JR 32 BOOK.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32/: –33 © 2005 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural The supernatural powers of Japanese poetry are widely documented in the lit- erature of Heian and medieval Japan. Twentieth-century scholars have tended to follow Orikuchi Shinobu in interpreting and discussing miraculous verses in terms of ancient (arguably pre-Buddhist and pre-historical) beliefs in koto- dama 言霊, “the magic spirit power of special words.” In this paper, I argue for the application of a more contemporaneous hermeneutical approach to the miraculous poem-stories of late-Heian and medieval Japan: thirteenth- century Japanese “dharani theory,” according to which Japanese poetry is capable of supernatural effects because, as the dharani of Japan, it contains “reason” or “truth” (kotowari) in a semantic superabundance. In the first sec- tion of this article I discuss “dharani theory” as it is articulated in a number of Kamakura- and Muromachi-period sources; in the second, I apply that the- ory to several Heian and medieval rainmaking poem-tales; and in the third, I argue for a possible connection between the magico-religious technology of Indian “Truth Acts” (saccakiriyā, satyakriyā), imported to Japan in various sutras and sutra commentaries, and some of the miraculous poems of the late- Heian and medieval periods. keywords: waka – dharani – kotodama – katoku setsuwa – rainmaking – Truth Act – saccakiriyā, satyakriyā R. Keller Kimbrough is an Assistant Professor of Japanese at Colby College. In the 2005– 2006 academic year, he will be a Visiting Research Fellow at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. -

Visualizing the Classics: Intellectual Networks and Cultural Nostalgia

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/58771 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Kok, D.P. Title: Visualizing the classics : reading surimono and ky ka books as social and cultural history Issue Date: 2017-10-10 ō Chapter 5: Visualizing the classics: Intellectual networks and cultural nostalgia 5.1 Introduction This chapter investigates how kyōka poets acquired their knowledge of classical literature, discusses the way in which poets and illustrators visualized literature in their projects, and reflects on what their motivations were for referring to specific elements in cultural history. Shunman’s kokugaku connections have been elucidated by Tanaka, and kokugaku influences in two surimono series that Shunman designed in the first half of the 1810s have been researched by Carpenter.302 My investigation continues on their approach by tracing how other major kyōka poets and surimono designers were connected to intellectual networks of their time; in particular to scholars of the classical texts that inspired literary surimono series. Moreover, textual information in the surimono is matched to contemporaneous scholarship. Did knowledge of classical literature enter kyōka society via printed exegetical texts in commercial editions, or are ties to scholars generally so close that surimono creators had access to such knowledge already before the general public did? How did kyōka poets relate to the ideological underpinnings of the kokugaku movement? And is there any relation between birth class and the influx of cultural knowledge detectable in kyōka society? Answering these questions will clarify where surimono creators gained their understanding of the classical texts they visualized, and what role each of these creators played. -

Rape in the Tale of Genji

SWEAT, TEARS AND NIGHTMARES: TEXTUAL REPRESENTATIONS OF SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN HEIAN AND KAMAKURA MONOGATARI by OTILIA CLARA MILUTIN B.A., The University of Bucharest, 2003 M.A., The University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2008 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 ©Otilia Clara Milutin 2015 Abstract Readers and scholars of monogatari—court tales written between the ninth and the early twelfth century (during the Heian and Kamakura periods)—have generally agreed that much of their focus is on amorous encounters. They have, however, rarely addressed the question of whether these encounters are mutually desirable or, on the contrary, uninvited and therefore aggressive. For fear of anachronism, the topic of sexual violence has not been commonly pursued in the analyses of monogatari. I argue that not only can the phenomenon of sexual violence be clearly defined in the context of the monogatari genre, by drawing on contemporary feminist theories and philosophical debates, but also that it is easily identifiable within the text of these tales, by virtue of the coherent and cohesive patterns used to represent it. In my analysis of seven monogatari—Taketori, Utsuho, Ochikubo, Genji, Yoru no Nezame, Torikaebaya and Ariake no wakare—I follow the development of the textual representations of sexual violence and analyze them in relation to the role of these tales in supporting or subverting existing gender hierarchies. Finally, I examine the connection between representations of sexual violence and the monogatari genre itself. -

RECREATING the PUBLIC and PRIVATE in JAPAN Meghan Sarah Fidler Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2014 PAPER PEOPLE AND DIGITAL MEMORY: RECREATING THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE IN JAPAN Meghan Sarah Fidler Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Fidler, Meghan Sarah, "PAPER PEOPLE AND DIGITAL MEMORY: RECREATING THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE IN JAPAN" (2014). Dissertations. Paper 950. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER PEOPLE AND DIGITAL MEMORY: RECREATING THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE IN JAPAN by Meghan Sarah Fidler B.A. Southern Illinois University, 2004 M.A. Southern Illinois University, 2007 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale December 2014 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAPER PEOPLE AND DIGITAL MEMORY: RECREATING THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE IN JAPAN By Meghan Sarah Fidler A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of PhD. in the field of Anthropology Approved by: David E. Sutton, Chair Andrew Hofling Anthony K. Webster David Slater Roberto Barrios Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale September 12, 2014 AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF MEGHAN SARAH FIDLER, for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in ANTHROPOLOGY, presented on September 12, 2014 at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: PAPER PEOPLE AND DIGITAL MEMORY: RECREATING THE PUBLIC AND PRIVATE IN JAPAN MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. -

Matsuo ■ Basho

; : TWAYNE'S WORLD AUTHORS SERIES A SURVEY OF THE WORLD'S LITERATURE ! MATSUO ■ BASHO MAKOTO UEDA JAPAN MATSUO BASHO by MAKOTO UEDA The particular value of this study of Matsuo Basho is obvious: this is the first book in English that gives a comprehen sive view of the famed Japanese poet’s works. Since the Japanese haiku was en thusiastically received by the Imagists early in this century, Basho has gained a world-wide recognition as the foremost writer in that miniature verse form; he is now regarded as a poet of the highest cali ber in world literature. Yet there has been no extensive study of Basho in Eng lish, and consequently he has remained a rather remote, mystical figure in the minds of those who do not read Japanese. This book examines Basho not only as a haiku poet but as a critic, essayist and linked-verse writer; it brings to light the whole range of his literary achievements that have been unknown to most readers in the West. * . 0S2 VS m £ ■ ■y. I.. Is:< i , • ...' V*-, His. -.« ■ •. '■■ m- m mmm t f ■ ■ m m m^i |«|mm mmimM plf^Masstfa m*5 si v- mmm J 1 V ^ K-rZi—- TWAYNE’S WORLD AUTHORS SERIES A Survey of the World's Literature Sylvia E. Bowman, Indiana University GENERAL EDITOR JAPAN Roy B. Teele, The University of Texas EDITOR Matsuo Basho (TWAS 102) TWAYNES WORLD AUTHORS SERIES (TWAS) The purpose of TWAS is to survey the major writers — novelists, dramatists, historians, poets, philosophers, and critics—of the nations of the world. -

Travel Is Home Travel and Landscape in Japanese Literature, Art, and Culture

TRAVEL IS HOME TRAVEL AND LANDSCAPE IN JAPANESE LITERATURE, ART, AND CULTURE Paper Abstracts (in alphabetical order): Sonia Favi, John Rylands Research Institute, The University of Manchester Meisho as Spaces of Contested Social Meaning in Edo Japan: The Case of Mount Fuji My paper discusses the role of maps and commercial prints of meisho as ways to re-discuss the meaning of space, and consequently the social and geographical boundaries imposed by the bakuhan state, in Edo Japan. The contested nature of the centralized social system imposed by the Tokugawa bakufu has been the object of a lively debate in studies on Edo Japan (see Tsutsui, 2007). Travel studies may provide fresh insight into this debate, as travel, a common practice within the bakuhan state (Ashiba, 1994; Vaporis, 1994; Vaporis, 1995; Nenzi, 2008; Funck and Cooper, 2013), was and is strictly entwined with social mobility, in a way that alters and marks social and cultural landscapes (Lean and Staiff, 2016). This process of transformation is reflected in travel literature, including disposable culture such as commercial prints and maps: these materials, in fact, “mirror and reproduce a whole range of taken-for-granted notions [about] understandings of history and culture.” (Hogan, 2008, 169) Representations of meisho are particularly interesting when analyzed in this perspective, as they were invested with (different, contested) meanings by a wide range of social actors: they were part of a new “official” landscape – a controlled landscape strategically devoid of travelers – in Tokugawa sponsored maps; they were invested with both religious and commercial meaning in religious maps; they were projected into a lyrical past in representations meant for a cultured audience; they were used as a way to reclaim spaces that for practical or normative reasons could not materially be experienced in other popular, commercial representations – that became “virtual” ways to defy boundaries and social conventions. -

Book 2 Names Omitted.Indd

The 3rd EAJS Conference in Japan 第三回EAJS日本会議 BOOK OF ABstRacts The University of Tsukuba Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences 14 - 15 September 2019 Supported by the Japan Foundation Contents Section A - Anthropology & Sociology / Urban & Environmental Studies ........................................................3 Section B - Visual & Performing Arts, Film & Media Studies ................................................................................36 Section C - History ................................................................................65 Section D - Language, Linguistics, Translating & Teaching ......................................................................................100 Section E - Literature ...........................................................................131 Section F - Politics, International Relations & Economics ......................171 Section G - Religion & Philosophy .......................................................181 Section H - Other Disciplines / Interdisciplinary ....................................197 Anthropology & Sociology / Urban & Environmental Studies Section A - Anthropology & Sociology / Urban & Environmental Studies Section Convenors: Jun‘ichi Akashi (University of Tsukuba), Alyne Delany (Tohuku University) & Hidehiro Yamamoto (University of Tsukuba) A-1-1 Zuzanna Baraniak-Hirata (Ochanomizu University) CONSUMING THE “WORLD OF DREAMS”: NARRATIVES OF BELONGING IN TAKARAZUKA FAN CULTURE Recent fan culture studies have often focused on formation of fan communi- -

Representations of Travel in Medieval Japan by Kendra D. Strand A

Aesthetics of Space: Representations of Travel in Medieval Japan by Kendra D. Strand A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in The University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Emerita Professor Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen, Chair Associate Professor Kevin Gray Carr Professor Ken K. Ito, University of Hawai‘i Manoa Associate Professor Jonathan E. Zwicker © Kendra D. Strand 2015 Dedication To Gregory, whose adventurous spirit has made this work possible, and to Emma, whose good humor has made it a joy. ii Acknowledgements Kind regards are due to a great many people I have encountered throughout my graduate career, but to my advisors in particular. Esperanza Ramirez-Christensen has offered her wisdom and support unfalteringly over the years. Under her guidance, I have begun to learn the complexities in the spare words of medieval Japanese poetry, and more importantly to appreciate the rich silences in the spaces between those words. I only hope that I can some day attain the subtlety and dexterity with which she is able to do so. Ken Ito and Jonathan Zwicker have encouraged me to think about Japanese literature and to develop my voice in ways that would never have been possible otherwise, and Kevin Carr has always been incredibly generous with his time and knowledge in discussing visual cultural materials of medieval Japan. I am indebted to them for their patience, their attention, and for initiating me into their respective fields. I am grateful to all of the other professors and mentors with whom I have had the honor of working at the University of Michigan and elsewhere: Markus Nornes, Micah Auerback, Hitomi Tonomura, Leslie Pinkus, William Baxter, David Rolston, Miranda Brown, Laura Grande, Youngju Ryu, Christi Merrill, Celeste Brusati, Martin Powers, Mariko Okada, Keith Vincent, Catherine Ryu, Edith Sarra, Keller Kimbrough, Maggie Childs, and Dennis Washburn. -

He Arashina Iary

!he "arashina #iary h A WOMAN’S LIFE IN ELEVENTH-CENTURY JAPAN READER’S EDITION ! ! SUGAWARA NO TAKASUE NO MUSUME TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY SONJA ARNTZEN AND ITŌ MORIYUKI Columbia University Press New York Columbia University Press Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex cup .columbia .edu Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sugawara no Takasue no Musume, – author. | Arntzen, Sonja, – translator. | Ito, Moriyuki, – translator. Title: *e Sarashina diary : a woman’s life in eleventh-century Japan / Sugawara no Takasue no Musume ; translated, with an introduction, by Sonja Arntzen and Ito Moriyuki. Other titles: Sarashina nikki. English Description: Reader’s edition. | New York : Columbia University Press, [] | Series: Translations from the Asian classics | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN (print) | LCCN (ebook) | ISBN (electronic) | ISBN (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN (pbk. : acid-free paper) Subjects: LCSH: Sugawara no Takasue no Musume, —Diaries. | Authors, Japanese—Heian period, –—Diaries. | Women— Japan—History—To . Classification: LCC PL.S (ebook) | LCC PL.S Z (print) | DDC ./ [B] —dc LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America Cover design: Lisa Hamm Cover image: A bi-fold screen by calligrapher Shikō Kataoka (–). CONTENTS Preface to the Reader’s Edition vii Introduction xi Sarashin$ Diar% Appendix . Family and Social Connections Appendix . Maps Appendix . List of Place Names Mentioned in the Sarashina Diary Notes Bibliography Index PREFACE TO THE READER’S EDITION he Sarashina Diary: A Woman’s Life in Eleventh-Century Japan was published in . -

Heian Court Poetry-1.Indd

STRUMENTI PER LA DIDATTICA E LA RICERCA – 159 – FLORIENTALIA Asian Studies Series – University of Florence Scientific Committee Valentina Pedone, Coordinator, University of Florence Sagiyama Ikuko, Coordinator, University of Florence Alessandra Brezzi, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Marco Del Bene, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Paolo De Troia, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Fujiwara Katsumi, University of Tokyo Guo Xi, Jinan University Hyodo Hiromi, Gakushuin University Tokyo Federico Masini, University of Rome “La Sapienza” Nagashima Hiroaki, University of Tokyo Chiara Romagnoli, Roma Tre University Bonaventura Ruperti, University of Venice “Ca’ Foscari” Luca Stirpe, University of Chieti-Pescara “Gabriele d’Annunzio” Tada Kazuomi, University of Tokyo Massimiliano Tomasi, Western Washington University Xu Daming, University of Macau Yan Xiaopeng, Wenzhou University Zhang Xiong, Peking University Zhou Yongming, University of Wisconsin-Madison Published Titles Valentina Pedone, A Journey to the West. Observations on the Chinese Migration to Italy Edoardo Gerlini, The Heian Court Poetry as World Literature. From the Point of View of Early Italian Poetry Ikuko Sagiyama, Valentina Pedone (edited by), Perspectives on East Asia Edoardo Gerlini The Heian Court Poetry as World Literature From the Point of View of Early Italian Poetry Firenze University Press 2014 The Heian Court Poetry as World Literature : From the Point of View of Early Italian Poetry / Edoardo Gerlini. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2014. (Strumenti per la didattica e la ricerca ; 159) http://digital.casalini.it/9788866556046 ISBN 978-88-6655-600-8 (print) ISBN 978-88-6655-604-6 (online PDF) Progetto grafico di Alberto Pizarro Fernández, Pagina Maestra snc Peer Review Process All publications are submitted to an external refereeing process under the responsibility of the FUP Editorial Board and the Scientific Committees of the individual series. -

Four Japanese Travel Diaries of the Middle Ages

FOUR JAPANESE TRAVEL DIARIES OF THE MIDDLE AGES Translated from the Japanese with NOTES by Herbert PJutschow and Hideichi Fukuda and INTRODUCfION by Herbert Plutschow East Asia Program Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853 The CornellEast Asia Series is published by the Cornell University East Asia Program (distinctfromCornell University Press). We publish affordablypriced books on a variety of scholarly topics relating to East Asia as a service to the academic community and the general public. Standing orders, which provide for automatic notification and invoicing of each title in the series upon publication, are accepted. Ifafter review byinternal and externalreaders a manuscript isaccepted for publication, it ispublished on the basisof camera-ready copy provided by the volume author. Each author is thus responsible for any necessary copy-editingand for manuscript fo1·111atting.Address submission inquiries to CEAS Editorial Board, East Asia Program, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853-7601. Number 25 in the Cornell East Asia Series Online edition copyright© 2007, print edition copyright© 1981 Herbert Plutschow & Hideichi Fukuda. All rights reserved ISSN 1050-2955 (for1nerly 8756-5293) ISBN-13 978-0-939657-25-4 / ISBN-to 0-939657-25-2 CAU'I'ION: Except for brief quotations in a review, no part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any for1n without per1nissionin writing from theauthor. Please address inquiries to Herbert Plutschow & Hideichi Fukuda in care of the EastAsia Program, CornellUniversity, 140 Uris Hall, Ithaca, -

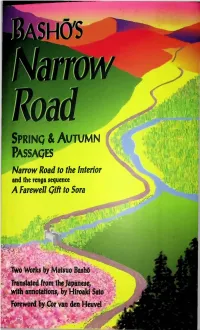

Spring &Autumn

Spring & Autumn Passages Narrow Road to the Interior and the renga sequence A Farewell Qift to Sora iV-y, . p^: Two Works by Matsuo BasM Translated from the Japanese, with annotations, by Hiroaki Sato Foreword by Cor van den Heuvel '-f BASHO'S NARROW ROAD i j i ; ! ! : : ! I THE ROCK SPRING COLLECTION OF JAPANESE LITERATURE ; BaSHO'S Narrow Road SPRINQ & AUTUMN PASSAQES Narrow Road to the Interior AND THE RENGA SEQUENCE A Farewell Gift to Sora TWO WORKS BY MATSUO BASHO TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE, WITH ANNOTATIONS, BY Hiroaki Sato FOREWORD BY Cor van den Heuvel STONE BRIDGE PRESS • Berkeley,, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O, Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stoncbridgc.com Cover design by Linda Thurston. Text design by Peter Goodman. Text copyright © 1996 by Hiroaki Sato. Signature of the author on front part-title page: “Basho.” Illustrations by Yosa Buson reproduced by permission of Itsuo Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG1NG-1N-PUBL1 CATION DATA Matsuo, BashO, 1644-1694. [Oku no hosomichi. English] Basho’s Narrow road: spring and autumn passages: two works / by Matsuo Basho: translated from the Japanese, with annotations by Hiroaki Sato. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Narrow road to the interior and the renga sequence—A farewell gift to Sora. ISBN 1-880656-20-5 (pbk.) 1- Matsuo, Basho, 1644-1694—Journeys—Japan.