Exploring Changes to Cycle Infrastructure to Improve the Experience of Cycling for Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bicycle Master Plan

Bicycle Master Plan OCTOBER 2014 This Environmental Benefit Project is undertaken in connection with the settlement of the enforcement action taken by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation related to Article 19 of the Environmental Conservation Law. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PUBLIC PARTICIPANTS Thank you to all those who submitted responses to the online survey. Your valuable input informed many of the recommendations and design solutions in this plan. STEERING COMMITTEE: Lisa Krieger, Assistant Vice President, Finance and Management, Vice President’s Office Sarah Reid, Facilities Planner, Facilities Planning Wende Mix, Associate Professor, Geography and Planning Jill Powell, Senior Assistant to the Vice President, Finance and Management, Vice President’s Office Michael Bonfante, Facilities Project Manager, Facilities Planning Timothy Ecklund, AVP Housing and Auxiliary Enterprises, Housing and Auxiliary Services Jerod Dahlgren, Public Relations Director, College Relations Office David Miller, Director, Environmental Health and Safety Terry Harding, Director, Campus Services and Facilities SUNY Buffalo State Parking and Transportation Committee John Bleech, Environmental Programs Coordinator CONSULTANT TEAM: Jeff Olson, RA, Principal in Charge, Alta Planning + Design Phil Goff, Project Manager, Alta Planning + Design Sam Piper, Planner/Designer, Alta Planning + Design Mark Mistretta, RLA, Project Support, Wendel Companies Justin Booth, Project Support, GObike Buffalo This Environmental Benefit Project is undertaken in connection -

Intersections

Design Concept for a CycleTrack On the East Side of Herndon Parkway for 2,000 Feet South of the Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Regional Park Trail Final Report Revised July 14, 2017 September 20, 2016 Prepared by: Table of Contents Introduction 3 Intersections 4 Relevant Case Studies 5 Cycle Track Approach to Intersection 8 Near-Term Recommendation: Bend-Out 8 Long-Term Recommendation: Protected Intersection 9 Intersection Crossing 10 Signal Phasing 11 Bus Stops 12 Relevant Case Studies 12 Near-Term and Future Lower-Ridership Bus Stop Recommendation: Bus Passengers Cross the Cycle Track 14 Long-Term Recommendation for High-Ridership Bus Stops: Bus Stop on an Island 14 Access Roads and Private Driveways 15 Relevant Case Studies 15 Near-Term and Future Lower-Volume Access Road/Private Driveway 17 Long-Term Recommendation for Higher Volume Assess Roads/Private Driveways: Recessed Crossing 18 Additional Considerations 19 Transitions to Adjoining Bicycle and Pedestrian Facilities 19 Stormwater Management 19 Summary of Recommended Improvements 20 Prepared by: others address long-term conditions that will likely Introduction result from increased development in the Herndon Transit-Oriented Core, opening of the Herndon An improved bicycle facility has been proposed Metrorail Station, and restructuring of the Herndon along Herndon Parkway in the Herndon Metrorail Parkway and Spring Street intersection. Stations Access Management Study (2014) and the Transportation chapter of the Town of Herndon’s The recommendations for the proposed cycle track 2030 Comprehensive Plan (2008). The Fairfax are organized as follows: County Bicycle Master Plan (2014) and Urban Design and Architectural Guidelines for the Herndon • Intersections Transit-Oriented Core (2014) defined this potential Relevant Case Studies improvement as a cycle track, separated from Approaching an intersection pedestrian and vehicular traffic. -

Highway 17 and 69 Controlled Access Highway Response

Sudbury Cyclists Union March 28, 2014 Re: Route Planning Study, Highway 17 from Sudbury to Markstay and Highway 69 from the Estaire Road Interchange to Highway 17 The Sudbury Cyclists Union (SCU) has serious concerns about how the implementation of controlled access highways have affected cyclists in the Sudbury region. We also have some specific concerns about the implementation of this project as it relates to the safety of cyclists. The intent of all provincial roadwork is to improve the safety of its users. Traditionally, the focus has been on the safety of motorized traffic. The safety of pedestrians and cyclists has been long neglected on our highways. On page 2.1 of your “Study Design Report”, you note that to “promote a multimodal transportation network” is a key provincial responsibility” as is to “be a leader in road safety”. The sole intent of implementing controlled access highways is to facilitate the safe movement of motorized traffic. While implementing such highways draws dangerous traffic away from more local routes that are used by cyclists, alternative safe and convenient routes for cyclists are often an afterthought and are not an integral part of the planning process. An example is the Highway 69 corridor leading south from the City of Greater Sudbury that has been built without guaranteeing an alternative right of way for cyclists wishing to travel south. This controlled access highway has closed off access for non-motorized users to several towns and tourist areas, including the town of Killarney and the iconic Killarney Provincial Park. In other provinces, in particular in Western Canada, major motor routes similar to our controlled highways have paved shoulders that are used by cyclists. -

Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: an Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2018 Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah Stephanie A. Tomlin Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Design Commons, and the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Tomlin, Stephanie A., "Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah" (2018). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7195. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLANNING FOR ACTIVE TRANSPORTATION IN THE WESTERN UNITED STATES: AN ALTERNATIVE FUTURE FOR CACHE VALLEY, UTAH by Stephanie A. Tomlin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Bioregional Planning Approved: Bartlett Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. Richard Toth, M.L.A. Major Professor Committee Member Jordy Guth, M.S. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2018 ii Copyright © Stephanie A. Tomlin, 2018 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Planning for Active Transportation in the Western United States: An Alternative Future for Cache Valley, Utah by Stephanie A. Tomlin, Master of Bioregional Planning Utah State University, 2018 Major Professor: Bartlett (Barty) Warren-Kretzschmar, Ph.D. -

A Feasibility Study of GIS-Based Analyses of Cycling Infrastructure

Build it: A Feasibility Study of GIS-Based Analyses of Cycling Infrastructure A thesis submitted by Ian Thistle In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning Tufts University February 2016 Adviser: Mary Davis Reader: Barbara Parmenter Table of Contents List of Figures ...................................................................................... iv List of Tables ........................................................................................ v Abstract .................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ................................................................................. vii Chapter 1: Introduction ............................................................................ 1 Chapter 2: Literature Review.................................................................... 4 Benefits of Cycling ................................................................................ 4 How can cities influence mode choice towards biking? ......................... 6 Evaluating Road Infrastructure for Cycling ............................................ 9 Analysis of Street Networks: “Build it! But Where?” ............................ 13 Chapter 3: Methods ............................................................................... 17 Step 1: Selecting the comparison methodologies ............................... 19 Step 2: Selecting the sample ............................................................. -

Smart Choices for Cities: Cycling in the City

Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Pictures © Shutterstock, 2016, pages: 1, 14, 15, 20, 22. 2 Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Table of contents Preface. 4 Introduction . 5 The city is changing . 5 Why cycling? . 8 An integrated approach to cycling provision in the urban environment. 9 Infrastructure.and.equipment. 10 Introduction. 10 Cycling safety . 10 Where do most accidents happen? . 11 Senior cyclists and safety . 12 Equipment . 12 Implications for infrastructure . 12 Building blocks for safe infrastructure . 14 Recognisability . 16 Specific infrastructural situations . 16 Multi-modal Transport. 16 Bicycle Congestion . 18 Bicycle Theft . 18 Supporting.Actions. 19 Introduction. 19 Building an organization in (local) government . 19 Working with stakeholders . 20 Cycling Association . 20 Employers: Bicycle to work . 20 Cycle Marketing . 20 Education . 21 Insights in cycling behaviour . 21 Gathering data . 21 Cycling in traffic models . 21 From.ideas.to.policy:.Recommendations.for.approaching.investments.in.cycling . 22 Bibliography. 24 Notes. 26 3 Smart choices for cities Cycling in the City Preface Thank you for reading the eighth and final policy analysis of Over 70% of all Europeans live in cities and cities are the CIVITAS WIKI Policy Analysis Series. becoming increasingly congested. Citizens suffer from poor air quality and noise, which makes the cities less liveable. The mission of the CIVITAS WIKI project was to provide This document provides information about measures that can information on clean urban transport and the CIVITAS be taken in order to increase the use of cycling as a transport Initiative to EU city planners, decision-makers and citizens. -

FLOW Portfolio of Measures: the Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing

THE ROLE OF WALKING AND CYCLING IN REDUCING CONGESTION A PORTFOLIO OF MEASURES A PORTFOLIO OF MEASURES FLOW DOCUMENT TITLE The Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing Congestion: A Portfolio of Measures AUTHORS Thorsten Koska, Frederic Rudolph (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie gGmbH); Case Studies: Benjamin Schreck, Andreas Vesper (Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen), Tamás Halmos (Budapesti Közlekedési Központ), Tamás Mátrai (Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem), Alicja Pawłowska (Municipality of Gdynia), Jacek Oskarbski (Politechnika Gdanska), Benedicte Swennen (European Cyclists’ Federation), Nora Szabo (PTV AG), Graham Cavanagh (Rupprecht Consult GmbH), Florence Lepoudre (Traject), Katie Millard (Transport Research Laboratory), Martin Wedderburn (Walk21), Miriam Müller, David Knor (Wuppertal Institut für Klima, Umwelt, Energie gGmbH) CONTACT Project coordinator: Rupprecht Consult Bernard Gyergyay: [email protected] Kristin Tovaas: [email protected] Project dissemination manager: Polis Daniela Stoycheva: [email protected] CITATION FLOW Project (2016). The Role of Walking and Cycling in Reducing Congestion: A Portfolio of Measures. Brussels. Available at http://www.h2020-flow.eu. IMAGE DISCLAIMER The images in this document are used as a form of visual citation to support and clarify statements made in the text. The authors have made great effort to provide credit for every image used. If, despite our efforts, we have not given sufficient credit to the author of any images used, please contact us directly at [email protected] LAYOUT PEAK Sourcing DATE July 2016 The sole responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the European Union. Neither the INEA nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. -

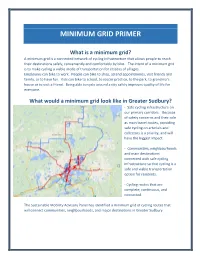

Minimum Grid Primer

MINIMUM GRID PRIMER What is a minimum grid? A minimum grid is a connected network of cycling infrastructure that allows people to reach their destinations safely, conveniently and comfortably by bike. The intent of a minimum grid is to make cycling a viable mode of transportation for citizens of all ages. Employees can bike to work. People can bike to shop, attend appointments, visit friends and family, or to have fun. Kids can bike to school, to soccer practice, to the park, to grandma’s house or to visit a friend. Being able to cycle around a city safely improves quality of life for everyone. What would a minimum grid look like in Greater Sudbury? - Safe cycling infrastructure on our primary corridors. Because of safety concerns and their role as main travel routes, providing safe cycling on arterials and collectors is a priority, and will have the biggest impact. - Communities, neighbourhoods and main destinations connected with safe cycling infrastructure so that cycling is a safe and viable transportation option for residents. - Cycling routes that are complete, continuous, and connected. The Sustainable Mobility Advisory Panel has identified a minimum grid of cycling routes that will connect communities, neighbourhoods, and major destinations in Greater Sudbury. Why is it important to have safe cycling on our busiest streets first? A transportation network relies on primary routes that secondary routes feed into and out of. This is true of any type of transportation, including cycling. The primary network needs to be constructed first, otherwise the transportation network is fragmented - the secondary routes do not connect to anything. -

Cycling Infrastructure Version 1

Cycling VERSION 1 infrastructure Cycling infrastructure In this chapter 01 Introduction 5 Kerbside activity 33 07 02 Choosing the right facility 6 General Design 35 08 2.1 Design parameters 6 8.1 Design controls 35 2.2 Types of cycle facility 8 8.2 Horizontal and vertical alignment 39 8.3 Widths and clearances 41 03 Approved facilities within the road reserve 11 8.4 Construction 45 3.1 Separated cycleway (busy, fast, or heavy traffic) 11 8.5 Drainage 46 3.2 Separated cycleway (low volume and slow traffic) 14 8.6 Signs and markings 47 3.3 Alternatives requiring specific approval 15 8.7 Lighting 48 3.4 Mixed traffic streets 16 3.5 Cycle streets 16 Ancillary features 49 09 3.6 Pedestrian priority areas (cycling and pedestrians) 17 3.7 Interim facilities 20 Design for maintenance 52 10 Appendix A 04 Other infrastructure 22 Cycle parking 53 4.1 Buffered cycle lanes 22 A.1 Introduction 53 4.2 Cycle lanes 23 A.2 Bicycle Parking General principles 54 4.3 Cycle lanes between other traffic lanes 23 A.3 Categories of bicycle parking 56 4.4 Shared paths 24 A.4 Types of bicycle parking 58 A.5 Types of bicycle stands 64 05 Off road cycle paths 25 A.6 Bicycle parking placement 67 A.7 Bicycle parking access 68 06 Intersections 26 A.8 Bicycle stand materials 68 6.1 Cycleway intersections 27 A.9 Signage and wayfinding for bicycle parking 68 6.2 Roundabouts 27 A.10 Bicycle parking demand 69 6.3 Signalised intersections 28 A.11 Bicycle parking at public transport terminals 70 6.4 Unsignalised intersections 30 A.12 Bicycle parking provisioning process 71 6.5 Midblock crossing 31 A.13 Building and installation 72 6.6 Vehicle crossings 32 A.14 Operation and maintenance 72 5794_20.04.21 2 TDM | ENGINEERING DESIGN CODE 3 Cycling infrastructure 01 Introduction PURPOSE Cycling infrastructure includes facilities that are dedicated for cycle use, as well as specific standards for general infrastructure to meet the needs of cycle users. -

LCDS Chapter 6 Signs and Markings

London Cycling Design Standards [Chapter 6] Signs and markings | Contents 6. Signs and markings This chapter gives an overview of requirements on signing 6.2 Surface markings 06 to support cycling, both for dedicated infrastructure and 6.2.1 General requirements 06 for cyclists’ general use of the highway. 6.2.2 Lane markings 06 6.2.3 Give way markings 08 6.1 Signing requirements 01 6.2.4 Other markings for cycle tracks 09 6 .1.1 Signing principles 01 6.2.5 Cycle symbols and direction signing 10 6.1.2 Applying the principles 01 6.2.6 Coloured surfacing 13 6.1.3 Regulatory changes 02 6.1.4 Signs requiring enforcement 03 6.3 Signs 14 6.1.5 Signing to support wayfinding 04 6.3.1 Direction signs 14 6.3.2 Off-highway direction signs 16 6.3.3 Warning signs 16 6.3.4 Signs for pedestrian zones 17 6.3.5 Signs to minimise or avoid 18 6.3.6 Minimising sign clutter 18 6.3.7 Sign installation and mounting 21 6.4 Schedule of signs 23 Bibliography 29 Version control Version 1 (Dec 2014) – Published Q12 Version 2 (Sept 2016) – Amendments throughout following publication of TSRGD (2016) London Cycling Design Standards [Chapter 6] Signing requirements 01 Signing plays an important role in supporting and Figure 6.1 Key signing considerations in CLoS 6.1 Signing requirements enforcing safer, more comfortable, legible and coherent cycling infrastructure. Road signs and Factor Indicator Relates in this markings are defined, together, as ‘traffic signs’ chapter to 6.1.1 Signing principles within the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. -

A Review of the Evidence on Cycle Track Safety Paul Schimek, Ph.D

A Review of the Evidence on Cycle Track Safety Paul Schimek, Ph.D. October 11, 2014 This memo reviews the evidence on cycle track safety. As used by bicycling advocates in North America in recent years, the terms “cycle track” or “protected bike lane” refer to a segregated path for bicyclists adjacent to an urban roadway with a curb or raised object between the bicycle path and the portion of the road used by vehicular traffic and, in some cases, also between the portion used by pedestrians. Scandinavia, Germany, and the Netherlands have the most experience with urban bicycle paths adjacent to roads, the best data, and the most comprehensive studies. In addition to a review of the best of these studies, the memo includes a review of all of the studies of cycle tracks in North America that have been conducted in the past five years. The Netherlands A 1988 Dutch study analyzed 5,763 injury crashes recorded by police between 1973 and 1977 in 14 municipalities of more than 50,000 people.1 The share of cyclists and moped users from road traffic counts was compared to the share of cyclist and moped user injuries in police reports, according to location (intersection or road segment) and according to facility type (bike lane, cycle track, or mixed traffic). The traffic counts were multiplied by road length for the segments and by the number of intersections for the intersections. For bicyclists using bicycle paths, there was a 24% reduction in risk along segments, but a 32% increase in risk in intersections, compared to bicyclists in mixed traffic (with no separate bicycle facilities). -

Traffic-Light Intersections

Give Cycling a Push Infrastructure Implementation Fact Sheet INFRASTRUCTURE/ INTERSECTIONS AND CROSSINGS TRAFFIC-LIGHT INTERSECTIONS Overview Traffic-light intersections are inherently dangerous for cyclists. However, they are indispensable when cyclists cross heavy traffic flows. Cycle-friendly design must make cyclists clearly visible, allow short and easy maneuvers and reduce waiting time, such as a right-turn bypass or an advanced stop-line. On main cycle links, separate cycle traffic light and cycle-friendly light regulation can privilege cycle flows over motorized traffic. Background and Objectives Function Intersections are equipped with a traffic control system when they need to handle large flows of motorized traffic on the busiest urban roads, often with multiple lanes. A cycle-friendly design can greatly improve safety, speed and comfort, by increasing visibility, facilitating maneuvers and reducing waiting time. Scope Traffic-light intersections are always a second-best solution for cyclists, in terms of safety. Actually, traffic light intersections with four branches are very dangerous and should be avoided in general. Dutch guidance states that roundabouts are significantly safer than traffic lights for four- branch intersections of 10,000 to 20,000 pcu/day. In practice, traffic lights are used when an intersection needs to handle large flows of motorized traffic speedily. They can handle up to 30,000 pcu/day, more than is possible with a roundabout. These will typically include at least one very busy distributor road with multiple traffic lanes (50 km/h in the built-up area, higher outside the built-up area). Often, these busy roads are also of great interest as cycle links.