Our Pasts – III

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactions of Emperor Bahādur Shāh Zafar and Laureate Mirzā Ghālib to the Celestial Events During 1857-1858

Indian Journal of History of Science, 53.3 (2018) 325-340 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2018/v53i3/49464 Historical Note Reactions of Emperor Bahādur Shāh Zafar and Laureate Mirzā Ghālib to the Celestial Events during 1857-1858 R C Kapoor* (Received 13 December 2017; revised 05 June 2018) Abstract The revolt against the British broke out at Meerut on 10th May 1857 that soon turned into a Great Uprising and shook the foundations of the colonial power in India. A conjunction of Mars and Saturn took place in July 1857. A solar eclipse occurred on 18th September 1857, two days before the capture of Delhi by the British. There followed a lunar eclipse, on 28th February 1858. Then a comet brightened up in the evening skies only days before the British Crown was about to take India in its fold on 1st November 1858. How Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar (1775-1862), central to the upheaval, and the laureate Mirzā Ghālib (1797-1859), a remote observer, reacted in such a scenario is central to our theme. Z. afar was a superstitious man and had a spiritual incline. What is unique is that he had never mixed up the outcome of the war with the celestial events and left it to Almighty. That he was unaware of these events is difficult to believe. Ghālib was a skeptic and came to believe the celestial events as signals of divine wrath. In the process we discover an unexplored side of Mirzā Ghālib and his grasp of astronomy. Key words: Annular solar eclipse of 1857, Bahadur Shah Zafar, Donati’s Comet, India’s Great Uprising of 1857, Mirzā Ghālib, Mughal India. -

Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar

H-Announce Performing Law, Staging History: The (Re)Trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar Announcement published by Kanika Sharma on Monday, December 9, 2019 Type: Call for Papers Date: January 6, 2020 Location: India Subject Fields: Art, Art History & Visual Studies, Colonial and Post-Colonial History / Studies, South Asian History / Studies, Law and Legal History, Theatre & Performance History / Studies This one-day interdisciplinary roundtable aims to bring together academics and practitioners from various fields including law, history, military studies, theatre, visual culture, politics and literature to analyse the Uprising of 1857 and the subsequent trial of the last Mughal Emperor of India at the Red Fort in Delhi. At the roundtable we will seek to interrogate how legal and historical knowledge around the Uprising and trial was/is produced, established, legitimised and potentially subverted, with a special emphasis on the role played by images and theatricality in these processes. Papers may speak to (though they need not be limited to) the following themes in relation to the Uprising of 1857 and the subsequent trial of Bahadur Shah Zafar: Law and colonialism; International law and victor’s justice; Performance and the political trial; The use of images and architecture in show trials; Military history in India; Religion, race and nationalism; and Imaginations of the Uprising in popular culture. This roundtable is the first step in developing an interactive theatre performance around Zafar’s trial. The performance will be accompanied by a visual installation focusing on the Uprising based on rare images from The Alkazi Collection of Photography at The Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi. -

Phoolwalon Ki Sair.Indd 1 27/07/12 1:21 PM 1

CORONATION To the south of the western gateway is the tomb of Qutb Sahib. was meant for the grave of Bahadur Shah Zafar, who was however PARK It is a simple structure enclosed by wooden railings. The marble exiled after the Mutiny and died in Burma. balustrade surrounding the tomb was added in 1882. The rear wall To the north-east of the palace enclosure lies an exquisite mosque, Phoolwalon was added by Fariduddin Ganj-e-Shakar as a place of prayer. The the Moti Masjid, built in white marble by Bahadur Shah I in the early western wall is decorated with coloured fl oral tiles added by the eighteenth century as a private mosque for the royal family and can be Delhi Metro Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb. approached from the palace dalan as well as from the Dargah Complex. Route 6 ki Sair The screens and the corner gateways in the Dargah Complex were Civil Ho Ho Bus Route built by the Mughal emperor Farrukhsiyar. The mosque of Qutb Lines Heritage Route Sahib, built in mid-sixteenth century by Islam Shah Suri, was later QUTBUDDIN BAKHTIYAR KAKI DARGAH AND ZAFAR added on to by Farrukhsiyar. MAHAL COMPLEX The Dargah of Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki continues to be a sacred place for the pilgrims of different religions. Every week on Thursday 5 SHAHJAHANABAD Red Fort and Friday qawwali is also performed in the dargah. 5. ZAFAR MAHAL COMPLEX 6 Kotla 9 Connaught Firoz Shah Adjacent to the western gate of the Dargah of Place Jantar Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, this complex Mantar 2 7 8 NEW DELHI has various structures built in 3 Route 5 1 Rashtrapati the eighteenth and nineteenth 4 Bhavan Purana century. -

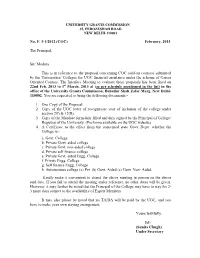

No. F. 1-1/2012 (COC) February, 2013 the Principal

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION 35, FEROZESHAH ROAD NEW DELHI-110001 No. F. 1-1/2012 (COC) February, 2013 The Principal, Sir/ Madam, This is in reference to the proposal concerning COC (add-on courses) submitted by the Universities/ Colleges for UGC financial assistance under the scheme of Career Oriented Courses. The Interface Meeting to evaluate these proposals has been fixed on 22nd Feb, 2013 to 1st March, 2013 at (as per schedule mentioned in the list) in the office of the University Grants Commission, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi- 110002. You are requested to bring the following documents:- 1. One Copy of the Proposal. 2. Copy of the UGC letter of recognition/ year of inclusion of the college under section 2(f) & 12(B). 3. Copy of the Mandate form duly filled and duly signed by the Principal of College/ Registrar of the University. (Proforma available on the UGC website) 4. A Certificate to the effect from the concerned state Govt. Deptt. whether the College is:- a. Govt. College b. Private Govt. aided college c. Private Govt. non-aided college d. Private self finance college e. Private Govt. aided Engg. College f. Private Engg. College g. Self finance Engg. College h. Autonomous college (a) Pvt. (b) Govt. Aided (c) Govt. Non- Aided. Kindly make it convenient to attend the above meeting in person on the above said date. If you fail to attend the meeting under reference, no other dates will be given. However, it may further be noted that the Principal of the College may have to stay for 2- 3 more days subject to the availability of Expert Members. -

Revolt of 1857 : the First War of Independence

International Journal of Engineering, Management, Humanities and Social Sciences Paradigms (IJEMHS) (Volume 20, Issue 01) Publishing Month: April 2016 An Indexed and Referred Journal with Impact Factor: 2.75 ISSN: 2347-601X www.ijemhs.com Revolt of 1857: The First War of Independence? Dr. Parduman Singh Assistant Professor of History Govt. College for Women, Rohtak, Hr (India) Publishing Date: April 22, 2016 Abstract to induction of Sikhs into the Bengal regiment The dictionary meaning of Uprising is “an act of that created a sense of fear among the soldiers resistance or rebellion or a revolt." Most scholars as a position in the army had become a status have used Mutiny and insurrection interchangeably. symbol for the soldiers which they did not Whether the revolt of 1857 was just another revolt want to lose at any cost.1 “Cantonment after in the long series of revolts against British authority cantonment rebelled. When the soldiers or was it rightly called by some as a war of independence? Before we discuss that let us first refused to acknowledge British authority, the examine the causes that led to this revolt. Reasons way was left open for disaffected princes and for the mutiny are still debatable in academic circles aristocrats, and for village and town people and politico-history discussions. However, it was with grievances, to revolt alongside the not the first revolt against the established authority soldiers.”2Apparently, religion seems to be of the British, yet the impact it left on the masses playing the pivot role in flaring up the revolt. makes it a topic of great deliberation. -

Later Mughal Emperors (1707-1857 A.D.)

Page 1 of 6 Later Mughal Emperors (1707-1857 A.D.) The Mughal Empire was vast and extensive in the beginning of the eighteenth century. But by the close of the century it had shrunk to a few kilometres around Delhi. After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, a war of succession began amongst his three surviving sons, Muazzam – the governor of Kabul, Azam-the governor of Gujarat, and Kam Baksh-the governor of Deccan. Azam turned to Ahmednagar and proclaimed himself emperor. Kam Baksh too declared himself the sovereign ruler and conquered important places as Gulbarga and Hyderabad. Muazzam defeated both Azam at Jajau in 1707 and Kam Baksh near Hyderabad in 1708. Muazzam emerged victorious and ascended the Mughal throne with the title of Bahadur Shah I. He was also known as Shah Alam I. Muazzam 'Bahadur Shah I' (1707-1712 A.D.) Jahandar Shah (1712 – 1713 A.D.) Bahadur Shah I was the third son of Aurangzeb He was ascended himself on the throne after with Muslim Rajput wife, Nawab Bai. killing his three brothers with the help of Zulfikar Bahadur Shah's full name was 'Abul-nasr Sayyid Khan who was the leader of Irani Party in Mughals Qutb-ud-din Muhammad Shah Alam Bahadur Shah Court. Badshah' He was puppet of Zulfikar Khan who acts as the He was popularly known as Shah Alam I and defacto ruler which led the foundation of the called Shahi-i- Bekhabar by Khafi Khan due to his concept of king makers. He was also under the appeasement parties by grants of title and influence of his mistress Lal Kunwar which rewards. -

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ( April, 2019 - March, 2020 ) (In Compliance with Section 18 of the UGC Act,1956 (No. 13 of 1956) UGC have the honour to present to the Central Government the Annual Report of the University Grants Commission for the year 2019-20 to be laid before the Parliament) University Grants Commission Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi-110002 (India) Website : www.ugc.ac.in University Grants Commission Composition 1. The Commission shall consist of- (i) A Chairman (ii) A Vice- Chairman, and (iii) ten other members, to be appointed by the Central Government. 2. The Chairman shall be chosen from among persons who are not officers of the Central Government or of any State Government. 3. Of the other members referred to in clauses (iii) of sub-section (1): (a) two shall be chosen from among the officers of the Central Government, to represent that Government.; (b) not less than four shall be chosen from among persons who are at the time when they are so chosen, teachers of Universities; and (c) the remainder shall be chosen from among persons:- (i) who have knowledge of, or experience in, agriculture, commerce, forestry or industry; (ii) who are members of the engineering, legal, medical or any other learned profession; or (iii) who are Vice-Chancellors of Universities or who, not being teachers of Universities, are in the opinion of the Central Government, educationists of repute or have obtained high academic distinctions. Provided that not less than one-half of the number chosen under this clause shall be from among persons who are not officers of the Central Government or of any State Government. -

Teaching Guide 8.Pdf

HISTORY GEOGRAPHY Social Studies for Pakistan CIVICS 8 Know Your World Teaching Guide KHADIJA CHAGLA-BAIG A C O M P R E H E N S I V E C O U R S E F O R S E C O N D A R Y CL AS SES 1 History Chapter 1 The Decline of the Mughals 01 Chapter 2 The Marathas and The Sikhs 06 Chapter 3 European Colonization of the Subcontinent 12 Chapter 4 The British East India Company 18 Chapter 5 The British Raj 23 Chapter 6 The Subcontinent after the War of Independence 31 Geography Chapter 7 The Atmosphere 38 Chapter 8 All About Winds 44 Chapter 9 Climatic Zones and the Wildlife 49 Chapter 10 Conservation of Natural Resources 53 Chapter 11 Population 57 Chapter 12 Some Major Urban Centres of the World 62 Chapter 13 Transport and Communication 64 Civics Chapter 14 The Value of Knowledge and Teachers 69 Chapter 15 Dealing with Negative Feelings 72 Chapter 16 Positive Thinking and Values 75 Chapter 17 Human Rights 77 Answer Key 80 1 iii iv 1 HISTORY CHAPTER 1 The Decline of the Mughals Discussion points All civilizations and empires ultimately end or merge into others. The Mughal Empire was no different. There were many reasons that led to its weakening and the final takeover by the British. However, it was not an overnight process. Signs of weakening began by the end of the 17th century. Many states broke away from the empire and became independent. Intrigues and rebellions by previously suppressed groups surged beyond control. -

University Grants Commission Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg New Delhi – 110 002

Annexure -VIII UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI – 110 002. Final Report of the work done on the Major Research Project. 1. Project report No. Final 2. UGC Reference No.F. 42-425/2013 (SR) dated 22/3/2013 3. Period of report: from April 01, 2013 to March 31, 2017. 4. Title of research project: `Study on variation of biochemical indicators of stress due to deposition of urban dust on foliar surface of selected plants in National Capital Region of Delhi’ 5. (a) Name of the Principal Investigator: Prof. Umesh Kulshrestha (b) Deptt.: School of Environmental Sciences (c) University/College where work has progressed Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 6. Effective date of starting of the project: April 01, 2013 7. Grant approved and expenditure incurred during the period of the report: Total amount approved: Rs. 10,61,800/- Total expenditure: Rs. 10,59,788/- Summary of the project: The abundance of atmospheric dust in the atmosphere in the Indian region, significantly affects various surfaces through its freefall deposition including the leaves, water bodies, vegetation, soils etc resulting in alterations in the nature and composition of the surface. Sometimes the impact of dusfall deposition on plants results in changes in their biochemistry and related physiochemical parameters. This study revealed that the accumulation of atmospheric dust on plant leaves The deposition of dust particles on the leaves affects the physio-biochemical properties of the plants. In the present study, impact of chemical components of dust was noticed on the biochemical constituents of a medicinally important tropical plants Arjun (Terminalia arjuna) and Mulberry (Morus alba) at a residential (Jawaharlal Nehru University, JNU) and an industrial site (Sahibabad, SB) in Delhi. -

The Indian Rebellion of 1857

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 The Indian Rebellion of 1857 began as a mutiny of sepoys of the East India Company's army on 10 May 1857, in the cantonment of the town of Meerut, and soon escalated into other mutinies and civilian rebellions largely in the upper Gangetic plain and central India, with the major hostilities confined to present-day Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, northern Madhya Pradesh, and the Delhi region. The rebellion posed a considerable threat to East India Company power in that region, and was contained only with the fall of Gwalior on 20 June 1858. The rebellion is also known as India's First War of Independence, the Great Rebellion, the Indian Rebellion, the Indian Mutiny, the Revolt of 1857, the Rebellion of 1857, the Uprising of 1857, the Sepoy Rebellion and the Sepoy Mutiny. Other regions of Company-controlled India – such as Bengal, the Bombay Presidency, and the Madras Presidency – remained largely calm. In Punjab, the Sikh princes backed the Company by providing soldiers and support. The large princely states of Hyderabad, Mysore, Travancore, and Kashmir, as well as the smaller ones of Rajputana, did not join the rebellion. In some regions, such as Oudh, the rebellion took on the attributes of a patriotic revolt against European presence. Maratha leaders, such as Lakshmibai, the Rani of Jhansi, became folk heroes in the nationalist movement in India half a century later; however, they themselves generated no coherent ideology for a new order. The rebellion led to the dissolution of the East India Company in 1858. It also led the British to reorganize the army, the financial system and the administration in India. -

The Life and Reign of Bahadur Shah Zafar INTRODUCTION

The Life and Reign of Bahadur Shah Zafar Sourced from- https://www.wikipedia.org INTRODUCTION Bahadur Shah Zafar or Bahadur Shah II was born as Mirza Abu Zafar Siraj-ud- din Muhammad on 24th October, 1775 in Shahjahanabad, present day Delhi to Mughal Emperor Akbar Shah II and Lela Banu Begum (Lal Bai, a Hindu Rajput princess). Bahadur Shah II, being the last emperor of India, was also called ‘Badshah’ or ‘Shahanshah-e-Hind’. By the time Bahadur Shah Zafar ascended the throne, the area under Mughal rule was drastically reduced, as were the emperor’s powers, symbolic and otherwise, and thus he was ultimately known only as the ‘King of Delhi’. He was a musician, calligrapher, and poet, with so much more aesthetics with mere knowledge of politics. He received his education in Arabic and Persian. He was born in the royal family and as a prince he was trained in the military arts of horsemanship, shooting with arrow and bows, swordsmanship and with fire-arms. He was also excellent in calligraphy and also use his talent to write Quran by himself which was sent to famous mosques around Delhi as gift. BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR’S FATHER- AKBAR SHAH II Sourced from- https://www.wikipedia.org BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR’S MOTHER- LAL BAI Sourced from- geni.com SHAHJAHANABAD- BIRTHPLACE OF BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR Sourced from- kamit.jp BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR’S CALLIGRAPHY Sourced from – granger.com FAMILY TREE OF BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR Sourced from-timesofindia.indiatimes.com Bahadur Shah Zafar had four queens; Ashraf Mahal, Akhtar Mahal, Zeenat Mahal, and Taj Mahal. -

Ellis New Delhi Recommendatio

Recommendations for a Short Stay NewDeLHI Written by Kirsten Ellis Directed by Hans Hiifer Design Concept by V. Bari Art Direction by Karen Hoisington Photography by Pankaj Shah Editorial Director Michael Stachels 0 Insight Pocket Guide: NeWDeLHI FirstEdilion © 1991 APA Publications (HK) Ltd All Rights Rese1wd Printed in Singapore by Hiifer Press (Ple) Ltd No part of this book may be reproduced. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or means electronic, mechanical. photocopying, recording or otherwise. without prior written permission of Apa Publications. Brief text quotations with use of photographs are exempted for -'>IUSIOHT book review purposes only IBllllJl1 1:·8 extremely proud of this architectural emblem, which was built irom funds donated from Baha'i devotees across the globe, and like to compare it to the Sydney Opera House, and even the Taj Mahal. It is certainly not the Taj Mahal, although it is made from the same Rajasthani Macrana marble, but it is undeniably impressive. Set in well-tended gardens, each of its sculpted marble "petals" are sur rounded by nine pools and walkways, each leading to a different entrance, which apparently denote the many paths leading to God. Inside the prayer hall tapers to 100 feet (301h meters) high, with no supporting columns, creating a feeling of breathtaking spaciousness and serenity. The Baha'i faith began in present-day Iran in 1844 by Baha'u'llah, a Persian nobleman, who proclaimed himself the "Promised One", who had been entrusted with a message from God that the path to religious truth lay in the spiritual and social unification of the world.