choosing which street tree to plant but should not be used without the help of an arborist or other tree professional. All street trees must be approved by Public Works before planting. Sections 1 and 2 of the list are focused on trees appropriate for sidewalk tree wells, and Section 3 is intended as a list of trees that have limited use cases and/or are being considered as street trees. Finally, new this year, Section 4, is intended to be a list of local native tree and arborescent shrub species that would be appropriate for those sites in the public realm that have more space than the sidewalk planting wells, for example, stairways, “Street Parks,” plazas, and sidewalk gardens, where more concrete has been extracted. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization. -

General Management Plan 1980 Volume 2

general management plan volume 2 natural / cultural resource management september 1980 . ---·-- -- --- -------,---·--·-----···--- - - -· ·_~_ •·.• .. -•,·· ''( ... ::: ' .. _:.;~~!5'~ ' ' ,,' / .... - ., .:._ :_::.~.":_~~:~_~;~ I i...r.. / f·i' 1: CHANN L I ' -'rt~:;! '·'.l\tJACAPA'.'SANTAJl!i~,;~~,- NATIONAL PARK / CALIFORNIA RECOMMENDED: Kenneth Raithel, Assistant Manager August 1980 Denver Service Center William Ehorn, Superintendent August 1980 Channel Islands Natfonal Park APPROVED: Howard H. Chapman, Regional Director September 1980 Western Region GENERAL MANAGEMENT PLAN ANACAPA-SANTA BARBARA-SAN MIGUEL ISLANDS CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK i _J _.... --- ABSTRACT The resource management plan for Channel Islands National Park discusses cultural and natural resources and deals primarily with currently identified problems as well as proposed solutions for the three islands currently managed by the National Park Service. Initial sections provi•de background information regarding the park and influences on its resources and discuss the role of research within the park. Separate sections deal with each resource type. Specific resource problems that require management action are identified, and actions are recommended to either obtain additional information or to solve the identified problem. Impacts likely· to result from the recommended actions are noted. Few alternatives are discussed for an identified problem because few alternatives were identified as feasible. Further study is required before actions with the potential for significant -

BAWSCA Turf Replacement Program Plant List Page 1 Species Or

BAWSCA Turf Replacement Program Plant List Page 1 Species or Cultivar Common name Irrigation Irrigation (1) Requirement Type (2) Native Coastal Peninsula Bay East Salinity (3) Tolerance Abutilon palmeri INDIAN MALLOW 1 S √ √ √ √ Acer buergerianum TRIDENT MAPLE 2 T √ H Acer buergerianum var. formosanum TRIDENT MAPLE 2 T √ Acer circinatum VINE MAPLE 2 S √ √ √ √ Acer macrophyllum BIG LEAF MAPLE 2 T √ √ L Acer negundo var. californicum BOX ELDER 2 T √ √ Achillea clavennae SILVERY YARROW 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea millefolium COMMON YARROW 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea millefolium 'Borealis' COMMON YARROW 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea millefolium 'Colorado' COMMON YARROW 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea millefolium 'Paprika' COMMON YARROW 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea millefolium 'Red Beauty' COMMON YARROW 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea millefolium 'Summer Pastels' COMMON YARROW 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea 'Salmon Beauty' 1 P √ √ √ M Achillea taygetea 1 P √ √ √ Achillea 'Terracotta' 1 P √ √ √ Achillea tomentosa 'King George' WOLLY YARROW 1 P √ √ √ Achillea tomentosa 'Maynard's Gold' WOLLY YARROW 1 P √ √ √ Achillea x kellereri 1 P √ √ √ Achnatherum hymenoides INDIAN RICEGRASS 1 P √ √ √ √ Adenanthos sericeus WOOLYBUSH 1 S √ √ √ Adenostoma fasciculatum CHAMISE 1 S √ √ √ √ Adenostoma fasciculatum 'Black Diamond' CHAMISE 1 S √ √ √ √ Key (1) 1=Least 2=Intermediate 3=Most (2) P=Perennial; S=Shrub; T=Tree (3) L=Low; M=Medium; H=High 1/31/2012 BAWSCA Turf Replacement Program Plant List Page 2 Species or Cultivar Common name Irrigation Irrigation (1) Requirement Type (2) Native Coastal Peninsula Bay East Salinity (3) Tolerance Adenostoma fasciculatum 'Santa Cruz Island' CHAMISE 1 S √ √ √ √ Adiantum jordnaii CALIFORNIA MAIDENHAIR 1 P √ √ √ √ FIVE -FINGER FERN, WESTERN Adiantum pedatum MAIDENHAIR 2 P √ √ √ √ FIVE -FINGER FERN, WESTERN Adiantum pedatum var. -

International Oaks No. 22.Pdf

INTERNATIONAL OAKS The Journal of the International Oak Society Issue No. 22 Spring 2011 ISSN 1941 2061 Spring 2011 International Oak Journal No. 22 1 The International Oak Society Officers and Board of Directors, 2009 Editorial Office: Membership Office: Béatrice Chassé (France), President Guy Sternberg (USA) Rudy Light (USA) Charles Snyers d'Attenhoven (Belgium), Starhill Forest 11535 East Road Vice-President 12000 Boy Scout Trail Redwood Valley, CA Jim Hitz (USA), Secretary Petersburg, IL 95470 US William Hess (USA), Treasurer 62675-9736 [email protected] Rudy Light (USA), Membership Director e-mail: Dirk Benoît (Belgium), [email protected] Tour Committee Director Allan Taylor (USA), Ron Allan Taylor (USA)USA) Editor, Oak News & Notes 787 17th Street Allen Coombes (Mexico), Boulder, CO 80302 Development Director [email protected] Guy Sternberg (USA), 303-442-5662 Co-editor, IOS Journal Ron Lance (USA), Co-editor, IOS Journal Anyone interested in joining the International Oak Society or ordering information should contact the membership office or see the wesite for membership enrollment form. Benefits include International Oaks and Oak News and Notes publications, conference discounts, and exchanges of seeds and information among members from approximately 30 nations on six continents. International Oak Society website: http://www.internationaloaksociety.org ISSN 1941 2061 Cover photos: Front: Quercus chrysolepsis Liebm. or Uncle Oak, of Palomar Mountain photo©Guy Sternberg Back: Quercus alentejana (a new species) foliage and fruits photos©Michel Timacheff 2 International Oak Journal No. 22 Spring 2011 Table of Contents Message from the Editor Guy Sternberg ..................................................................................................5 Paternity and Pollination in Oaks: Answers Blowin’ in the Wind Mary V. -

Download PDF File Concordia Arboretum at Meek Tech Tree Walk

Concordia Arboretum at Meek Tech Tree Walk LEARNING LANDSCAPES Concordia Arboretum at Meek Tech Tree Walk 2015 Learning Landscapes Site data collected in Summer 2014. Written by: Kat Davidson, Karl Dawson, Angie DiSalvo, Jim Gersbach and Jeremy Grotbo Portland Parks & Recreation Urban Forestry 503-823-TREE [email protected] http://portlandoregon.gov/parks/learninglandscapes Cover photos (from top left to bottom right): 1) Fruit and foliage of a Celtis bungeana. 2) The spreading canopy of a blue oak. 3) A pair of tall Sequoia sempervirens. 4) Quercus tomentella acorns. 5) Clustered acorns of a bur oak. 6) Sunlight shines through a California black oak leaf. 7) A winged hackberry growing in an arboretum. 8) The rarely-seen fl owers of an Emmenopterys henryi. Photo above: 1) A large canyon live oak growing in its native range. ver. 1/28/2015 Portland Parks & Recreation 1120 SW Fifth Avenue, Suite 1302 Portland, Oregon 97204 (503) 823-PLAY Commissioner Amanda Fritz www.PortlandParks.org Director Mike Abbaté The Learning Landscapes Program Concordia Arboretum at Meek Tech The Concordia Arboretum at Meek Tech Learning Landscape was initiated in December 2010 with a planting of 28 trees. It showcases evergreen and deciduous oaks as well as relict, monotypic species. This tree walk identifi es trees planted as part of the Learning Landscape as well as other specimens at the school. What is a Learning Landscape? A Learning Landscape is a collection of trees planted and cared for at a school by students, volunteers, and Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) Urban Forestry staff. Learning Landscapes offer an outdoor educational experience for students, as well as environmental and aesthetic benefi ts to the school and surrounding neighborhood. -

Lausd Approved Plant List 2012 Trees

LAUSD APPROVED PLANT LIST 2012 TREES CA Botanical Name Common Name Native Notes Tolerates seasonal flooding. Mature trees create heavy litter. Light shade. Highly allergenic, use Acacia stenophylla Shoestring acacia sparingly. Acer macrophyllum Big leaf maple x High water use. See Bioswale list. Afrocarpus gracilior (Podocarpus gracilior) Fern pine Agonis flexuosa Peppermint tree Agonis flexuosa 'Jervis Bay After After Dark peppermint Dark' tree Dark purple leaves and red stems. Albizzia julibrissin Silk tree Not as good near the coast. Allocasuarina verticillata Drooping she-oak, Coast (Casuarina stricta) beefwood Highly allergenic, use sparingly. Alnus rhombifolia White alder x High water use. See Bioswale list. Arbutus 'Marina' Marina strawberry tree Arbutus unedo Strawberry tree Bauhinia blakeana Hong Kong orchid tree Bauhinia variegata (purpurea) Purple orchid tree Brachychiton acerifolius Australian flame tree Brachychiton rupestris Narrow-leaf bottle tree Very wide bottle shaped trunk. Callistemon viminalis Weeping bottle brush Calocedrus decurrens Incense cedar x Cassia leptophylla Gold medallion tree Casuarina cunninghamiana River she-oak Highly allergenic, use sparingly. Catalpa bignonioides Common catalpa Good for lawns. Catalpa speciosa Western catalpa Good for lawns. Cedrus atlantica Atlas cedar Cedrus atlantica ‘Glauca’ Blue atlas cedar Cedrus deodara Deodar cedar Cedrus libani Cedar of Lebanon Small fruits feed native birds Western or Net-leaf through winter. Can be limbed up Celtis reticulata hackberry x for tree form. TREES CA Botanical Name Common Name Native Notes Male trees are high allergen producers. Females produce edible Ceratonia siliqua Carob tree pods. Site appropriately. Cercis occidentalis Western redbud x Desert willow (e.g. Burgundy Lace, Warren Jones evergreen desert Chilopsis linearis and cultivars willow) x Does better away from the coast. -

Oak Species, Varieties, and Hybrids in California by Lineage Group (Subgenus) Life Form Red Oaks (Erythrobalanus)

Oak Species, Varieties, and Hybrids in California by Lineage Group (Subgenus) Life Form Red Oaks (Erythrobalanus) *Quercus agrifolia Coast Live Oak ET Quercus agrifolia var. oxyadenia (var. in S. Cal and Baja) ET Quercus ilex1 Holly Oak (native to Med.) ET *Quercus kelloggii California Black Oak DT Quercus parvula var. parvula Santa Cruz Island Oak ES *Quercus parvula var. shrevei Shreve Oak ET *Quercus parvula var. tamalpaisensis Tamalpais oak ES *Quercus wislizeni var. frutescens Dwarf Interior Live Oak ES *Quercus wislizeni var. wislizeni Interior Live Oak ET Quercus X chasei Chase Oak (Hybrid of Q. agrifolia & Q. kelloggii) DT Quercus X moreha Oracle Oak (Hybrid of Q. kelloggii & Q. wislizeni) DT Intermediate Oaks (Protobalanus) Quercus cedrosensis Cedros Island Oak ET *Quercus chrysolepis Canyon Live Oak, Golden Oak, Maul Oak ET *Quercus vaccinifolia Huckleberry Oak ES Quercus palmeri Palmers Oak ES Quercus tomentella Island Oak ET White Oaks (Lepidobalanus) *Quercus berberidifolia Scrub Oak ES *Quercus douglasii Blue Oak DT *Quercus durata var. durata Leather Oak ES Quercus durata var. gabrielensis San Gabriel oak ES *Quercus garryana var. breweri Brewer’s Oak DS *Quercus garryana var. garryana Oregon or Garry Oak DT *Quercus garryana var. semota DS *Quercus lobata Valley Oak DT *Quercus sadleriana Deer Oak ES Quercus cornelius-mulleri Muller’s Oak ES Quercus dumosa Nuttall’s Scrub oak ES Quercus engelmanii Engelmann or Mesa Oak ET Quercus john-tuckeri Tucker’s Oak ES Quercus pacifica Pacific Oak ES Quercus turbinella Shrub Live Oak ES Quercus X acutidens X acutidens (Hybrid of Q. cornelius-mulleri & Q. engelmannii) ETorS Quercus X alvordiana Alford Oak (Hybrid of Q.