A Mass Media-Centered Approach to Teaching the Course in Family Communication. INSTITUTION National Communication Association, Annandale, VA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thornton, Arland. Reading History Sideways: the Fallacy and Enduring Inpact of The

Thornton, Arland. Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Inpact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2005. x, 312 pp.$39 By “reading history sideways,” Arland Thornton means an approach that uses information from a variety of societies at one point in time to make inferences about change over time. He attacks this method as both pervasive and pernicious, influencing scholars, past and present, as well as ordinary people and governments around the world today. A well-known demographer and sociologist, Thornton first set forth his critique to a larger audience in his 2001 presidential address to the Population Association of America (PAA). In his intellectual history of the approach, he absolves Scottish and English writers of the Enlightenment of much blame. Lacking reliable information about the distant past of their own society, authors such as John Millar, Adam Smith, and Robert Malthus seized on data pouring in from European visitors to non-European worlds as a substitute for genuine historical information. Nevertheless, they launched an enduring and fatally flawed perspective. In this book, Thornton concentrates on subjects from his areas of expertise—demographic and family studies—as he criticizes the application of the traditional-to-modern paradigm. In my opinion, Thornton’s reading of the Enlightenment founders is not so much inaccurate as it is single-minded in its emphasis and vague in its documentation. Perhaps because of his narrow, relentless focus, Thornton does not bother to cite page numbers for his sources. In my view, these writers were not principally concerned with setting forth a historical account of change over time. -

Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenKnowledge@NAU Recommended Movies and Television Programs Featuring Psychotherapy and People with Mental Disorders Timothy C. Thomason Abstract This paper provides a list of 200 feature films and five television programs that may be of special interest to counselors, psychologists and other mental health professionals. Many feature characters who portray psychoanalysts, psychiatrists, psychologists, counselors, or psychotherapists. Many of them also feature characters who have, or may have, mental disorders. In addition to their entertainment value, these videos can be seen as fictional case studies, and counselors can practice diagnosing the disorders of the characters and consider whether the treatments provided are appropriate. It can be both educational and entertaining for counselors, psychologists, and others to view films that portray psychotherapists and people with mental disorders. It should be noted that movies rarely depict either therapists or people with mental disorders in an accurate manner (Ramchandani, 2012). Most movies are made for entertainment value rather than educational value. For example, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is a wonderfully entertaining Academy Award-winning film, but it contains a highly inaccurate portrayal of electroconvulsive therapy. It can be difficult or impossible for a viewer to ascertain the disorder of characters in movies, since they are not usually realistic portrayals of people with mental disorders. Likewise, depictions of mental health professionals in the movies are usually very exaggerated or distorted, and often include behaviors that would be considered violations of professional ethical standards. Even so, psychology students and psychotherapists may find some of these movies interesting as examples of what not to do. -

On-The-Waterfront-Study-Guide

On the Waterfront Study Guide Acknowledgements Writer: Susan Bye Education Programmer Australian Centre for the Moving Image Susan’s primary role at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image is to support the teaching of film as text to secondary school students. Initially trained as an English teacher, she studied and taught film and media at La Trobe University before joining ACMI in 2009. Study Guide > On the Waterfront 2 On the Waterfront: difficult choices in an uncertain world The purpose of this guide is to provide an introduction to On the Waterfront (PG, Elia Kazan, 103 mins, USA, 1954), an overview of the commentary and debate that the film has generated and some ideas that will help you form your own interpretation of this challenging film. Studying and Interpreting On the Waterfront On the Waterfront is a film that is as problematic as it is extraordinary. It carries with it an interesting history which has, over the years, affected the way people have responded to the film. On the Waterfront encourages different and conflicting interpretations, with its controversial ending being a particular source of debate. This study guide is intended as an informative resource, providing background information and a number of different ways of thinking about the film. One of the most exciting and satisfying aspects of the film is its capacity to invite and sustain different and multifaceted interpretations. On the Waterfront focuses on life’s uncertainty and confusion, depicting both Father Barry’s dogmatic certainty and Johnny Friendly’s egotistical self-confidence as dangerously blinkered. For some viewers, Father Barry’s vision of collective action and Terry Malloy’s confused struggle to be a better man belong in two different films; however, the contrast between these two ways of looking at, and responding to, life’s challenges highlights the limitations of each of these perspectives. -

July 4, 2021 the Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Office

July 4, 2021 The Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Parish Office Pastor 6673 West Chatfield Avenue • Littleton, CO 80128 Rev. John Paul Leyba www.sfcparish.org Parochial Vicars 303-979-7688 Parish Office Rev. Israel Gonsalves, O.C.D. Open: Monday-Friday, 8:30am-5:00pm Rev. Ron Sequeira, O.C.D. (closed 12:00 noon-1:00pm daily) 303-979-7688 Voice mail access after 5:00pm 303-953-7777 Youth Office (Jr. & Sr. High, Young Adult) Deacons 303-972-8566 Fax Line Rev. Mr. Chet Ubowski 303-979-7688 SACRAMENTAL EMERGENCIES Rev. Mr. Marc Nestorick 24 hrs/day Rev. Mr. Brian Kerby St. Frances303-953-7770 Cabrini Weather/Emergency Hotline Rev. Mr. Spencer Thornber (for schedule changes due to inclement Rev. Mr. Paul Grimm (retired) weather/emergency situations) Rev. Mr. Witold Engel (retired) Welcome to Our Parish! We are glad you are here! If you are a visitor and would like to join our parish family, please pick up a registration form in the gathering space, visit the parish office during the week or you may visit our website to register. Sacramental Information Mass Schedule Infant Baptism: Please contact Deacon Chet at 303-953-7783. Weekend ... Saturday (Anticipatory) 4:15 pm; Sunday 7:15, 9:15, 11:15am & 5:15pm Marriage Preparation: Please contact Trudy at 303-953-7769 at Weekday .............. Monday-Friday 9:00 am; least 9-12 months prior to your wedding to make arrangements. Mon., Tues., Thurs., Fri. 6:30am RCIA: Interested in becoming Catholic or questions about the faith? First Saturday .............................. 10:00am Call Deacon Chet at 303-953-7783. -

Films Winning 4 Or More Awards Without Winning Best Picture

FILMS WINNING 4 OR MORE AWARDS WITHOUT WINNING BEST PICTURE Best Picture winner indicated by brackets Highlighted film titles were not nominated in the Best Picture category [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] 8 AWARDS Cabaret, Allied Artists, 1972. [The Godfather] 7 AWARDS Gravity, Warner Bros., 2013. [12 Years a Slave] 6 AWARDS A Place in the Sun, Paramount, 1951. [An American in Paris] Star Wars, 20th Century-Fox, 1977 (plus 1 Special Achievement Award). [Annie Hall] Mad Max: Fury Road, Warner Bros., 2015 [Spotlight] 5 AWARDS Wilson, 20th Century-Fox, 1944. [Going My Way] The Bad and the Beautiful, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] The King and I, 20th Century-Fox, 1956. [Around the World in 80 Days] Mary Poppins, Buena Vista Distribution Company, 1964. [My Fair Lady] Doctor Zhivago, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1965. [The Sound of Music] Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Warner Bros., 1966. [A Man for All Seasons] Saving Private Ryan, DreamWorks, 1998. [Shakespeare in Love] The Aviator, Miramax, Initial Entertainment Group and Warner Bros., 2004. [Million Dollar Baby] Hugo, Paramount, 2011. [The Artist] 4 AWARDS The Informer, RKO Radio, 1935. [Mutiny on the Bounty] Anthony Adverse, Warner Bros., 1936. [The Great Ziegfeld] The Song of Bernadette, 20th Century-Fox, 1943. [Casablanca] The Heiress, Paramount, 1949. [All the King’s Men] A Streetcar Named Desire, Warner Bros., 1951. [An American in Paris] High Noon, United Artists, 1952. [The Greatest Show on Earth] Sayonara, Warner Bros., 1957. [The Bridge on the River Kwai] Spartacus, Universal-International, 1960. [The Apartment] Cleopatra, 20th Century-Fox, 1963. -

The Return of the 1950S Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980S

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s Chris Steve Maltezos University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Maltezos, Chris Steve, "The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s by Chris Maltezos A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 4, 2011 Keywords: Intergenerational Relationships, Father Figure, insular sphere, mother, single-parent household Copyright © 2011, Chris Maltezos Dedication Much thanks to all my family and friends who supported me through the creative process. I appreciate your good wishes and continued love. I couldn’t have done this without any of you! Acknowledgements I’d like to first and foremost would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. -

Families-On-Facebook.Pdf

Families on Facebook Moira Burke, Lada A. Adamic, and Karyn Marciniak {mburke, ladamic, karyn}@fb.com Facebook Menlo Park, CA 94025 Abstract and when), mutual friends, and how communication varies This descriptive study of millions of US Facebook users with the age of the child and geographic distance. We find documents "friending" and communication patterns, explor- that nearly 40% of Facebook users have either a parent or ing parent-child relationships across a variety of life stages child on the site, and that communication frequency does and gender combinations. Using statistical techniques on not decrease with geographic distance, unlike previous re- 400,000 posts and comments, we identify differences in how parents talk to their children (giving advice, affection, search on family communication. and reminders to call) compared to their other friends, and Using a wealth of anonymized, aggregated intra-family how they address their adult sons and daughters (talking communication data, we also paint a detailed picture of about grandchildren and health concerns, and linguistically what parents and their children talk about on Facebook. treating them like peers) compared to their teenage children. Consistent with offline research, we see mothers doling out Parents and children have 20-30 mutual friends on the site, 19% of whom are relatives. Unlike previous findings on affection and reminding their kids to call, and fathers talk- family communication, interaction frequency on Facebook ing about specific shared interests, such as sports and poli- does not decrease with geographic distance. tics. Grandchildren and food are common topics. We also identify a linguistic shift when parents talk to their grown- up children compared to how they talk to teens, treating Introduction their 40 year-old children much like they do their other Facebook’s widespread adoption by users of all ages cou- adult friends. -

Film Streams Programming Calendar Westerns

Film Streams Programming Calendar The Ruth Sokolof Theater . July – September 2009 v3.1 Urban Cowboy 1980 Copyright: Paramount Pictures/Photofest Westerns July 3 – August 27, 2009 Rio Bravo 1959 The Naked Spur 1953 Red River 1948 Pat Garrett & High Noon 1952 Billy the Kid 1973 Shane 1953 McCabe and Mrs. Miller 1971 The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance 1962 Unforgiven 1992 The Magnificent Seven 1960 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward The Good, the Bad Robert Ford 2007 and the Ugly 1966 Johnny Guitar 1954 There’s no movie genre more patently “American” True Westerns —the visually breathtaking work of genre auteurs like Howard than the Western, and perhaps none more Hawks, John Ford, Sam Peckinpah, and Sergio Leone—are more like Greek generally misunderstood. Squeaky-clean heroes mythology set to an open range, where the difference between “good” and versus categorical evil-doers? Not so much. “bad” is often slim and sometimes none. If we’re missing one of your favorites here, rest assured this is a first installment of an ongoing salute to this most epic of all genres: the Western. See reverse side for full calendar of films and dates. Debra Winger August 28 – October 1, 2009 A Dangerous Woman 1993 Cannery Row 1982 The Sheltering Sky 1990 Shadowlands 1993 Terms of Endearment 1983 Big Bad Love 2001 Urban Cowboy 1980 Mike’s Murder 1984 Copyright: Paramount Pictures/Photofest From her stunning breakthrough in 1980’s URBAN nominations to her credit. We are incredibly honored to have her as our COWBOY to her critically acclaimed performance special guest for Feature 2009 (more details on the reverse side), and for in 2008’s RACHEL GETTING MARRIED, Debra her help in curating this special repertory series featuring eight of her own Winger is widely regarded as one of the finest films—including TERMS OF ENDEARMENT, the Oscar-winning picture actresses in contemporary cinema, with more that first brought her to Nebraska a quarter century ago. -

Needs of a Person Who Suffered from Autism As Portrayed in Winston Groom’S Forrest Gump

NEEDS OF A PERSON WHO SUFFERED FROM AUTISM AS PORTRAYED IN WINSTON GROOM’S FORREST GUMP A THESIS BY: TEGUH PERDANA DAMANIK REG.NO. 140705010 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA NEEDS OF A PERSON WHO SUFFERED FROM AUTISM AS PORTRAYED IN WINSTON GROOM’S FORREST GUMP A THESIS BY TEGUH PERDANA DAMANIK REG. NO. 140705010 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Drs. Parlindungan Purba, M.Hum. Riko Andika Rahmat Pohan, S.S., M.Hum. NIP. 19630216 198903 1 003 NIP. 19580517198503 1 003 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan i n partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2018 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head Secretary Prof. T. Silvana Sinar, M. A., Ph. D Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph. D. NIP. 19540916 198003 2 003 NIP. 19750209 200812 1 002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara, Medan. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on 15th August 2018 Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Ordinary People Press

ORDINARY PEOPLE Writer/director Dr. Jennifer Rutherford Producer Martha Ansara Film Australia Executive Producer Stefan Moore A FILM AUSTRALIA NATIONAL INTEREST PROGRAM PRODUCED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE AUSTRALIAN FILM COMMISSION, THE NEW SOUTH WALES FILM AND TELEVISION OFFICE AND THE AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION. © Film Australia ORDINARY PEOPLE SYNOPSIS Far right and anti-immigration politics are on the rise worldwide. In Australia, as in many other western countries, a new political force is drawing on the discontent of those who feel excluded from the promised benefits of globalisation. Rejecting the new world order and its transformation of their economies and cultures, these people are convinced that traditional political parties no longer represent them or their interests. They are desperate to make their voice heard. For Colene Hughes and her supporters, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party initially appears to offer a solution. It seems to promise true democracy, a way of knocking the country back into shape - giving people like them some power again. However, over time, their belief in the moral rightness of One Nation is confronted by the realities of the party’s internal politics. Once Colene starts to question the authoritarian control of the party’s executive members, the gloves come off. At the annual general meeting, the two forces collide. This revealing documentary follows Colene through two years and two election campaigns as a One Nation candidate in Ipswich, Queensland, heartland of One Nation. It travels with her on the campaign trail as her idealistic fervour slowly turns to disillusionment. It also gives the viewer an unparalleled look at One Nation - from the inside. -

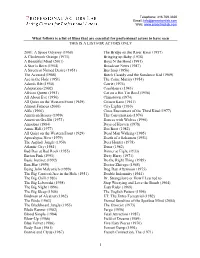

1 What Follows Is a List of Films That Are

Telephone: 416.769.3320 Email: [email protected] Web: www.proactroslab.com What follows is a list of films that are essential for professional actors to have seen THIS IS A LIST FOR ACTORS ONLY 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) A Clockwork Orange (1971) Bringing up Baby (1938) A Beautiful Mind (2001) Boyz N the Hood (1991) A Star is Born (1954) Broadcast News (1987) A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) Bus Stop (1956) The Accused (1988) Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) Ace in the Hole (1951) The Caine Mutiny (1954) Adam's Rib (1950) Carrie (1976) Adaptation (2002) Casablanca (1943) African Queen (1951) Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) All About Eve (1950) Chinatown (1974) All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) Citizen Kane (1941) Almost Famous (2000) City Lights (1930) Alfie (1966) Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) American Beauty (1999) The Conversation (1974) American Graffiti (1973) Dances with Wolves (1990) Amadeus (1984) Days of Heaven (1978) Annie Hall (1977) Das Boot (1982) All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) Dead Man Walking (1995) Apocalypse Now (1979) Death of a Salesman (1951) The Asphalt Jungle (1950) Deer Hunter (1978) Atlantic City (1981) Diner (1982) Bad Day at Bad Rock (1955) Dinner at Eight (1933) Barton Fink (1991) Dirty Harry (1971) Basic Instinct (1992) Do the Right Thing (1989) Ben-Hur (1959) Doctor Zhivago (1965) Being John Malcovich (1999) Dog Day Afternoon (1975) The Big Carnival/Ace in the Hole (1951) Double Indemnity (1944) The Big Chill (1983) Dr.