Harriet Jacobs and the Transatlantic Movement 10/10/01 1 of 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK WOMEN ARE LEADERS Long Form

BLACK WOMEN ARE LEADERS IN THE MOVEMENT TO END SEXUAL & DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Ida B. Wells The Combahee River Collective Wells, a suffragist and temperance activist, famously and fearlessly This Boston-based collective spoke against lynchings, and also of black feminist lesbians worked to end sexual violence wrote the seminal essay The against black women. Radically, Combahee River Collective Wells identified scapegoating of Statement, centering black black men as rapists as a projection feminist issues and identifying of white men's own history of sexual white feminism as an entity violence, often enacted against black that often excludes or women. sidelines black women. They campaigned against sexual assault in their communities and raised awareness of the racialized sexual Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw violence that black women face. A legal scholar, writer, and activist, Crenshaw famously coined the term Loretta Ross "intersectionality," forever impacting An academic, activist, and writer, the way we think about social identity. Ros s has written extensively on Crenshaw's work draws attention to the topic of reproductive justice the fact that black women exist at the and is a pioneer of reproductive intersection of multiple oppressions justice theory. Her work has and experience the dual violence of brought attention to the ways both racism and misogyny. reproductive coercion, racism, and sexual violence intersect. Harriet Jacobs Tarana Burke Jacobs was born into An activist and public speaker, Burke slavery and sex ually founded the wildly successful assaulted by her owner, #MeToo movement. Specifically and eventually escaped created to highlight violence by hiding undetected in experienced by marginalized an attic for seven years. -

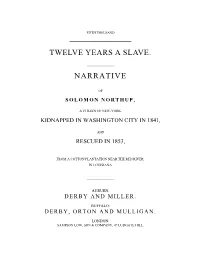

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads. -

The Slave's Cause: a History of Abolition

Civil War Book Review Summer 2016 Article 5 The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Corey M. Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Brooks, Corey M. (2016) "The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 18 : Iss. 3 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.18.3.06 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol18/iss3/5 Brooks: The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Review Brooks, Corey M. Summer 2016 Sinha, Manisha The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition. Yale University Press, $37.50 ISBN 9780300181371 The New Essential History of American Abolitionism Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause is ambitious in size, scope, and argument. Covering the entirety of American abolitionist history from the colonial era through the Civil War, Sinha, Professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, presents copious original research and thoughtfully and thoroughly mines the substantial body of recent abolitionist scholarship. In the process, Sinha makes a series of potent, carefully intertwined arguments that stress the radical and interracial dimensions and long-term continuities of the American abolitionist project. The Slave’s Cause portrays American abolitionists as radical defenders of democracy against countervailing pressures imposed both by racism and by the underside of capitalist political economy. Sinha goes out of her way to repudiate outmoded views of abolitionists as tactically unsophisticated utopians, overly sentimental romantics, or bourgeois apologists subconsciously rationalizing the emergent capitalism of Anglo-American “free labor" society. In positioning her work against these interpretations, Sinha may somewhat exaggerate the staying power of that older historiography, as most (though surely not all) current scholars in the field would likely concur wholeheartedly with Sinha’s valorization of abolitionists as freedom fighters who achieved great change against great odds. -

The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War By Richard S. Newman, Associate Professor of History Rochester Institute of Technology The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was the world's most famous antislavery group during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, although not as memorable as many later abolitionists (from William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child to Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth), Pennsylvania reformers defined the antislavery movement for an entire generation of activists in the United States, Europe, and even the Caribbean. If you were an enlightened citizen of the Atlantic world following the American Revolution, then you probably knew about the PAS. Benjamin Franklin, a former slaveholder himself, briefly served as the organization's president. French philosophes corresponded with the organization, as did members of John Adams’ presidential Cabinet. British reformers like Granville Sharp reveled in their association with the PAS. It was, Sharp told told the group, an "honor" to be a corresponding member of so distinguished an organization.1 Though no supporter of the formal abolitionist movement, America’s “first man” George Washington certainly knew of the PAS's prowess, having lived for several years in the nation's temporary capital of Philadelphia during the 1790s. So concerned was the inaugural President with abolitionist agitation that Washington even shuttled a group of nine slaves back and forth between the Quaker State and his Mount Vernon home (still, two of his slaves escaped). The PAS was indeed a powerful abolitionist organization. PAS Origins The roots of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society date to 1775, when a group of mostly Quaker men met at a Philadelphia tavern to discuss antislavery measures. -

African American Reaction to Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation

“God Is Settleing the Account”: African American Reaction to Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation HE WHITE MAN SEATED ACROSS THE ROOM was offering them a new life in a land of opportunity. Against the backdrop of TWashington’s sweaty August, in 1862, he told his five black guests from the District of Columbia about a temperate, welcoming place, with fine harbors, exotic flora and fauna, and vast reserves of minerals. “There is evidence of very rich coal mines,” he offered. Surely they—ministers, teachers, and a congressional messenger—could understand that whites (notwithstanding his own feelings) would never treat them as equals on American soil. “Your race are suffering, in my judgment, the greatest wrong inflicted on any people,” he told them. But he seemed more con- cerned with injuries to his own race: “See our present condition—the country engaged in war!—our white men cutting one another’s throats. But for your race among us, there could not be war.” He offered to finance their passage to a new home in a mountainous quarter of the Isthmus of Panama known as Chiriquí. The government had in hand a glowing report on everything from Chiriquí’s climate and coal to its value as a forward post of US influence in Central America. This article is adapted and expanded from our book Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America (Philadelphia, 2010). Other major sources include Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York, 2010); Kate Masur, “The African American Delegation to Abraham Lincoln: A Reappraisal,” Civil War History 56 (2010): 117–44; and numerous documents reviewed in C. -

Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon

PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon Against Slavery Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms.Tasnim BELAIDOUNI Ms.Meriem MENGOUCHI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Wassila MOURO Chairwoman Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI Supervisor Dr. Frid DAOUDI Examiner Academic Year: 2016/2017 Dedications To those who believed in me To those who helped me through hard times To my Mother, my family and my friends I dedicate this work ii Acknowledgements Immense loads of gratitude and thanks are addressed to my teacher and supervisor Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI; this work could have never come to existence without your vivacious guidance, constant encouragement, and priceless advice and patience. My sincerest acknowledgements go to the board of examiners namely; Dr. Wassila MOURO and Dr. Frid DAOUDI My deep gratitude to all my teachers iii Abstract Harriet Ann Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl seemed not to be the only literary work which tackled the issue of woman in slavery. However, this autobiography is the first published slave narrative written in the nineteenth century. In fact, the primary purpose of this research is to dive into Incidents in order to examine the author’s portrayal of a black female slave fighting for her freedom and her rights. On the other hand, Jacobs shows that despite the oppression and the persecution of an enslaved woman, she did not remain silent, but she strived to assert herself. -

Slave Revolts and the Abolition of Slavery: an Overinterpretation João Pedro Marques

Part I Slave Revolts and the Abolition of Slavery: An Overinterpretation João Pedro Marques Translated from the Portuguese by Richard Wall "WHO ABOLISHED SLAVERY?: Slave Revolts and Abolitionism, A Debate with João Pedro Marques" Edited by Seymour Drescher and Pieter C. Emmer. http://berghahnbooks.com/title/DrescherWho "WHO ABOLISHED SLAVERY?: Slave Revolts and Abolitionism, A Debate with João Pedro Marques" Edited by Seymour Drescher and Pieter C. Emmer. http://berghahnbooks.com/title/DrescherWho INTRODUCTION t the beginning of the nineteenth century, Thomas Clarkson por- Atrayed the anti-slavery movement as a river of ideas that had swollen over time until it became an irrepressible torrent. Clarkson had no doubt that it had been the thought and action of all of those who, like Raynal, Benezet, and Wilberforce, had advocated “the cause of the injured Afri- cans” in Europe and in North America, which had ultimately lead to the abolition of the British slave trade, one of the first steps toward abolition of slavery itself.1 In our times, there are several views on what led to abolition and they all differ substantially from the river of ideas imagined by Clarkson. Iron- ically, for one of those views, it is as if Clarkson’s river had reversed its course and started to flow from its mouth to its source. Anyone who, for example, opens the UNESCO web page (the Slave Route project) will have access to an eloquent example of that approach, so radically opposed to Clarkson’s. In effect, one may read there that, “the first fighters for the abolition -

Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr

Copyright © 2013 by the National Trust for Historic Preservation i Table of Contents Letter from Erin Carlson Mast, Executive Director, President Lincoln’s Cottage Letter from Martin R. Castro, Chairman of The United States Commission on Civil Rights About President Lincoln’s Cottage, The National Trust for Historic Preservation, and The United States Commission on Civil Rights Author Biographies Acknowledgements 1. A Good Sleep or a Bad Nightmare: Tossing and Turning Over the Memory of Emancipation Dr. David Blight……….…………………………………………………………….….1 2. Abraham Lincoln: Reluctant Emancipator? Dr. Michael Burlingame……………………………………………………………….…9 3. The Lessons of Emancipation in the Fight Against Modern Slavery Ambassador Luis CdeBaca………………………………….…………………………...15 4. Views of Emancipation through the Eyes of the Enslaved Dr. Spencer Crew…………………………………………….………………………..19 5. Lincoln’s “Paramount Object” Dr. Joseph R. Fornieri……………………….…………………..……………………..25 6. Four Roads to Emancipation: Lincoln, the Law, and the Proclamation Dr. Allen Carl Guelzo……………..……………………………….…………………..31 7. Emancipation and its Complex Legacy as the Work of Many Hands Dr. Chandra Manning…………………………………………………..……………...41 8. The Emancipation Proclamation at 150 Dr. Edna Greene Medford………………………………….……….…….……………48 9. Lincoln, Emancipation, and the New Birth of Freedom: On Remaining a Constitutional People Dr. Lucas E. Morel…………………………….…………………….……….………..53 10. Emancipation Moments Dr. Matthew Pinsker………………….……………………………….………….……59 11. “Knock[ing] the Bottom Out of Slavery” and Desegregation: -

N the Changing Shape of Pro-Slavery Arguments in the Netherlands (1789- 1814)

3 n the changing shape of pro-slavery arguments in the Netherlands (1789- 1814) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320161402 Pepjin Brandon Department of History, VU Amsterdam International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, Netherlands [email protected] Abstract: One of the puzzling questions about the formal Dutch abolition of the slave- trade in 1814 is why a state that was so committed to maintaining slavery in its Empire did not put up any open resistance to the enforced closing of the trade that fed it. The explanations that historians have given so far for this paradox focus mainly on circumstances within the Netherlands, highlighting the pre-1800 decline of the role of Dutch traders in the African slave-trade, the absence of a popular abolitionist movement, and the all-overriding focus within elite-debates on the question of economic decline. This article argues that the (often partial) advanced made by abolitionism internationally did have a pronounced influence on the course of Dutch debates. This can be seen not only from the pronouncements by a small minority that advocated abolition, but also in the arguments produced by the proponents of a continuation of slavery. Careful examination of the three key debates about the question that took place in 1789-1791, 1797 and around 1818 can show how among dominant circles within the Dutch state a new ideology gradually took hold that combined verbal concessions to abolitionist arguments and a grinding acknowledgement of the inevitability of slave-trade abolition with a long-term perspective for prolonging slave-based colonial production in the West-Indies. -

ABOLITIONISTS and the CONSTITUTION Library of Congress/Theodore R

ABOLITIONISTS AND THE CONSTITUTION Library of Congress/Theodore R. Davis R. Congress/Theodore of Library The Constitution allowed Congress to ban the importation of slaves in 1808, but slave auctions, like the one pictured here, continued in southern states in the 19th century. Two great abolitionists, William Lloyd Garrison and deep-seated moral sentiments that attracted many Frederick Douglass, once allies, split over the Constitu- followers (“Garrisonians”), but also alienated many tion. Garrison believed it was a pro-slavery document others, including Douglass. from its inception. Douglass strongly disagreed. Garrison and Northern Secession Today, many Americans disagree about how to in- Motivated by strong, personal Christian convic- terpret the Constitution. This is especially true with our tions, Garrison was an uncompromising speaker and most controversial social issues. For example, Ameri- writer on the abolition of slavery. In 1831, Garrison cans disagree over what a “well-regulated militia” launched his own newspaper, The Liberator, in means in the Second Amendment, or whether the gov- Boston, to preach the immediate end of slavery to a ernment must always have “probable cause” under the national audience. In his opening editorial, he in- Fourth Amendment to investigate terrorism suspects. formed his readers of his then radical intent: “I will These kinds of disagreements about interpretation are not retreat a single inch, and I will be heard!” not new. In fact, they have flared up since the Consti- Garrison also co-founded the American Anti- tutional Convention in 1787. One major debate over the Slavery Society (AAS) in Boston, which soon had Constitution’s meaning caused a rift in the abolitionist over 200,000 members in several Northern cities.