Slavery and Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captivity and Identity in Aphra Behn's Oroonoko Or, the Royal Slave

وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث العلمي MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE جامعة مولود معمري - تيزي وزو UNIVERSITE MOULOUD MAMMERI DE TIZI-OUZOU كلية اﻵداب واللغات FACULTE DES LETTRES ET DES LANGUES DEPARTEMENT D’ANGLAIS Domaine : Lettres et Langues Etrangères. Filière : Langue Anglaise. Spécialité: Media and Cultural Studies. Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in English Captivity and Identity in Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko or, The Royal Slave (1688) and Penelope Aubin’s The Noble Slaves (1722). Presented by: Supervised by:Mrs.Kahina LEGOUI Djamila BOUAZIZ Karima RAIAH Board of Examiners: Mrs. Tabti Kahina, M. A. A, Department of English, Chair. Mrs. Abdelli Fatima, M. A. A, Department of English, Examiner. Mrs. Legoui Kahina, M.A.A, Department of English, Supervisor Promotion: December 2016 N° d’Ordre : …………… N° de série : …………… Laboratoire de domiciliation du master: Etudes des Langues et Cultures Etrangères. To: my dear parents Ali and Baya my dear brother Salim my dear sister Houria my best friends Djamila To: my dear parents Said and Djouher my dear brothers especially Mouloud my dear sisters my best friends Karima I Acknowledgements We would like to thank our supervisor Mrs. LEGOUI for her precious help and assistance in the realization of this dissertation. We would like also to thank our teachers for their guidance and advice all along the academic year and for all the teachings they provided us with. Special thanks must go to our parents and our friends who have provided us with moral support and encouragement. II Content Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………….………I Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………IV I. -

BLACK WOMEN ARE LEADERS Long Form

BLACK WOMEN ARE LEADERS IN THE MOVEMENT TO END SEXUAL & DOMESTIC VIOLENCE Ida B. Wells The Combahee River Collective Wells, a suffragist and temperance activist, famously and fearlessly This Boston-based collective spoke against lynchings, and also of black feminist lesbians worked to end sexual violence wrote the seminal essay The against black women. Radically, Combahee River Collective Wells identified scapegoating of Statement, centering black black men as rapists as a projection feminist issues and identifying of white men's own history of sexual white feminism as an entity violence, often enacted against black that often excludes or women. sidelines black women. They campaigned against sexual assault in their communities and raised awareness of the racialized sexual Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw violence that black women face. A legal scholar, writer, and activist, Crenshaw famously coined the term Loretta Ross "intersectionality," forever impacting An academic, activist, and writer, the way we think about social identity. Ros s has written extensively on Crenshaw's work draws attention to the topic of reproductive justice the fact that black women exist at the and is a pioneer of reproductive intersection of multiple oppressions justice theory. Her work has and experience the dual violence of brought attention to the ways both racism and misogyny. reproductive coercion, racism, and sexual violence intersect. Harriet Jacobs Tarana Burke Jacobs was born into An activist and public speaker, Burke slavery and sex ually founded the wildly successful assaulted by her owner, #MeToo movement. Specifically and eventually escaped created to highlight violence by hiding undetected in experienced by marginalized an attic for seven years. -

Hermaphrodite Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams

Philosophies of Sex Etching of Julia Ward Howe. By permission of The Boston Athenaeum hilosophies of Sex PCritical Essays on The Hermaphrodite EDITED BY RENÉE BERGLAND and GARY WILLIAMS THE OHIO State UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Philosophies of sex : critical essays on The hermaphrodite / Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1189-2 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1189-5 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9290-7 (cd-rom) 1. Howe, Julia Ward, 1819–1910. Hermaphrodite. I. Bergland, Renée L., 1963– II. Williams, Gary, 1947 May 6– PS2018.P47 2012 818'.409—dc23 2011053530 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Minion Pro and Scala Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction GARY Williams and RENÉE Bergland 1 Foreword Meeting the Hermaphrodite MARY H. Grant 15 Chapter One Indeterminate Sex and Text: The Manuscript Status of The Hermaphrodite KAREN SÁnchez-Eppler 23 Chapter Two From Self-Erasure to Self-Possession: The Development of Julia Ward Howe’s Feminist Consciousness Marianne Noble 47 Chapter Three “Rather Both Than Neither”: The Polarity of Gender in Howe’s Hermaphrodite Laura Saltz 72 Chapter Four “Never the Half of Another”: Figuring and Foreclosing Marriage in The Hermaphrodite BetsY Klimasmith 93 vi • Contents Chapter Five Howe’s Hermaphrodite and Alcott’s “Mephistopheles”: Unpublished Cross-Gender Thinking JOYCE W. -

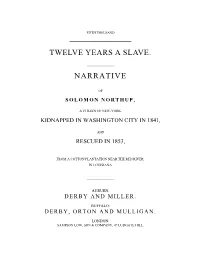

Twelve Years a Slave. Narrative

FIFTH THOUSAND TWELVE YEARS A SLAVE. NARRATIVE OF SOLOMON NORTHUP, A CITIZEN OF NEW-YORK, KIDNAPPED IN WASHINGTON CITY IN 1841, AND RESCUED IN 1853, FROM A COTTON PLANTATION NEAR THE RED RIVER, IN LOUISIANA. AUBURN: DERBY AND MILLER. BUFFALO: DERBY, ORTON AND MULLIGAN. LONDON: SAMPSON LOW, SON & COMPANY, 47 LUDGATE HILL. 1853. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year one thousand eight hundred and fifty-three, by D E R B Y A N D M ILLER , In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Northern District of New-York. ENTERED IN LONDON AT STATIONERS' HALL. TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED "Such dupes are men to custom, and so prone To reverence what is ancient, and can plead A course of long observance for its use, That even servitude, the worst of ills, Because delivered down from sire to son, Is kept and guarded as a sacred thing. But is it fit, or can it bear the shock Of rational discussion, that a man Compounded and made up, like other men, Of elements tumultuous, in whom lust And folly in as ample measure meet, As in the bosom of the slave he rules, Should be a despot absolute, and boast Himself the only freeman of his land?" Cowper. [Pg vii] CONTENTS. PAGE. EDITOR'S PREFACE, 15 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Ancestry—The Northup Family—Birth and Parentage—Mintus Northup—Marriage with Anne Hampton—Good Resolutions—Champlain Canal—Rafting Excursion to Canada— Farming—The Violin—Cooking—Removal to Saratoga—Parker and Perry—Slaves and Slavery— The Children—The Beginning of Sorrow, 17 CHAPTER II. -

Defying Conventions and Highlighting Performance 49

Defying Conventions and Highlighting Performance Within and Beyond Slavery in William Wells Brown's Clotel Eileen Moscoso English Faculty advisor: Lori Leavell As an introduction to his novel, Clotel or, The President's Daughter, William Wells Brown, an African American author and fugitive slave, includes a shortened and revised version of his autobiographical narrative titled “Narrative of the Life and Escape of William Wells Brown” (1853). African American authors in the nineteenth century often feared the skepticism they would undoubtedly receive from white readers. Therefore, in order to broaden their readership and gain a more trusting audience, African American authors routinely sought a more socially accepted and allegedly credible person, namely a white American, to authenticate their writing in the preface. Brown boldly refuses to adhere to this convention in an effort to rid his white readership of their assumptions of black inferiority. Rather, he authorizes himself. My paper illuminates Brown's defiance of authorship conventions as an act of resistance rooted in performance, one that strategically parallels other forms of resistance that take place in his literary representations of the plantation. I argue that all counts of trickery enacted by Brown can be better understood when related to the role CLA Journal 1 (2013) pp. 48-58 Defying Conventions and Highlighting Performance 49 _____________________________________________________________ of performance on the plantation. Quite revolutionarily, William Wells Brown uses his own words in the introduction to validate his authorship rather than relying on a more ostensibly qualified figure's. As bold a move that may be, Brown does so with a layer of trickery that allows it to go potentially undetected by the reader. -

The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2006 Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction Miya G. Abbot University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Abbot, Miya G., "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1487 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. Abbot entitled "Dismantling the Master’s Schoolhouse: The Rhetoric of Education in African American Autobiography and Fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of , with a major in English. Miriam Thaggert, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mary Jo Reiff, Janet Atwill Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Miya G. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

In Memoriam Frederick Dougla

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection CANNOT BE PHOTOCOPIED * Not For Circulation Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection / III llllllllllll 3 9077 03100227 5 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection jFrebericfc Bouglass t Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection fry ^tty <y /z^ {.CJ24. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Hn flDemoriam Frederick Douglass ;?v r (f) ^m^JjZ^u To live that freedom, truth and life Might never know eclipse To die, with woman's work and words Aglow upon his lips, To face the foes of human kind Through years of wounds and scars, It is enough ; lead on to find Thy place amid the stars." Mary Lowe Dickinson. PHILADELPHIA: JOHN C YORSTON & CO., Publishers J897 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Copyright. 1897 & CO. JOHN C. YORSTON Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection 73 7^ In WLzmtxtrnm 3fr*r**i]Ch anglais; "I have seen dark hours in my life, and I have seen the darkness gradually disappearing, and the light gradually increasing. One by one, I have seen obstacles removed, errors corrected, prejudices softened, proscriptions relinquished, and my people advancing in all the elements I that make up the sum of general welfare. remember that God reigns in eternity, and that, whatever delays, dis appointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty and humanity will prevail." Extract from address of Mr. -

Civilization and Sexual Abuse: Selected Indian Captivity Narratives and the Native American Boarding-School Experience

................................................................................................................. CROSSROADS. A Journal of English Studies 27 (2019) EWA SKAŁ1 DOI: 10.15290/CR.2019.27.4.05 University of Opole ORCID: 0000-0001-7550-3292 Civilization and sexual abuse: selected Indian captivity narratives and the Native American boarding-school experience Abstract. This paper offers a contrastive analysis of Indian captivity narratives and the Native American boarding-school experience. Indian captivity narratives describe the ordeals of white women and men, kidnapped by Indians, who were separated from their families and subsequently lived months or even years with Indian tribes. The Native American boarding-school experience, which began in the late nineteenth century, took thousands of Indian children from their parents for the purpose of “assimi- lation to civilization” to be facilitated through governmental schools, thereby creating a captivity of a different sort. Through an examination of these two different types of narratives, this paper reveals the themes of ethnocentrism and sexual abuse, drawing a contrast that erodes the Euro-American discourse of civilization that informs captivity narratives and the boarding-school, assimilationist experiment. Keywords: Native Americans, captivity narratives, boarding schools, sexual abuse, assimilation. 1. Introduction Comparing Indian captivity narratives and writings on the Native American board- ing- school experience is as harrowing as it is instructive. Indian captivity narratives, mostly dating from 1528 to 1836, detail the ordeals of white, Euro-American women and men kidnapped by Native peoples. Separated from their families and white “civili- zation,” they subsequently lived for a time among Indian tribes. Such narratives can be seen as a prelude to a sharp reversal that occurred in the late nineteenth century under U.S. -

Teen Stabbing Questions Still Unanswered What Motivated 14-Year-Old Boy to Attack Family?

Save $86.25 with coupons in today’s paper Penn State holds The Kirby at 30 off late Honoring the Center’s charge rich history and its to beat Temple impact on the region SPORTS • 1C SPECIAL SECTION Sunday, September 18, 2016 BREAKING NEWS AT TIMESLEADER.COM '365/=[+<</M /88=C6@+83+sǍL Teen stabbing questions still unanswered What motivated 14-year-old boy to attack family? By Bill O’Boyle Sinoracki in the chest, causing Sinoracki’s wife, Bobbi Jo, 36, ,9,9C6/Ľ>37/=6/+./<L-97 his death. and the couple’s 17-year-old Investigators say Hocken- daughter. KINGSTON TWP. — Specu- berry, 14, of 145 S. Lehigh A preliminary hearing lation has been rampant since St. — located adjacent to the for Hockenberry, originally last Sunday when a 14-year-old Sinoracki home — entered 7 scheduled for Sept. 22, has boy entered his neighbors’ Orchard St. and stabbed three been continued at the request house in the middle of the day members of the Sinoracki fam- of his attorney, Frank Nocito. and stabbed three people, kill- According to the office of ing one. ily. Hockenberry is charged Magisterial District Justice Everyone connected to the James Tupper and Kingston case and the general public with homicide, aggravated assault, simple assault, reck- Township Police Chief Michael have been wondering what Moravec, the hearing will be lessly endangering another Photo courtesy of GoFundMe could have motivated the held at 9:30 a.m. Nov. 7 at person and burglary in connec- In this photo taken from the GoFundMe account page set up for the Sinoracki accused, Zachary Hocken- Tupper’s office, 11 Carverton family, David Sinoracki is shown with his wife, Bobbi Jo, and their three children, berry, to walk into a home on tion with the death of David Megan 17; Madison, 14; and David Jr., 11. -

Can Words Lead to War?

Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Full-page illustration from first edition Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Hammatt Billings. Available in Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture. Supporting Questions 1. How did Harriet Beecher Stowe describe slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 2. What led Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 3. How did northerners and southerners react to Uncle Tom’s Cabin? 4. How did Uncle Tom’s Cabin affect abolitionism? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 Middle School Uncle Tom’s Cabin Inquiry Can Words Lead to War? Framework for Summary Objective 12: Students will understand the growth of the abolitionist movement in the Teaching American 1830s and the Southern view of the movement as a physical, economic and political threat. Slavery Consider the power of words and examine a video of students using words to try to bring about Staging the Question positive change. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Supporting Question 4 How did Harriet Beecher What led Harriet Beecher How did people in the How did Uncle Tom’s Stowe describe slavery in Stowe to write Uncle North and South react to Cabin affect abolitionism? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Tom’s Cabin? Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Formative Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Complete a source analysis List four quotes from the Make a T-chart comparing Participate in a structured chart to write a summary sources that point to the viewpoints expressed discussion regarding the of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that Stowe’s motivation and in northern and southern impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin includes main ideas and write a paragraph newspaper reviews of had on abolitionism.