University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard II First Folio

FIRST FOLIO Teacher Curriculum Guide Welcome to the Table of Contents Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production Page Number of About the Play Richard II Synopsis of Richard II…..…….….... …….….2 by William Shakespeare Interview with the Director/About the Play…3 Historical Context: Setting the Stage….....4-5 Dear Teachers, Divine Right of Kings…………………..……..6 Consistent with the STC's central mission to Classroom Connections be the leading force in producing and Tackling the Text……………………………...7 preserving the highest quality classic theatre , Before/After the Performance…………..…...8 the Education Department challenges Resource List………………………………….9 learners of all ages to explore the ideas, Etiquette Guide for Students……………….10 emotions and principles contained in classic texts and to discover the connection between The First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide for classic theatre and our modern perceptions. Richard II was developed by the We hope that this First Folio Teacher Shakespeare Theatre Company Education Curriculum Guide will prove useful as you Department. prepare to bring your students to the theatre! ON SHAKESPEARE First Folio Guides provide information and For articles and information about activities to help students form a personal Shakespeare’s life and world, connection to the play before attending the please visit our website production. First Folio Guides contain ShakespeareTheatre.org, material about the playwrights, their world to download the file and their works. Also included are On Shakespeare. approaches to explore the plays and productions in the classroom before and after the performance. Next Steps If you would like more information on how First Folio Guides are designed as a you can participate in other Shakespeare resource both for teachers and students. -

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Actes Des Congrès De La Société Française Shakespeare

Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare 36 | 2018 Shakespeare et la peur From fear to anxiety in Shakespeare’s Macbeth Christine Sukic Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/4141 DOI : 10.4000/shakespeare.4141 ISSN : 2271-6424 Éditeur Société Française Shakespeare Référence électronique Christine Sukic, « From fear to anxiety in Shakespeare’s Macbeth », Actes des congrès de la Société française Shakespeare [En ligne], 36 | 2018, mis en ligne le 07 octobre 2019, consulté le 25 août 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/shakespeare/4141 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/shakespeare. 4141 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 25 août 2021. © SFS From fear to anxiety in Shakespeare’s Macbeth 1 From fear to anxiety in Shakespeare’s Macbeth Christine Sukic 1 In the early modern period, fear was either a necessary passion, as when Christians are said to live in the “fear of God”1, or an emotion that had to be suppressed or at least mitigated, when it concerned the “fear of death”. There are numerous books of ars moriendi that claim, in their titles, that they intend to “take away the feare of death”2 or will “comfort” Christians against that fear3. In a Christian context, fear was thus seen as a sort of natural passion, which was acceptable as long as it was “holy fear”, as Emilia calls it in Two Noble Kinsmen (5.1.149), but that had to be alleviated in order for Christians to “die well”, with as little fear as possible. In Measure for Measure, Claudio seems to have learned to “encounter darkness as a bride / And hug it in [his] arms” (3.1.83-4) until Isabella’s visit reminds him that “Death is a fearful thing” (3.1.115). -

Final Thesis.Pdf

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Kersey, H. (2017) Aristocratic female inheritance and property holding in thirteenth-century England. Ph.D. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] ARISTOCRATIC FEMALE INHERITANCE AND PROPERTY HOLDING IN THIRTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND By Harriet Lily Kersey Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 ii Abstract This thesis explores aristocratic female inheritance and property holding in the thirteenth century, a relatively neglected topic within existing scholarship. Using the heiresses of the earldoms and honours of Chester, Pembroke, Leicester and Winchester as case studies, this thesis sheds light on the processes of female inheritance and the effects of coparceny in a turbulent period of English history. The lives of the heiresses featured in this thesis span the reigns of three English kings: John, Henry III and Edward I. The reigns of John and Henry saw bitter civil wars, whilst Edward’s was plagued with expensive foreign wars. -

I 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': a NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF

'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 i 'A MAN MOSTE MEETE': A NATIONWIDE SURVEY OF JUSTICES OF THE PEACE IN MID-TUDOR ENGLAND, 1547-1582 _____________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _____________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________ By Clarissa Elisabeth Hinojosa May 2014 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a national study of English justices of the peace (JPs) in the mid- Tudor era. It incorporates comparable data from the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and the Elizabeth I. Much of the analysis is quantitative in nature: chapters compare the appointments of justices of the peace during the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I, and reveal that purges of the commissions of the peace were far more common than is generally believed. Furthermore, purges appear to have been religiously- based, especially during the reign of Elizabeth I. There is a gap in the quantitative data beginning in 1569, only eleven years into Elizabeth I’s reign, which continues until 1584. In an effort to compensate for the loss of quantitative data, this dissertation analyzes a different primary source, William Lambarde’s guidebook for JPs, Eirenarcha. The fourth chapter makes particular use of Eirenarcha, exploring required duties both in and out of session, what technical and personal qualities were expected of JPs, and how well they lived up to them. -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Richard Kilburne, a Topographie Or Survey of The

Richard Kilburne A topographie or survey of the county of Kent London 1659 <frontispiece> <i> <sig A> A TOPOGRAPHIE, OR SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. With some Chronological, Histori= call, and other matters touching the same: And the several Parishes and Places therein. By Richard Kilburne of Hawk= herst, Esquire. Nascimur partim Patriæ. LONDON, Printed by Thomas Mabb for Henry Atkinson, and are to be sold at his Shop at Staple-Inn-gate in Holborne, 1659. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO THE NOBILITY, GEN= TRY and COMMONALTY OF KENT. Right Honourable, &c. You are now presented with my larger Survey of Kent (pro= mised in my Epistle to my late brief Survey of the same) wherein (among severall things) (I hope conducible to the service of that Coun= ty, you will finde mention of some memorable acts done, and offices of emi= <iv> nent trust borne, by severall of your Ancestors, other remarkeable matters touching them, and the Places of Habitation, and Interment of ma= ny of them. For the ready finding whereof, I have added an Alphabeticall Table at the end of this Tract. My Obligation of Gratitude to that County (wherein I have had a comfortable sub= sistence for above Thirty five years last past, and for some of them had the Honour to serve the same) pressed me to this Taske (which be= ing finished) If it (in any sort) prove servicea= ble thereunto, I have what I aimed at; My humble request is; That if herein any thing be found (either by omission or alteration) substantially or otherwise different from my a= foresaid former Survey, you would be pleased to be informed, that the same happened by reason of further or better information (tend= ing to more certaine truths) than formerly I had. -

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399

York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 Edited by David M. Smith 2020 www.york.ac.uk/borthwick archbishopsregisters.york.ac.uk Online images of the Archbishops’ Registers cited in this edition can be found on the York’s Archbishops’ Registers Revealed website. The conservation, imaging and technical development work behind the digitisation project was delivered thanks to funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Register of Alexander Neville 1374-1388 Register of Thomas Arundel 1388-1396 Sede Vacante Register 1397 Register of Robert Waldby 1397 Sede Vacante Register 1398 Register of Richard Scrope 1398-1405 YORK CLERGY ORDINATIONS 1374-1399 Edited by DAVID M. SMITH 2020 CONTENTS Introduction v Ordinations held 1374-1399 vii Editorial notes xiv Abbreviations xvi York Clergy Ordinations 1374-1399 1 Index of Ordinands 169 Index of Religious 249 Index of Titles 259 Index of Places 275 INTRODUCTION This fifth volume of medieval clerical ordinations at York covers the years 1374 to 1399, spanning the archiepiscopates of Alexander Neville, Thomas Arundel, Robert Waldby and the earlier years of Richard Scrope, and also including sede vacante ordinations lists for 1397 and 1398, each of which latter survive in duplicate copies. There have, not unexpectedly, been considerable archival losses too, as some later vacancy inventories at York make clear: the Durham sede vacante register of Alexander Neville (1381) and accompanying visitation records; the York sede vacante register after Neville’s own translation in 1388; the register of Thomas Arundel (only the register of his vicars-general survives today), and the register of Robert Waldby (likewise only his vicar-general’s register is now extant) have all long disappeared.1 Some of these would also have included records of ordinations, now missing from the chronological sequence. -

Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England

ABSTRACT “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided by Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England Laura Christine Oliver, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D. This thesis argues that while patriarchy was certainly present in England during the late medieval period, women of the middle and upper classes were able to exercise agency to a certain degree through using both the patriarchal bargain and an economy of makeshifts. While the methods used by women differed due to the resources available to them, the agency afforded women by the patriarchal bargain and economy of makeshifts was not limited to the aristocracy. Using Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe as cases studies, this thesis examines how these women exercised at least a limited form of agency. Additionally, this thesis examines whether ordinary women have access to the same agency as elite women. Although both were exceptional women during this period, they still serve as ideal case studies because of the sources available about them and their status as role models among their contemporaries. “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided By Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England by Laura Christine Oliver, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Julie A. -

Aclou Condé-Sur-Risle Malleville-Sur-Le-Bec Aizier

Communes du ressort du tribunal d'instance de BERNAY Aclou Condé-sur-Risle Malleville-sur-le-Bec Aizier Conteville Malouy Appeville-Annebault Cormeilles Manneville-la-Raoult Asnières Corneville-la-Fouquetière Manneville-sur-Risle Authou Corneville-sur-Risle Marais-Vernier Bailleul-la-Vallée Courbépine Martainville Barc Drucourt Mélicourt Barneville-sur-Seine Duranville Menneval Barquet Écaquelon Mesnil-en-Ouche Barville Écardenville-la-Campagne Mesnil-Rousset Bazoques Épaignes Montfort-sur-Risle Beaumontel Épreville-en-Lieuvin Montreuil-l'Argillé Beaumont-le-Roger Étréville Monts du Roumois Bec-Hellouin Éturqueraye Morainville-Jouveaux Bernay Fatouville-Grestain Morsan Berthouville Favril Nassandres sur Risle Berville-la-Campagne Ferrières-Saint-Hilaire Neuville-du-Bosc Berville-sur-Mer Fiquefleur-Équainville Neuville-sur-Authou Beuzeville Flancourt-Crescy-en-Roumois Noards Bois-Hellain Folleville Noë-Poulain Boisney Fontaine-l'Abbé Notre-Dame-d'Épine Boissey-le-Châtel Fontaine-la-Louvet Notre-Dame-du-Hamel Boissy-Lamberville Fort-Moville Noyer-en-Ouche Bonneville-Aptot Foulbec Piencourt Bosgouet Fourmetot Places Bosrobert Franqueville Plainville Bosroumois Freneuse-sur-Risle Planquay Boulleville Fresne-Cauverville Plasnes Bouquelon Giverville Plessis-Sainte-Opportune Bouquetot Glos-sur-Risle Pont-Audemer Bourg-Achard Goulafrière Pont-Authou Bournainville-Faverolles Goupillières Poterie-Mathieu Bourneville-Sainte-Croix Grand Bourgtheroulde Préaux Bray Grand-Camp Quillebeuf-sur-Seine Brestot Grosley-sur-Risle Romilly-la-Puthenaye Brétigny -

Hambleton 5/10/07 17:42 Page 1

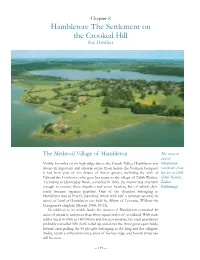

Hambleton 5/10/07 17:42 Page 1 Chapter 8 Hambleton: The Settlement on the Crooked Hill Sue Howlett The Medieval Village of Hambleton The western end of Visible for miles on its high ridge above the Gwash Valley, Hambleton was Hambleton always an important and valuable estate. Even before the Norman Conquest peninsula from it had been part of the dower of Saxon queens, including the wife of the air in 2006 Edward the Confessor, who gave her name to the village of Edith Weston. (John Nowell, According to Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, the manor was extensive Zodiac enough to contain three churches and seven hamlets, five of which after- Publishing) wards became separate parishes. One of the churches belonging to Hambleton was St Peter’s, Stamford, which with half a carucate (around 60 acres) of land at Hambleton was held by Albert of Lorraine, William the Conquerer’s chaplain (Morris 1980, 19-21). In addition to its arable lands, the manor of Hambleton contained 40 acres of meadow and more than three square miles of woodland. With male adults listed in 1086 as 140 villeins and thirteen bordars, the total population probably exceeded 500. Serfs toiled up and down the three great open fields, behind oxen pulling the 45 ploughs belonging to the king and the villagers. Today, nearly a millennium later, areas of former ridge and furrow strips can still be seen. – 149 – Hambleton 5/10/07 17:43 Page 2 An 1839 drawing of Hambleton Church (Uppingham School Archives) Some time after the Domesday survey, William the Conquerer granted Hambleton to the powerful Norman family of Umfraville, who sub-divided the large and sprawling manor into two: Great and Little Hambleton. -

GIPE-001848-Contents.Pdf

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Library III~III~~ mlll~~ I~IIIIIIII~IIIU GlPE-PUNE-OO 1848 CONSTITUTION AL HISTORY OF ENGLAND STUBBS 1Lonbon HENRY FROWDE OXFORD tTNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE AMEN CORNEl!. THE CONSTITUTIONAL mSTORY OF ENGLAND IN ITS ORIGIN AND DEtrLOP~'r BY WILLIAM STUBBS, D.D., BON. LL.D. BISHOP OF CHESTER VOL. III THIRD EDITIOlY @d.orlt AT Tag CLARENDON PRESS J( Deco LXXXIV [ A II rig"'" reserved. ] V'S;LM3 r~ 7. 3 /fyfS CONTENTS. CHAPTER XVIII. LANCASTER AND YORK. 299. Character of the period, p. 3. 300. Plan of the chapter, p. 5. 301. The Revolution of 1399, p. 6. 302. Formal recognition of the new Dynasty, p. 10. 303. Parliament of 1399, p. 15. 304. Conspiracy of the Earls, p. 26. 805. Beginning af difficulties, p. 37. 306. Parliament of 1401, p. 29. 807. Financial and poli tical difficulties, p. 35. 308. Parliament of 1402, 'p. 37. 309. Rebellion of Hotspur, p. 39. 310. Parliament of 14°40 P.42. 311. The Unlearned Parliament, P.47. 312. Rebellion of Northum berland, p. 49. 813. The Long Parliament of 1406, p. 54. 314. Parties fonned at Court, p. 59. 315. Parliament at Gloucester, 14°7, p. 61. 816. Arundel's administration, p. 63. 317. Parlia mont of 1410, p. 65. 318. Administration of Thomae Beaufort, p. 67. 319. Parliament of 14II, p. 68. 820. Death of Henry IV, p. 71. 821. Character of H'!I'l'Y. V, p. 74. 322. Change of ministers, p. 78. 823. Parliament of 1413, p. 79. 324. Sir John Oldcastle, p. 80. 325.