Working Paper 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Searchable PDF Format

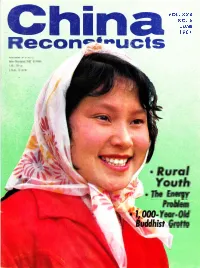

vo[. xxx NO. 6 JUNE r98r R Austraha: ASt) 72 Neu Zealand: NZ $ 0.t14 UK:39 p US.A:S0.7ti o Rurql Youth o lhe EnqgY Prcilm Yeor-Old Grollo China's first high-l1ux nuclear reactor goes into operation. Here, the !:eactor core is being installed. Plrrtto hr Liu l.ltibin PUBLISHED MONTHTY IN ENGLISH, FRENCH, SPANISH, AMBIC, GERMAN, PORTUGUESE AND CHINESE BY THE CHINA TYETFARE INSNTUTE (sOONG CHING LINg, CHAIRMANI vor. xxx No. 6 JUNE 1981 Articles of the Month CONTENTS Young Folks in the Country Villoge Youth Young People of a Rural Brigade E Eighty percent of Chino's young people live in the o The Youth Experimental Farm B countryside. A series describes their current mood o Into the World Market 1.1 os they work to chonge the foce of Chino. Poge 5 o More Marriages in Zhongshahai 13 Econonny/Science China's First High-Flux Reactor 5B The Making of a Young Science Writer 56 Saving Energy for More Production 34 The Xiamen Special Economic Zone 68 Stockbreeding The Horse of the Future-and the Past 16 Culture/Arts The Energy Problem National Exhibition by Young Artists 30 Xiao Youmei, Pioneer in Music Education 24 lndustriol production rcse 8.4/" in 1980 while output The Dazu Treasure-House of Carvings 50 of energy declilned slightly. Conservotion, energy Engraving on a Human Hair 43 etficiency, ond new lesources ore the onswer. The Art of Miniature 42 Poge 3l ln Guangzhou's Orchid Garden hz s Educotion The Youth A* Erhibition The Overseas Chinese University 18 Friendship How some of Grino's best yoring Memories of Chin.a 40 ortists tockle new themes ond new YMCA Seminar Tour from U.S. -

The Communist Party of China: I • Party Powers and Group Poutics I from the Third Plenum to the Twelfth Party Congress

\ 1 ' NUMBER 2- 1984 (81) NUMBER 2 - 1984 (81) THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF CHINA: I • PARTY POWERS AND GROUP POUTICS I FROM THE THIRD PLENUM TO THE TWELFTH PARTY CONGRESS Hung-mao Tien School of LAw ~ of MAaylANCI • ' Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: Mitchell A. Silk Managing Editor: Shirley Lay Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor Lawrence W. Beer, Lafayette College Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Professor Gottfried-Karl Kindermann, Center for International Politics, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Professor Choon-ho Park, College of Law and East Asian Law of the Sea Institute, Korea University, Republic of Korea Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion contained therein. Subscription is US $10.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $12.00 for overseas. -

The 16Th Party Congress: a Preview

Fewsmith, China Leadership Monitor, No.4 The 16th Party Congress: A Preview Joseph Fewsmith The 16th Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will convene November 8, 2002. It and the First Plenary Session of the 16th Central Committee that will immediately follow the congress will overhaul China’s top leadership, including the Central Committee, the Politburo, the Politburo Standing Committee, the secretariat, and the CCP’s Central Military Commission. The congress will also revise the CCP’s party charter--to what extent and in what way will be watched closely--and issue a political report, which will review the party’s achievements and amend its ideology. Although much anticipated, this party congress is unlikely to provide a sharp turning point in party policy. The influence of Jiang Zemin and/or his close supporters will persist. The political transition many are hoping for is likely to be drawn out, perhaps extending to the 17th Party Congress in 2007. The 16th Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, scheduled to convene November 8, 2002, has attracted a great deal of attention, because if power is peacefully transferred to a new generation, it will be the first time this feat has been accomplished in the history of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). However, the rumor mill has been working overtime in recent months, and speculation has been rife over whether CCP General Secretary Jiang Zemin will retire and what personnel arrangements will be made.1 This article cannot answer these questions directly, but it can lay out in broad terms what the party congress can be expected to do and which issues have been discussed in party publications in recent months. -

ELITE CONFLICT in the POST-MAO CHINA (Revised Edition 1983)

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiEs iN CoNTEMpoRARY • • AsiAN STudiEs - NUMBER 2 - 1983 (55) ELITE CONFLICT IN THE POST-MAO CHINA I • (Revised edition) •• Parris H. Chang School of LAw UNivERSiTy of 0 •• MARylANd~ c::;. ' 0 Occasional Papers/Reprint Series in Contemporary Asian Studies General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editor: David Salem Managing Editor: Shirley Lay Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor Lawrence W. Beer, Lafayette College Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Robert Heuser, Max-Planck-Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law at Heidelberg Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor K. P. Misra, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International La~ Society All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion contained therein. Subscription is US $10.00 for 6 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $12.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

1/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 45 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 50 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 54 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 57 Taiwan Political LIU JEN-KAI 59 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 61 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 1/2006 The Leading Group for Fourmulating a National Strategy on Intellectual Prop- CHINESE COMMUNIST erty Rights was established in January 2005. The Main National (ChiDir, p.159) PARTY The National Disaster-Reduction Commit- tee was established on 2 April 2005. (ChiDir, Leadership of the p.152) CCP CC General Secretary China National Machinery and Equip- Hu Jintao 02/11 PRC ment (Group) Corporation changed its name into China National Machinery In- dustry Corporation (SINOMACH), begin- POLITBURO Liu Jen-Kai ning 8 September 2005. -

PRC Official Activities Ple’S Construction Bank of China Since 1989

CHINA aktuell/Official Activities - 319/1 - Mai/May 1991 dustrial Bank of Japan Ltd., the Norin- chukin Bank, the Chiba Bank and the Kinki Bank, is to be the first tax-free Ioan from Japanese banks to the Peo PRC Official Activities ple’s Construction Bank of China since 1989. With a term of five years, the preferential commercial Ioan will be invested in key state projects in light industry, the textiles industry, and the machinery, electronics and raw materi als industries. (XNA, May 29,1991) AGREEMENTS WITH Nuclear Power Station. The agreement signed today is viewed as a further Mongolia (May 30) FOREIGN COUNTRIES development of Sino-French co-opera- Airline Cooperation minutes between tion in the field of nuclear energy. Civil Aviation Administration of China Wolfgang Bartke (XNA, May 28,1991) (CAAC) and its Mongolian counter- part. Under the minutes, China will Chile (May 23) Gabon (May 20) open, beginning from August, two Minutes of tue 12th meeting of the Agreement under which China will routes, Beijing - Ulan Bator, Huhhot - China-Chile Economic and Commer- provide a Ioan (no details). Ulan Bator, each two flights a week. cial Joint Committee. (XNA, May 20, 1991) The signing of the minutes marks the (XNA, May 24,1991) resumption of CAAC’s flights to Mon Gambia (May 09) golia after a lapse of 30 years. Mongo- Chile (May 31) Agreement under which China will lia reopened its airiine Service from Executive program for cultural ex- provide a Ioan (no details). Ulan Bator to Beijing in 1986 and now change in 1991-93. -

The Sixteenth Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party: Hu

THE SIXTEENTH CENTRAL COMMITTEE OF THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY Hu Gets What? Li Cheng and Lynn White Abstract This essay offers data about China’s Central Committee, Politburo, and Stand- ing Committee, e.g., turnover rates, generations, birthplaces, educations, oc- cupations, ethnicities, genders, experiences, and factions. Past statistics demonstrate trends over time. Norms of elite selection can be induced from such data, which allow a broad-based analysis of changes in China’s technoc- racy. New findings include evidence of cooperation among factions and swift promotions of province administrators. Did November of 2002 begin a new era of Chinese politics? Was the Sixteenth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) the first institutionalized transfer of power in the People’s Republic of China (PRC)? Younger leaders, the “fourth generation” headed by Hu Jintao, seemed to replace the old guard. Gerontocracy seemed moribund. Yet, this Li Cheng is the William R. Kenan Professor of Government, Hamilton College, Clinton, New York, U.S.A. Email: <[email protected]>. Lynn White is Professor at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, New Jersey, U.S.A. Email: <[email protected]>. For generous support, Li Cheng thanks the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the United States Institute of Peace, and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation. Lynn White thanks Hong Kong University’s Centre of Asian Studies and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation. The authors thank Sally Carman, Patrick Douglass, Joshua Eisenman, Ian Lawson, Li Yinsheng, Qi Li, Jennifer Schwartz, and Jennifer Young for their research assistance and an anonymous referee for suggesting ways to clarify the essay. -

China's Political Game Face Fendy Yang

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2012 China's Political Game Face Fendy Yang Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Yang, Fendy, "China's Political Game Face" (2012). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 775. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/775 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY University College International Affairs CHINA’S POLITICAL GAME FACE by Fendy Yang A thesis presented to University College of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 2012 Saint Louis, Missouri TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS .......................................................................................2 I. SOCIAL TRADITIONS ............................................................................................. 9 II: MILITARY PHILOSOPHIES ................................................................................. 19 III. NON-INTERVENTION ...................................................................................... -

What Is Labour?

PARADOXES OF LABOUR REFORM Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 in the 21st century. 'Worlds' signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within terri torial borders - some migrant communities overseas are also 'Chinese Worlds'. Other ethnic Chinese communities throughout the world have evolved new identities that transcend Chineseness in its established senses. They too are covered by this series. The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South-East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and his tory. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist mono graphs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social-science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Army Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Chinese Business in Malaysia Gregor Benton Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai Edmund Terence Gomez 1920-1927 Internal and International Steve Smith -

FIFI ANGGRAENI Cover 123.Pdf

DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PARTAI KOMUNIS CINA (PKC) DI BAWAH REZIM DENG XIAOPING PADA 1976-1989 SKRIPSI Diajukan guna melengkapi tugas akhir dan memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk menyelesaikan studi pada Jurusan Sejarah (S1) dan mencapai gelas Sarjana Sastra Oleh FIFI ANGGRAENI NIM. 110110301042 JURUSAN ILMU SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2015 i DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Fifi Anggraeni NIM : 110110301042 Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa karya ilmiah yang berjudul “Partai Komunis Cina (PKC) Di Bawah Rezim Deng Xiaoping Pada 1976-1989“ adalah benar-benar hasil karya sendiri, kecuali kutipan yang sudah saya sebutkan sumbernya, belum pernah diajukan pada institusi mana pun, dan bukan karya jiplakan. Saya bertanggung jawab atas keabsahan dan kebenaran isinya sesuai dengan sikap ilmiah yang harus dijunjung tinggi. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenarnya, tanpa ada tekanan dan paksaan dari pihak mana pun serta bersedia mendapat sanksi akademik jika ternyata di kemudian hari penyataan ini tidak benar. Jember 30 Oktober 2015 Yang menyatakan, Fifi Anggraeni NIM 110110301042 ii DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERSETUJUAN Skripsi ini telah disetujui untuk diujikan oleh: Dosen Pembimbing, Drs. Nurhadi Sasmita, M. Hum NIP. 196012151989021001 iii DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PENGESAHAN Diterima dan disahkan oleh Panitia Penguji Skripsi Program Strata 1 Jurusan Sejarah Fakultas Sastra Universitas Jember Pada hari : Jum’at Tanggal : 30 Oktober 2015 Ketua, Drs. Nurhadi Sasmita M. Hum NIP.196012151989021001 Anggota 1, Anggota 2, Drs. I.G. Krisnadi M. Hum Mrr. Ratna Endang W. SS., MA NIP. 19612151989021001 NIP. 196907271997022001 Mengesahkan Dekan Fakultas Sastra Universitas Jember Dr. Hairus Salikin, M. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9401311 A comparative study of provincial policy in China: The political economy of pollution control policy Maa, Shaw-Chang, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1993 UMI 300 N. -

Elite Conflict in the Post-Mao China

OccAsioNAl PApERs/ REpRiNTS SERiES 0 '• iN CoNTEMpoRARY ' AsiAN STudiEs NUMBER 7 - 1981 (44) ELITE CONFLICT IN THE 0 I 0 POST - MAO CHINA 0 Parris H. Chang 0 c:::;~· 0 General Editor: Hungdah Chiu Executive Editors: David Salem Lyushun Shen Managing Editor: Shirley Lay Editorial Advisory Board Professor Robert A. Scalapino, University of California at Berkeley Professor Martin Wilbur, Columbia University Professor Gaston J. Sigur, George Washington University Professor Shao-chuan Leng, University of Virginia Professor Lawrence W. Beer, University of Colorado Professor James Hsiung, New York University Dr. Robert Heuser, Max-Planck-Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law at Heidelberg Dr. Lih-wu Han, Political Science Association of the Republic of China Professor K. P. Misra, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Professor J. S. Prybyla, The Pennsylvania State University Professor Toshio Sawada, Sophia University, Japan Published with the cooperation of the Maryland International Law Society. All contributions (in English only) and communications should be sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu, University of Maryland School of Law, 500 West Baltimore Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 USA. All publications in this series reflect only the views of the authors. While the editor accepts responsibility for the selection of materials to be published, the individual author is responsible for statements of facts and expressions of opinion contained therein. Subscription is US $10.00 for 8 issues (regardless of the price of individual issues) in the United States and Canada and $12.00 for overseas. Check should be addressed to OPRSCAS and sent to Professor Hungdah Chiu. Price for single copy of this issue: US $2.00 ~1981 by Occasional Papers/Reprints Series in Contemporary Asian Studies, Inc.