Chapter 6. Bicycling Infrastructure for Mass Cycling: a Transatlantic Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices Manual on Uniform Traffic

MManualanual onon UUniformniform TTrafficraffic CControlontrol DDevicesevices forfor StreetsStreets andand HighwaysHighways U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration for Streets and Highways Control Devices Manual on Uniform Traffic Dotted line indicates edge of binder spine. MM UU TT CC DD U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration MManualanual onon UUniformniform TTrafficraffic CControlontrol DDevicesevices forfor StreetsStreets andand HighwaysHighways U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration 2003 Edition Page i The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) is approved by the Federal Highway Administrator as the National Standard in accordance with Title 23 U.S. Code, Sections 109(d), 114(a), 217, 315, and 402(a), 23 CFR 655, and 49 CFR 1.48(b)(8), 1.48(b)(33), and 1.48(c)(2). Addresses for Publications Referenced in the MUTCD American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) 444 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 249 Washington, DC 20001 www.transportation.org American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association (AREMA) 8201 Corporate Drive, Suite 1125 Landover, MD 20785-2230 www.arema.org Federal Highway Administration Report Center Facsimile number: 301.577.1421 [email protected] Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) 120 Wall Street, Floor 17 New York, NY 10005 www.iesna.org Institute of Makers of Explosives 1120 19th Street, NW, Suite 310 Washington, DC 20036-3605 www.ime.org Institute of Transportation Engineers -

Written Comments

Written Comments 1 2 3 4 1027 S. Lusk Street Boise, ID 83706 [email protected] 208.429.6520 www.boisebicycleproject.org ACHD, March, 2016 The Board of Directors of the Boise Bicycle Project (BBP) commends the Ada County Highway District (ACHD) for its efforts to study and solicit input on implementation of protected bike lanes on Main and Idaho Streets in downtown Boise. BBP’s mission includes the overall goal of promoting the personal, social and environmental benefits of bicycling, which we strive to achieve by providing education and access to affordable refurbished bicycles to members of the community. Since its establishment in 2007, BBP has donated or recycled thousands of bicycles and has provided countless individuals with bicycle repair and safety skills each year. BBP fully supports efforts to improve the bicycle safety and accessibility of downtown Boise for the broadest segment of the community. Among the alternatives proposed in ACHD’s solicitation, the Board of Directors of BBP recommends that the ACHD pursue the second alternative – Bike Lanes Protected by Parking on Main Street and Idaho Street. We also recommend that there be no motor vehicle parking near intersections to improve visibility and limit the risk of the motor vehicles turning into bicyclists in the protected lane. The space freed up near intersections could be used to provide bicycle parking facilities between the bike lane and the travel lane, which would help achieve the goal of reducing sidewalk congestion without compromising safety. In other communities where protected bike lanes have been implemented, this alternative – bike lanes protected by parking – has proven to provide the level of comfort necessary to allow bicycling in downtown areas by families and others who would not ride in traffic. -

A Behavior-Based Framework for Assessing Barrier Effects to Wildlife from Vehicle Traffic Volume 1 Sandra L

CONCEPTS & THEORY A behavior-based framework for assessing barrier effects to wildlife from vehicle traffic volume 1 Sandra L. Jacobson,1,† Leslie L. Bliss-Ketchum,2 Catherine E. de Rivera,2 and Winston P. Smith3,4 1 1USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Davis, California 95618 USA 1 2Department of Environmental Science & Management, School of the Environment, 1 Portland State University, Portland, Oregon 97207-0751 USA 1 3USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, La Grande, Oregon 97850 USA 1 Citation: Jacobson, S. L., L. L. Bliss-Ketchum, C. E. de Rivera, and W. P. Smith. 2016. A behavior-based framework for assessing barrier effects to wildlife from vehicle traffic volume. Ecosphere 7(4):e01345. 10.1002/ecs2.1345 Abstract. Roads, while central to the function of human society, create barriers to animal movement through collisions and habitat fragmentation. Barriers to animal movement affect the evolution and tra- jectory of populations. Investigators have attempted to use traffic volume, the number of vehicles passing a point on a road segment, to predict effects to wildlife populations approximately linearly and along taxonomic lines; however, taxonomic groupings cannot provide sound predictions because closely related species often respond differently. We assess the role of wildlife behavioral responses to traffic volume as a tool to predict barrier effects from vehicle-caused mortality and avoidance, to provide an early warning system that recognizes traffic volume as a trigger for mitigation, and to better interpret roadkill data. We propose four categories of behavioral response based on the perceived danger to traffic: Nonresponders, Pausers, Speeders, and Avoiders. -

Cargo Bikes As a Growth Area for Bicycle Vs. Auto Trips: Exploring the Potential for Mode Substitution Behavior

Transportation Research Part F 43 (2016) 48–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part F journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trf Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: Exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior William Riggs Department of City and Regional Planning, College of Architecture and Environmental Design, California Polytechnic State University, 1 Grand Ave., San Luis Obispo, CA 93405, United States article info abstract Article history: Cargo bikes are increasing in availability in the United States. While a large body of Received 26 February 2015 research continues to investigate traditional bike transportation, cargo bikes offer the Received in revised form 15 August 2016 potential to capture trips for those that might otherwise be made by car. Data from a sur- Accepted 18 September 2016 vey of cargo bike users queried use and travel dynamics with the hypothesis that cargo and Available online 6 October 2016 e-cargo bike ownership has the potential to contribute to mode substitution behavior. From a descriptive standpoint, 68.9% of those surveyed changed their travel behavior after Keywords: purchasing a cargo bike and the number of auto trips appeared to decline by 1–2 trips per Cargo bikes day, half of the auto travel prior to ownership. Two key reasons cited for this change Bicycles Linked trips include the ability to get around with children and more gear. Regression models that Mode choice underscore this trend toward increased active transport confirm this. Based on these results, further research could include focus on overcoming weather-related/elemental barriers, which continue to be an obstacle to every day cycling, and further investigation into families modeling healthy behaviors to children with cargo bikes. -

Module 6. Hov Treatments

Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS Module 6. TABLE OF CONTENTS MODULE 6. HOV TREATMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 6.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................ 6-5 TREATMENTS ..................................................... 6-6 MODULE OBJECTIVES ............................................. 6-6 MODULE SCOPE ................................................... 6-7 6.2 DESIGN PROCESS .......................................... 6-7 IDENTIFY PROBLEMS/NEEDS ....................................... 6-7 IDENTIFICATION OF PARTNERS .................................... 6-8 CONSENSUS BUILDING ........................................... 6-10 ESTABLISH GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ............................... 6-10 ESTABLISH PERFORMANCE CRITERIA / MOES ....................... 6-10 DEFINE FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS ............................. 6-11 IDENTIFY AND SCREEN TECHNOLOGY ............................. 6-11 System Planning ................................................. 6-13 IMPLEMENTATION ............................................... 6-15 EVALUATION .................................................... 6-16 6.3 TECHNIQUES AND TECHNOLOGIES .................. 6-18 HOV FACILITIES ................................................. 6-18 Operational Considerations ......................................... 6-18 HOV Roadway Operations ...................................... 6-20 Operating Efficiency .......................................... 6-20 Considerations for 2+ Versus 3+ Occupancy Requirement ............. 6-20 Hours of Operations .......................................... -

Design Guidelines for the Use of Curbs and Curb/Guardrail

DESIGN GUIDELINES FOR THE USE OF CURBS AND CURB/GUARDRAIL COMBINATIONS ALONG HIGH-SPEED ROADWAYS by Chuck Aldon Plaxico A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Civil Engineering by September 2002 APPROVED: Dr. Malcolm Ray, Major Advisor Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. Leonard D. Albano, Committee Member Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. Tahar El-Korchi, Committee Member Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. John F. Carney, Committee Member Provost and Vice President, Academic Affairs Dr. Joseph R. Rencis, Committee Member Mechanical Engineering ABSTRACT The potential hazard of using curbs on high-speed roadways has been a concern for highway designers for almost half a century. Curbs extend 75-200 mm above the road surface for appreciable distances and are located very near the edge of the traveled way, thus, they constitute a continuous hazard for motorist. Curbs are sometimes used in combination with guardrails or other roadside safety barriers. Full-scale crash testing has demonstrated that inadequate design and placement of these systems can result in vehicles vaulting, underriding or rupturing a strong-post guardrail system though the mechanisms for these failures are not well understood. For these reasons, the use of curbs has generally been discouraged on high-speed roadways. Curbs are often essential, however, because of restricted right-of-way, drainage considerations, access control, delineation and other curb functions. Thus, there is a need for nationally recognized guidelines for the design and use of curbs. The primary purpose of this study was to develop design guidelines for the use of curbs and curb-barrier combinations on roadways with operating speeds greater than 60 km/hr. -

Cycling Safety: Shifting from an Individual to a Social Responsibility Model

Cycling Safety: Shifting from an Individual to a Social Responsibility Model Nancy Smith Lea A thesis subrnitted in conformity wR the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario lnstitute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto @ Copyright by Nancy Smith Lea, 2001 National Library Bibliothbque nationale ofCanada du Canada Aoquieit-el services MbJiographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemiettant P. la National Library of Canada to BiblioWque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or oeîî reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette dièse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fihn, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propndté du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thése. thesis nor substantial exûacts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celîe-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement. reproduits sans son pemiission. almmaîlnn. Cycling Satety: Shifting from an Indhrldual to a Social Reaponribillty Modal Malter of Arts, 2001 Sociology and ~qultyStudie8 in Education Ontario Inrtltute for *die8 in- ducati ion ot the University of Toronto ABSTRACT Two approaches to urban cycling safety were studied. In the irrdividual responsibility rnodel, the onus is on the individual for cycling safety. The social responsibiiii model takes a more coliecthrist approach as it argues for st~cturallyenabling distriûuted respansibility. -

Bicycle Master Plan

Bicycle Master Plan OCTOBER 2014 This Environmental Benefit Project is undertaken in connection with the settlement of the enforcement action taken by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation related to Article 19 of the Environmental Conservation Law. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PUBLIC PARTICIPANTS Thank you to all those who submitted responses to the online survey. Your valuable input informed many of the recommendations and design solutions in this plan. STEERING COMMITTEE: Lisa Krieger, Assistant Vice President, Finance and Management, Vice President’s Office Sarah Reid, Facilities Planner, Facilities Planning Wende Mix, Associate Professor, Geography and Planning Jill Powell, Senior Assistant to the Vice President, Finance and Management, Vice President’s Office Michael Bonfante, Facilities Project Manager, Facilities Planning Timothy Ecklund, AVP Housing and Auxiliary Enterprises, Housing and Auxiliary Services Jerod Dahlgren, Public Relations Director, College Relations Office David Miller, Director, Environmental Health and Safety Terry Harding, Director, Campus Services and Facilities SUNY Buffalo State Parking and Transportation Committee John Bleech, Environmental Programs Coordinator CONSULTANT TEAM: Jeff Olson, RA, Principal in Charge, Alta Planning + Design Phil Goff, Project Manager, Alta Planning + Design Sam Piper, Planner/Designer, Alta Planning + Design Mark Mistretta, RLA, Project Support, Wendel Companies Justin Booth, Project Support, GObike Buffalo This Environmental Benefit Project is undertaken in connection -

Chapter 3 Review Questions

Chapter 3 - Learning to Drive PA Driver’s Manual CHAPTER 3 REVIEW QUESTIONS 1. TEENAGE DRIVERS ARE MORE LIKELY TO BE INVOLVED IN A CRASH WHEN: A. They are driving with their pet as a passenger B. They are driving with adult passengers C. They are driving with teenage passengers D. They are driving without any passengers 2. DRIVERS WHO EAT AND DRINK WHILE DRIVING: A. Have no driving errors B. Have trouble driving slow C. Are better drivers because they are not hungry D. Have trouble controlling their vehicles 3. PREPARING TO SMOKE AND SMOKING WHILE DRIVING: A. Do not affect driving abilities B. Help maintain driver alertness C. Are distracting activities D. Are not distracting activities 4. THE TOP MAJOR CRASH TYPE FOR 16 YEAR OLD DRIVERS IN PENNSYLVANIA IS: A. Single vehicle/run-off-the-road B. Being sideswiped on an interstate C. Driving in reverse on a side street D. Driving on the shoulder of a highway 5. WHEN PASSING A BICYCLIST, YOU SHOULD: A. Blast your horn to alert the bicyclist B. Move as far left as possible C. Remain in the center of the lane D. Put on your four-way flashers 6. WHEN YOU DRIVE THROUGH AN AREA WHERE CHILDREN ARE PLAYING, YOU SHOULD EXPECT THEM: A. To know when it is safe to cross B. To stop at the curb before crossing the street C. To run out in front of you without looking D. Not to cross unless they are with an adult 7. IF YOU ARE DRIVING BEHIND A MOTORCYCLE, YOU MUST: A. -

High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing

High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing Project #: RES2016-05 Final Report Submitted to Tennessee Department of Transportation Principal Investigator (PI) Deo Chimba, PhD., P.E., PTOE. Tennessee State University Phone: 615-963-5430 Email: [email protected] Co-Principal Investigator (Co-PI) Janey Camp, PhD., P.E., GISP, CFM Vanderbilt University Phone: 615-322-6013 Email: [email protected] July 10, 2018 DISCLAIMER This research was funded through the State Research and Planning (SPR) Program by the Tennessee Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration under RES2016-05: High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Tennessee Department of Transportation and the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The State of Tennessee and the United States Government assume no liability of its contents or use thereof. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author(s), who are solely responsible for the facts and accuracy of the material presented. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Tennessee Department of Transportation or the United States Department of Transportation. ii Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. RES2016-05 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date: March 2018 High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Detection System Testing 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Deo Chimba and Janey Camp TDOT PROJECT # RES2016-05 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering; Tennessee State University 11. -

Exploring Changes to Cycle Infrastructure to Improve the Experience of Cycling for Families

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWE Bristol Research Repository Exploring changes to cycle infrastructure to improve the experience of cycling for families Dr William Clayton1 Dr Charles Musselwhite Centre for transport and Society Centre for Innovative Ageing Faculty of Environment and Technology School of Human and Health Sciences University of the West of England Swansea University Bristol, UK Swansea, UK BS16 1QY SA2 8PP Tel: +44 (0)1792 518696 Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 82316 Web: www.drcharliemuss.com Email: [email protected] Twitter: @charliemuss Website: www.uwe.ac.uk/et/research/cts Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS: Cycling, infrastructure, motivation, families, behaviour change. Abstract: Positive changes to the immediate cycling environment can improve the cycling experience through increasing levels of safety, but little is known about how the intrinsic benefits of cycling might be enhanced beyond this. This paper presents research which has studied the potential benefits of changing the infrastructure within a cycle network – here the National Cycle Network (NCN) in the United Kingdom (UK) – to enhance the intrinsic rewards of cycling. The rationale in this approach is that this could be a motivating factor in encouraging greater use of the cycle network, and consequently help in promoting cycling and active travel more generally amongst family groups. The project involved in-depth research with 64 participants, which included family interviews, self-documented family cycle rides, and school focus groups. The findings suggest that improvements to the cycling environment can help maintain ongoing motivation for experienced cycling families by enhancing novel aspects of a routine journey, creating enjoyable activities and facilitating other incidental experiences along the course of a route, and improving the kinaesthetic experience of cycling. -

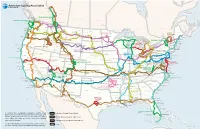

In Creating the Ever-Growing Adventure Cycling Route Network

Route Network Jasper Edmonton BRITISH COLUMBIA Jasper NP ALBERTA Banff NP Banff GREAT PARKS NORTH Calgary Vancouver 741 mi Blaine SASKATCHEWAN North Cascades NP MANITOBA WASHINGTON PARKS Anacortes Sedro Woolley 866 mi Fernie Waterton Lakes Olympic NP NP Roosville Seattle Twisp Winnipeg Mt Rainier NEW Elma Sandpoint Cut Bank NP Whitefish BRUNSWICK Astoria Spokane QUEBEC WASHINGTON Glacier Great ONTARIO NP Voyageurs Saint John Seaside Falls Wolf Point NP Thunder Bay Portland Yakima Minot Fort Peck Isle Royale Missoula Williston NOVA SCOTIA Otis Circle NORTHERN TIER NP GREEN MAINE Salem Hood Clarkston Helena NORTH DAKOTA 4,293 mi MOUNTAINS Montreal Bar Harbor River MONTANA Glendive Dickinson 380 mi Kooskia Butte Walker Yarmouth Florence Bismarck Fargo Sault Ste Marie Sisters Polaris Three Forks Theodore NORTH LAKES Acadia NP McCall Roosevelt Eugene Duluth 1,160 mi Burlington NH Bend NP Conover VT Brunswick Salmon Bozeman Mackinaw DETROIT OREGON Billings ADIRONDACK PARK North Dalbo Escanaba City ALTERNATE 395 mi Portland Stanley West Yellowstone 505 mi Haverhill Devils Tower Owen Sound Crater Lake SOUTH DAKOTA Osceola LAKE ERIE Ticonderoga Portsmouth Ashland Ketchum NM Crescent City NP Minneapolis CONNECTOR Murphy Boise Yellowstone Rapid Stillwater Traverse City Toronto Grand Teton 507 mi Orchards Boston IDAHO HOT SPRINGS NP City Pierre NEW MA Redwood NP NP Gillette Midland WISCONSIN Albany RI Mt Shasta 518 mi WYOMING Wolf Marine Ithaca YORK Arcata Jackson MINNESOTA Manitowoc Ludington City Ft. Erie Buffalo IDAHO Craters Lake Windsor Locks