Choosing a Secretary of State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Report ID

Number 21 April 2004 BAKER INSTITUTE REPORT NOTES FROM THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY BAKER INSTITUTE CELEBRATES ITS 10TH ANNIVERSARY Vice President Dick Cheney was man you only encounter a few the keynote speaker at the Baker times in life—what I call a ‘hun- See our special Institute’s 10th anniversary gala, dred-percenter’—a person of which drew nearly 800 guests to ability, judgment, and absolute gala feature with color a black-tie dinner October 17, integrity,” Cheney said in refer- 2003, that raised more than ence to Baker. photos on page 20. $3.2 million for the institute’s “This is a man who was chief programs. Cynthia Allshouse and of staff on day one of the Reagan Rice trustee J. D. Bucky Allshouse years and chief of staff 12 years ing a period of truly momentous co-chaired the anniversary cel- later on the last day of former change,” Cheney added, citing ebration. President Bush’s administra- the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cheney paid tribute to the tion,” Cheney said. “In between, Persian Gulf War, and a crisis in institute’s honorary chair, James he led the treasury department, Panama during Baker’s years at A. Baker, III, and then discussed oversaw two landslide victories in the Department of State. the war on terrorism. presidential politics, and served “There is a certain kind of as the 61st secretary of state dur- continued on page 24 NIGERIAN PRESIDENT REFLECTS ON CHALLENGES FACING HIS NATION President Olusegun Obasanjo of the Republic of Nigeria observed that Africa, as a whole, has been “unstable for too long” during a November 5, 2003, presentation at the Baker Institute. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

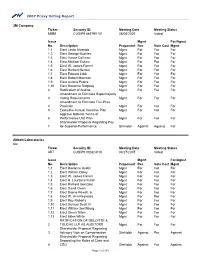

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making

Journal of Political Science Volume 33 Number 1 Article 2 November 2005 Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lasher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Lasher, Kevin J. (2005) "Madeleine Albright, Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 33 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol33/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Madeleine Albright , Gender, and Foreign Policy-Making Kevin J. Lashe r Francis Marion University Women are finally becoming major participants in the U.S. foreign policy-making establishment . I seek to un derstand how th e arrival of women foreign policy-makers might influence the outcome of U.S. foreign polic y by fo cusi ng 011 th e activities of Mad elei n e A !bright , the first wo man to hold the position of Secretary of State . I con clude that A !bright 's gender did hav e some modest im pact. Gender helped Albright gain her position , it affected the manner in which she carried out her duties , and it facilitated her working relationship with a Repub lican Congress. But A !bright 's gender seemed to have had relatively little effect on her ideology and policy recom mendations . ver the past few decades more and more women have won election to public office and obtained high-level Oappointive positions in government, and this trend is likely to continue well into the 21st century. -

James Knox Polk Collection, 1815-1949

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 POLK, JAMES KNOX (1795-1849) COLLECTION 1815-1949 Processed by: Harriet Chapell Owsley Archival Technical Services Accession Numbers: 12, 146, 527, 664, 966, 1112, 1113, 1140 Date Completed: April 21, 1964 Location: I-B-1, 6, 7 Microfilm Accession Number: 754 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION This collection of James Knox Polk (1795-1849) papers, member of Tennessee Senate, 1821-1823; member of Tennessee House of Representatives, 1823-1825; member of Congress, 1825-1839; Governor of Tennessee, 1839-1841; President of United States, 1844-1849, were obtained for the Manuscripts Section by Mr. and Mrs. John Trotwood Moore. Two items were given by Mr. Gilbert Govan, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and nine letters were transferred from the Governor’s Papers. The materials in this collection measure .42 cubic feet and consist of approximately 125 items. There are no restrictions on the materials. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the James Knox Polk Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research. SCOPE AND CONTENT The James Knox Polk Collection, composed of approximately 125 items and two volumes for the years 1832-1848, consist of correspondence, newspaper clippings, sketches, letter book indexes and a few miscellaneous items. Correspondence includes letters by James K. Polk to Dr. Isaac Thomas, March 14, 1832, to General William Moore, September 24, 1841, and typescripts of ten letters to Major John P. Heiss, 1844; letters by Sarah Polk, 1832 and 1891; Joanna Rucker, 1845- 1847; H. Biles to James K. Polk, 1833; William H. -

Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate

Order Code RL31607 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate October 16, 2002 name redacted, Meaghan Marshall, name redacted Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division name redacted Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: Differing Views in the Domestic Policy Debate Summary The debate over whether, when, and how to prosecute a major U.S. military intervention in Iraq and depose Saddam Hussein is complex, despite a general consensus in Washington that the world would be much better off if Hussein were not in power. Although most U.S. observers, for a variety of reasons, would prefer some degree of allied or U.N. support for military intervention in Iraq, some observers believe that the United States should act unilaterally even without such multilateral support. Some commentators argue for a stronger, more committed version of the current policy approach toward Iraq and leave war as a decision to reach later, only after exhausting additional means of dealing with Hussein’s regime. A number of key questions are raised in this debate, such as: 1) is war on Iraq linked to the war on terrorism and to the Arab-Israeli dispute; 2) what effect will a war against Iraq have on the war against terrorism; 3) are there unintended consequences of warfare, especially in this region of the world; 4) what is the long- term political and financial commitment likely to accompany regime change and possible democratization in this highly divided, ethnically diverse country; 5) what are the international consequences (e.g., to European allies, Russia, and the world community) of any U.S. -

World Bank Document

I~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Policy,Planning, and Research WORKING PAPERS Debtand International Finance InternationalEconomics Department The WorldBank August1989 Public Disclosure Authorized WPS 250 Public Disclosure Authorized The Baker Plan Progress,Shortcomings, and Future Public Disclosure Authorized William R. Cline The basic strategy spelled out in the Baker Plan (1985-88) remains valid, but stronger policy efforts are needed, banks should provide multiyear new money packages, exit bonds should be guaranteed to allow voluntary debt reduction by banks, and net capital flows to the highly indebted countries should be raised $15 billion a year. Successful emergence from the debt crisis, however, will depend primarily on sound eco- nomic policies in the debtor countries themselves. Public Disclosure Authorized The Policy, Planning. and Research Complex distributes PPR Working Papers to disseminate the findings of work in progress and to encourage the exchange of ideas among Bank staff and all others interested in development issues. T'hese papers carry the names of the authors, reflect only their views, and should be used and cited accordingly. The findings, interpiciations. and conclusions are the authors' own. They should not be attnbuted to the World Bank, its Board of Directors, its management, or any of its mernber countries. |Policy, Planning,and Roenorch | The. Baker Plan essentially made existing multilateral development banks raised net flows strategy cn the debt problem more concrete. by only one-tenth of the targeted $3 billion Like existing policy, it iejected a bankruptcy annually. If the IMF and bilateral export credit approach to the problem, judging that coerceo agencies are included, net capital flows from forgiveness would "admit defeat" and cut official sources to the highly indebted countries borrowers off from capital markets for many (HICs) actually fell, from $9 annually in 1983- years to come. -

Hearings on the Nomination of Hon. Rich- Ard C. Holbrooke to Serve As Us Ambas

S. HRG. 106±225 HEARINGS ON THE NOMINATION OF HON. RICH- ARD C. HOLBROOKE TO SERVE AS U.S. AMBAS- SADOR TO THE UNITED NATIONS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 17, 22, AND 24, 1999 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 57±735 CC WASHINGTON : 1999 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming BARBARA BOXER, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey BILL FRIST, Tennessee STEPHEN E. BIEGUN, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director (II) CONTENTS THURSDAY, JUNE 17, 1999 Page Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 4 Boxer, Barbara, U.S. Senator from California, prepared statement of ............... 34 Helms, Jesse, U.S. Senator from North Carolina, opening statement ................ 1 Holbrooke, Hon. Richard C., nominee to be U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations .................................................................................................................. 10 Prepared statement of ...................................................................................... 16 Moynihan, Daniel Patrick, U.S. Senator from New York, statement ................. 9 Warner, John W., U.S. Senator from Virginia, statement ................................... 7 TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 1999 Biden, Joseph R., Jr., U.S. Senator from Delaware, opening statement ............ 47 Helms, Jesse, U.S. -

JAMES A. BAKER, III the Case for Pragmatic Idealism Is Based on an Optimis- Tic View of Man, Tempered by Our Knowledge of Human Imperfection

Extract from Raising the Bar: The Crucial Role of the Lawyer in Society, by Talmage Boston. © State Bar of Texas 2012. Available to order at texasbarbooks.net. TWO MOST IMPORTANT LAWYERS OF THE LAST FIFTY YEARS 67 concluded his Watergate memoirs, The Right and the Power, with these words that summarize his ultimate triumph in “raising the bar”: From Watergate we learned what generations before us have known: our Constitution works. And during the Watergate years it was interpreted again so as to reaffirm that no one—absolutely no one—is above the law.29 JAMES A. BAKER, III The case for pragmatic idealism is based on an optimis- tic view of man, tempered by our knowledge of human imperfection. It promises no easy answers or quick fixes. But I am convinced that it offers our surest guide and best hope for navigating our great country safely through this precarious period of opportunity and risk in world affairs.30 In their historic careers, Leon Jaworski and James A. Baker, III, ended up in the same place—the highest level of achievement in their respective fields as lawyers—though they didn’t start from the same place. Leonidas Jaworski entered the world in 1905 as the son of Joseph Jaworski, a German-speaking Polish immigrant, who went through Ellis Island two years before Leon’s birth and made a modest living as an evangelical pastor leading small churches in Central Texas towns. James A. Baker, III, entered the world in 1930 as the son, grand- son, and great-grandson of distinguished lawyers all named James A. -

Transcript by Rev.Com Page 1 of 13 Former U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker, III, Whose 30-Year Legacy of Public Service In

Former U.S. Secretary of State James A. Baker, III, whose 30-year legacy of public service includes senior positions under three U.S. presidents, was interviewed at the 2020 Starr Federalist Lecture at Baylor Law on Monday, October 13 at noon CDT. Secretary Baker was interviewed by accomplished author and distinguished trial lawyer Talmage Boston, as they discussed Secretary Baker’s remarkable career, the leadership lessons learned from his years of experience in public service, and the skills and capabilities of lawyers that contribute to success as effective leaders and problem-solvers. Baker and Boston also discussed Baker’s newly released biography, The Man Who Ran Washington: The Life and Times of James A. Baker III, by Peter Baker and Susan Glasser. The Wall Street Journal calls The Man Who Ran Washington “an illuminating biographical portrait of Mr. Baker, one that describes the arc of his career and, along the way, tells us something about how executive power is wielded in the nation’s capital.” In Talmage Boston’s review of The Man Who Ran Washington, published in the Washington Independent Review of Books, Boston states, “[This] book provides a complete, persuasive explanation of how this 45-year-old prominent but politically inexperienced Houston transactional lawyer arrived in the nation’s capital as undersecretary of commerce in July 1975, and within six months, began his meteoric rise to the peak of the DC power pyramid…” The New York Times calls it “enthralling,” and states that, “The former Secretary of State’s experiences as a public servant offer timeless lessons in how to use personal relationships, broad-based coalitions and tireless negotiating to advance United States interests.” The Federalist Papers are a collection of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay between 1787 and 1788. -

Growth of Presidential Power

Growth of Presidential Power A. Article II of the Constitution 1. Article II is the part of the Constitution that deals with the Executive Branch. 2. Article II is basically just a short outline of powers. 3. A large part of America’s early political history deals with defining the extent of the executive power. B. The Changing View of Presidential Power 1. Why Presidential Power Has Grown -The presidency is in the hands of one person, rather than many, and many Presidents have worked to expand the powers of their office. -As the country grew and industrialized, especially in times of emergency, people demanded that the Federal Government play a larger role and looked to the President for leadership. -Congress has delegated much authority to the President, although presidential control over foreign affairs is greater than it is over domestic affairs. Congress simply continues to assert itself in the implementation of social programs. -Presidents have the attention and general respect of the media, the public, and their own party. C. How Presidents Have Viewed Their Power 1. Stronger and more effective Presidents have taken a broad view of the powers of the office. 2. Teddy Roosevelt viewed his broad use of Presidential powers as the “Stewardship Theory”, which means that the President should have the power to act as a “steward” over the country. 3. Recent, very strong presidents have given rise to the phrase “Imperial Presidency”, which implies that the President becomes as strong as an emperor. The term is often used to refer to the administration of Richard Nixon.