The Value of Cycling’ Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cargo Bikes As a Growth Area for Bicycle Vs. Auto Trips: Exploring the Potential for Mode Substitution Behavior

Transportation Research Part F 43 (2016) 48–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part F journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trf Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: Exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior William Riggs Department of City and Regional Planning, College of Architecture and Environmental Design, California Polytechnic State University, 1 Grand Ave., San Luis Obispo, CA 93405, United States article info abstract Article history: Cargo bikes are increasing in availability in the United States. While a large body of Received 26 February 2015 research continues to investigate traditional bike transportation, cargo bikes offer the Received in revised form 15 August 2016 potential to capture trips for those that might otherwise be made by car. Data from a sur- Accepted 18 September 2016 vey of cargo bike users queried use and travel dynamics with the hypothesis that cargo and Available online 6 October 2016 e-cargo bike ownership has the potential to contribute to mode substitution behavior. From a descriptive standpoint, 68.9% of those surveyed changed their travel behavior after Keywords: purchasing a cargo bike and the number of auto trips appeared to decline by 1–2 trips per Cargo bikes day, half of the auto travel prior to ownership. Two key reasons cited for this change Bicycles Linked trips include the ability to get around with children and more gear. Regression models that Mode choice underscore this trend toward increased active transport confirm this. Based on these results, further research could include focus on overcoming weather-related/elemental barriers, which continue to be an obstacle to every day cycling, and further investigation into families modeling healthy behaviors to children with cargo bikes. -

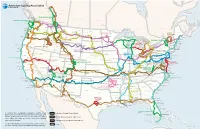

In Creating the Ever-Growing Adventure Cycling Route Network

Route Network Jasper Edmonton BRITISH COLUMBIA Jasper NP ALBERTA Banff NP Banff GREAT PARKS NORTH Calgary Vancouver 741 mi Blaine SASKATCHEWAN North Cascades NP MANITOBA WASHINGTON PARKS Anacortes Sedro Woolley 866 mi Fernie Waterton Lakes Olympic NP NP Roosville Seattle Twisp Winnipeg Mt Rainier NEW Elma Sandpoint Cut Bank NP Whitefish BRUNSWICK Astoria Spokane QUEBEC WASHINGTON Glacier Great ONTARIO NP Voyageurs Saint John Seaside Falls Wolf Point NP Thunder Bay Portland Yakima Minot Fort Peck Isle Royale Missoula Williston NOVA SCOTIA Otis Circle NORTHERN TIER NP GREEN MAINE Salem Hood Clarkston Helena NORTH DAKOTA 4,293 mi MOUNTAINS Montreal Bar Harbor River MONTANA Glendive Dickinson 380 mi Kooskia Butte Walker Yarmouth Florence Bismarck Fargo Sault Ste Marie Sisters Polaris Three Forks Theodore NORTH LAKES Acadia NP McCall Roosevelt Eugene Duluth 1,160 mi Burlington NH Bend NP Conover VT Brunswick Salmon Bozeman Mackinaw DETROIT OREGON Billings ADIRONDACK PARK North Dalbo Escanaba City ALTERNATE 395 mi Portland Stanley West Yellowstone 505 mi Haverhill Devils Tower Owen Sound Crater Lake SOUTH DAKOTA Osceola LAKE ERIE Ticonderoga Portsmouth Ashland Ketchum NM Crescent City NP Minneapolis CONNECTOR Murphy Boise Yellowstone Rapid Stillwater Traverse City Toronto Grand Teton 507 mi Orchards Boston IDAHO HOT SPRINGS NP City Pierre NEW MA Redwood NP NP Gillette Midland WISCONSIN Albany RI Mt Shasta 518 mi WYOMING Wolf Marine Ithaca YORK Arcata Jackson MINNESOTA Manitowoc Ludington City Ft. Erie Buffalo IDAHO Craters Lake Windsor Locks -

Pennine Cycleway Pennine Health Benefits of Cycling of Benefits Health Commuting Cycle

Springwood Rd). Another fast descent into the beautiful parkland brings parkland beautiful the into descent fast Another Rd). Springwood watch out for a sign turning you left down into Towneley Park (via Park Towneley into down left you turning sign a for out watch As you come into the first section on the road with houses on both sides, both on houses with road the on section first the into come you As and follow the road towards the Pike Hill area of south-east Burnley. Burnley. south-east of area Hill Pike the towards road the follow and village of Mereclough (take care on the descent). Turn right into Red Lees Rd Lees Red into right Turn descent). the on care (take Mereclough of village The Cycleway continues along the road as it drops steeply down past the past down steeply drops it as road the along continues Cycleway The distinctive shape of Pendle Hill. Hill. Pendle of shape distinctive excellent views over the surrounding countryside and across to the to across and countryside surrounding the over views excellent was used as a packhorse trail by merchants carrying woollen cloth. It offers It cloth. woollen carrying merchants by trail packhorse a as used was The Causeway dates back several centuries to when it when to centuries several back dates Causeway The past the wind farm. wind the past Bronte sisters - Withins, Stanbury and Haworth. and Stanbury Withins, - sisters Bronte The route enters Lancashire from Hebden Bridge via the Long Causeway Long the via Bridge Hebden from Lancashire enters route The east) the moor reaches across to the brooding places made famous by the by famous made places brooding the to across reaches moor the east) From Hebden Bridge via Burnley to Lake Burwain Lake to Burnley via Bridge Hebden From by a quiet attractive road at the top of Widdop Moor. -

Cycling Finding Your

Good Cycling Code Check list: Further information Cycling ✖ Do not cycle on the pavement unless it is ✔ Use designated cycle routes where possible. Other leaflets in this series: specifically designated as a shared use path Elsewhere choose quiet, minor roads avoiding major Cycling: the right bike for you finding your way (one for cyclists and walkers, and in some cases junctions. Cycling: basic bike maintenance wheelchair users or horse riders). ✔ Use the wide range of resources available to plan Cycling: in different conditions Cycling: security matters ✔ Do give way to pedestrians and other path your route. Cycling: sharing your route users when on a shared use path Useful contacts Cycling: with children ✔ Do obey the Highway Code when cycling on Sustrans Information Service tel: 0117 929 0888 or Cycling: clothes & accessories the road. www.sustrans.org.uk A full version of the ‘Good Cycling Code’ is For more copies of this leaflet or others in the series, available from Sustrans The CTC (Cyclists Touring Club) is another useful or for advice on where to cycle, including maps and resource for cyclists, offering route advice, cycle guides, contact Sustrans on 0117 929 0888 or visit www.sustrans.org.uk Maps and other resources campaigning, and third party insurance, among other benefits. See www.ctc.org.uk or call 01483 417217 for There is a huge range of maps and guides available details. Acknowledgements for cyclists. Sustrans and Bristol City Council would like to thank You may have a local cycle campaign group, who could the Government of Western Australia for guidance on Free maps be an excellent source of help and advice. -

Willy WATTS 14

VOLUME 4 BO. 3 <,JARTERLY JULY 1977 { Official Organ UNICYCLING SOCIETY OF AMERICA. Inc. c 1977 ~11 Rts Rea. Yearly Membership S5 Incl~des NeVl!lletter (4) ID Card - See Blank Pg.18 OFFICERS FELI.OW UNICYCLISTS: Due to o·trcwastances beyond our control (namely a big pile of dirt and construction lfOrk) the Southland Mall in Marion Pres. Paul Fox will not be available for our National Meet races on A.ug. 20. lttempts v.Pres. R.Tschudin to secure an alternate suita'Qle location nearby have failed. We are Sec. T. ni.ck Haines therefore planning to anit the Saturday morning races and utilize that FOUNDER M:El-!BE&S part of the day this year ror a general convention type get-together where clubs and inru.viduais can meet each other, swap ideas, and display Bernard Crandall their talents and cycles. · We still plan to hold the preliminary elimi Paul & Nancy Fox nations for the group an9- trick riding later in the day at the Catholic Peter Hangach High School parking lot·. We also have the use of the Coliseum again for Patricia Herron the Sunday afternoon final~. A pan.de is still in question and if we do Bill Jenack hold one it will be JllUCh s.horter than last year. It, is hoped that every Gordon Kruse member will make a ~ec~al-effort to attend the annual business meeting Steve McPeak Sunday rooming at th(' Hpltday Inn. We have a number of V9ry important Fr. Jas. J. Moran items on the agenda (see pag~ 14 for further infomation). -

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada Prepared by Vélo Canada Bikes for the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance pre-budget consultations Submitted August 3rd, 2018 1 Investing in cycling and active transportation: Supporting economic growth in Canada Recommendations for the Government of Canada In collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, the Assembly of First Nations and additional stakeholders, implement the following recommendations: Recommendation #1: Develop a funding stream designed to rapidly increase the development and improvement of active transportation infrastructure and related traffic calming in all Canadian municipalities and in rural areas. Recommendation #2: Establish a national-level forum to consult, share, and develop a plan for moving more people and goods by bicycle in a wide variety of Canadian settings including urban, rural and remote communities. Recommendation #3: Direct Statistics Canada to collect data that will ensure the adequate and appropriate monitoring and reporting of the prevalence, potential and safety of cycling in Canadian municipalities. Use this data to set achievable evidence-based five- and ten-year transportation mode share targets for cycling. 2 Investment in bicycling represents a vastly underexploited opportunity for economic growth in Canada. If more Canadians were able to safely use a bicycle for daily transportation, there would be significant economic benefits including: a boost to economic productivity from a healthier and more productive workforce; improved mobility and personal savings for Canadians; disadvantaged groups could more easily gain skills and access employment opportunities and there would be an increase in business and tourism revenues. Increased cycling would also help to counter the negative economic costs that motorized vehicles impose on society in the form of congestion; road casualties; physical inactivity and poor health; pollution; and the political and environmental costs of maintaining fossil fuel supplies. -

Cardiff Making Tracks Our Vision for Cycling in Cardiff

2019 Cardiff Making tracks Our vision for cycling in Cardiff Cardiff has made a lot of However, there is still much more to do to progress over the last two meet the challenges of the climate emergency, years as we have made congestion and poor air quality in a rapidly a start on our ambitious growing city. We launched our 10-year vision programme to develop for transport in January 2020, which lays out cycling infrastructure fit an ambitious plan to revolutionise transport for the 21st century city. options in Cardiff and the region. The implementation of five We have doubled the proportion of people new Cycleway routes connecting communities cycling to work over the last 10 years and to key destinations across the city is now are proposing to double this again by 2030. underway, with the first section of Cycleway 1 In order to achieve this, we will complete a on St Andrew’s Place and Senghennydd Road high-quality, safe and fully segregated cycle now completed. network by 2026, expand our successful Nextbike scheme, support schools to develop We are also improving important existing active travel plans to promote walking, scooting routes, including the Taff Trail. This has and cycling to school, and introduce a ‘Streets included the creation of Wales’ first “bicycle for Health Initiative’ to reclaim our streets as street” as part of the landmark Greener healthy spaces for everyone to enjoy. Grangetown scheme. We also want to make Cardiff a 20mph city, The take up of the Nextbike on-street cycle to normalise slower speeds and help make hire scheme has exceeded all expectations on-road cycling safer. -

Disabled People and the National Cycle Network

This information sheet is also available in large type. INFORMATION SHEET FF05 JUNE 1998 Disabled people and the National Cycle Network 1 Introduction Over 6 million people in Britain have some form of disability (1) and they often find themselves excluded from the activities that other people take for granted because their needs have not been addressed at the planning stages of key projects. In partnership with Sustrans, Local Authorities and other organisations all over the UK are developing the National Cycle Network which we believe will bring a whole range of benefits to many disabled people. This document addresses issues Smedley Toby relating to its use by disabled people. Traffic free routes benefit walkers and cyclists of all abilities and wheelchair users. We know that there are genuine concerns voiced by different users, and cyclists of all abilities and including disabled people, about wheelchair users. The routes which Definitions (3) shared use, and this document are likely to be most attractive are Where disability is referred to in this should be read in conjunction with newly constructed shared use paths information sheet, we mean: Sustrans’ Information Sheet and upgraded paths, which are Any restriction or limitation, resulting Shared Use Routes (2). described below. from an impairment, of ability to perform an activity within the range considered standard for a human being. 2 National Cycle 3 New paths Where disabled people are referred to, Network we mean: For over fifteen years, Sustrans has People who - use wheelchairs and specialised cycles been building paths free from motor - walk with difficulty, including those The National Cycle Network will be a traffic largely on disused railways with a psychological loss of function UK-wide 8,000 mile network of safe, and canal towpaths. -

Unicycle Bike Freebies and Rides for Students!

FREE UniCycle event s Bike freebies and rides for Students! FREE at your Durham Recyke Y’Bike store Shop open Wed to Sat 10.00 –17.00 www.recyke.bike l Bike lock and lights when you buy a bike*^. l Goodie bag for first 100 customers who buy a bike*. l Security marking and advice – Fri 27 Oct and Fri 1 Dec 12.00 –13.00 with Durham Constabulary. l Bike safety check (worth £10)*^. *with Durham Campus ID card from 4 Oct 2017 ^ subject to availability. Explore Bike Rides – Delivered by national charity Cycling UK who help everyone on bikes, whether you’re new to cycling, ride regularly or want to get back into it. With over 130 years’ experience we are passionate about helping more people enjoy the benefits of cycling. A series of FREE guided rides, at a gentle pace, to help you find your way around Durham and the best cycling routes to take. Booking essential. Bring your own safe working bike. Some rides include hilly sections. For more information and to book your place contact Andrew Thorp phone 07831 863770 or email [email protected]. Thurs 12 Oct Tuesday 24 Oct Saturday 4 Nov Thursday 23 Nov 5 miles 3 miles 9 miles Night Ride 3 miles 12.00 – 13.00 13.00 – 14.00 12.00 – 14.00 16.30 Meet bike stands, Meet Maiden Castle Meet St. Giles Studios, Meet St. Mary’s opposite Dept. of sports centre main Gilesgate. College main Geography. entrance. entrance. See overleaf Breeze Ride – Sat 28 Oct 14.00 – 16.00. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

This May Be the Author's Version of a Work That Was Submitted/Accepted

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Heesch, Kristiann & Sahlqvist, Shannon (2013) Key influences on motivations for utility cycling (cycling for transport to and from places). Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 24(3), pp. 227-233. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/64599/ c Copyright 2013 CSIRO This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE13062 RUNNING HEAD: Motivations for Utility Cycling Key influences on motivations for utility cycling (cycling for transport to and from places) 1 Abstract Issue addressed: Although increases in cycling in Brisbane are encouraging, bicycle mode share to work in the state of Queensland remains low. -

Coach Class the Role of the Cyclist’S Coach Is Under the Microscope

8/9 NEW YEAR NEW YOU COACH CLASS THE ROLE OF THE CYCLIST’S COACH IS UNDER THE MICROSCOPE. THEIR INFLUENCE, WISDOM, TACTICS AND MOTIVATIONAL QUALITIES CAN TRANSFORM ASPIRING AMATEURS INTO TITLE-TAKING PROFESSIONALS, BUT THEIR METHODS CAN MAKE OR BREAK AN ATHLETE. TO DISCOVER EXACTLY WHO THEY ARE AND HOW THEY MAKE A DIFFERENCE, WE WENT IN SEARCH OF THE MEN AND WOMEN IN THE SHADOWS WHO SET RIDERS ON THEIR WAY… WORDS ROB KEMP FAST-FORWARD “HAVE DIFFERENT THINKING TRAINING WORKOUTS, An exercise physiologist, sports DIFFERENT ROUTES, medicine student and coach for more than 20 years, including DIFFERENT FRIENDS – several years as a GB Cycling Team national coach, Ken Matheson ALL WILL HELP YOU pioneered remote coaching – using heart rate and power data for long- term monitoring. “I established an STAY MOTIVATED” athlete-centred cycling coaching unit which was well ahead of its Russell Burton time and, I believe, an early model for the GB Cycling Team,” he says. protein if the metabolic rate is raised – for building a ‘big engine’, fundamental One of his protégés, Dean Downing a short, easy cafe ride in good weather to good aerobic endurance.” (NFTO), believes Ken set a trend if you’re not too fatigued is ample many successful coaches now ‘active recovery’, but I would always Beware big HIITs “Interval follow. “His ability to look at the recommend one complete day a week training is usually seen as an essential bigger picture was key to his work off the bike.” component of a balanced training with me,” says Downing. “Ken programme, but such sessions should wasn’t just about establishing data, Build a big engine “A staple in only be undertaken in a well recovered recording power output, working Bradley Wiggins’ regimen is training state.