Santa Catalina Island1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

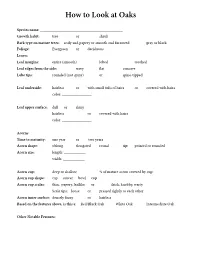

How to Look at Oaks

How to Look at Oaks Species name: __________________________________________ Growth habit: tree or shrub Bark type on mature trees: scaly and papery or smooth and furrowed gray or black Foliage: Evergreen or deciduous Leaves Leaf margins: entire (smooth) lobed toothed Leaf edges from the side: wavy fat concave Lobe tips: rounded (not spiny) or spine-tipped Leaf underside: hairless or with small tufs of hairs or covered with hairs color: _______________ Leaf upper surface: dull or shiny hairless or covered with hairs color: _______________ Acorns Time to maturity: one year or two years Acorn shape: oblong elongated round tip: pointed or rounded Acorn size: length: ___________ width: ___________ Acorn cup: deep or shallow % of mature acorn covered by cup: Acorn cup shape: cap saucer bowl cup Acorn cup scales: thin, papery, leafike or thick, knobby, warty Scale tips: loose or pressed tightly to each other Acorn inner surface: densely fuzzy or hairless Based on the features above, is this a: Red/Black Oak White Oak Intermediate Oak Other Notable Features: Characteristics and Taxonomy of Quercus in California Genus Quercus = ~400-600 species Original publication: Linnaeus, Species Plantarum 2: 994. 1753 Sections in the subgenus Quercus: Red Oaks or Black Oaks 1. Foliage evergreen or deciduous (Quercus section Lobatae syn. 2. Mature bark gray to dark brown or black, smooth or Erythrobalanus) deeply furrowed, not scaly or papery ~195 species 3. Leaf blade lobes with bristles 4. Acorn requiring 2 seasons to mature (except Q. Example native species: agrifolia) kelloggii, agrifolia, wislizeni, parvula 5. Cup scales fattened, never knobby or warty, never var. -

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014

The Jepson Manual: Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition Supplement II December 2014 In the pages that follow are treatments that have been revised since the publication of the Jepson eFlora, Revision 1 (July 2013). The information in these revisions is intended to supersede that in the second edition of The Jepson Manual (2012). The revised treatments, as well as errata and other small changes not noted here, are included in the Jepson eFlora (http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html). For a list of errata and small changes in treatments that are not included here, please see: http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/JM12_errata.html Citation for the entire Jepson eFlora: Jepson Flora Project (eds.) [year] Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html [accessed on month, day, year] Citation for an individual treatment in this supplement: [Author of taxon treatment] 2014. [Taxon name], Revision 2, in Jepson Flora Project (eds.) Jepson eFlora, [URL for treatment]. Accessed on [month, day, year]. Copyright © 2014 Regents of the University of California Supplement II, Page 1 Summary of changes made in Revision 2 of the Jepson eFlora, December 2014 PTERIDACEAE *Pteridaceae key to genera: All of the CA members of Cheilanthes transferred to Myriopteris *Cheilanthes: Cheilanthes clevelandii D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris clevelandii (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes cooperae D. C. Eaton changed to Myriopteris cooperae (D. C. Eaton) Grusz & Windham, as native Cheilanthes covillei Maxon changed to Myriopteris covillei (Maxon) Á. Löve & D. Löve, as native Cheilanthes feei T. Moore changed to Myriopteris gracilis Fée, as native Cheilanthes gracillima D. -

Birds on San Clemente Island, As Part of Our Work Toward the Recovery of the Island’S Endangered Species

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 36, Number 3, 2005 THE BIRDS OF SAN CLEMENTE ISLAND BRIAN L. SULLIVAN, PRBO Conservation Science, 4990 Shoreline Hwy., Stinson Beach, California 94970-9701 (current address: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd., Ithaca, New York 14850) ERIC L. KERSHNER, Institute for Wildlife Studies, 2515 Camino del Rio South, Suite 334, San Diego, California 92108 With contributing authors JONATHAN J. DUNN, ROBB S. A. KALER, SUELLEN LYNN, NICOLE M. MUNKWITZ, and JONATHAN H. PLISSNER ABSTRACT: From 1992 to 2004, we observed birds on San Clemente Island, as part of our work toward the recovery of the island’s endangered species. We increased the island’s bird list to 317 species, by recording many additional vagrants and seabirds. The list includes 20 regular extant breeding species, 6 species extirpated as breeders, 5 nonnative introduced species, and 9 sporadic or newly colonizing breeding species. For decades San Clemente Island had been ravaged by overgrazing, especially by goats, which were removed completely in 1993. Since then, the island’s vegetation has begun recovering, and the island’s avifauna will likely change again as a result. We document here the status of that avifauna during this transitional period of re- growth, between the island’s being largely denuded of vegetation and a more natural state. It is still too early to evaluate the effects of the vegetation’s still partial recovery on birds, but the beginnings of recovery may have enabled the recent colonization of small numbers of Grasshopper Sparrows and Lazuli Buntings. Sponsored by the U. S. Navy, efforts to restore the island’s endangered species continue—among birds these are the Loggerhead Shrike and Sage Sparrow. -

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society

A Trip to Study Oaks and Conifers in a Californian Landscape with the International Oak Society Harry Baldwin and Thomas Fry - 2018 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Aims and Objectives: .................................................................................................................................................. 4 How to achieve set objectives: ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sharing knowledge of experience gained: ....................................................................................................................... 4 Map of Places Visited: ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Itinerary .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Background to Oaks .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Cosumnes River Preserve ........................................................................................................................................ -

Notes Oak News

The NewsleTTer of The INTerNaTIoNal oak socIeTy&, Volume 15, No. 1, wINTer 2011 Fagaceae atOak the Kruckeberg News Botanic GardenNotes At 90, Art Kruckeberg Looks Back on Oak Collecting and “Taking a Chance” isiting Arthur Rice Kruckeberg in his garden in Shoreline, of the house; other species are from the southwest U.S., and VWashington–near Seattle–is like a rich dream. With over Q. myrsinifolia Blume and Q. phillyraeiodes A.Gray from Ja- 2,000 plant species on the 4 acres, and with stories to go with pan. The Quercus collection now includes about 50 species, every one, the visitor can’t hold all the impressions together some planted together in what was an open meadow and others for long. Talking with Art about his collection of fagaceae interspersed among many towering specimens of Douglas fir, captures one slice of a life and also sheds light on many other Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, the most iconic native aspects of his long leadership in botany and horticulture in the conifer. Pacific Northwest of the United States. Though the major segment of the oak collection is drawn Art Kruckeberg arrived in Seattle in 1950, at age 30, to teach from California and southern Oregon, many happy years of botany at the University of Washington. He international seed exchanges and ordering grew up in Pasadena, California, among the from gardens around the world have extended canyon live oaks (Quercus chrysolepis Liebm.) the variety. A friend in Turkey supplied Q. and obtained his doctorate at the University of trojana Webb, Q. pubescens Willd., and–an- California at Berkeley. -

Stock Block Establishment and Manipulation to Enhance Rootability of Superior Forms of Oaks for Western Gardens

2001-2002 Progress Report to the Elvenia J. Slosson Endowment Stock Block Establishment and Manipulation to Enhance Rootability of Superior Forms of Oaks for Western Gardens University of California Davis Arboretum Investigators: Ellen Zagory, M.S., Collections Manager Davis Arboretum, University of California, Davis Dr. Wes Hackett, emeritus professor Dept. of Environmental Horticulture University of California, Davis Dr. John Tucker, emeritus professor Section of Plant Biology University of California, Davis Ryan Deering, M.S., Nursery Manager Davis Arboretum, University of California, Davis 1 Introduction The University of California, Davis Arboretum has a valuable and widely recognized collection of Quercus species native to the western United States and Mexico. This collection has been nominated to the North American Plant Collections Consortium as the western repository for oaks. Within the collection are individual trees with characteristics such as small size, columnar form, and heat and drought tolerance that make them desirable for use as garden and urban landscape plants in California and other areas of the western United States. Because of the genetic variability inherent in Quercus species, these desirable individuals cannot be propagated from seed, because only a small percentage of the progeny would have the desirable characteristics of the selected mother plant. The only commercially practical means of capturing these desirable characteristics is to propagate the selected individuals by cuttings. However, these selected individuals are now 30 or more years old and are, therefore, difficult to root by stem cuttings (Olson, 1969; Morgan et al., 1980). In research with other difficult to root species it has been shown that manipulation of stock plants from which cuttings are taken is the most successful approach to increasing the rooting ability of cuttings (Maynard and Bassuk, 1987; Davis, 1988). -

Previously Unrecorded Damage to Oak, Quercus Spp., in Southern California by the Goldspotted Oak Borer, Agrilus Coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) 1 2 TOM W

THE PAN-PACIFIC ENTOMOLOGIST 84(4):288–300, (2008) Previously unrecorded damage to oak, Quercus spp., in southern California by the goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) 1 2 TOM W. COLEMAN AND STEVEN J. SEYBOLD 1USDA Forest Service-Forest Health Protection, 602 S. Tippecanoe Ave., San Bernardino, California 92408 Corresponding author: e-mail: [email protected] 2USDA Forest Service-Pacific Southwest Research Station, Chemical Ecology of Forest Insects, 720 Olive Dr., Suite D, Davis, California 95616 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. A new and potentially devastating pest of oaks, Quercus spp., has been discovered in southern California. The goldspotted oak borer, Agrilus coxalis Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Buprestidae), colonizes the sapwood surface and phloem of the main stem and larger branches of at least three species of Quercus in San Diego Co., California. Larval feeding kills patches and strips of the phloem and cambium resulting in crown die back followed by mortality. In a survey of forest stand conditions at three sites in this area, 67% of the Quercus trees were found with external or internal evidence of A. coxalis attack. The literature and known distribution of A. coxalis are reviewed, and similarities in the behavior and impact of this species with other tree-killing Agrilus spp. are discussed. Key Words. Agrilus coxalis, California, flatheaded borer, introduced species, oak mortality, Quercus agrifolia, Quercus chrysolepis, Quercus kelloggii, range expansion. INTRODUCTION Extensive mortality of coast live oak, Quercus agrifolia Ne´e (Fagaceae), Engelmann oak, Quercus engelmannii Greene, and California black oak, Q. kelloggii Newb., has occurred since 2002 on the Cleveland National Forest (CNF) in San Diego Co., California. -

95 Oak Ecosystem Restoration on Santa Catalina Island, California

95 QUANTIFICATION OF FOG INPUT AND USE BY QUERCUS PACIFICA ON SANTA CATALINA ISLAND Shaun Evola and Darren R. Sandquist Department of Biological Science, California State University, Fullerton 800 N. State College Blvd., Fullerton, CA 92834 USA Email address for corresponding author (D. R. Sandquist): [email protected] ABSTRACT: The proportion of water input resulting from fog, and the impact of canopy dieback on fog-water input, was measured throughout 2005 in a Quercus pacifica-dominated woodland of Santa Catalina Island. Stable isotopes of oxygen were measured in water samples from fog, rain and soils and compared to those found in stem-water from trees in order to identify the extent to which oak trees use different water sources, including fog drip, in their transpirational stream. In summer 2005, fog drip contributed up to 29 % of water found in the upper soil layers of the oak woodland but oxygen isotope ratios in stem water suggest that oak trees are using little if any of this water, instead depending primarily on water from a deeper source. Fog drip measurements indicate that the oak canopy in this system actually inhibits fog from reaching soil underneath the trees; however, fog may contribute additional water in areas with no canopy. Recent observations on Santa Catalina show a significant decline in oak woodlands, with replacement by non-native grasslands. The results of this study indicate that as canopy dieback and oak mortality continue additional water may become available for these invasive grasses. KEYWORDS: Fog drip, oak woodland, Quercus pacifica, Santa Catalina Island, stable isotopes, water use. -

Quercus Chrysolepis Stand

Forest Science, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 17-27. Trunk and Root Sprouting on Residual Trees After Thinning a Quercus chrysolepis Stand TIMOTHY E. PAYSEN MARCIA G. NAROG ROBERT G. TISSELL MELODY A. LARDNER ABSTRACT. Canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis Liebm.) showed sprouting patterns on root and trunk zones following forest thinning. Root sprouting was heaviest on north and east (downhill) sides of residual trees; bole sprouts were concentrated on the south and west (uphill). Root and bole sprouting appeared to be responding to different stimuli, or responding differently to the same kind of stimulus. Thinning affected sprout growth, but not sprout numbers. Sprouting responses were at the tree level rather than the thinning treatment level. Unexpected sprouting occurred in uncut control plots. Light, tempera- ture, or mechanical activity may have affected sprouting on trees in the thinned plots. A better understanding of factors affecting sprout physiology in this species is required in order to fully explain sprouting responses following stand thinning. FOR. SCI. 37(1): 17-27. ADDITIONAL KEY WORDS. Canyon live oak, Quercus chrysolepis, sprouting. ECISIONS ON MANAGEMENT of California oak forests often rely on inadeq- uate information about stand dynamics and treatment responses (Plumb D and McDonald 1981). Thinning is a practice commonly used in many forest types to enhance stand productivity, improve wildlife habitat, or develop shaded fuelbreaks. One effect of thinning, in some species, is the production of stump sprouts. Within a thinned stand, trunk or root zone (root and rootcrown inclusive) sprouting may occur on residual trees. Sprouting could reflect the inherent capability of a species, the thinning activity, or the modified environment resulting from the thinning. -

The Conservation and Restoration of the Mexican Islands, a Successful Comprehensive and Collaborative Approach Relevant for Global Biodiversity

Chapter 9 The Conservation and Restoration of the Mexican Islands, a Successful Comprehensive and Collaborative Approach Relevant for Global Biodiversity Alfonso Aguirre-Muñoz, Yuliana Bedolla-Guzmán, Julio Hernández- Montoya, Mariam Latofski-Robles, Luciana Luna-Mendoza, Federico Méndez-Sánchez, Antonio Ortiz-Alcaraz, Evaristo Rojas-Mayoral, and Araceli Samaniego-Herrera Abstract Islands are biodiversity hotspots that offer unique opportunities for applied restoration techniques that have proven to bring inspiring outcomes. The trajectory of island restoration in Mexico is full of positive results that include (1) the removal of 60 invasive mammal populations from 39 islands, (2) the identifica- tion of conservation and restoration priorities, (3) the active restoration of seabird breeding colonies through avant-garde social attraction techniques, (4) the active restoration of integrated plant communities focusing on a landscape level, (5) applied research and science-based decision-making for the management of inva- sive alien species, (6) the legal protection of all Mexican islands, and (7) biosecurity and environmental learning programs to ensure outcomes are long lasting. Still, there are many complex challenges to face in order to achieve the goal of having all Mexican islands free of invasive mammals by 2030. Keywords Islands · Mexico · Restoration · Eradication · Biosecurity · Seabirds A. Aguirre-Muñoz · Y. Bedolla-Guzmán · J. Hernández-Montoya M. Latofski-Robles · L. Luna-Mendoza · F. Méndez-Sánchez (*) A. Ortiz-Alcaraz · E. Rojas-Mayoral · A. Samaniego-Herrera Grupo de Ecología y Conservación de Islas, A. C, Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 177 A. -

Quercus Chrysolepis Lie Bm , Canyon Live Oak

Quercus chrysolepis Lie bm , Canyon Live Oak Fagaceae Beech family Dale A. Thornburgh Canyon live oak (Quercus chrysolepis), also called canyon oak, goldcup oak, live oak, maul oak, and white live oak, is an evergreen species of the far West, with varied size and form depending on the site. In sheltered canyons, this oak grows best and reaches a height of 30 m (100 ft). On exposed moun- tain slopes, it is shrubby and forms dense thickets. Growth is slow but constant, and this tree may live for 300 years. The acorns are important as food to many animals and birds. The hard dense wood is shock resistant and was formerly used for wood- splitting mauls. It is an excellent fuel wood and makes attractive paneling. Canyon live oak is also a handsome landscape tree. Habitat Native Range Canyon live oak (fig. 1) is found in the Coast Ran- ges and Cascade Range of Oregon and in the Sierra Nevada in California, from latitude 43” 85’ N. in southern Oregon to latitude 31” 00’ N. in Baja California, Mexico (9,15). In southern Oregon, it grows on the interior side of the Coast Ranges and on the lower slopes of the Cascade Range. It grows throughout the Klamath Mountains of northern California, along the coastal mountains and the western slopes of the Sierra’Nevada, and east of the redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) forest on the coast, except in the Ring Range, where it grows close to the coast. In central and southern California, canyon live oak is found on or near the summits of mountains. -

SF Street Tree Species List 2019

Department of Public Works 2019 Recommended Street Tree Species List 1 Introduction The San Francisco Urban Forestry Council periodically reviews and updates this list of trees in collaboration with public and non-profit urban forestry stakeholders, including San Francisco Public Works, Bureau of Urban Forestry and Friends of the Urban Forest. The 2019 Street Tree List was approved by the Urban Forestry Council on October 22, 2019. This list is intended to be used for the public realm of streets and associated spaces and plazas that are generally under the jurisdiction of the Public Works. While the focus is on the streetscape, e.g., tree wells in the public sidewalks, the list makes accommodations for these other areas in the public realm, e.g., “Street Parks.” While this list recommends species that are known to do well in many locations in San Francisco, no tree is perfect for every potential tree planting location. This list should be used as a guideline for choosing which street tree to plant but should not be used without the help of an arborist or other tree professional. All street trees must be approved by Public Works before planting. Sections 1 and 2 of the list are focused on trees appropriate for sidewalk tree wells, and Section 3 is intended as a list of trees that have limited use cases and/or are being considered as street trees. Finally, new this year, Section 4, is intended to be a list of local native tree and arborescent shrub species that would be appropriate for those sites in the public realm that have more space than the sidewalk planting wells, for example, stairways, “Street Parks,” plazas, and sidewalk gardens, where more concrete has been extracted.