Pop-Up Placemaking Tool Kit Projects That Inspire Change — and Improve Communities for People of All Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bicycle Master Plan

Bicycle Master Plan OCTOBER 2014 This Environmental Benefit Project is undertaken in connection with the settlement of the enforcement action taken by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation related to Article 19 of the Environmental Conservation Law. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PUBLIC PARTICIPANTS Thank you to all those who submitted responses to the online survey. Your valuable input informed many of the recommendations and design solutions in this plan. STEERING COMMITTEE: Lisa Krieger, Assistant Vice President, Finance and Management, Vice President’s Office Sarah Reid, Facilities Planner, Facilities Planning Wende Mix, Associate Professor, Geography and Planning Jill Powell, Senior Assistant to the Vice President, Finance and Management, Vice President’s Office Michael Bonfante, Facilities Project Manager, Facilities Planning Timothy Ecklund, AVP Housing and Auxiliary Enterprises, Housing and Auxiliary Services Jerod Dahlgren, Public Relations Director, College Relations Office David Miller, Director, Environmental Health and Safety Terry Harding, Director, Campus Services and Facilities SUNY Buffalo State Parking and Transportation Committee John Bleech, Environmental Programs Coordinator CONSULTANT TEAM: Jeff Olson, RA, Principal in Charge, Alta Planning + Design Phil Goff, Project Manager, Alta Planning + Design Sam Piper, Planner/Designer, Alta Planning + Design Mark Mistretta, RLA, Project Support, Wendel Companies Justin Booth, Project Support, GObike Buffalo This Environmental Benefit Project is undertaken in connection -

Exploring Changes to Cycle Infrastructure to Improve the Experience of Cycling for Families

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UWE Bristol Research Repository Exploring changes to cycle infrastructure to improve the experience of cycling for families Dr William Clayton1 Dr Charles Musselwhite Centre for transport and Society Centre for Innovative Ageing Faculty of Environment and Technology School of Human and Health Sciences University of the West of England Swansea University Bristol, UK Swansea, UK BS16 1QY SA2 8PP Tel: +44 (0)1792 518696 Tel: +44 (0) 117 32 82316 Web: www.drcharliemuss.com Email: [email protected] Twitter: @charliemuss Website: www.uwe.ac.uk/et/research/cts Email: [email protected] KEYWORDS: Cycling, infrastructure, motivation, families, behaviour change. Abstract: Positive changes to the immediate cycling environment can improve the cycling experience through increasing levels of safety, but little is known about how the intrinsic benefits of cycling might be enhanced beyond this. This paper presents research which has studied the potential benefits of changing the infrastructure within a cycle network – here the National Cycle Network (NCN) in the United Kingdom (UK) – to enhance the intrinsic rewards of cycling. The rationale in this approach is that this could be a motivating factor in encouraging greater use of the cycle network, and consequently help in promoting cycling and active travel more generally amongst family groups. The project involved in-depth research with 64 participants, which included family interviews, self-documented family cycle rides, and school focus groups. The findings suggest that improvements to the cycling environment can help maintain ongoing motivation for experienced cycling families by enhancing novel aspects of a routine journey, creating enjoyable activities and facilitating other incidental experiences along the course of a route, and improving the kinaesthetic experience of cycling. -

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances

Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i iv . Pedestrian and Bicycle Friendly Policies, Practices, and Ordinances November 2011 i The Delaware Valley Regional Planning The symbol in our logo is Commission is dedicated to uniting the adapted from region’s elected officials, planning the official professionals, and the public with a DVRPC seal and is designed as a common vision of making a great region stylized image of the Delaware Valley. even greater. Shaping the way we live, The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole while the diagonal bar signifies the work, and play, DVRPC builds Delaware River. The two adjoining consensus on improving transportation, crescents represent the Commonwealth promoting smart growth, protecting the of Pennsylvania and the State of environment, and enhancing the New Jersey. economy. We serve a diverse region of DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding nine counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, sources including federal grants from the Montgomery, and Philadelphia in U.S. Department of Transportation’s Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Gloucester, and Mercer in New Jersey. and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey DVRPC is the federally designated departments of transportation, as well Metropolitan Planning Organization for as by DVRPC’s state and local member the Greater Philadelphia Region — governments. The authors, however, are leading the way to a better future. solely responsible for the findings and conclusions herein, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. -

Intersections

Design Concept for a CycleTrack On the East Side of Herndon Parkway for 2,000 Feet South of the Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Regional Park Trail Final Report Revised July 14, 2017 September 20, 2016 Prepared by: Table of Contents Introduction 3 Intersections 4 Relevant Case Studies 5 Cycle Track Approach to Intersection 8 Near-Term Recommendation: Bend-Out 8 Long-Term Recommendation: Protected Intersection 9 Intersection Crossing 10 Signal Phasing 11 Bus Stops 12 Relevant Case Studies 12 Near-Term and Future Lower-Ridership Bus Stop Recommendation: Bus Passengers Cross the Cycle Track 14 Long-Term Recommendation for High-Ridership Bus Stops: Bus Stop on an Island 14 Access Roads and Private Driveways 15 Relevant Case Studies 15 Near-Term and Future Lower-Volume Access Road/Private Driveway 17 Long-Term Recommendation for Higher Volume Assess Roads/Private Driveways: Recessed Crossing 18 Additional Considerations 19 Transitions to Adjoining Bicycle and Pedestrian Facilities 19 Stormwater Management 19 Summary of Recommended Improvements 20 Prepared by: others address long-term conditions that will likely Introduction result from increased development in the Herndon Transit-Oriented Core, opening of the Herndon An improved bicycle facility has been proposed Metrorail Station, and restructuring of the Herndon along Herndon Parkway in the Herndon Metrorail Parkway and Spring Street intersection. Stations Access Management Study (2014) and the Transportation chapter of the Town of Herndon’s The recommendations for the proposed cycle track 2030 Comprehensive Plan (2008). The Fairfax are organized as follows: County Bicycle Master Plan (2014) and Urban Design and Architectural Guidelines for the Herndon • Intersections Transit-Oriented Core (2014) defined this potential Relevant Case Studies improvement as a cycle track, separated from Approaching an intersection pedestrian and vehicular traffic. -

Approved-Bicycle-Master-Plan-Framework-Report.Pdf

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK abstract This report outlines the proposed framework for the Montgomery County Bicycle Master Plan. It defines a vision by establishing goals and objectives, and recommends realizing that vision by creating a bicycle infrastructure network supported by policies and programs that encourage bicycling. This report proposes a monitoring program designed to make the plan implementation process both clear and responsive. 2 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK contents 4 Introduction 6 Master Plan Purpose 8 Defining the Vision 10 Review of Other Bicycle Plans 13 Vision Statement, Goals, Objectives, Metrics and Data Requirements 14 Goal 1 18 Goal 2 24 Goal 3 26 Goal 4 28 Goals and Objectives Considered but Not Recommended 30 Realizing the Vision 32 Low-Stress Bicycling 36 Infrastructure 36 Bikeways 55 Bicycle Parking 58 Programs 58 Policies 59 Prioritization 59 Bikeway Prioritization 59 Programs and Policies 60 Monitoring the Vision 62 Implementation 63 Accommodating Efficient Bicycling 63 Approach to Phasing Separated Bike Lane Implementation 63 Approach to Implementing On-Road Bicycle Facilities Incrementally 64 Selecting A Bikeway Recommendation 66 Higher Quality Sidepaths 66 Typical Sections for New Bikeway Facility Types 66 Intersection Templates A-1 Appendix A: Detailed Monitoring Report 3 MONTGOMERY COUNTY BICYCLE MASTER PLAN FRAMEWORK On September 10, 2015, the Planning Board approved a Scope of Work for the Bicycle Master Plan. Task 4 of the Scope of Work is the development of a methodology report that outlines the approach to the Bicycle Master Plan and includes a discussion of the issues identified in the Scope of Work. -

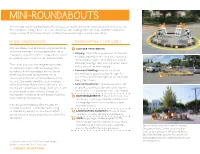

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-Roundabouts Or Neighborhood Traffic Circles Are an Ideal Treatment for Minor, Uncontrolled Intersections

MINI-ROUNDABOUTS Mini-roundabouts or neighborhood traffic circles are an ideal treatment for minor, uncontrolled intersections. The roundabout configuration lowers speeds without fully stopping traffic. Check out NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide or FHWA’s Roundabout: An Information Guide Design Guide for more details. 4 DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS COMMON MATERIALS CATEGORIES 1 2 Mini-roundabouts can be created using raised islands 1 SURFACE TREATMENTS: and simple markings. Landscaping elements are an » Striping: Solid white or yellow lines can be used important component of the roundabout and should in conjunction with barrier element to demarcate be explored even for a short-term demonstration. the roundabout space. Other likely uses include crosswalk markings: solid lines to delineate cross- The roundabout should be designed with careful walk space and / or zebra striping. consideration to lane width and turning radius for vehicles. A mini-roundabout on a residential » Pavement Markings: May include shared lane markings to guide bicyclists through the street should provide approximately 15 ft. of 2 clearance from the corner to the widest point on intersection and reinforce rights of use for people the circle. Crosswalks should be used to indicate biking. (Not shown) where pedestrians should cross in advance of the » Colored treatments: Colored pavement or oth- roundabout. Shared lane markings (sharrows) should er specialized surface treatments can be used to be used to guide people on bikes through the further define the roundabout space (not shown). intersections, in conjunction with bicycle wayfinding 2 BARRIER ELEMENTS: Physical barriers (such as route markings if appropriate. delineators or curbing) should be used to create a strong edge that sets the roundabout apart Note: Becase roundabouts allow the slow, but from the roadway. -

How to Drive, Walk & Bike in a Roundabout

What do the signs at a REMEMBER roundabout mean? Look and plan ahead. Slow down! Pedestrians go first. When entering or Roundabout ahead. exiting a roundabout, yield to pedestrians at the crosswalk. Look to the left, find a safe gap, then go. Choose your destination. Start planning your route. Don’t pass vehicles in a roundabout. Remember to signal. There are two entry lanes to the roundabout. Choose the correct lane for your destination. Yield to all traffic in the roundabout including TRANSPORTATION AND pedestrians at crosswalks. ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES Remember you may have 150 Frederick Street, 7th Floor to stop! Kitchener ON N2G 4J3 Canada Phone: 519-575-4558 Flag exit signs identify Email: [email protected] street names for each leg of the roundabout. For more information check our website: www.GoRoundabout.ca Yield here to pedestrians. www.GoRoundabout.ca Updated January 2011 MOWTO HAT IS A ROUNDABOUT? HOW TO DRIVE IN A ROUNDABOUT TIPS FOR CYCLISTS A roundabout is an intersection at which ᮣ Slow down when A cyclist has two choices at a roundabout. Your all traffic circulates counterclockwise approaching a choice will depend on your degree of comfort riding roundabout. in traffic. around a centre island. ᮣ Observe lane signs. For experienced cyclists: Choose the correct ● Ride as if you were driving entry lane. a car. Yield Line ᮣ Expect pedestrians ● Merge into the travel lane Central and yield to them at before the bike lane or shoulder ends. Island all crosswalks. ● Ride in the middle of your lane; don’t hug the curb. Turning right and turning left ᮣ Wait for a gap in ● Use hand signals and signal as if you were a traffic before motorist. -

A Review of the Evidence on Cycle Track Safety Paul Schimek, Ph.D

A Review of the Evidence on Cycle Track Safety Paul Schimek, Ph.D. October 11, 2014 This memo reviews the evidence on cycle track safety. As used by bicycling advocates in North America in recent years, the terms “cycle track” or “protected bike lane” refer to a segregated path for bicyclists adjacent to an urban roadway with a curb or raised object between the bicycle path and the portion of the road used by vehicular traffic and, in some cases, also between the portion used by pedestrians. Scandinavia, Germany, and the Netherlands have the most experience with urban bicycle paths adjacent to roads, the best data, and the most comprehensive studies. In addition to a review of the best of these studies, the memo includes a review of all of the studies of cycle tracks in North America that have been conducted in the past five years. The Netherlands A 1988 Dutch study analyzed 5,763 injury crashes recorded by police between 1973 and 1977 in 14 municipalities of more than 50,000 people.1 The share of cyclists and moped users from road traffic counts was compared to the share of cyclist and moped user injuries in police reports, according to location (intersection or road segment) and according to facility type (bike lane, cycle track, or mixed traffic). The traffic counts were multiplied by road length for the segments and by the number of intersections for the intersections. For bicyclists using bicycle paths, there was a 24% reduction in risk along segments, but a 32% increase in risk in intersections, compared to bicyclists in mixed traffic (with no separate bicycle facilities). -

Traffic-Light Intersections

Give Cycling a Push Infrastructure Implementation Fact Sheet INFRASTRUCTURE/ INTERSECTIONS AND CROSSINGS TRAFFIC-LIGHT INTERSECTIONS Overview Traffic-light intersections are inherently dangerous for cyclists. However, they are indispensable when cyclists cross heavy traffic flows. Cycle-friendly design must make cyclists clearly visible, allow short and easy maneuvers and reduce waiting time, such as a right-turn bypass or an advanced stop-line. On main cycle links, separate cycle traffic light and cycle-friendly light regulation can privilege cycle flows over motorized traffic. Background and Objectives Function Intersections are equipped with a traffic control system when they need to handle large flows of motorized traffic on the busiest urban roads, often with multiple lanes. A cycle-friendly design can greatly improve safety, speed and comfort, by increasing visibility, facilitating maneuvers and reducing waiting time. Scope Traffic-light intersections are always a second-best solution for cyclists, in terms of safety. Actually, traffic light intersections with four branches are very dangerous and should be avoided in general. Dutch guidance states that roundabouts are significantly safer than traffic lights for four- branch intersections of 10,000 to 20,000 pcu/day. In practice, traffic lights are used when an intersection needs to handle large flows of motorized traffic speedily. They can handle up to 30,000 pcu/day, more than is possible with a roundabout. These will typically include at least one very busy distributor road with multiple traffic lanes (50 km/h in the built-up area, higher outside the built-up area). Often, these busy roads are also of great interest as cycle links. -

Building a Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood a Guide for Community Leaders

Building A Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood A Guide for Community Leaders Washington Area Bicyclist Association Building a Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood • Page 1 Washington Area Bicyclist Association © 2013 Suggested Citation: Building a Bicycle Friendly Neighborhood: A Guide for Community Leaders. (2013). Washington Area Bicyclist Association. Washington, D.C. The Washington Area Bicyclist Association is a nonprofit advocacy and education organization representing the metropolitan Washington area bicycling community. Reproduction of information in this guide for non-profit use is encouraged. Please use with attribution. Table of Contents Introduction and How to Use This Guide .....................................................Page 3 How Biking Projects Happen .......................................................................Page 4 Benefits of Biking .........................................................................................Page 7 The Importance of Bike Infrastructure to Get People Biking .................. Page 12 Building Community Support .................................................................... Page 20 Conclusion ...................................................................................................Page 27 Endnotes ..................................................................................................... Page 28 Appendix A: Sources Cited ......................................................................... Page 29 Appendix B: Survey Results ..................................................................... -

Designing for On-Road Bikeways

Designing for Bicyclist Safety Module B DESIGNING ON-ROAD BIKEWAYS LEARNING OUTCOMES Describe features of on-road bikeways Select design criteria for on-road bikeways in various contexts BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS BICYCLE CHARACTERISTICS Height Handlebar - 36-44 in Eye - 60 in Operating - 100 in Width Physical – 30 in Minimum operating – 48 in Preferred operating – 60 in OLDER BIKEWAY TYPES “Bike Route” “Bike Path” Neither term is clear They are all bikeways BIKEWAY NETWORK Just like roads and sidewalks, bikeways need to be part of an connected network Combine various types, including on and off-street facilities HIERARCHY OF BIKEWAYS Shared-Use Paths Separated Bike Lanes Bike Lanes Shoulders Shared Roadway Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Photo by Harvey Muller Photo by SCI Designing On-Road Bikeways SHARED ROADWAY Photo by Harvey Muller SHARED ROADWAY Most common— roads as they are Appropriate on low-volume or low-speed 85% or more of a well-connected grid SHARED LANES Unless prohibited, all roads have shared lanes No special features for: Minor roads Low volumes (< 1000 vpd) Speeds vary (urban v. rural) SHARED LANES Supplemental features Pavement markings or “sharrows” Detectors & signal timing SHARED LANE MARKING Lateral position Connect gaps in bike lanes Roadway too narrow for passing Position in intersections & transitions SHARED ROAD SIGNS Ride side-by-side? Chase bicyclist? Warning or regulation? Opposite forces? Philadelphia, PA ...and who “shares”? New Orleans, LA California SHARED ROAD SIGNS -

Cost Analysis of Bicycle Facilities: Cases from Cities in the Portland, OR Region

Cost Analysis of Bicycle Facilities: Cases from cities in the Portland, OR region FINAL DRAFT Lynn Weigand, Ph.D. Nathan McNeil, M.U.R.P. Jennifer Dill, Ph.D. June 2013 This report was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, through its Active Living Research program. Cost Analysis of Bicycle Facilities: Cases from cities in the Portland, OR region Lynn Weigand, PhD, Portland State University Nathan McNeil, MURP, Portland State University* Jennifer Dill, PhD, Portland State University *corresponding author: [email protected] Portland State University Center for Urban Studies Nohad A. Toulan School of Urban Studies & Planning PO Box 751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 June 2013 All photos, unless otherwise noted, were taken by the report authors. The authors are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their useful comments, which improved the document: Angie Cradock, ScD, MPE, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; and Kevin J. Krizek, PhD, University of Colorado Boulder. Any errors or omissions, however, are the responsibility of the authors. CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. i Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 Bike Lanes................................................................................................................................ 7 Wayfinding Signs and Pavement Markings .................................................................