The Lady of the House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norfolk Through a Lens

NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service 2 NORFOLK THROUGH A LENS A guide to the Photographic Collections held by Norfolk Library & Information Service History and Background The systematic collecting of photographs of Norfolk really began in 1913 when the Norfolk Photographic Survey was formed, although there are many images in the collection which date from shortly after the invention of photography (during the 1840s) and a great deal which are late Victorian. In less than one year over a thousand photographs were deposited in Norwich Library and by the mid- 1990s the collection had expanded to 30,000 prints and a similar number of negatives. The devastating Norwich library fire of 1994 destroyed around 15,000 Norwich prints, some of which were early images. Fortunately, many of the most important images were copied before the fire and those copies have since been purchased and returned to the library holdings. In 1999 a very successful public appeal was launched to replace parts of the lost archive and expand the collection. Today the collection (which was based upon the survey) contains a huge variety of material from amateur and informal work to commercial pictures. This includes newspaper reportage, portraiture, building and landscape surveys, tourism and advertising. There is work by the pioneers of photography in the region; there are collections by talented and dedicated amateurs as well as professional art photographers and early female practitioners such as Olive Edis, Viola Grimes and Edith Flowerdew. More recent images of Norfolk life are now beginning to filter in, such as a village survey of Ashwellthorpe by Richard Tilbrook from 1977, groups of Norwich punks and Norfolk fairs from the 1980s by Paul Harley and re-development images post 1990s. -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

The Settlement of East and West Flegg in Norfolk from the 5Th to 11Th Centuries

TITLE OF THESIS The settlement of East and West Flegg in Norfolk from the 5th to 11th centuries By [Simon Wilson] Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted For the Degree of Masters of Philosophy Year 2018 ABSTRACT The thesis explores the –by and English place names on Flegg and considers four key themes. The first examines the potential ethnicity of the –bys and concludes the names carried a distinct Norse linguistic origin. Moreover, it is acknowledged that they emerged within an environment where a significant Scandinavian population was present. It is also proposed that the cluster of –by names, which incorporated personal name specifics, most likely emerged following a planned colonisation of the area, which resulted in the takeover of existing English settlements. The second theme explores the origins of the –by and English settlements and concludes that they derived from the operations of a Middle Saxon productive site of Caister. The complex tenurial patterns found between the various settlements suggest that the area was a self sufficient economic entity. Moreover, it is argued that royal and ecclesiastical centres most likely played a limited role in the establishment of these settlements. The third element of the thesis considers the archaeological evidence at the –by and English settlements and concludes that a degree of cultural assimilation occurred. However, the presence of specific Scandinavian metal work finds suggests that a distinct Scandinavian culture may have survived on Flegg. The final theme considers the economic information recorded within the folios of Little Domesday Book. It is argued that both the –by and English communities enjoyed equal economic status on the island and operated a diverse economy. -

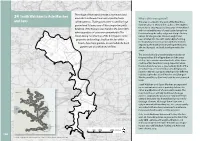

24 South Walsham to Acle Marshes and Fens

South Walsham to Acle Marshes The village of Acle stands beside a vast marshland 24 area which in Roman times was a great estuary Why is this area special? and Fens called Gariensis. Trading ports were located on high This area is located to the west of the River Bure ground and Acle was one of those important ports. from Moulton St Mary in the south to Fleet Dyke in Evidence of the Romans was found in the late 1980's the north. It encompasses a large area of marshland with considerable areas of peat located away from when quantities of coins were unearthed in The the river along the valley edge and along tributary Street during construction of the A47 bypass. Some valleys. At a larger scale, this area might have properties in the village, built on the line of the been divided into two with Upton Dyke forming beach, have front gardens of sand while the back the boundary between an area with few modern impacts to the north and a more fragmented area gardens are on a thick bed of flints. affected by roads and built development to the south. The area is basically a transitional zone between the peat valley of the Upper Bure and the areas of silty clay estuarine marshland soils of the lower reaches of the Bure these being deposited when the marshland area was a great estuary. Both of the areas have nature conservation area designations based on the two soil types which provide different habitats. Upton Broad and Marshes and Damgate Marshes and Decoy Carr have both been designated SSSIs. -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

Regulation 25 Consultation

Regulation 25 Consultation Technical & Public Consultation Summary August 2009 Greater Norwich Development Partnership Regulation 25 Consultation 233902 BNI NOR 1 A PIMS 233902BN01/Report 14 August 2009 Technical & Public Consultation Summary August 2009 Greater Norwich Development Partnership Regulation 25 Consultation Issue and revision record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A 03.08.09 Needee Myers Draft Report B 15.08.09 Needee Myers Emma Taylor Eddie Tyrer Final Report This document has been prepared for the titled project or Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for this named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used document to any party other than the person by whom it was for any other project without an independent check being commissioned. carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Mott MacDonald being obtained. Mott MacDonald accepts no To the extent that this report is based on information supplied responsibility or liability for the consequence of this document by other parties, Mott MacDonald accepts no liability for any being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it loss or damage suffered by the client, whether contractual or was commissioned. Any person using or relying on the tortious, stemming from any conclusions based on data document for such other purpose agrees, and will by such supplied by parties other than Mott MacDonald and used by use or reliance be taken to confirm his agreement to indemnify Mott MacDonald in preparing this report. Mott MacDonald for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Regulation 25 Consultation Content Chapter Title Page 1. -

Wickham Court and the Heydons Gregory

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society glrcirecoingia Iantinna WICKHAM COURT AND THE HEYDONS By MOTHER MARY GREGORY, L.M., M.A.OxoN. Lecturer in History, Coloma Training College, Wickham Court THE manor of West Wickham in Kent came into the hands of the Heydon family of Baconsthorpe, Norfolk, in the latter years of the fifteenth century. The Heydons, a family which could be classed among the lesser gentry in the earlier part of the century, were in the ascendant in the social scale. The accumulation of manors was a sign of prosperity, and many hitherto obscure families were climbing into prominence by converting the wealth they had obtained through lucrative legal posts into real estate. The story of the purchase of West Wickham by the Heydons and of its sale by them just over a century later provides a useful example of the varying fortunes of a family of the gentry at this date, for less is known about the gentry as a class than of the nobility. John Heydon had prospered as a private lawyer, and his son Henry was the first of the family to be knighted. Henry's father made a good match for him, marrying him into the house of Boleyn, or Bullen, a family which was advancing even more rapidly to prominence. The lady chosen was a daughter of Sir Geoffrey Boleyn, a wealthy mercer who, in 1457, was elected Lord Mayor of London. Sir Geoffrey's grandson married Elizabeth Howard, a daughter of the Duke of Norfolk; his great-granddaughter, Henry Heydon's great-niece, was to be queen of England. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 54S1 (2019): 287–314 Doi: 10.2478/Stap-2019-0014

Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 54s1 (2019): 287–314 doi: 10.2478/stap-2019-0014 TRACING PATTERNS OF INTRA-SPEAKER VARIATION IN EARLY ENGLISH CORRESPONDENCE: A CHANGE FROM ABOVE IN THE PASTON LETTERS* JUAN M. HERNÁNDEZ-CAMPOY, J. CAMILO CONDE-SILVESTRE AND TAMARA GARCÍA-VIDAL1 ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to explore the impact of social and context factors on the diffusion of a linguistic change from above, namely the deployment of the spelling innovation <th> in fifteenth- century English, and especially in some letters from the well-known Paston collection of correspondence. We particularly focus on the socio-stylistic route of this change from above, observing the sociolinguistic behaviour of some letter writers (members of the Paston family) in connection with the social-professional status of their recipients, the interpersonal relationship with them, as well as the contexts and styles of the letters. In this way, different dimensions of this change from above in progress in fifteenth-century English can be reconstructed. Keywords: Historical sociolinguistics; sociolinguistic styles; change from above; history of English spelling; late Middle English; Paston Letters. 1. Theoretical background After three decades of continuous research, historical sociolinguistics is now a well-established discipline with a methodology that has allowed researchers to trace new dimensions of historically attested changes along the social and linguistic dimensions, as well as to test some widely-accepted sociolinguistic tenets or ‘universals’: the curvilinear hypothesis, overt-covert prestige patterns, * Financial support for this research has been crucially provided by the DGICT of the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (FFI2014-56084-P) and by Fundación Séneca, the Murcian Agency for Science and Technology (19331-PHCS-14 and 20585-EE-18). -

I1 ENGLISH RURAL LIFE in the FIFTEENTH CENTURY ISTORY Sometimes Has Scattered Poppy Without Merit

I1 ENGLISH RURAL LIFE IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY ISTORY sometimes has scattered poppy without merit. H We know little of many who were once great in the earth, and still less of the life of the people in their times. The life of the past must be visualized by piecing together detached and scattered fragments from many sources. The result is a composite picture, not a portrait. It is only now and then that the student of history is able to penetrate be- hind the veil of obscurity and get glimpses of intimate per- sonal life and learn to know the men and women of the past with some degree of acquaintance. A rare opportunity to know English provincial life in the fifteenth century is afforded in that wonderful collection known as “The Paston Letters.” This familiar correspond- ence of a Norfolk family, whose position was that of small gentry, covers three generations in some of the most stirring years of English history. It was the age when England’s empire in France was wrested from her by Joan of Arc; the age when the white rose of York and the red rose of Lan- caster were dyed a common color on the battlefields of Barnet, Towton, Wakefield Heath, and Bosworth Field. It was the century of W’arwick the kingmaker, and Henry Tudor ; of Sir Thomas More’s birth and of Caxton’s “Game of Chess.” The intense human interest of these letters has command- ed the admiration of readers ever since John Fenn edited 116 Rural Life in XV Century England 117 them, or those then known, in 1787. -

Abstract the Paston Women and Gentry Culture: The

ABSTRACT THE PASTON WOMEN AND GENTRY CULTURE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIAL IDENTITY IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND This gender and social history examines the role of the Paston family in the developing gentry culture in fifteenth-century England. A family who desired to increase their social standing, the Pastons worked to first obtain land and wealth in order to become a part of the gentry. This study primarily examines the second way that the Pastons proved their gentility; through exhibiting behavior associated with the gentry, the Pastons proved to the public that they were above the peasantry and that they belonged in the upper echelons of society. In their quest for gentility, the behavior of the Paston women was particularly important to the efforts of their family. This thesis focuses on the ways that Agnes and Margaret Paston adopted the advice present in contemporary conduct manuals and how they incorporated such behavior into their letters. By presenting an image of gentility in their letters, Agnes and Margaret participated in both the developing gentry culture in fifteenth-century England and in their family’s efforts to increase their social status. Letter writing was a venue through which medieval women could express their opinions, and in the case of the Paston women, it was a way for them to directly impact the station of their family. The exercise of gentility in which the Paston women participated demonstrates one way the creation of an individual identity impacts both social status and group formation in -

Articulations of Masculinity in the Paston Correspondence

"He Ys A Swyre of WorchypM: Articulations of Masculinity In The Paston Correspondence by Andrew C. Hall A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research through the Department of History in Partial Fulfilrnent of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 1997 copyright 1997 Andrew C. Hall National Library BiiTnationale du Cana Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Se ~ices senrices bibliographiques 395 WMiStreet 395. nie Wellington Oltawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaûN K1AONQ Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in bis thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract This thesis examines the gendered experience of the fifteenth-century provincial gentleman through the letters of the Paston farrdly. On the whole, the men of the gentry did not consciously ponder their identities as men. However, in their articulations of daily social concerns, these men often engaged in discussions about masculinity and male sexuality.