ST CECILIA's HALL Niddry Street, Edinburgh Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH

UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus Undergraduate 2012 Entry 2012 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry www.ed.ac.uk EDINB E56 UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 3 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 1 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Welcome to the University of Edinburgh We’ve been influencing the world since 1583. We can help influence your future. Follow us on www.twitter.com/UniofEdinburgh or watch us on www.youtube.com/user/EdinburghUniversity UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 3 The University of Edinburgh Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry Welcome www.ed.ac.uk 3 Welcome Welcome Contents Contents Why choose the University of Edinburgh?..... 4 Humanities & Our story.....................................................................5 An education for life....................................................6 Social Science Edinburgh College of Art.............................................8 pages 36–127 Learning resources...................................................... 9 Supporting you..........................................................10 Social life...................................................................12 Medicine & A city for adventure.................................................. 14 Veterinary Medicine Active life.................................................................. 16 Accommodation....................................................... 20 pages 128–143 Visiting the University............................................... -

Hoock Empires Bibliography

Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination: Politics, War, and the Arts in the British World, 1750-1850 (London: Profile Books, 2010). ISBN 978 1 86197. Bibliography For reasons of space, a bibliography could not be included in the book. This bibliography is divided into two main parts: I. Archives consulted (1) for a range of chapters, and (2) for particular chapters. [pp. 2-8] II. Printed primary and secondary materials cited in the endnotes. This section is structured according to the chapter plan of Empires of the Imagination, the better to provide guidance to further reading in specific areas. To minimise repetition, I have integrated the bibliographies of chapters within each sections (see the breakdown below, p. 9) [pp. 9-55]. Holger Hoock, Empires of the Imagination (London, 2010). Bibliography © Copyright Holger Hoock 2009. I. ARCHIVES 1. Archives Consulted for a Range of Chapters a. State Papers The National Archives, Kew [TNA]. Series that have been consulted extensively appear in ( ). ADM Admiralty (1; 7; 51; 53; 352) CO Colonial Office (5; 318-19) FO Foreign Office (24; 78; 91; 366; 371; 566/449) HO Home Office (5; 44) LC Lord Chamberlain (1; 2; 5) PC Privy Council T Treasury (1; 27; 29) WORK Office of Works (3; 4; 6; 19; 21; 24; 36; 38; 40-41; 51) PRO 30/8 Pitt Correspondence PRO 61/54, 62, 83, 110, 151, 155 Royal Proclamations b. Art Institutions Royal Academy of Arts, London Council Minutes, vols. I-VIII (1768-1838) General Assembly Minutes, vols. I – IV (1768-1841) Royal Institute of British Architects, London COC Charles Robert Cockerell, correspondence, diaries and papers, 1806-62 MyFam Robert Mylne, correspondence, diaries, and papers, 1762-1810 Victoria & Albert Museum, National Art Library, London R.C. -

Edit Summer 2003

VOLUME THREE ISSUE TWO SUMMER 2003 EEDDiTiT TINKER TAILOR DOCTOR LAWYER EXCELLENCE PARTICIPATION WEALTH POVERTY INTELLIGENCE ADVANTAGE DISADVANTAGE EQUALITY LEADING THE WAY TO HIGHER EDUCATION Why wider access is essential for universities E D iTcontents The University of Edinburgh Magazine volume three issue two summer 2003 16 L 12 20 22 COVER STORIES 12 WIDENING PARTICIPATION Ruth Wishart’s forthright view of the debate 39 GENERAL COUNCIL The latest news in the Billet FEATURES 22 IMMACULATE COLLECTIONS Prof Duncan Macmillan looks at the University’s Special Collections 10 MAKING IT HAPPEN How a boy from Gorgie became Chairman of ICI REGULARS 04 EditEd News in and around the University publisher Communications & Public Affairs, 20 ExhibitEd Art at the Talbot Rice Gallery The University of Edinburgh Centre, 36 Letters As the new Rector is installed, a look at Rectors past 7-11 Nicolson Street, 27 InformEd Alumni interactions, past, present and future Edinburgh EH8 9BE World Service Alumni news from Auchtermuchty to Adelaide, or almost editor Clare Shaw 30 [email protected] design Neil Dalgleish at Hillside WELCOME TO the summer issue of EDiT. It’s an honour – and not a little daunting – to take over the editing of such [email protected] a successful magazine from Anne McKelvie, who founded the magazine, and Ray Footman, who ably took over the reins photography after Anne’s death. Tricia Malley, Ross Gillespie at broad dayligh 0131 477 9211 Enclosed with this issue you’ll find a brief survey. Please do take a couple of minutes to fill it in and return it. -

Altea Gallery

Front cover: item 32 Back cover: item 16 Altea Gallery Limited Terms and Conditions: 35 Saint George Street London W1S 2FN Each item is in good condition unless otherwise noted in the description, allowing for the usual minor imperfections. Tel: + 44 (0)20 7491 0010 Measurements are expressed in millimeters and are taken to [email protected] the plate-mark unless stated, height by width. www.alteagallery.com (100 mm = approx. 4 inches) Company Registration No. 7952137 All items are offered subject to prior sale, orders are dealt Opening Times with in order of receipt. Monday - Friday: 10.00 - 18.00 All goods remain the property of Altea Gallery Limited Saturday: 10.00 - 16.00 until payment has been received in full. Catalogue Compiled by Massimo De Martini and Miles Baynton-Williams To read this catalogue we recommend setting Acrobat Reader to a Page Display of Two Page Scrolling Photography by Louie Fascioli Published by Altea Gallery Ltd Copyright © Altea Gallery Ltd We have compiled our e-catalogue for 2019's Antiquarian Booksellers' Association Fair in two sections to reflect this year's theme, which is Firsts The catalogue starts with some landmarks in printing history, followed by a selection of highlights of the maps and books we are bringing to the fair. This year the fair will be opened by Stephen Fry. Entry on that day is £20 but please let us know if you would like admission tickets More details https://www.firstslondon.com On the same weekend we are also exhibiting at the London Map Fair at The Royal Geographical Society Kensington Gore (opposite the Albert Memorial) Saturday 8th ‐ Sunday 9th June Free admission More details https://www.londonmapfairs.com/ If you are intending to visit us at either fair please let us know in advance so we can ensure we bring appropriate material. -

SGSSS Summer School 2018

SGSSS Summer School 2018 PROGRAMME Tuesday 19th June 08.45-09.45 Registration & welcome at David Hume Tower reception (Location map attached) 10.00-13.00 Workshops (class lists and room numbers will be posted in the reception area each morning) 13.00-14.00 Lunch (provided each day in the Lower Ground area between David Hume Tower and 50 George Square, next to the café) 14.00-15.30 Workshops 15.30-15.50 Refreshment break (provided each day as per lunch location) 15.50-17.00 Workshops 17.00-20.00 Welcome wine reception at 56 North (Directions attached – 3 mins walk from David Hume Tower) Wednesday 20th June 08.45-09.45 Registration & welcome at David Hume Tower reception (Location map attached) 10.00-13.00 Workshops (class lists and room numbers will be posted in the reception area each morning) 13.00-14.00 Lunch (provided each day in the Lower Ground area between David Hume Tower and 50 George Square, next to the café) 14.00-15.30 Workshops 15.30-15.50 Refreshment break (provided each day as per lunch location) 15.50-17.00 Workshops 18.00-22.00 Pub Quiz night with food & drinks – Cabaret Voltaire, Blair Street (Location map attached – 10 minute walk from David Hume Tower) Thursday 21st June 08.45-09.45 Registration & welcome at David Hume Tower reception (Location map attached) 10.00-13.00 Workshops (class lists and room numbers will be posted in the reception area each morning) 13.00-14.00 Lunch (provided each day in the Lower Ground area between David Hume Tower and 50 George Square, next to the café) 14.00-15.30 Workshops 15.30-15.50 Refreshment break (provided each day as per lunch location) 15.50-17.00 Workshops Summer School ends KEY LOCATIONS & INFO ON CLAIMIMG EXPENSES LOCATION OF SUMMER SCHOOL - DAVID HUME TOWER (UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH CENTRAL CAMPUS, EH8 9JX) *If you experience mobility issues, please inform SGSSS staff prior to arrival and assistance will be provided. -

Persons Index

Architectural History Vol. 1-46 INDEX OF PERSONS Note: A list of architects and others known to have used Coade stone is included in 28 91-2n.2. Membership of this list is indicated below by [c] following the name and profession. A list of architects working in Leeds between 1800 & 1850 is included in 38 188; these architects are marked by [L]. A table of architects attending meetings in 1834 to establish the Institute of British Architects appears on 39 79: these architects are marked by [I]. A list of honorary & corresponding members of the IBA is given on 39 100-01; these members are marked by [H]. A list of published country-house inventories between 1488 & 1644 is given in 41 24-8; owners, testators &c are marked below with [inv] and are listed separately in the Index of Topics. A Aalto, Alvar (architect), 39 189, 192; Turku, Turun Sanomat, 39 126 Abadie, Paul (architect & vandal), 46 195, 224n.64; Angoulême, cath. (rest.), 46 223nn.61-2, Hôtel de Ville, 46 223n.61-2, St Pierre (rest.), 46 224n.63; Cahors cath (rest.), 46 224n.63; Périgueux, St Front (rest.), 46 192, 198, 224n.64 Abbey, Edwin (painter), 34 208 Abbott, John I (stuccoist), 41 49 Abbott, John II (stuccoist): ‘The Sources of John Abbott’s Pattern Book’ (Bath), 41 49-66* Abdallah, Emir of Transjordan, 43 289 Abell, Thornton (architect), 33 173 Abercorn, 8th Earl of (of Duddingston), 29 181; Lady (of Cavendish Sq, London), 37 72 Abercrombie, Sir Patrick (town planner & teacher), 24 104-5, 30 156, 34 209, 46 284, 286-8; professor of town planning, Univ. -

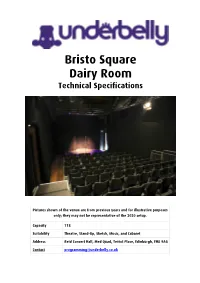

Bristo Square Dairy Room Technical Specifications

Bristo Square Dairy Room Technical Specifications Pictures shown of the venue are from previous years and for illustrative purposes only; they may not be representative of the 2020 setup. Capacity 118 Suitability Theatre, Stand-Up, Sketch, Music, and Cabaret Address Reid Concert Hall, Med Quad, Teviot Place, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG Contact [email protected] Dairy Room is a space that boasts high ceilings and a feel of grandeur. This is an end-on space with a raised stage, fully raked seating and great sightlines. Within the bustling hub of McEwan Hall and Bristo Square, Dairy Room is ideal for stand- up comedy and small to mid-scale theatre. The stage measures W3.6m x D2.4m and is open on all sides, elevated 200mm from the floor. The upstage wall is a row of Stage and flats with a doorway in the middle to enter through. There will Seating be a small space behind the flats on stage right for props. The audience seating consists of a 12-row seating rake with a capacity of 118 people. The venue will provide: - two area front light: ETC colour source profiles - back light: LED Rush PAR Zooms Lighting - lighting desk: Zero88 FLX - stage power: 2 x 13A single phase supply Companies may be able to add specials to the rig, but these should be discussed with us in advance. A house system consisting of: - 2 x d&b Q7 Point Source - 1 x d&b Q-Sub Sound - 2 x passive DI box - 1 x mini jack connection for laptop playback - 2 x microphones, SM58 - 2 x microphone boom stands No video hardware is provided as standard, however in previous years companies have hired in a large flat-screen TV Video on a wheeled base as an alternative to projection as there is no capacity to rig a projector. -

Guide to the Dowd Harpsichord Collection

Guide to the Dowd Harpsichord Collection NMAH.AC.0593 Alison Oswald January 2012 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: William Dowd (Boston Office), 1958-1993................................................ 4 Series 2 : General Files, 1949-1993........................................................................ 8 Series 3 : Drawings and Design Notes, 1952 - 1990............................................. 17 Series 4 : Suppliers/Services, 1958 - 1988........................................................... -

II IAML Annual Conference

IAML Annual Conference Edinburgh II 6 - I I August 2000 International Association of Music Libraries,Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Association Internationale des Bibliothèques,Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren (IVBM) Contents 3 Introduction: English 13 Einleitung: Deutsch 23 Introduction: Français 36 Conference Programme 51 IAML Directory 54 IAML(UK) Branch 59 Sponsors IAML Annual Conference The University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, Scotland 6 - I I August 2000 International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Association Internationale des Bibliothèques,Archives et Centres de Documentation Musicaux (AIBM) Internationale Vereinigung der Musikbibliotheken, Musikarchive und Musikdokumentationszentren (IVBM) oto: John Batten Without the availability of music libraries, I would never have got to know musical scores. They are absolutely essential for the furtherance of musical knowledge and enjoyment. It is with great pleasure therefore that I lend my support to the prestigious conference of IAML which is being hosted by the United Kingdom Branch in Edinburgh. I am delighted as its official patron to commend the 2000 IAML international conference of music librarians' Sir Peter Maxwell Davies Patron: IAML2000 5 II Welcome to Edinburgh Contents We have great pleasure in welcoming you to join us in the 6 Conference Information beautiful city of Edinburgh for the 2000 IAML Conference. 7 Social Programme Events during the week will take place in some of the 36 Conference Programme city's magnificent buildings and Wednesday afternoon tours 5I IAML Directory are based on the rich history of Scotland.The Conference 54 IAML(UK) Branch sessions as usual provide a wide range of information to 59 Sponsors interest librarians from all kinds of library; music is an international language and we can all learn from the experiences of colleagues. -

Easter Bush Campus Edinburgh Bioquarter the University in the City

The University in the city Easter Bush Campus Edinburgh BioQuarter 14 Arcadia Nursery 12 Greenwood Building, including the 4 Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic Aquaculture Facility 15 Bumstead Building 3 Chancellor’s Building Hospital for Small Animals 13 Campus Service Centre 2 1 Edinburgh Imaging Facility QMRI R(D)SVS William Dick Building 10 Charnock Bradley Building, including 1 5 Edinburgh Imaging Facility RIE (entrance) Riddell-Swan Veterinary Cancer Centre the Roslin Innovation Centre 3 2 Queen’s Medical Research Institute Roslin Institute Building 7 Equine Diagnostic, Surgical and 11 6 Scottish Centre for Regenerative Medicine Critical Care Unit 5 Scintigraphy and Exotic Animal Unit 6 Equine Hospital 8 Sir Alexander Robertson Building Public bus 4 Farm Animal Hospital DP Disabled permit parking P Public parking 9 Farm Animal Practice and Middle Wing P Permit parking Public bus The University Central Area The University of Edinburgh is a charitable body, registered in Scotland, with registration number SC005336. in Scotland, with registration registered The University of Edinburgh is a charitable body, ). 44 Adam House 48 ECCI 25 Hope Park Square 3 N-E Studio Building 74 Richard Verney Health Centre 38 Alison House 5 Edinburgh Dental 16 Hugh Robson Building 65 New College Institute 1–7 Roxburgh Street 31 Appleton Tower 4 Hunter Building 41 Old College and 52 Evolution House Talbot Rice Gallery Simon Laurie House 67 Argyle House 1 46 9 Infirmary Street 61 5 Forrest Hill Old Infirmary Building St Cecilia’s Hall 72 Bayes Centre -

![The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0899/the-mylne-family-microform-master-masons-architects-engineers-their-professional-career-1481-1876-1410899.webp)

The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876

THE MYLNE FAMILY. MASTER MASONS, ARCHITECTS, ENGINEERS THEIR PROFESSIONAL CAREER 1481-1876. PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION BY ROBERT W. MYLNE, C.E., F.R.S., F.S.A., F.G.S., F.S.A Scot PEL, INST. BRIT. ARCH LONDON 187 JOHN MYLNE, MASTER MASON ANDMASTER OF THE LODGE OF SCONE. {area 1640—45.) Jfyotn an original drawing in tliepossession of W. F. Watson, Esq., Edinburgh. C%*l*\ fA^ CONTENTS. PREFACE. " REPRINT FROM ARTICLEIN DICTIONARYOF ARCHITECTURE.^' 1876. REGISTER 07 ABMB—LTONOFFICE—SCOTLAND,1672. BEPBIKT FBOH '-' HISTOBT OF THKLODGE OF EDINBURGH," 1873. CONTRACT BT THE MASTER MASONS OF THE LODGE OF SCONE AND PERTH, 1658. APPENDIX. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE, 1567—1604. CONTRACT WITH GEORGE THOMSON AND JOHN MTLNE, MASONS, TO MAKE ADDITIONS TO LORD BANNTAYNE'S HOUSE AT NEWTTLE. NEAR DUNDEE, 1589. — EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF EDINBURGH, 1616 17. CONTRACT BETWIXT JOHN MTLNE,AND LORD SCONE TO BUILD A CHURCH AT FALKLAND,1620. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE AND ABERDEEN, 1622—27. EXTRACT FROM THE CHAMBEBLAIn'b ACCOUNTS OF THE EABL OF PERTH, 1629. GRANT TOJOHN MTLNEOF THE OFFICE OF PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON TO THEKING,1631. EXTRACTS FBOM THE BUBGH BOOKS OF KIBCALDT AND DUNDEE, 1643—51. GRANT TO JOHN MTLNE, TOUNGER, KING'S PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON> OF THE OFFICE OF CAPTAIN AND MASTER OF PIONEERS AND PRINCIPAL MASTER GUNNER OF ALLSCOTLAND,1646. CONTRACT WITHJOHN MTLNEAND GEORGE 2ND EABL 09 PANMUBE TO BUILDPANMURE HOUSE, ADJACENT TO THE ANCIENT MANSION AT BOWBCHIN, NEAR DUNDEE, 1666. BOTAL WARRANT CONCERNING THE FINISHING OF THE PALACE OF HOLTROOD, 21 FEBRUARY,1676. -

Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise

PMSA NRP: Work Record Ref: EDIN0721 03-Jun-11 © PMSA RAC Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise 773 Carver: Unknown Town or Village Parish Local Govt District County Edinburgh Edinburgh NPA The City of Edinburgh Council Lothian Area in town: Old Town Road: Palace of Holyroodhouse Location: North-west end, between 1st floor windows, of Palace of Holyroodhouse A to Z Ref: OS Ref: Postcode: Previously at: Setting: On building SubType: Public access with entrance fee Commissioned by: Year of Installation: 1906 Details: Design Category: Animal Category: Architectural Category: Commemorative Category: Heraldic Category: Sculptural Class Type: Coat of Arms SubType: Define in freetext of Mary of Guise Subject Non Figurative SubType: Full Length Part(s) of work Material(s) Dimensions > Whole Stone Work is: Extant Listing Status: I Custodian/Owner: Royal Household Condition Report Overall Condition: Good Risk Assessment: No Known Risk Surface Character: Comment No damage Vandalism: Comment None Inscriptions: At base of panel (raised letters): M. R Signatures: None Physical Panel carved in high relief. An eagle with a crown around its neck stands in profile (facing S.) holding a Description: diamond-shaped shield in its left foot. The shield is quartered with a small shield at its centre. Behind the eagle are lilies and below are the initials M. R flanked by fleurs de lis Person or event Mary of Guise commemorated: History of Commission : Exhibitions: Related Works: Legal Precedents: References: J. Gifford, C. McWilliam, D. Walker and C. Wilson,