Supporting Cycling in Canadian Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cargo Bikes As a Growth Area for Bicycle Vs. Auto Trips: Exploring the Potential for Mode Substitution Behavior

Transportation Research Part F 43 (2016) 48–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part F journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trf Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: Exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior William Riggs Department of City and Regional Planning, College of Architecture and Environmental Design, California Polytechnic State University, 1 Grand Ave., San Luis Obispo, CA 93405, United States article info abstract Article history: Cargo bikes are increasing in availability in the United States. While a large body of Received 26 February 2015 research continues to investigate traditional bike transportation, cargo bikes offer the Received in revised form 15 August 2016 potential to capture trips for those that might otherwise be made by car. Data from a sur- Accepted 18 September 2016 vey of cargo bike users queried use and travel dynamics with the hypothesis that cargo and Available online 6 October 2016 e-cargo bike ownership has the potential to contribute to mode substitution behavior. From a descriptive standpoint, 68.9% of those surveyed changed their travel behavior after Keywords: purchasing a cargo bike and the number of auto trips appeared to decline by 1–2 trips per Cargo bikes day, half of the auto travel prior to ownership. Two key reasons cited for this change Bicycles Linked trips include the ability to get around with children and more gear. Regression models that Mode choice underscore this trend toward increased active transport confirm this. Based on these results, further research could include focus on overcoming weather-related/elemental barriers, which continue to be an obstacle to every day cycling, and further investigation into families modeling healthy behaviors to children with cargo bikes. -

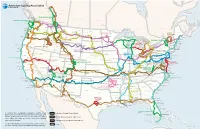

In Creating the Ever-Growing Adventure Cycling Route Network

Route Network Jasper Edmonton BRITISH COLUMBIA Jasper NP ALBERTA Banff NP Banff GREAT PARKS NORTH Calgary Vancouver 741 mi Blaine SASKATCHEWAN North Cascades NP MANITOBA WASHINGTON PARKS Anacortes Sedro Woolley 866 mi Fernie Waterton Lakes Olympic NP NP Roosville Seattle Twisp Winnipeg Mt Rainier NEW Elma Sandpoint Cut Bank NP Whitefish BRUNSWICK Astoria Spokane QUEBEC WASHINGTON Glacier Great ONTARIO NP Voyageurs Saint John Seaside Falls Wolf Point NP Thunder Bay Portland Yakima Minot Fort Peck Isle Royale Missoula Williston NOVA SCOTIA Otis Circle NORTHERN TIER NP GREEN MAINE Salem Hood Clarkston Helena NORTH DAKOTA 4,293 mi MOUNTAINS Montreal Bar Harbor River MONTANA Glendive Dickinson 380 mi Kooskia Butte Walker Yarmouth Florence Bismarck Fargo Sault Ste Marie Sisters Polaris Three Forks Theodore NORTH LAKES Acadia NP McCall Roosevelt Eugene Duluth 1,160 mi Burlington NH Bend NP Conover VT Brunswick Salmon Bozeman Mackinaw DETROIT OREGON Billings ADIRONDACK PARK North Dalbo Escanaba City ALTERNATE 395 mi Portland Stanley West Yellowstone 505 mi Haverhill Devils Tower Owen Sound Crater Lake SOUTH DAKOTA Osceola LAKE ERIE Ticonderoga Portsmouth Ashland Ketchum NM Crescent City NP Minneapolis CONNECTOR Murphy Boise Yellowstone Rapid Stillwater Traverse City Toronto Grand Teton 507 mi Orchards Boston IDAHO HOT SPRINGS NP City Pierre NEW MA Redwood NP NP Gillette Midland WISCONSIN Albany RI Mt Shasta 518 mi WYOMING Wolf Marine Ithaca YORK Arcata Jackson MINNESOTA Manitowoc Ludington City Ft. Erie Buffalo IDAHO Craters Lake Windsor Locks -

Willy WATTS 14

VOLUME 4 BO. 3 <,JARTERLY JULY 1977 { Official Organ UNICYCLING SOCIETY OF AMERICA. Inc. c 1977 ~11 Rts Rea. Yearly Membership S5 Incl~des NeVl!lletter (4) ID Card - See Blank Pg.18 OFFICERS FELI.OW UNICYCLISTS: Due to o·trcwastances beyond our control (namely a big pile of dirt and construction lfOrk) the Southland Mall in Marion Pres. Paul Fox will not be available for our National Meet races on A.ug. 20. lttempts v.Pres. R.Tschudin to secure an alternate suita'Qle location nearby have failed. We are Sec. T. ni.ck Haines therefore planning to anit the Saturday morning races and utilize that FOUNDER M:El-!BE&S part of the day this year ror a general convention type get-together where clubs and inru.viduais can meet each other, swap ideas, and display Bernard Crandall their talents and cycles. · We still plan to hold the preliminary elimi Paul & Nancy Fox nations for the group an9- trick riding later in the day at the Catholic Peter Hangach High School parking lot·. We also have the use of the Coliseum again for Patricia Herron the Sunday afternoon final~. A pan.de is still in question and if we do Bill Jenack hold one it will be JllUCh s.horter than last year. It, is hoped that every Gordon Kruse member will make a ~ec~al-effort to attend the annual business meeting Steve McPeak Sunday rooming at th(' Hpltday Inn. We have a number of V9ry important Fr. Jas. J. Moran items on the agenda (see pag~ 14 for further infomation). -

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada Prepared by Vélo Canada Bikes for the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance pre-budget consultations Submitted August 3rd, 2018 1 Investing in cycling and active transportation: Supporting economic growth in Canada Recommendations for the Government of Canada In collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, the Assembly of First Nations and additional stakeholders, implement the following recommendations: Recommendation #1: Develop a funding stream designed to rapidly increase the development and improvement of active transportation infrastructure and related traffic calming in all Canadian municipalities and in rural areas. Recommendation #2: Establish a national-level forum to consult, share, and develop a plan for moving more people and goods by bicycle in a wide variety of Canadian settings including urban, rural and remote communities. Recommendation #3: Direct Statistics Canada to collect data that will ensure the adequate and appropriate monitoring and reporting of the prevalence, potential and safety of cycling in Canadian municipalities. Use this data to set achievable evidence-based five- and ten-year transportation mode share targets for cycling. 2 Investment in bicycling represents a vastly underexploited opportunity for economic growth in Canada. If more Canadians were able to safely use a bicycle for daily transportation, there would be significant economic benefits including: a boost to economic productivity from a healthier and more productive workforce; improved mobility and personal savings for Canadians; disadvantaged groups could more easily gain skills and access employment opportunities and there would be an increase in business and tourism revenues. Increased cycling would also help to counter the negative economic costs that motorized vehicles impose on society in the form of congestion; road casualties; physical inactivity and poor health; pollution; and the political and environmental costs of maintaining fossil fuel supplies. -

Unicycle Bike Freebies and Rides for Students!

FREE UniCycle event s Bike freebies and rides for Students! FREE at your Durham Recyke Y’Bike store Shop open Wed to Sat 10.00 –17.00 www.recyke.bike l Bike lock and lights when you buy a bike*^. l Goodie bag for first 100 customers who buy a bike*. l Security marking and advice – Fri 27 Oct and Fri 1 Dec 12.00 –13.00 with Durham Constabulary. l Bike safety check (worth £10)*^. *with Durham Campus ID card from 4 Oct 2017 ^ subject to availability. Explore Bike Rides – Delivered by national charity Cycling UK who help everyone on bikes, whether you’re new to cycling, ride regularly or want to get back into it. With over 130 years’ experience we are passionate about helping more people enjoy the benefits of cycling. A series of FREE guided rides, at a gentle pace, to help you find your way around Durham and the best cycling routes to take. Booking essential. Bring your own safe working bike. Some rides include hilly sections. For more information and to book your place contact Andrew Thorp phone 07831 863770 or email [email protected]. Thurs 12 Oct Tuesday 24 Oct Saturday 4 Nov Thursday 23 Nov 5 miles 3 miles 9 miles Night Ride 3 miles 12.00 – 13.00 13.00 – 14.00 12.00 – 14.00 16.30 Meet bike stands, Meet Maiden Castle Meet St. Giles Studios, Meet St. Mary’s opposite Dept. of sports centre main Gilesgate. College main Geography. entrance. entrance. See overleaf Breeze Ride – Sat 28 Oct 14.00 – 16.00. -

CX Equipment FAQ – 2019 Page 1

Cyclocross Equipment and Regulations FAQ We publish eligibility and equipment rules for all of our National Championships on our website on the National Championship Page. Even with this published information, many of our members still call with concerns and questions about what’s legal, universally falling victim to, “someone told me”. So, here’s the 411 for cyclocross equipment: WHY In order to understand the regulations that apply to your event, please appreciate that USA Cycling and the International Cycling Union (UCI) have regulations related to cyclo-cross racing. Isn’t a bicycle a bicycle? For USA Cycling, the answer is yes, but with a few details. For the UCI, they have a robust set of regulations that, for the most part, are to make sure that what everyone understands as a bicycle, used in competition, still looks enough like a bicycle that 95% of the people in the world would recognize it. For most local events, the requirements are very basic. Because of the popularity of cyclocross(CX) in the United States, it has quickly become one of the few disciplines in our sport to truly “go international”. As many events became part of the UCI’s international calendar, suddenly, there were more rules and regulations to pay attention to. Although the principals are really the same, the details matter. Bike design, bike equipment, and tires especially, become areas of misinformation. WHAT-Regulations USA Cycling has extremely generous bicycle regulations. If it’s a pretty standard bicycle, you are welcome to race it in our events. These regulations are found in Chapter 1, specifically starting in 1I (that’s one-i). -

Cycling in the Kingdom

NVDA Northeastern Vermont Development Association Heres all the information youll need to plan your cyling excursion in the Northeast Cycling in the Kingdom Kingdom: Network Map 7 Loops Around the Block 8 Bicycling Loops and Links Back Roads to Big Falls 9 Beebe Spur n Spin 10 in Vermont’s Northeast Craftsbury Classic 11 Glacial Lakes 12 Magnificent Maples 13 Kingdom Mostly Moose 14 Pedal to Peacham 15 North-South Links North-South Link 1 16 North-South Link 3 17 The Northeast Kingdom — the 2,000-square-mile real estate jewel that North-South Link 5 18 occupies the extreme northeast corner of Vermont — was lovingly nick- North-South Link 7 19 named more than fifty years ago by a former Vermont governor and U.S. North-South Link 91 20 senator for its stunning beauty, East-West Links charm and independent spirit. East-West Link 2 21 It is without a doubt the Green East-West Link 4 22 East-West Link 6 23 Mountain state’s most beautiful Resources and undisturbed region. Com- Lodging 24 prised of Orleans, Essex and Camping 27 Caledonia counties, the North- Bicycle Shops 28 east Kingdom accounts for Bicycle Touring Companies 28 nearly one-fifth of the state’s Bicycle Touring Guidebooks 29 Bicycle Touring Maps 29 land area but only one-tenth of Trail Associations 30 its population. For those who Travel Information 30 love bicycling this is an irresistible combination — and region — that Chambers of Commerce 30 compels exploration by bicycle! For More Information 30 The Vermonter’s Vermont and great cycling Vermont has long been recognized as an international cycling destina- tion. -

CU Cycling New Rider Handbook

CU Cycling New Rider Handbook Cycling at the University of Colorado Boulder has a long history of success. Since 1988, the year of the first Collegiate National Championships, University of Colorado Boulder has produced over 65 individual National Champions and taken home 12 Team Event National titles (Road Team Time Trial and Track Team Pursuit). Additionally, we have won the Overall Team Omnium at 12 National Championships. Many University of Colorado Boulder racers have gone on to the professional ranks after graduation and achieved success at the highest level of the sport. While competition-level at the National Championships is between the elite racers on the team, conference competition is all about team participation with riders at every level contributing to the team's success. The University of Colorado Boulder is a powerhouse in the Rocky Mountain Collegiate Cycling Conference, consistently battling cross-state rival Fort Lewis College for top honors. While performance and results are important, the team actively encourages each member to reach their potential and to be their best in the University of Colorado Boulder's extraordinary range of challenging academic and extra-curricular opportunities. CU Cycling takes an active role in the larger community volunteering for various sporting and non-sporting events in Boulder and the surrounding area. version 1.0 #1 of #11 January, 2015 Table of Contents Club Organization$ 3! Club Sports 3 Officers 3 Coach 4 Member Benefits & Obligations$ 5! Sponsorships 5 Coaching 5 Dues 5 Club Functions 5 Volunteer Events 5 Fundraising 5 Racing$ 7! Racing License 7 Disciplines & Schedule 7 National Championships Qualification & Selection 10 Training Schedule$ 11 version 1.0 #2 of #11 January, 2015 Club Organization Club Sports CU Cycling is part of the Collegiate Sport Clubs Program at CU Boulder. -

On Yer Bike! Cycling at the University of Reading

On yer bike! Cycling at the University of Reading Cycling is a cheap and environmentally friendly way to get around. It also keeps you fit! We have lots of ways to help you get on your bike at the University, and encourage all our cyclists to be safe, seen and considerate. Don’t have a bike? New to cycling, or cycling Hire a bike by the hour in the UK? You can hire a Readybike from a number of docking stations Know the rules and stay safe around Reading, including two on our Whiteknights Cam- The highway code www.gov.uk/rules-for-cyclists- pus, one at London Road campus, and one at Christchurch 59-to-82 sets out all the rules for cyclists, but Green near the Sportspark. See www.readybike.co.uk for we also run courses to introduce the key ones. Great a map of all the locations, or collect a Reading Cycling map for International students or those new to cycling. from University Receptions. The cost is £1 per hour up to a maximum of £4 per day. Or you can get yearly membership Four key things you must know are: for £50. www.readybike.co.uk 1 1 You must obey traffic signs and lights. 22 You must have front and rear lights when cycling Hire a bicycle by the term or year at night or you could be fined. with Unicycle 33 It is illegal to cycle on pavements unless they are The Unicycle scheme run by RUSU loans recycled bicycles by a designated cycle route – you could be fined. -

Cycling to Work: Not Only a Utilitarian Movement but Also an Embodiment of Meanings and Experiences That Constitute Crucial

Conclusion This research analysed the different facets of utility cycling in Switzerland, using the example of commuting. We took as our starting point the concept of the cycling system, or velomobility, which underlines the importance of taking into account all elements—not only material and technical but also social, political and symbolic— which influence this practice. From this perspective, we argued that cycling—in terms of volume, frequency, distance, motivation, etc.—depends on the coming together of two potentials. The first of these is motility [11–13] or, more precisely, the indi- viduals’ cycling potential. It is built around access (‘to be able to’ use a means of transport), skills ((‘to know how to’ cycle for utility reasons) and appropriation (‘to want to’ cycle). Individuals’ appropriation of cycling depends on their perception of that mode and of its particularities, which can be interpreted as a confluence of three fundamental dimensions of mobility: movement, meaning and experience in a context of power in regards to the dominant system of automobility [6]. The second of the two potentials is the territory’s hosting potential, or its degree of bikeability, which relates to the spatial context, the available infrastructure and amenities (bicycle urbanism), as well as social and legal norms and rules. In order to identify a large sample of bicycle commuters, we focused on the bike to work scheme, which each year brings together people who commit to cycling to their place of work as often as possible during the months of May and/or June. Nearly 14,000 people completed an online questionnaire addressing the dimensions of velomobility. -

Cycling During COVID-19 Pandemic: Sports Or Lifestyle?

International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences 9(4): 765-771, 2021 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/saj.2021.090422 Cycling during COVID-19 Pandemic: Sports or Lifestyle? Didik Rilastiyo Budi1,*, Rindha Widyaningsih2, Lutfi Nur3, Boby Agustan4, Dicky Reva Apriana Sanga Dwi4, Wildan Qohhar5, Arie Asnaldi6 1Department of Physical Education, Faculty of Health Sciences, Jenderal Soedirman University, Indonesia 2Faculty of Da'wa, Prof. K.H. Saifuddin Zuhri State Islamic University, Banyumas, Central Java, Indonesia 3Department of Elementary Teacher Education, Tasikmalaya Campus, UPI, Bandung, Indonesia 4Department of Physical Education, Health and Recreation, STKIP Muhammadiyah Kuningan, West Java, Indonesia 5Departement of Physical Education, Health and Recreation, STKIP Situs Banten, Indonesia 6Faculty of Sport Science, Universitas Negeri Padang, Indonesia Received March 15, 2021; Revised June 9, 2021; Accepted June 20, 2021 Cite This Paper in the following Citation Styles (a): [1] Didik Rilastiyo Budi, Rindha Widyaningsih, Lutfi Nur, Boby Agustan, Dicky Reva Apriana Sanga Dwi, Wildan Qohhar, Arie Asnaldi , "Cycling during COVID-19 Pandemic: Sports or Lifestyle?," International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, Vol. 9, No. 4, pp. 765 - 771, 2021. DOI: 10.13189/saj.2021.090422. (b): Didik Rilastiyo Budi, Rindha Widyaningsih, Lutfi Nur, Boby Agustan, Dicky Reva Apriana Sanga Dwi, Wildan Qohhar, Arie Asnaldi (2021). Cycling during COVID-19 Pandemic: Sports or Lifestyle?. International Journal of Human Movement and Sports Sciences, 9(4), 765 - 771. DOI: 10.13189/saj.2021.090422. Copyright©2021 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The increasing trend of cycling during the the latest trends, cycling can relieve stress and increase Covid-19 pandemic is a common social phenomenon that social status indicated by the price of bicycles and reasons is common in various countries. -

CYCLO-CROSS Version on 10.06.2021

UCI CYCLING REGULATIONS PART 5 CYCLO-CROSS version on 10.06.2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter I CYCLO-CROSS EVENTS ........................................................................... 2 § 1 General Rules ...................................................................................................... 2 § 2 Event procedure .................................................................................................11 Chapter II UCI CYCLO-CROSS RANKING ................................................................16 Chapter III UCI CYCLO-CROSS WORLD CUP ..........................................................19 Chapter IV UCI MASTERS CYCLO-CROSS WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS .................23 Chapter V UCI CYCLO-CROSS TEAMS ....................................................................24 § 1 Identity ................................................................................................................24 § 2 Legal and financial status ...................................................................................25 § 3 Registration ........................................................................................................25 § 4 Contract of employment ......................................................................................27 § 5 Dissolution of a team ..........................................................................................28 § 6 Penalties .............................................................................................................28 § 7 Model contract