The PAS and American Abolitionism: a Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Puritan Pedagogy in Uncle Tom's Cabin

Molly Dying Instruction: Puritan Pedagogy in Farrell Uncle Tom’s Cabin To day I have taken my pen from the last chapter of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” . It has been the most cheering thing about the whole endeavor to me, that men like you, would feel it. —Letter from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Horace Mann, 2 March 1852 n 1847, three years before Harriet Beecher Stowe I began Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Horace Mann and his wife Mary offered Miss Chloe Lee, a young black student who had been admitted to the Normal School in West Newton, the spare room in their Massachusetts home.1 Mann had recently been corresponding with Stowe’s sister Catherine Beecher about their shared goals for instituting a new kind of edu- cation that would focus more on morals than on classical knowledge and would target the entire society. Beecher enthusiastically asserted that with this inclusive approach, she had “no hesitation in saying, I do not believe that one, no, not a single one, would fail of proving a respectable and prosperous member of society.”2 There were no limits to who could be incorporated into their educational vision—a mission that would encompass even black students like Lee. Arising from the evangelical tradition of religious teaching, these educators wanted to change the goal of the school from the preparation of leaders to the cultivation of citizens. This work of acculturation—making pedagogy both intimate and all-encompassing—required educators to replace the role of parents and turn the school into a multiracial family. Stowe and her friends accordingly had to imagine Christian instruction and cross-racial connection as intimately intertwined. -

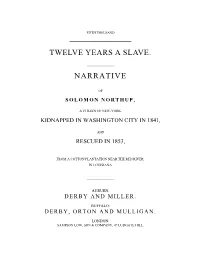

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

The End of Uncle Tom

1 THE END OF UNCLE TOM A woman, her body ripped vertically in half, introduces The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven from 1995 (figs.3 and 4), while a visual narra- tive with both life and death at stake undulates beyond the accusatory gesture of her pointed finger. An adult man raises his hands to the sky, begging for deliverance, and delivers a baby. A second man, obese and legless, stabs one child with his sword while joined at the pelvis with another. A trio of children play a dangerous game that involves a hatchet, a chopping block, a sharp stick, and a bucket. One child has left the group and is making her way, with rhythmic defecation, toward three adult women who are naked to the waist and nursing each other. A baby girl falls from the lap of one woman while reaching for her breast. With its references to scatology, infanticide, sodomy, pedophilia, and child neglect, this tableau is a troubling tribute to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin—the sentimental, antislavery novel written in 1852. It is clearly not a straightfor- ward illustration, yet the title and explicit references to racialized and sexualized violence on an antebellum plantation leave little doubt that there is a significant relationship between the two works. Cut from black paper and adhered to white gallery walls, this scene is composed of figures set within a landscape and depicted in silhouette. The medium is particularly apt for this work, and for Walker’s project more broadly, for a number of reasons. -

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: the Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865

Black Citizenship, Black Sovereignty: The Haitian Emigration Movement and Black American Politics, 1804-1865 Alexander Campbell History Honors Thesis April 19, 2010 Advisor: Françoise Hamlin 2 Table of Contents Timeline 5 Introduction 7 Chapter I: Race, Nation, and Emigration in the Atlantic World 17 Chapter II: The Beginnings of Black Emigration to Haiti 35 Chapter III: Black Nationalism and Black Abolitionism in Antebellum America 55 Chapter IV: The Return to Emigration and the Prospect of Citizenship 75 Epilogue 97 Bibliography 103 3 4 Timeline 1791 Slave rebellion begins Haitian Revolution 1831 Nat Turner rebellion, Virginia 1804 Independent Republic of Haiti declared, Radical abolitionist paper The Liberator with Jean-Jacques Dessalines as President begins publication 1805 First Constitution of Haiti Written 1836 U.S. Congress passes “gag rule,” blocking petitions against slavery 1806 Dessalines Assassinated; Haiti divided into Kingdom of Haiti in the North, Republic of 1838 Haitian recognition brought to U.S. House Haiti in the South. of Representatives, fails 1808 United States Congress abolishes U.S. 1843 Jean-Pierre Boyer deposed in coup, political Atlantic slave trade chaos follows in Haiti 1811 Paul Cuffe makes first voyage to Africa 1846 Liberia, colony of American Colonization Society, granted independence 1816 American Colonization Society founded 1847 General Faustin Soulouque gains power in 1817 Paul Cuffe dies Haiti, provides stability 1818 Prince Saunders tours U.S. with his 1850 Fugitive Slave Act passes U.S. Congress published book about Haiti Jean-Pierre Boyer becomes President of 1854 Martin Delany holds National Emigration Republic of Haiti Convention Mutiny of the Holkar 1855 James T. -

Dramatizing the Sura of Joseph: an Introduction to the Islamic Humanities

Dramatizing the Sura of Joseph: An introduction to the Islamic humanities Author: James Winston Morris Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/4235 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Published in Journal of Turkish Studies, vol. 18, pp. 201-224, 1994 Use of this resource is governed by the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons "Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States" (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/) Dramatizing the Sura ofJoseph: An Introduction to the Islamic Humanities. In Annemarie Schimmel Festschrift, special issue of Journal of Turkish Studies (H8lVard), vol. 18 (1994), pp. 20\·224. Dramatizing the Sura of Joseph: An Introduction to the Islamic Humanities. In Annemarie Schimmel Festschrift, special issue of Journal of Turkish Studies (Harvard), vol. 18 (1994), pp. 201-224. DRAMATIZING THE SURA OF JOSEPH: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ISLAMIC HUMANITIES James W. Morris J "Surely We are recounting 10 you the most good-and-beautiful of laJes ...." (Qur'an. 12:3) Certainly no other scholar ofher generation has dooe mae than Annemarie Schimmel to ilIwninal.e the key role of the Islamic hwnanities over the centuries in communicating and bringing alive for Muslims the inner meaning of the Quru and hadilh in 30 many diverse languages and cultural settings. Long before a concern with '"populal'," oral and ve:macul.- religious cultures (including tKe lives of Muslim women) had become so fashK:inable in religious and bi.storica1 studies. Professor Scbimmel's anicJes and books were illuminating the ongoing crutive expressions and transfonnalions fA Islamic perspectives in both written and orallilrnblr'es., as well as the visual ar:1S, in ways tba have only lllCentIy begun 10 make their war into wider scholarly and popular understandings of the religion of Islam. -

I C U: 35 Days to Revive My Faith

I C U: 35 Days to Revive My Faith Revelation 3:20 tells us that Jesus not only came to redeem us 2000 years ago, but every day pursues us - personally, persistently. Over the next 5 weeks, we will take a few minutes every day to open the door again to the work of God in our lives. Outside of the work on the cross and the empty tomb on the third day, God has given us another incredible gift: the gift of His word. It is through His word, the Bible, that God continues to speak, revive, and restore broken lives, dreams, and souls. I invite you to set aside 15 minutes, 5 days a week to open the door again to the work of God. Suggested daily outline: read 2 Timothy 3:16-17, pray, read the devotional, write a simple response to the devotional, and work on the weekly memory verse throughout the day ___________________ Week Five Sermon -- Making the Broken Pieces Fit: Dinah This week’s emphasis: Multiplying in Another (Coaching) Day One Read Luke 1:1-66 Elizabeth to Mary When you are “greatly troubled” do you have other believers you can open up to? Mary ran to Elizabeth, who was a truth teller in her life: “blessed are you!” Do you have someone in your life that can help you see the blessing through your troubles? It is important to find others who can lovingly walk through life with you, impart wisdom, truth, and remind you of God’s purpose and plan in your life, especially when you are under stress. -

CT Elijah Anderson, VA

William Hargis (Elizabeth Joy), NC A Henry Holladay/Holliday (Mary Fayle/Faile), NC James Adams (Edna Allyn), CT Samuel Hudgins (Elizabeth Lanier), VA Elijah Anderson, VA I B Joseph Ingalls (Ruby Norton), MA Henry Bale (Elizabeth Gunderman), NJ Benjamin Ishmael (Jane), PA John/Johannes Bellinger (Maria Magdalena Klock), NY Christen Bower (Elizabeth), PA Richard Briggs, MA Peter Brown, NY & PA K John Kennedy (Esther Stilly), VA C Asa Kitchell (Rhoda Baldwin), NJ Dempsey Capp/Capps (Sarah Pool Overman), NC James Carr, NC, CAPT Thomas Clark, NC James Coachman, SC L George Edwards Cordell, VA PS John Lockridge/Loughridge (Margaret Henderson), VA James Courtney, VA Joseph Long (Elizabeth Myers), MD Joseph Crane, NJ Christopher Loving, SC D M George Damron (Susannah Thomas), VA Andrew Mann (Rachel Egnor), PA Richard Davenport (Rebecca Johnston), VA Peleg Matteson (Barbara Bowen), VT James Davidson/Davison (Elinor Stinson), NJ Elijah Mayfield (Elizabeth), VA Peter Derry, MD Jonathan McNeil, VA Elisha Dodson (Sarah Evertt), VA Isham Meader (Biddy Bradshaw), VA William Duvall (Priscilla Prewitt), MD Jeptha Merrill (Mary Royce), CT John Mills (Frances Hall), VA E Roger Enos (Jerusha Hayden), CT & VT P Henry Parrish (Mary Ann Monk), NC F Joel Parish ( Mary (Woolfolk), VA William Penney, NC CAPT CS Samuel Foster (Mary Mayhall Veach), VA &PA William Penney (Elizabeth Barkley), NC George Fruits, Jr. (Catherine Stonebraker), PA Jonathan Purcell, VA Benjamin Purdy Jr. (Elizabeth Bullis), VT G Philip Gatch, VA, PS R John Greider (Isabelle Blair), NC John Reagan, NC, CAPT William Mccale, SC PVT PS Isaiah Guymon (Elizabeth Flynn), NC Casper Reed, Jr. (Anna), PA Henry Rhodes/Rhodes (Elizabeth Stoner), PA John Richardson (Mary Terrell), H Frederick Ripperdan (Sarah Chiticks), VA Caleb Halsted, Sr. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism. -

Abolitionist Movement

Abolitionist Movement The goal of the abolitionist movement was the immediate emancipation of all slaves and the end of racial discrimination and segregation. Advocating for immediate emancipation distinguished abolitionists from more moderate anti-slavery advocates who argued for gradual emancipation, and from free-soil activists who sought to restrict slavery to existing areas and prevent its spread further west. Radical abolitionism was partly fueled by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening, which prompted many people to advocate for emancipation on religious grounds. Abolitionist ideas became increasingly prominent in Northern churches and politics beginning in the 1830s, which contributed to the regional animosity between North and South leading up to the Civil War. The Underground Railroad c.1780 - 1862 The Underground Railroad, a vast network of people who helped fugitive slaves escape to the North and to Canada, was not run by any single organization or person. Rather, it consisted of many individuals -- many whites but predominantly black -- who knew only of the local efforts to aid fugitives and not of the overall operation. Still, it effectively moved hundreds of slaves northward each year -- according to one estimate, the South lost 100,000 slaves between 1810 and 1850. Still, only a small percentage of escaping slaves received assistance from the Underground Railroad. An organized system to assist runaway slaves seems to have begun towards the end of the 18th century. In 1786 George Washington complained about how one of his runaway slaves was helped by a "society of Quakers, formed for such purposes." The system grew, and around 1831 it was dubbed "The Underground Railroad," after the then emerging steam railroads. -

The Slave's Cause: a History of Abolition

Civil War Book Review Summer 2016 Article 5 The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Corey M. Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Brooks, Corey M. (2016) "The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 18 : Iss. 3 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.18.3.06 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol18/iss3/5 Brooks: The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition Review Brooks, Corey M. Summer 2016 Sinha, Manisha The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition. Yale University Press, $37.50 ISBN 9780300181371 The New Essential History of American Abolitionism Manisha Sinha’s The Slave’s Cause is ambitious in size, scope, and argument. Covering the entirety of American abolitionist history from the colonial era through the Civil War, Sinha, Professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, presents copious original research and thoughtfully and thoroughly mines the substantial body of recent abolitionist scholarship. In the process, Sinha makes a series of potent, carefully intertwined arguments that stress the radical and interracial dimensions and long-term continuities of the American abolitionist project. The Slave’s Cause portrays American abolitionists as radical defenders of democracy against countervailing pressures imposed both by racism and by the underside of capitalist political economy. Sinha goes out of her way to repudiate outmoded views of abolitionists as tactically unsophisticated utopians, overly sentimental romantics, or bourgeois apologists subconsciously rationalizing the emergent capitalism of Anglo-American “free labor" society. In positioning her work against these interpretations, Sinha may somewhat exaggerate the staying power of that older historiography, as most (though surely not all) current scholars in the field would likely concur wholeheartedly with Sinha’s valorization of abolitionists as freedom fighters who achieved great change against great odds. -

American Free Blacks and Emigration to Haiti

#33 American Free Blacks and Emigration to Haiti by Julie Winch University of Massachusetts, Boston Paper prepared for the XIth Caribbean Congress, sponsored by the Caribbean Institute and Study Center for Latin America (CISCLA) of Inter American University, the Department of Languages and Literature of the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, and the International Association of Comparative Literature, held in Río Piedras March 3 and 5, in San Germán March 4, 1988 August 1988 El Centro de Investigaciones Sociales del Caribe y América Latina (CISCLA) de la Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico, Recinto de San Germán, fue fundado en 1961. Su objetivo fundamental es contribuir a la discusión y análisis de la problemática caribeña y latinoamericana a través de la realización de conferencias, seminarios, simposios e investigaciones de campo, con particular énfasis en problemas de desarrollo político y económico en el Caribe. La serie de Documentos de Trabajo tiene el propósito de difundir ponencias presentadas en actividades de CISCLA así como otros trabajos sobre temas prioritarios del Centro. Para mayor información sobre la serie y copias de los trabajos, de los cuales existe un número limitado para distribución gratuita, dirigir correspondencia a: Dr. Juan E. Hernández Cruz Director de CISCLA Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico Apartado 5100 San Germán, Puerto Rico 00683 The Caribbean Institute and Study Center for Latin America (CISCLA) of Inter American University of Puerto Rico, San Germán Campus, was founded in 1961. Its primary objective is to make a contribution to the discussion and analysis of Caribbean and Latin American issues. The Institute sponsors conferences, seminars, roundtable discussions and field research with a particular emphasis on issues of social, political and economic development in the Caribbean. -

Benjamin Franklin on Printers' Choice

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox Becoming American: The British Atlantic Colonies, 1690-1763 The Franklin Institute BENJAMIN FRANKLIN on Printers’ Choice & Press Freedom * Two editorials in The Pennsylvania Gazette, 1731, 1740 ___________________________________________________ “Apology for Printers” The Pennsylvania Gazette, 10 June 1731, excerpts After being criticized for printing a ship captain’s advertisement that excluded clergymen as passengers, local clergy threatened to boycott the Gazette and take no printing jobs to Franklin.1 Due to the resulting clamor, Franklin published this “apology,” i.e., a statement of his philoso- phy as a printer, and concludes by explaining how and why he printed the offending handbill and why he should not be censured for the act. Slug mold (~10 in.)., into which hot lead is poured to create "slugs" of metal from which individual characters (letters, numerals, etc.) can be made Being frequently censur’d and condemn’d by different Persons for printing Things which they say ought not to be Tools of the printing trade printed, I have sometimes thought it might be necessary to make a standing Apology for myself and publish it once a Year, to be read upon all Occasions of that Nature. Much Business has hitherto hindered the execution of this Design [plan], but having very lately given extraordinary Offense by printing an Advertisement with a certain N.B.2 at the End of it, I find an Apology more particularly requisite at this Juncture . I request all who are angry with me on the Account of printing things they don’t like, calmly to consider these following Particulars 1.