The Political Impact of Microfinance in Senegal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO 2016 Cover The recent large-scale, systematic destruction and looting of cultural heritage has been the dominant theme at UNESCO throughout 2016. One of the Organization’s responses to these attacks on cultural heritage and cultural pluralism is the #Unite4Heritage campaign, a global movement that calls on everyone to harvest the power of culture to bring people together and to celebrate the places, objects and cultural traditions that make the world such a rich and vibrant place. This image produced for the campaign combines past and present, with the head of Buddha Shakyamuni and the face of an Erbore tribe warrior from Ethiopia. © Public Domain LACMA - Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Rod Waddington Published in 2017 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2017 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). The present license applies exclusively to the text content of this publication and to images whose copyright belongs to UNESCO. By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

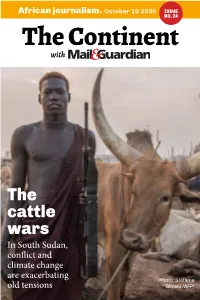

The Continent Issue 24 – 10 October 2020

African journalism. October 10 2020 ISSUE NO. 24 The Continent with The cattle wars In South Sudan, conflict and climate change are exacerbating (Photo: Stefanie old tensions Glinski/AFP) The Continent ISSUE 24. October 10 2020 Page 2 Nigerian protests go global On Friday, the most trending term on Twitter – worldwide – was #EndSARS. This caused some confusion in South Africa, where the acronym stands for the South African Revenue Service. No, South Africans, you still have to pay your taxes. In Nigeria, SARS stands for the Special Anti-Robbery Squad. They are meant to be the country’s elite police unit, but have been repeatedly implicated in intimidation, harassment, extortion, assault and murder (see our report on p6). In protests and sit-ins across the country – pictured above – Nigerians have made it clear that enough is enough. So far, however, even the police minister has been unable to shut SARS down. Inside: COVER STORY: In search of Rolls Royce (p9) pastures new, South Sudan’s Vaccines: Will Africa get its fair cattle herders are running share? (p18) into conflict with farming Zimbabwe abductions: Read communities (p11) our report in Ndebele and our ‘Racist’ Gandhi statue erected in analysis in Shona (p25) Malawi (p5) Football: Africa’s best coach is The return of Uganda’s royal now at Africa’s best club (p30) The Continent ISSUE 24. October 10 2020 Page 3 The Week in Numbers 3-million The number of pilgrims expected to travel to Touba, Senegal this week for the country’s biggest religious festival. This is despite the main ceremony being cancelled as a Covid-19 precaution. -

El Hadj Omar

El Hadj Omar Extrait du Au Senegal http://www.au-senegal.com El Hadj Omar - Français - Découvrir le Sénégal, pays de la teranga - Histoire - Date de mise en ligne : samedi 1er mars 2008 Description : Voir aussi • Les religions Au Senegal Copyright © Au Senegal Page 1/3 El Hadj Omar El Hadj Omar, chef guerrier et mystique, fondateur de lempire toucouleur. El Hadj Omar, de son vrai nom Omar Saidou Tall, est né entre 1794 et 1797 à Alwar, près de Guédé dans le département de Podor. Son père se nommait Saidou, fils de Uthman, fils de Makhtar, fils d' Ahmad Samba de la grande famille des Tall. Il était le quatrième fils de son père et le huitième de sa mère. Celle-ci avait pour nom Sokhna Adama. Omar Saidou Tall appartient à la précieuse lignée des Tooroodo et à ce titre s'initia très tôt à la culture coranique. L'ethnie à laquelle appartenait Omar Saidou Tall avait adhéré depuis 1776 à la confrérie des Qadriyas. Il reçoit de sa famille une instruction religieuse solide et apprend l'arabe. Il complète sa formation par des voyages auprès des Maures de la confrérie des Qadriya au Tagant et à Walata. A 23 ans, El Hadj Omar entreprend le pélerinage à la Mecque. Le voyage dure treize ans. Il se déplace ainsi entre le Caire, la Mecque, Médine et Jérusalem. Il séjourne quelques années à Médine, ce qui lui permet d'approfondir ses connaissances du Coran, de la culture coranique et de l'arabe. Pendant son séjour dans les lieux saints de l'islam, El Hadj Omar fait la connaissance du khalife Cheikh Muhammad Al Ghali, disciple d'Ahmad Al Tidjani, qui va exercer sur lui une influence déterminante. -

DROIT SÉNÉGALAIS N° 8 - 2009

- 1 - DROIT, POLITIQUE ET RELIGION - 3 - Faculté des sciences juridiques et politiques de Dakar Centre toulousain d’histoire du droit et des idées politiques DROIT SÉNÉGALAIS n° 8 - 2009 DROIT, POLITIQUE ET RELIGION sous la direction de Mamadou Badji, Olivier Devaux et Babacar Gueye Presses de l’Université Toulouse 1 Capitole - 5 - Copyright et diffusion : 2009 Presses de l’Université des sciences sociales de Toulouse 2 rue du doyen Gabriel Marty 31042 Toulouse cedex ISSN : 1958-3419 ISBN : 978-2-915699-91-3 - 6 - REVUE DROIT SÉNÉGALAIS Directeur de publication : M. le doyen de la Faculté des sciences juridiques et politiques Comité scientifique : - Ndiaw DIOUF - Mamadou BADJI - André CABANIS - Abdoullah CISSE - Aminata CISSE NIANG - Olivier DEVAUX - Madjiguène DIAGNE - Françoise DIENG - Seydou DIOUF - Alioune Badara FALL - Ismaïla Madior FALL - Babacar GUEYE - Ibrahima LY - El Hadj MBODJ - Isaac Yankhoba NDIAYE - Paul NGOM - Abdoulaye SAKHO - Alioune SALL - Moussa SAMB - Sylvain SANKALE - Filiga-Michel SAWADOGO - Joseph ISSA-SAYEGH - Amsatou SOW SIDIBE - Demba SY - Samba THIAM Comité de lecture : - MM. les professeurs Mamadou BADJI - André CABANIS - Françoise DIENG - 7 - - Alassane KANTE - Ibrahima LY - Michel Louis MARTIN - Demba SY - 8 - TABLE DES MATIÈRES DISCOURS D’OUVERTURE par Saïdou Nourou Tall……………………………………………. 11 LES OBJECTIFS DU COLLOQUE par Mamadou Badji……………..………………………………… 13 DE LA LAÏCITÉ À LA FRANÇAISE À LA LAÏCITÉ DANS LES CONSTITUTIONS DE L’AFRIQUE FRANCOPHONE par André Cabanis………………………………………………….. 19 LA LAÏCITÉ A L’ÉPREUVE DES FAITS AU SÉNÉGAL par Abdoulaye Dieye………………………………………………... 33 L'EGLISE CATHOLIQUE ET LES AUTORITÉS ADMINISTRATIVES FRANÇAISES AU SÉNÉGAL : DES DÉBUTS DIFFICILES par Sylvain Sankalé…………………………………………………. 55 POLITIQUE ET RELIGION EN AFRIQUE COLONIALE FRANCOPHONE : VISION ET INSTRUMENTALISATION DE L’ISLAM AU MAROC ET AU SÉNÉGAL (FIN XIXE-DÉBUT XXE SIÈCLE) par Olivier Devaux………………………………………………… 85 - 9 - Table des matières LE DROIT À L’EAU SELON L’ISLAM par Moussa Samb…………………………………………………. -

Vol.9 No.204 Tuesday. NOVEMBER 19, 2019.Cdr

www Advertize Here! eThew N TRULDYa INDEPENDENTwn Subscribe to our website https://thenewdawnliberia.com get the best of balance and accurate news, delivered daily The French Version Inside Hint... “He that is greedy of gain troubleth his own house; but he that hateth ew gifts shall live.” N TRULDYa INDEPENDENTwn VOL.9 NO. 204 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 2019 PRICE LD$40.00 -Proverbs 15:27 CBL suspends 25 % a g on remittances P11e Opposition split on a g P11e Rep. Hassan Kiazolu Mr. Benoni Urey printing new money TUESDAY NOVEMBER 19 2019 www .thenewdawnliberia.com NEW DA WN 2 Continental News France gives back sword of anti-colonial fighter rance has restored to Their official report states The curved iron, brass and leader, military commander 1893 in Bandiagara. It was here Senegal a sabre that that most of the Africa wood sword has been kept in and Muslim scholar who led the that the French seized the Fbelonged to a 19th collection in Paris' Quai Branly its leather sheath in the Tidjane brotherhood, a Sufi sword, which had a French- Century Islamic scholar and museum - approximately museum in Senegal's capital on order in West Africa. made blade and a handle r u l e r. I t i s p a r t o f a 46,000 pieces - was acquired loan from France. But Sunday's He fought French troops shaped like a bird's beak. commitment to return to its w i t h s o m e d e g r e e o f ceremony saw the item from 1857 to 1859 before French colonialists also former West African colonies duress."It's symbolic. -

L'empire Toucouleur. 1848-1897

Yves-J. Saint-Martin L'Empire toucouleur 1848-1897 Le livre africain 13, rue de Sèvres, Paris-50 (c) Le livre africain, Paris, 1970. A M. Gabriel DER/EN, à qui ce petit livre doit beaucoup. Avant-Propos Ce petit livre a pour objet de combler une lacune et de réviser un procès. Combler une lacune : il n'y a pas d'étude récente et suivie, en français, sur le sujet que nous abordons ici. On trouvera, certes, bon nombre d'articles de détail, des récits déjà anciens, mais pas de travail d'ensemble sur cet Empire toucouleur dont cependant tous les manuels d'histoire, et pas seulement en Afrique, rappellent l'existence. Réviser un procès : beaucoup de ce que l'on a pu écrire, en France surtout, sur El Hadj Omar et Ahmadou, est entaché de parti pris, parfois même de partialité haineuse et chauvine, marque d'une époque où l'on ven- geait sur le Niger les insultes subies sur le Rhin. La plume des chroniqueurs s'est souvent montrée injuste, les jugements hâtifs abondent, l'incompréhen- sion est étendue. Archives en mains, et avec l'aide des traditions recueillies du Fouta-Toro au Masina, ce livre tente de voir clair dans une histoire souvent embrouillée à plaisir, et de rétablir une vérité longtemps obscurcie. Nous ne prétendons pas avoir fait œuvre définitive ; nous souhai- tons simplement être utile, et que soit reconnue notre sincérité. LE FOUTA-TORO I Introduction Les Toucouleur: le pays et les hommes Le pays. Le cours moyen du fleuve Sénégal est constitué par une large val- lée alluviale, qui s'étend sur une longueur d'environ six cents kilomètres, de- puis le moment où le cours d'eau quitte les terrains anciens, en aval de Bakel, jusqu'à celui où il commence à construire son delta intérieur, un peu en amont de Dagàna. -

Summary Proceedings

Summary Proceedings of the Forty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors September 25-27, 1990 International Monetary Fund Washington, D.C. ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution International Standard Serial Number ISSN 0074-7025 ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution CONTENTS Page Introductory Note ix Address by the President of the United States, George Bush 1 Opening Address by the Chairman of the Boards of Governors, the Governor of the Fund and the Bank for Kenya, George Saitoti . 5 Presentation of the Forty-Fifth Annual Report by the Chairman of the Executive Board and Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, M. Camdessus 12 Discussion of Fund Policy at Second Joint Session Report by the Chairman of the Interim Committee of the Board of Governors on the International Monetary System, Michael H. Wilson 22 Statements by the Governors for Italy—Guido Carli* 25 Italy—Guido Carli 29 Indonesia—J. B. Sumarlin 33 France—Pierre Bérégovoy 38 Japan—Ryutaro Hashimoto 40 Côte d'lvoire—Kablan D. Duncan* 46 China—WANG Bingqian 52 Philippines—Jesus P. Estanislao 56 Kuwait—Sheikh Ali Al-Khalifa Al-Sabah 58 Austria—Ferdinand Lacina 61 Israel—Michael Bruno 63 Greece—Efthimios Christodoulou 67 Discussion of Fund Policy at Third Joint Session Report by the Chairman of the Joint Ministerial Committee of the Boards of Governors on the Transfer of Real Resources to Developing Countries (Development Committee) B.T.G. Chidzero 73 Statements by the Governors for Islamic Republic of Iran—Mohsen Nourbakhsh 76 Federal Republic of Germany—Karl Otto Poehl 79 United Kingdom—John Major 83 India—Madhu Dandavate 87 *Speaking on behalf of a group of countries. -

Diplomatic List

Diplomatic List Spring 2016 DEPARTMENT OF STATE PUBLICATION 11221 Office of the Chief of Protocol Revised March 18, 2016 --------------------------------------------------------------- For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all missions and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -

Les Relations Entre La Communauté Tijane Du Sénégal Et La Zawiya De Fèz

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main LES RELATIONS ENTRE LA COMMUNAUTÉ TIJANE DU SÉNÉGAL ET LA ZAWIYA DE FÈZ OUMAR KANE Professeur, Département d’Histoire Faculté des Lettres & Sciences Humaines, Dakar Paru dans les Annales de la Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines, 1994, 24 : 59-68 The Tijanya brotherhood founded by Cheikh Ahmed TIJANI in the second half of the XVIIIth century achieved a spectacular breakthrough in West Africa by the middle of the XIXth century. It was adopted and championed by the main figures of the resistance to the French colonial penetration : Cheikh Umar al-Futi TALL and Ahmadou Mahdiyu BA who were introduced to it respectively by Mohamed el-Ghali in Medina and Mohamed el- Hafez, and Id-on-Ali in Mederdra, Mauritania. Mamadou Lamine Dramé from the Gajaaga and Samba Diadana Ac also were figures of the anticolonial resistance who embraced Tijanya. Ahmadou Cheikhou, Cheikh Umar TALL's successor and eldest son, too was a tijane anticolonial hero whom Archinard's men killed in 1891, after his empire had gone through a long period of turmoil. This permitted the French, ranging from Faidherbe to Jauréguibéry and to Archinard, to invent the myth of the so-called "Tijane League" hostile to France and to Christianity, to which they wanted to oppose a "malinkese - i. e. animist - league". Provoking the return of the emigres, the fall of the Omarian Empire after the capture of Nioro in 1891 paradoxically resulted in the brotherhood being propagated and deeply sealed in Senegal. -

Classement Des Etablissements

CLASSEMENT DES ETABLISSEMENTS Session 2013 Session 2012 Etablissement Secteur Présents Admis % Indice Rang Présents Admis % Indice Rang Maison d'Education Mariama BA de PU 27 100,0 329,6 001 26 96,2 311,5 001 Gorée Prythanée Militaire Charles PU 66 97,0 254,5 002 58 96,6 244,8 002 Tchororé de Saint - Louis Institution NOTRE DAME, Rue PRC 87 98,9 248,3 003 77 98,7 239,0 003 Carde, Dakar Mikado, Dakar PRL 58 98,3 201,7 004 57 94,7 178,9 006 Ecole Privée « La Petite Ecole PRL 20 85,0 185,0 005 19 84,2 126,3 016 Bilingue », Dakar Institution Sainte Jeanne D'ARC, PRC 35 82,9 162,9 006 32 93,8 175,0 007 Boulevard de la République, Dakar Ecole Privée Birago DIOP, Dakar PRL 56 91,1 158,9 007 47 83,0 168,1 008 Cours Privés Serigne Modou Bousso PRL 14 100,0 157,1 008 Dieng MBACKE, Parcelles Assainies Cours Secondaire SACRE COEUR, PRC 346 89,6 155,5 009 288 91,3 154,5 009 Sicap Liberté 1, Dakar Lycée d’Excellence Privé Aimé PRL 27 92,6 151,9 010 38 94,7 200,0 004 CESAIRE, Saint - Louis Collège Privé Yavuz Selim, Route de PRL 82 70,7 151,2 011 53 77,4 190,6 005 Ouakam, Dakar Baccalauréat 2013 Classement des établissements Janvier 2013 1 Session 2013 Session 2012 Etablissement Secteur Présents Admis % Indice Rang Présents Admis % Indice Rang Immaculée Conception, rue Pinet PRC 98 88,8 135,7 012 87 94,3 126,4 015 Laprade, Dakar Cours Sainte Marie de Hann, Dakar PRC 160 85,0 130,0 013 151 82,1 132,5 012 Collège SAINT GABRIEL de Thiès PRC 229 75,5 123,6 014 203 86,2 132,5 012 Ecole Privée Anne Marie JAVOUHEY, Route de Ouakam, PRC 176 78,4 111,4 015 164 -

Les Premiers Recensements Au Sénégal Et L'évolution Démographique

Les premiers recensements au Sénégal et l’évolution démographique Partie I : Présentation des documents Charles Becker et Victor Martin, CNRS Jean Schmitz et Monique Chastanet, ORSTOM Avec la collaboration de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, archivistes Ce document représente la mise en format électronique du document publié sous le même titre en 1983, qui est reproduit ici avec une pagination différente, mais en signa- lant les débuts des pages de la première version qui est à citer sour le titre : Charles Becker, Victor Martin, Jean Schmitz, Monique Chastanet, avec la collabora- tion de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, Les premiers recensements au Sé- négal et l’évolution démographique. Présentation de documents. Dakar, ORSTOM, 1983, 230 p. La présente version peut donc être citée soit selon la pagination de l’ouvrage originel, soit selon la pagination de cette version électronique, en mentionnant : Charles Becker, Victor Martin, Jean Schmitz, Monique Chastanet, avec la collabora- tion de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, Les premiers recensements au Sé- négal et l’évolution démographique. Présentation de documents. Dakar, 2008, 1 + 219 p. Dakar septembre 2008 Les premiers recensements au Sénégal et l’évolution démographique Partie I : Présentation des documents 1 Charles Becker et Victor Martin, CNRS Jean Schmitz et Monique Chastanet, ORSTOM Avec la collaboration de Jean-François Maurel et Saliou Mbaye, archivistes Kaolack - Dakar janvier 1983 1 La partie II (Commentaire des documents et étude sur l’évolution démographique) est en cours de préparation. Elle sera rédigée par les auteurs de cette première partie et par d’autres collaborateurs. Elle traitera surtout des données relatives aux effectifs de population et aux mouvements migratoires qui ont modifié profondément la configuration démographique du Sénégal depuis le milieu du 19ème siècle. -

Follow-Up Visit Report (Kooijmans 1991)

UNITED NATIONS Economic and Social Distr. GENERAL Council E/CN.4/1992/17 27 December 1991 Original: ENGLISH/FRENCH/ SPANISH COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Forty-eighth session Item 10 (a) of the provisional agenda QUESTION OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF ALL PERSONS SUBJECTED TO ANY FORM OF DETENTION OR IMPRISONMENT, IN PARTICULAR: TORTURE AND OTHER CRUEL, INHUMAN OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENT Report of the Special Rapporteurt Mr. P. Kooijmans. pursuant to Commission on Human Rights resolution 1991/38 GE.91-14275/4149B E/CN.4/1992/17 page ii CONTENTS Paragraphs Pag* Introduction 1- 5 1 Chapter I. MANDATE AND METHODS OF WORK 6 - 19 2 II. ACTIVITIES OF THE SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR 20 - 269 6 A. Urgent action 20 - 22 6 B. Implementation of Commission resolution 1991/70 23-24 6 25 - 269 7 C. Correspondence with Governments 25 - 27 7 Bahrain 28 - 31 8 Bangladesh 32 9 Belize 33 - 35 9 Brazil 36 9 Bulgaria 37 10 Burundi.... 38 10 Cameroon 39 - 40 11 Chile 41 - 47 12 China 48 - 51 15 Colombia 52 - 61 16 Cuba 62 - 65 18 Djibouti 66 20 Dominican Republic 67 - 71 20 Ecuador 72 - 86 23 Egypt 87 - 94 27 El Salvador 95 - 97 30 Equatorial Guinea 98 30 Ethiopia 99 - 101 31 Greece 102 - 105 32 Guatemala 106 - 108 34 Haiti 109 - 113 35 Honduras 114 37 India 115 - 117 37 Indonesia 118 - 124 39 Iran, Islamic Republic of 125 - 126 41 Iraq 127 - 130 41 Israel 131 - 135 44 Italy E/CN.4/1992/17 page iii CONTENTS (continued) Chapter Paragraphs Page II.