The Slave's Cause: a History of Abolition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

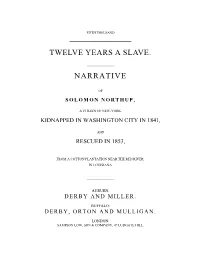

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads. -

The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War By Richard S. Newman, Associate Professor of History Rochester Institute of Technology The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was the world's most famous antislavery group during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, although not as memorable as many later abolitionists (from William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child to Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth), Pennsylvania reformers defined the antislavery movement for an entire generation of activists in the United States, Europe, and even the Caribbean. If you were an enlightened citizen of the Atlantic world following the American Revolution, then you probably knew about the PAS. Benjamin Franklin, a former slaveholder himself, briefly served as the organization's president. French philosophes corresponded with the organization, as did members of John Adams’ presidential Cabinet. British reformers like Granville Sharp reveled in their association with the PAS. It was, Sharp told told the group, an "honor" to be a corresponding member of so distinguished an organization.1 Though no supporter of the formal abolitionist movement, America’s “first man” George Washington certainly knew of the PAS's prowess, having lived for several years in the nation's temporary capital of Philadelphia during the 1790s. So concerned was the inaugural President with abolitionist agitation that Washington even shuttled a group of nine slaves back and forth between the Quaker State and his Mount Vernon home (still, two of his slaves escaped). The PAS was indeed a powerful abolitionist organization. PAS Origins The roots of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society date to 1775, when a group of mostly Quaker men met at a Philadelphia tavern to discuss antislavery measures. -

Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon

PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon Against Slavery Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms.Tasnim BELAIDOUNI Ms.Meriem MENGOUCHI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Wassila MOURO Chairwoman Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI Supervisor Dr. Frid DAOUDI Examiner Academic Year: 2016/2017 Dedications To those who believed in me To those who helped me through hard times To my Mother, my family and my friends I dedicate this work ii Acknowledgements Immense loads of gratitude and thanks are addressed to my teacher and supervisor Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI; this work could have never come to existence without your vivacious guidance, constant encouragement, and priceless advice and patience. My sincerest acknowledgements go to the board of examiners namely; Dr. Wassila MOURO and Dr. Frid DAOUDI My deep gratitude to all my teachers iii Abstract Harriet Ann Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl seemed not to be the only literary work which tackled the issue of woman in slavery. However, this autobiography is the first published slave narrative written in the nineteenth century. In fact, the primary purpose of this research is to dive into Incidents in order to examine the author’s portrayal of a black female slave fighting for her freedom and her rights. On the other hand, Jacobs shows that despite the oppression and the persecution of an enslaved woman, she did not remain silent, but she strived to assert herself. -

Slave Revolts and the Abolition of Slavery: an Overinterpretation João Pedro Marques

Part I Slave Revolts and the Abolition of Slavery: An Overinterpretation João Pedro Marques Translated from the Portuguese by Richard Wall "WHO ABOLISHED SLAVERY?: Slave Revolts and Abolitionism, A Debate with João Pedro Marques" Edited by Seymour Drescher and Pieter C. Emmer. http://berghahnbooks.com/title/DrescherWho "WHO ABOLISHED SLAVERY?: Slave Revolts and Abolitionism, A Debate with João Pedro Marques" Edited by Seymour Drescher and Pieter C. Emmer. http://berghahnbooks.com/title/DrescherWho INTRODUCTION t the beginning of the nineteenth century, Thomas Clarkson por- Atrayed the anti-slavery movement as a river of ideas that had swollen over time until it became an irrepressible torrent. Clarkson had no doubt that it had been the thought and action of all of those who, like Raynal, Benezet, and Wilberforce, had advocated “the cause of the injured Afri- cans” in Europe and in North America, which had ultimately lead to the abolition of the British slave trade, one of the first steps toward abolition of slavery itself.1 In our times, there are several views on what led to abolition and they all differ substantially from the river of ideas imagined by Clarkson. Iron- ically, for one of those views, it is as if Clarkson’s river had reversed its course and started to flow from its mouth to its source. Anyone who, for example, opens the UNESCO web page (the Slave Route project) will have access to an eloquent example of that approach, so radically opposed to Clarkson’s. In effect, one may read there that, “the first fighters for the abolition -

N the Changing Shape of Pro-Slavery Arguments in the Netherlands (1789- 1814)

3 n the changing shape of pro-slavery arguments in the Netherlands (1789- 1814) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320161402 Pepjin Brandon Department of History, VU Amsterdam International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, Netherlands [email protected] Abstract: One of the puzzling questions about the formal Dutch abolition of the slave- trade in 1814 is why a state that was so committed to maintaining slavery in its Empire did not put up any open resistance to the enforced closing of the trade that fed it. The explanations that historians have given so far for this paradox focus mainly on circumstances within the Netherlands, highlighting the pre-1800 decline of the role of Dutch traders in the African slave-trade, the absence of a popular abolitionist movement, and the all-overriding focus within elite-debates on the question of economic decline. This article argues that the (often partial) advanced made by abolitionism internationally did have a pronounced influence on the course of Dutch debates. This can be seen not only from the pronouncements by a small minority that advocated abolition, but also in the arguments produced by the proponents of a continuation of slavery. Careful examination of the three key debates about the question that took place in 1789-1791, 1797 and around 1818 can show how among dominant circles within the Dutch state a new ideology gradually took hold that combined verbal concessions to abolitionist arguments and a grinding acknowledgement of the inevitability of slave-trade abolition with a long-term perspective for prolonging slave-based colonial production in the West-Indies. -

ABOLITIONISTS and the CONSTITUTION Library of Congress/Theodore R

ABOLITIONISTS AND THE CONSTITUTION Library of Congress/Theodore R. Davis R. Congress/Theodore of Library The Constitution allowed Congress to ban the importation of slaves in 1808, but slave auctions, like the one pictured here, continued in southern states in the 19th century. Two great abolitionists, William Lloyd Garrison and deep-seated moral sentiments that attracted many Frederick Douglass, once allies, split over the Constitu- followers (“Garrisonians”), but also alienated many tion. Garrison believed it was a pro-slavery document others, including Douglass. from its inception. Douglass strongly disagreed. Garrison and Northern Secession Today, many Americans disagree about how to in- Motivated by strong, personal Christian convic- terpret the Constitution. This is especially true with our tions, Garrison was an uncompromising speaker and most controversial social issues. For example, Ameri- writer on the abolition of slavery. In 1831, Garrison cans disagree over what a “well-regulated militia” launched his own newspaper, The Liberator, in means in the Second Amendment, or whether the gov- Boston, to preach the immediate end of slavery to a ernment must always have “probable cause” under the national audience. In his opening editorial, he in- Fourth Amendment to investigate terrorism suspects. formed his readers of his then radical intent: “I will These kinds of disagreements about interpretation are not retreat a single inch, and I will be heard!” not new. In fact, they have flared up since the Consti- Garrison also co-founded the American Anti- tutional Convention in 1787. One major debate over the Slavery Society (AAS) in Boston, which soon had Constitution’s meaning caused a rift in the abolitionist over 200,000 members in several Northern cities. -

Tubman Home for the Aged/Harriet Tubman Residence/Thompson

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 TUBMAN HOME FOR THE AGED, HARRIET TUBMAN RESIDENCE AND THOMPSON A.M.E. ZION CHURCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: TUBMAN HOME FOR THE AGED, HARRIET TUBMAN RESIDENCE, THOMPSON A.M.E. ZION CHUCH Other Name/Site Number: Harriet Tubman District Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, NY 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 180 South Street Not for publication: 182 South Street 33 Parker Street City/Town: Auburn Vicinity: State: NY County: Cayuga Code: Oil Zip Code: 13201 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local: __ District: ___ Public-State: __ Site: ___ Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 3 4 buildings _ sites __ structures __ objects 4 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 4 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: (National Register)Historic Properties Relating to Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 TUBMAN HOME FOR THE AGED, HARRIET TUBMAN RESIDENCE AND THOMPSON A.M.E. ZION CHURCH Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

A Guide to the Underground Railroad in New Jersey

N EW J ERSEY’ S U NDERGROUND R AILROAD H ERITAGE “Steal Away, Steal Away...” A Guide to the Underground Railroad in New Jersey N EW J ERSEY H ISTORICAL C OMMISSION Introduction Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus Steal away, steal away home, I ain’t got long to stay here — Negro spiritual ome of those daring and artful runaway slaves who entered New Jersey by way of the Underground Railroad (UGRR) no doubt sang the words of old Negro spirituals like "Steal Away" before embarking on their perilous journey north. The lyrics of these S precious black folk songs indeed often had double meanings, serving as code songs that conveyed plans to escape the yoke of bondage. The phrase "steal away" thus meant absconding; "Jesus" and "home" symbolized the yearned for freedom in the North; and the words "I ain’t got long to stay here" meant that flight northward was imminent. Running away as a form of protest by slaves against their bondage is as old as African enslavement itself on American soil. The first European settlement on land that would ultimately become part of the United States of America, a Spanish colony established in 1526 in the area of present-day were connected to the Underground Railroad, that secret South Carolina, witnessed the flight of its slaves; it is said they network of persons and places—sometimes well organized and fled to neighboring Indians. The presence of African slaves in other times loosely structured—that helped southern runaway the British colonies of North America, whose history begins slaves reach safety in the northern states and Canada. -

Debates Over Slavery and Abolition: an Interpretative and Historiographical Essay

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. Debates Over Slavery and Abolition: An Interpretative and Historiographical Essay Orville Vernon Burton Clemson University Various source media, Slavery and Anti-Slavery: A Transnational Archive EMPOWER™ RESEARCH Slavery is an ugly word, and the vast majority of modern enslaved in the seventeenth century, frequently being readers would immediately identify it as an ugly shipped to the West Indies. Europeans introduced a concept. Any effort to reintroduce the institution in the complex slave trade to their new Indian neighbors, United States would no doubt be vigorously resisted by often pitting tribe against tribe to obtain captives to sell all but a marginal few; most citizens, in fact, would into slavery. By the eighteenth century, however, wonder how such a proposal could even be seriously slavery as practiced by Europeans almost exclusively debated, or how support for it could be buttressed by victimized Africans by means of the triangular slave anything other than ignorance or the most unmitigated trade. form of selfishness. Slavery in colonial and early America existed in both the People, however, tend to have short memories (which is North and the South. For example, slavery was why they need historians). Slavery had been a common in New York. Even by the Civil War, there were commonly accepted fact of life since before written still a few remaining slaves in New Jersey, which had records began and has lingered in some parts of the ended slavery through gradual emancipation but like world until the present time. In the past, individuals other northern states had become a free state. -

The African-American Community's Response to Uncle Tom Spencer York Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2016 A Family Dispute: The African-American Community's Response to Uncle Tom Spencer York Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation York, Spencer, "A Family Dispute: The African-American Community's Response to Uncle Tom" (2016). All Theses. 2426. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FAMILY DISPUTE: THE AFRICAN-AMERICAN COMMUNITY’S RESPONSE TO UNCLE TOM A Thesis Presented To The Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts History by Spencer York August 2016 Accepted by: Dr. Paul Anderson, Committee Chair Dr. Abel Bartley Dr. Orville Vernon Burton Abstract This thesis is an attempt to understand the complex relationship between the African-American community and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It argues that a large reason for the negative connotation of “uncle Tom” within the African-American community was caused by conflicts between intellectual patterns and traditions of the community and Stowe’s vision in her novel. This thesis looks at the key texts in the intellectual history of the African-American community, including the literary responses by African Americans to the novel. This thesis seeks to fill gaps in the history of the African-American community by looking at how members of the community exercised their agency to achieve the betterment of the community, even in the face of white opposition.