Slave Revolts and the Abolition of Slavery: an Overinterpretation João Pedro Marques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

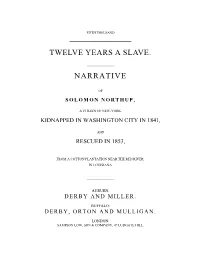

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries

History in the Making Volume 1 Article 7 2008 A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries Adam D. Wilsey CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Wilsey, Adam D. (2008) "A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries," History in the Making: Vol. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol1/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 78 CSUSB Journal of History A Study of West African Slave Resistance from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries Adam D. Wiltsey Linschoten, South and West Africa, Copper engraving (Amsterdam, 1596.) Accompanying the dawn of the twenty‐first century, there has emerged a new era of historical thinking that has created the need to reexamine the history of slavery and slave resistance. Slavery has become a controversial topic that historians and scholars throughout the world are reevaluating. In this modern period, which is finally beginning to honor the ideas and ideals of equality, slavery is the black mark of our past; and the task now lies History in the Making 79 before the world to derive a better understanding of slavery. In order to better understand slavery, it is crucial to have a more acute awareness of those that endured it. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

From African to African American: the Creolization of African Culture

From African to African American: The Creolization of African Culture Melvin A. Obey Community Services So long So far away Is Africa Not even memories alive Save those that songs Beat back into the blood... Beat out of blood with words sad-sung In strange un-Negro tongue So long So far away Is Africa -Langston Hughes, Free in a White Society INTRODUCTION When I started working in HISD’s Community Services my first assignment was working with inner city students that came to us straight from TYC (Texas Youth Commission). Many of these young secondary students had committed serious crimes, but at that time they were not treated as adults in the courts. Teaching these young students was a rewarding and enriching experience. You really had to be up close and personal with these students when dealing with emotional problems that would arise each day. Problems of anguish, sadness, low self-esteem, disappointment, loneliness, and of not being wanted or loved, were always present. The teacher had to administer to all of these needs, and in so doing got to know and understand the students. Each personality had to be addressed individually. Many of these students came from one parent homes, where the parent had to work and the student went unsupervised most of the time. In many instances, students were the victims of circumstances beyond their control, the problems of their homes and communities spilled over into academics. The teachers have to do all they can to advise and console, without getting involved to the extent that they lose their effectiveness. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads. -

The Slave's Cause: a History of Abolition

Civil War Book Review Summer 2016 Article 5 The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Corey M. Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Brooks, Corey M. (2016) "The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 18 : Iss. 3 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.18.3.06 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol18/iss3/5 Brooks: The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Review Brooks, Corey M. Summer 2016 Sinha, Manisha The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition. Yale University Press, $37.50 ISBN 9780300181371 The New Essential History of American Abolitionism Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause is ambitious in size, scope, and argument. Covering the entirety of American abolitionist history from the colonial era through the Civil War, Sinha, Professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, presents copious original research and thoughtfully and thoroughly mines the substantial body of recent abolitionist scholarship. In the process, Sinha makes a series of potent, carefully intertwined arguments that stress the radical and interracial dimensions and long-term continuities of the American abolitionist project. The Slave’s Cause portrays American abolitionists as radical defenders of democracy against countervailing pressures imposed both by racism and by the underside of capitalist political economy. Sinha goes out of her way to repudiate outmoded views of abolitionists as tactically unsophisticated utopians, overly sentimental romantics, or bourgeois apologists subconsciously rationalizing the emergent capitalism of Anglo-American “free labor" society. In positioning her work against these interpretations, Sinha may somewhat exaggerate the staying power of that older historiography, as most (though surely not all) current scholars in the field would likely concur wholeheartedly with Sinha’s valorization of abolitionists as freedom fighters who achieved great change against great odds. -

The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War By Richard S. Newman, Associate Professor of History Rochester Institute of Technology The Pennsylvania Abolition Society was the world's most famous antislavery group during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Indeed, although not as memorable as many later abolitionists (from William Lloyd Garrison and Lydia Maria Child to Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth), Pennsylvania reformers defined the antislavery movement for an entire generation of activists in the United States, Europe, and even the Caribbean. If you were an enlightened citizen of the Atlantic world following the American Revolution, then you probably knew about the PAS. Benjamin Franklin, a former slaveholder himself, briefly served as the organization's president. French philosophes corresponded with the organization, as did members of John Adams’ presidential Cabinet. British reformers like Granville Sharp reveled in their association with the PAS. It was, Sharp told told the group, an "honor" to be a corresponding member of so distinguished an organization.1 Though no supporter of the formal abolitionist movement, America’s “first man” George Washington certainly knew of the PAS's prowess, having lived for several years in the nation's temporary capital of Philadelphia during the 1790s. So concerned was the inaugural President with abolitionist agitation that Washington even shuttled a group of nine slaves back and forth between the Quaker State and his Mount Vernon home (still, two of his slaves escaped). The PAS was indeed a powerful abolitionist organization. PAS Origins The roots of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society date to 1775, when a group of mostly Quaker men met at a Philadelphia tavern to discuss antislavery measures. -

Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon

PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ALGERIA Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Tlemcen Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl; a Literary Weapon Against Slavery Dissertation submitted to the Department of English as a partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Literature and Civilization Presented by Supervised by Ms.Tasnim BELAIDOUNI Ms.Meriem MENGOUCHI BOARD OF EXAMINERS Dr. Wassila MOURO Chairwoman Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI Supervisor Dr. Frid DAOUDI Examiner Academic Year: 2016/2017 Dedications To those who believed in me To those who helped me through hard times To my Mother, my family and my friends I dedicate this work ii Acknowledgements Immense loads of gratitude and thanks are addressed to my teacher and supervisor Ms. Meriem MENGOUCHI; this work could have never come to existence without your vivacious guidance, constant encouragement, and priceless advice and patience. My sincerest acknowledgements go to the board of examiners namely; Dr. Wassila MOURO and Dr. Frid DAOUDI My deep gratitude to all my teachers iii Abstract Harriet Ann Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl seemed not to be the only literary work which tackled the issue of woman in slavery. However, this autobiography is the first published slave narrative written in the nineteenth century. In fact, the primary purpose of this research is to dive into Incidents in order to examine the author’s portrayal of a black female slave fighting for her freedom and her rights. On the other hand, Jacobs shows that despite the oppression and the persecution of an enslaved woman, she did not remain silent, but she strived to assert herself. -

Essay for Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument by Kate Clifford Larsen

From: Kate Clifford Larson, Ph.D. To: Cherie Butler, Superintendant, HATU; Aiden Smith, OAH Date: January 15, 2014 RE: HATU National Monument Scholars Roundtable White Paper Response In November 2013, the National Park Service invited five scholars to Dorchester County, Maryland to participate in a roundtable discussion about interpretation of Harriet Tubman’s life and legacy for the newly established Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument.1 Joining the scholars and NPS professionals, were representatives from Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge (BNWR), Maryland Department of Economic Development, the Organization of American Historians, local residents, and Haley Sharpe Design, the exhibit design firm. Initially guided by a set of questions framed by four themes - Building Communities, Anchoring the Spirit, Paths Toward Freedom and Resistance, and Sharing Knowledge - the discussion drew from the specialties and skill sets of each scholar, complimenting and enhancing each other’s ideas and perspectives while examining the core elements of Tubman’s life and legacy. One of the goals of the roundtable was to enhance NPS partnerships and collaborations with stakeholders and historians to ensure the incorporation of varied perspectives and views into innovative and challenging interpretation at NPS sites, particularly sites associated with controversial and emotionally charged subjects such as slavery and freedom at the Tubman National Monument. NPS, Maryland State Parks, and the Maryland -

The Many Images of Maroons Throughout the American South

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2003 "Father Wasn't De Onlies' One Hidin' in De Woods": The Many Images of Maroons Throughout the American South Angela Alicia Williams College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Angela Alicia, ""Father Wasn't De Onlies' One Hidin' in De Woods": The Many Images of Maroons Throughout the American South" (2003). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626383. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-35sn-v135 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FATHER WASN’TDE ONLIES’ ONE HIDIN’ INDE WOODS”: THE MANY IMAGES OF MAROONS THROUGHOUT THE AMERICAN SOUTH A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Angela Alicia Williams 2003 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts la Alicia Williams Approved by the Committee, December 2003 Grey Gundaker, Chair Richard Loj — \AAv-'—' Hermine Pinson For my mom. For my dad. For my family. For everyone who has helped me along my way. -

The Abolition of the British Slave Trade Sofía Muñoz Valdivieso (Málaga, Spain)

The Abolition of the British Slave Trade Sofía Muñoz Valdivieso (Málaga, Spain) 2007 marks the bicentenary of the Abolition of individual protagonists of the abolitionist cause, the Slave Trade in the British Empire. On 25 the most visible in the 2007 commemorations March 1807 Parliament passed an Act that put will probably be the Yorkshire MP William an end to the legal transportation of Africans Wilberforce, whose heroic fight for abolition in across the Atlantic, and although the institution Parliament is depicted in the film production of of slavery was not abolished until 1834, the 1807 Amazing Grace, appropriately released in Act itself was indeed a historic landmark. Britain on Friday, 23 March, the weekend of Conferences, exhibitions and educational the bicentenary. The film reflects the traditional projects are taking place in 2007 to view that places Wilberforce at the centre of commemorate the anniversary, and many the antislavery process as the man who came different British institutions are getting involved to personify the abolition campaign (Walvin in an array of events that bring to public view 157), to the detriment of other less visible but two hundred years later not only the equally crucial figures in the abolitionist parliamentary process whereby the trading in movement, such as Thomas Clarkson, Granville human flesh was made illegal (and the Sharp and many others, including the black antislavery campaign that made it possible), but voices who in their first-person accounts also what the Victoria and Albert Museum revealed to British readers the cruelty of the exhibition calls the Uncomfortable Truths of slave system. -

N the Changing Shape of Pro-Slavery Arguments in the Netherlands (1789- 1814)

3 n the changing shape of pro-slavery arguments in the Netherlands (1789- 1814) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320161402 Pepjin Brandon Department of History, VU Amsterdam International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, Netherlands [email protected] Abstract: One of the puzzling questions about the formal Dutch abolition of the slave- trade in 1814 is why a state that was so committed to maintaining slavery in its Empire did not put up any open resistance to the enforced closing of the trade that fed it. The explanations that historians have given so far for this paradox focus mainly on circumstances within the Netherlands, highlighting the pre-1800 decline of the role of Dutch traders in the African slave-trade, the absence of a popular abolitionist movement, and the all-overriding focus within elite-debates on the question of economic decline. This article argues that the (often partial) advanced made by abolitionism internationally did have a pronounced influence on the course of Dutch debates. This can be seen not only from the pronouncements by a small minority that advocated abolition, but also in the arguments produced by the proponents of a continuation of slavery. Careful examination of the three key debates about the question that took place in 1789-1791, 1797 and around 1818 can show how among dominant circles within the Dutch state a new ideology gradually took hold that combined verbal concessions to abolitionist arguments and a grinding acknowledgement of the inevitability of slave-trade abolition with a long-term perspective for prolonging slave-based colonial production in the West-Indies.