Cycling to Work: Not Only a Utilitarian Movement but Also an Embodiment of Meanings and Experiences That Constitute Crucial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cargo Bikes As a Growth Area for Bicycle Vs. Auto Trips: Exploring the Potential for Mode Substitution Behavior

Transportation Research Part F 43 (2016) 48–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part F journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/trf Cargo bikes as a growth area for bicycle vs. auto trips: Exploring the potential for mode substitution behavior William Riggs Department of City and Regional Planning, College of Architecture and Environmental Design, California Polytechnic State University, 1 Grand Ave., San Luis Obispo, CA 93405, United States article info abstract Article history: Cargo bikes are increasing in availability in the United States. While a large body of Received 26 February 2015 research continues to investigate traditional bike transportation, cargo bikes offer the Received in revised form 15 August 2016 potential to capture trips for those that might otherwise be made by car. Data from a sur- Accepted 18 September 2016 vey of cargo bike users queried use and travel dynamics with the hypothesis that cargo and Available online 6 October 2016 e-cargo bike ownership has the potential to contribute to mode substitution behavior. From a descriptive standpoint, 68.9% of those surveyed changed their travel behavior after Keywords: purchasing a cargo bike and the number of auto trips appeared to decline by 1–2 trips per Cargo bikes day, half of the auto travel prior to ownership. Two key reasons cited for this change Bicycles Linked trips include the ability to get around with children and more gear. Regression models that Mode choice underscore this trend toward increased active transport confirm this. Based on these results, further research could include focus on overcoming weather-related/elemental barriers, which continue to be an obstacle to every day cycling, and further investigation into families modeling healthy behaviors to children with cargo bikes. -

Mountain Bike Feasibility Study Discussion Paper

Primary Logo The Central Coast Council logo is a very important The logo in CMYK Blue is for universal use and a reversed The minimum size of the primary logo (blue) used should asset of our brand. version of the logo (known as the ‘white’ version of the not be less than 15mm. logo) is shown on the following page. For standard applications, this is the primary logo. Please insert this into your documents. The background where you are placing the logo should determine which version of the primary logo you use. (See usage) Filename: - Central Coast Council Blue.eps - Central Coast Council Blue.jpg - Central Coast Council Blue.png Note: - CMYK (eps) for printed materials 15mm Central Coast Council Style Guide for External Suppliers 4 MOUNTAIN BIKE FEASIB ILITY STUDY DISCUSSION PAPER Final Report April 2020 Prepared by Otium Planning Group in conjunction with World Trail. HEAD OFFICE Level 6, 60 Albert Road South Melbourne VIC 3205 p (03) 9698 7300 e [email protected] w www.otiumplanning.com.au ABN: 30 605 962 169 ACN: 605 962 169 LOCAL OFFICE Suite 1, 273 Alfred Street North North Sydney NSW 2060 Contact: Martin Lambert p 0418 151 450 e [email protected] OTIUM PLANNING GROUP OFFICES « Brisbane « Cairns « Darwin « Melbourne « New Zealand « Perth « Sydney OPG, IVG and PTA Partnership has offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing © 2020 Otium Planning Group Pty. Ltd. This document may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the terms of engagement for the commission. -

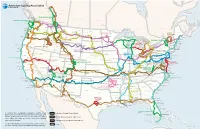

In Creating the Ever-Growing Adventure Cycling Route Network

Route Network Jasper Edmonton BRITISH COLUMBIA Jasper NP ALBERTA Banff NP Banff GREAT PARKS NORTH Calgary Vancouver 741 mi Blaine SASKATCHEWAN North Cascades NP MANITOBA WASHINGTON PARKS Anacortes Sedro Woolley 866 mi Fernie Waterton Lakes Olympic NP NP Roosville Seattle Twisp Winnipeg Mt Rainier NEW Elma Sandpoint Cut Bank NP Whitefish BRUNSWICK Astoria Spokane QUEBEC WASHINGTON Glacier Great ONTARIO NP Voyageurs Saint John Seaside Falls Wolf Point NP Thunder Bay Portland Yakima Minot Fort Peck Isle Royale Missoula Williston NOVA SCOTIA Otis Circle NORTHERN TIER NP GREEN MAINE Salem Hood Clarkston Helena NORTH DAKOTA 4,293 mi MOUNTAINS Montreal Bar Harbor River MONTANA Glendive Dickinson 380 mi Kooskia Butte Walker Yarmouth Florence Bismarck Fargo Sault Ste Marie Sisters Polaris Three Forks Theodore NORTH LAKES Acadia NP McCall Roosevelt Eugene Duluth 1,160 mi Burlington NH Bend NP Conover VT Brunswick Salmon Bozeman Mackinaw DETROIT OREGON Billings ADIRONDACK PARK North Dalbo Escanaba City ALTERNATE 395 mi Portland Stanley West Yellowstone 505 mi Haverhill Devils Tower Owen Sound Crater Lake SOUTH DAKOTA Osceola LAKE ERIE Ticonderoga Portsmouth Ashland Ketchum NM Crescent City NP Minneapolis CONNECTOR Murphy Boise Yellowstone Rapid Stillwater Traverse City Toronto Grand Teton 507 mi Orchards Boston IDAHO HOT SPRINGS NP City Pierre NEW MA Redwood NP NP Gillette Midland WISCONSIN Albany RI Mt Shasta 518 mi WYOMING Wolf Marine Ithaca YORK Arcata Jackson MINNESOTA Manitowoc Ludington City Ft. Erie Buffalo IDAHO Craters Lake Windsor Locks -

Bicycle Public Hearing Summary Report

BICYCLE PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY REPORT DALLAS AND FORT WORTH DISTRICTS IN COORDINATION WITH NORTH CENTRAL TEXAS COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS OCTOBER 2014 Bicycle Public H earing October 2014 CONTENTS 1. PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY AND ANALYSIS/RECOMMENDATIONS 2. PUBLIC HEARING COMMENT AND RESPONSE REPORT 3. PUBLIC HEARING POLL RESULTS 4. PUBLIC HEARING SURVEY RESULTS APPENDIX A. COPY OF WRITTEN COMMENTS B. COPY OF SURVEY RESULTS C. COPY OF ATTENDANCE SHEETS D. PUBLIC MEETING PHOTOS Bicycle Public H earing October 2014 1. PUBLIC HEARING SUMMARY AND ANALYSIS / RECOMMENDATIONS FOR: Texas Dept. Of Transportation (TxDOT), Dallas and Fort Worth Districts Annual Bicycle Public Hearing PURPOSE: To conduct a public hearing on transportation projects and programs that might affect bicycle use, in accordance with Title 43 of Texas Administrative Code, Subchapter D, §25.55 (b). PARTNERS: North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) Public Hearing Format The bicycle public hearing agenda is as follows: (1) Open House 5:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m (2) Welcome and Introductions 6:00 p.m. to 6:10 p.m. (a) Kathy Kleinschmidt, P.E., TxDOT Dallas District (3) Presentations 6:10 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. (a) State Bike Plan and Programs (i) Teri Kaplan – Statewide Bicycle Coordinator (b) Bicycle Policies and Projects (i) Kathy Kleinschmidt, P.E. – TxDOT Dallas District (ii) Phillip Hays, P.E. – TxDOT Fort Worth District (c) Regional Bicycle Programs and Projects (i) Karla Weaver, AICP – NCTCOG (4) Open House 7:30 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. Need and Purpose In accordance with Title 43 of Texas Administrative Code, Subchapter D, §25.55 (b) , a notice for the opportunity of a public hearing for transportation projects for bicycle use was published in the local newspapers for TxDOT’s Dallas and Fort Worth districts in April 2014. -

FHWA Bikeway Selection Guide

BIKEWAY SELECTION GUIDE FEBRUARY 2019 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave Blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED February 2019 Final Report 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. FUNDING NUMBERS Bikeway Selection Guide NA 6. AUTHORS 5b. CONTRACT NUMBER Schultheiss, Bill; Goodman, Dan; Blackburn, Lauren; DTFH61-16-D-00005 Wood, Adam; Reed, Dan; Elbech, Mary 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION VHB, 940 Main Campus Drive, Suite 500 REPORT NUMBER Raleigh, NC 27606 NA Toole Design Group, 8484 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Mobycon - North America, Durham, NC 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) 10. SPONSORING/MONITORING AND ADDRESS(ES) AGENCY REPORT NUMBER Tamara Redmon FHWA-SA-18-077 Project Manager, Office of Safety Federal Highway Administration 1200 New Jersey Avenue SE Washington DC 20590 11. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 12a. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT 12b. DISTRIBUTION CODE This document is available to the public on the FHWA website at: NA https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/ped_bike 13. ABSTRACT This document is a resource to help transportation practitioners consider and make informed decisions about trade- offs relating to the selection of bikeway types. This report highlights linkages between the bikeway selection process and the transportation planning process. This guide presents these factors and considerations in a practical process- oriented way. It draws on research where available and emphasizes engineering judgment, design flexibility, documentation, and experimentation. 14. SUBJECT TERMS 15. NUMBER OF PAGES Bike, bicycle, bikeway, multimodal, networks, 52 active transportation, low stress networks 16. PRICE CODE NA 17. SECURITY 18. SECURITY 19. SECURITY 20. -

Willy WATTS 14

VOLUME 4 BO. 3 <,JARTERLY JULY 1977 { Official Organ UNICYCLING SOCIETY OF AMERICA. Inc. c 1977 ~11 Rts Rea. Yearly Membership S5 Incl~des NeVl!lletter (4) ID Card - See Blank Pg.18 OFFICERS FELI.OW UNICYCLISTS: Due to o·trcwastances beyond our control (namely a big pile of dirt and construction lfOrk) the Southland Mall in Marion Pres. Paul Fox will not be available for our National Meet races on A.ug. 20. lttempts v.Pres. R.Tschudin to secure an alternate suita'Qle location nearby have failed. We are Sec. T. ni.ck Haines therefore planning to anit the Saturday morning races and utilize that FOUNDER M:El-!BE&S part of the day this year ror a general convention type get-together where clubs and inru.viduais can meet each other, swap ideas, and display Bernard Crandall their talents and cycles. · We still plan to hold the preliminary elimi Paul & Nancy Fox nations for the group an9- trick riding later in the day at the Catholic Peter Hangach High School parking lot·. We also have the use of the Coliseum again for Patricia Herron the Sunday afternoon final~. A pan.de is still in question and if we do Bill Jenack hold one it will be JllUCh s.horter than last year. It, is hoped that every Gordon Kruse member will make a ~ec~al-effort to attend the annual business meeting Steve McPeak Sunday rooming at th(' Hpltday Inn. We have a number of V9ry important Fr. Jas. J. Moran items on the agenda (see pag~ 14 for further infomation). -

Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region 6

Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region The Pennsylvania State University University of Maryland University of Virginia Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University West Virginia University The Pennsylvania State University The Thomas D. Larson Pennsylvania Transportation Institute Transportation Research Building University Park, PA 16802-4710 Phone: 814-863-1909 Fax: 814-865-3930 1. Report No. VT-2009-05 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. Trends and Determinants of Cycling in the Washington, DC Region 6. Performing Organization Code Virginia Tech 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Ralph Buehler with Andrea Hamre, Dan Sonenklar, and Paul Goger 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Virginia Tech, Urban Affairs and Planning, , Alexandria Center, 1021 Prince Street, Alexandria, VA 22314 11. Contract or Grant No. DTRT07-G-0003 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered US DOT Final Report, 08/2010-11/2011 Research & Innovative Technology Admin UTC Program, RDT-30 1200 New Jersey Ave., SE 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract This report analyzes cycling trends, policies, and commuting in the Washington, DC area. The analysis is divided into two parts. Part 1 focuses on cycling trends and policies in Washington (DC), Alexandria (VA), Arlington County (VA), Fairfax County (VA), Montgomery County (MD), and Prince George’s County (MD) during the last two decades. The goal is to gain a better understanding of variability and determinants of cycling within one metropolitan area. Data on bicycling trends and policies originate from official published documents, unpublished reports, site visits, and in-person, email, or phone interviews with transport planners and experts from municipal governments, regional planning agencies, and bicycling advocacy organizations. -

Bicycle Master Plan: 2012

BICYCLE MASTER PLAN: 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREPARED FOR V VISION STATEMENT VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IX CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION 1 BICYCLING IN MESA 1 THE BENEFITS OF BICYCLING 3 BICYCLE TRIP AND RIDER CHARACTERISTICS 6 BICYCLE USE IN MESA 8 PAST BICYCLE PLANNING EFFORTS 12 REGIONAL PLANNING & COORDINATION EFFORTS 15 WHY MESA NEEDS AN UPDATED BICYCLE PLAN 20 PLAN UPDATE PROCESS AND PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM 23 CHAPTER 2 - GOALS & OBJECTIVES 25 PURPOSE OF GOALS AND OBJECTIVES 25 GOAL ONE 27 GOAL TWO 28 GOAL THREE 29 GOAL FOUR 30 GOAL FIVE 31 i CHAPTER 3 - EDUCATION, ENCOURAGEMENT, AND ENFORCEMENT 33 INTRODUCTION 33 MESARIDES! 34 EDUCATION 35 ENCOURAGEMENT 38 ENFORCEMENT 42 CHAPTER 4 - BICYCLE FACILITIES AND DESIGN OPTIONS 47 INTRODUCTION 47 BASIC ELEMENTS 48 WAYFINDING 52 BICYCLE PARKING DESIGN STANDARDS 53 BICYCLE ACCESSIBILITY 58 CHAPTER 5 - MESA’S BICYCLE NETWORK 61 INTRODUCTION 61 MESA’S NETWORK OF THE FUTURE 65 DEVELOPING A RECOMMENDED FUTURE NETWORK 68 METHODOLOGY TO IDENTIFY NEEDS 72 ii CHAPTER 6 - IMPLEMENTATION, EVALUATION, AND FUNDING 101 INTRODUCTION 101 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY 103 IMPLEMENTATION CRITERIA 104 PROJECT PRIORITY RANKING 105 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROGRAM EXPANSION 122 ADDITIONAL STAFF REQUIREMENTS 124 PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT 125 SUMMARY 130 APPENDIX A - THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PLAN PROCESS 131 PURPOSE OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PLAN 131 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM AND COMMUNITY INPUT PROCESS 132 BENEFITS OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM (PIP) 132 DEVELOPMENT OF THE PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT PROGRAM (PIP) PLAN 133 MESA BICYCLE -

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada

Cycling: Supporting Economic Growth in Canada Prepared by Vélo Canada Bikes for the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance pre-budget consultations Submitted August 3rd, 2018 1 Investing in cycling and active transportation: Supporting economic growth in Canada Recommendations for the Government of Canada In collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, the Assembly of First Nations and additional stakeholders, implement the following recommendations: Recommendation #1: Develop a funding stream designed to rapidly increase the development and improvement of active transportation infrastructure and related traffic calming in all Canadian municipalities and in rural areas. Recommendation #2: Establish a national-level forum to consult, share, and develop a plan for moving more people and goods by bicycle in a wide variety of Canadian settings including urban, rural and remote communities. Recommendation #3: Direct Statistics Canada to collect data that will ensure the adequate and appropriate monitoring and reporting of the prevalence, potential and safety of cycling in Canadian municipalities. Use this data to set achievable evidence-based five- and ten-year transportation mode share targets for cycling. 2 Investment in bicycling represents a vastly underexploited opportunity for economic growth in Canada. If more Canadians were able to safely use a bicycle for daily transportation, there would be significant economic benefits including: a boost to economic productivity from a healthier and more productive workforce; improved mobility and personal savings for Canadians; disadvantaged groups could more easily gain skills and access employment opportunities and there would be an increase in business and tourism revenues. Increased cycling would also help to counter the negative economic costs that motorized vehicles impose on society in the form of congestion; road casualties; physical inactivity and poor health; pollution; and the political and environmental costs of maintaining fossil fuel supplies. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

From Counterpublics to Counterspaces: Bicyclists' Efforts to Reshape Cities

5 / 2012-13 From counterpublics to counterspaces: Bicyclists’ efforts to reshape cities Lusi Morhayim University of California, Berkeley Abstract This research examines bicyclists’ demand for the right to the city through an analysis of Critical Mass (CM) rides in San Francisco, California. The lack of investment allocated to alternative forms of transportation in the United States produces a form of social and spatial injustice because it eliminates freedom of choice not only for already disadvantaged populations but also for those who engage in everyday politics through their lifestyle choices. Ethnographic, historical, and iconographic analyses of CM rides demonstrate how these bicyclists perceive each other as a public built around shared values and lifestyles (that may broadly be defined as environmentally friendly and socially responsible). Bicyclists’ shared lifestyle defines their counter position on urban form. CM bicyclists appropriate urban streets and carry their counterdiscourses regarding street use into the public sphere. The rides strengthen bicyclists as a counterpublic, challenge automobiles’ cultural hegemony in modern urban life, subvert everyday urban experience, and allow bicyclists to create their counterspaces as they collectively ride. Keywords: Critical Mass, bicycling, counterpublic, counterspace, lifestyle politics. In San Francisco, on the last Friday of every month since 1992, rain or shine, bicyclists gather in Justin Herman Plaza starting at around six in the evening. When their numbers grow large enough for them to negotiate the right of way safely, they start the ride together. One by one, all of the bicyclists pour onto Market Street. At the very time when motorists are anxious to return home, hundreds of bicyclists circle the plaza, blocking traffic on Embarcadero in both directions. -

This May Be the Author's Version of a Work That Was Submitted/Accepted

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Heesch, Kristiann & Sahlqvist, Shannon (2013) Key influences on motivations for utility cycling (cycling for transport to and from places). Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 24(3), pp. 227-233. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/64599/ c Copyright 2013 CSIRO This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE13062 RUNNING HEAD: Motivations for Utility Cycling Key influences on motivations for utility cycling (cycling for transport to and from places) 1 Abstract Issue addressed: Although increases in cycling in Brisbane are encouraging, bicycle mode share to work in the state of Queensland remains low.