Fragile Traces, Treacherous Sands: Ronen Sharabani and Micha Ullman's Intergenerational Encounter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Semitism: a History

ANTI-SEMITISM: A HISTORY 1 www.counterextremism.com | @FightExtremism ANTI-SEMITISM: A HISTORY Key Points Historic anti-Semitism has primarily been a response to exaggerated fears of Jewish power and influence manipulating key events. Anti-Semitic passages and decrees in early Christianity and Islam informed centuries of Jewish persecution. Historic professional, societal, and political restrictions on Jews helped give rise to some of the most enduring conspiracies about Jewish influence. 2 Table of Contents Religion and Anti-Semitism .................................................................................................... 5 The Origins and Inspirations of Christian Anti-Semitism ................................................. 6 The Origins and Inspirations of Islamic Anti-Semitism .................................................. 11 Anti-Semitism Throughout History ...................................................................................... 17 First Century through Eleventh Century: Rome and the Rise of Christianity ................. 18 Sixth Century through Eighth Century: The Khazars and the Birth of an Enduring Conspiracy Theory AttacKing Jewish Identity ................................................................. 19 Tenth Century through Twelfth Century: Continued Conquests and the Crusades ...... 20 Twelfth Century: Proliferation of the Blood Libel, Increasing Restrictions, the Talmud on Trial .............................................................................................................................. -

Americans and the Holocaust Teacher Guide Interpreting News of World Events 1933–1938

AMERICANS AND THE HOLOCAUST TEACHER GUIDE INTERPRETING NEWS OF WORLD EVENTS 1933–1938 ushmm.org/americans AMERICANS AND THE HOLOCAUST INTERPRETING NEWS OF WORLD EVENTS 1933–1938 OVERVIEW By examining news coverage around three key events related to the early warning signs of the Holocaust, students will learn that information about the Nazi persecution of European Jews was available to the public. They will also consider the question of what other issues or events were competing for Americans’ attention and concern at the same time. Despite the many issues that were on their minds during the period 1933–1938, some Americans took actions to help persecuted Jews abroad, with varying degrees of effectiveness. This lesson explores the following questions: n How did Americans learn about the Nazi persecution of Jews in Europe in the context of other international, national, and local news stories? How did they make sense of these events? HISTORY KEY QUESTIONS EXPLORED 1. What information about the Nazi persecution of Jews was being reported in the news media throughout the United States? 2. What else was being covered in the news and competing for the public’s attention during this period? 3. How did Americans respond to this knowledge? What impact did these actions have? 4. How might competing issues have influenced the willingness of the American public to respond to the early persecution of Jews in Europe? HISTORY LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Students will learn that information about the persecution of European Jews was available in newspapers throughout the United States. 2. Students will understand that competing concerns influenced the willingness of the American people to respond to this persecution. -

Being a Yekke Is a Really Big Deal for My Mum! on the Intergenerational Transmission of Germanness Amongst German Jews in Israel

Austausch, Vol. 2, Issue 1, July 2013 Being a Yekke is a really big deal for my mum! On the intergenerational transmission of Germanness amongst German Jews in Israel Dani Kranz (University of Erfurt, [email protected]) Throughout history, Germans1 have left German territory2 for different destinations worldwide, including: Eastern Europe; the United States; Australia, Africa and South America. Germans now constitute a global diaspora (cf. Schulze et. al. 2008). The vast majority of emigrants left German territory to seek a better life abroad. The new destinations attracted German emigrants with a mix of push and pull factors, with pull factors dominating. In the case of German emigrants there are sources depicting the maintenance and the transmission of Germanness, yet one group remains under-researched in this respect. This group is that of the German Jews.3 This article offers an in-depth, cross-generational case study of the transmission of Germanness of these ‘other Germans’ in the British mandate of Palestine and later Israel. While many German Jews left for the same destinations as other – non-Jewish - German emigrants, only a small number emigrated to the British mandate of Palestine (Rosenstock 1956, Stone 1997, Wormann 1970). By and large the vast bulk of all Jews from Germany fled to the British mandate as an effect of Nazi terror. Unlike previous waves of emigration, this move was forced upon them. It caused trauma (Viest 1977: 56) because it was determined by push factors, not by pull factors. This means that the vast majority of all German Jews who came to the British mandate of Palestine were refugees (Gelber & Goldstern 1988; Sela-Sheffy 2006, 2011; Viest 1977). -

Refugees and Relief: the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and European Jews in Cuba and Shanghai 1938-1943

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Refugees And Relief: The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee And European Jews In Cuba And Shanghai 1938-1943 Zhava Litvac Glaser Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/561 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] REFUGEES AND RELIEF: THE AMERICAN JEWISH JOINT DISTRIBUTION COMMITTEE AND EUROPEAN JEWS IN CUBA AND SHANGHAI 1938-1943 by ZHAVA LITVAC GLASER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the reQuirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ii © 2015 ZHAVA LITVAC GLASER All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation reQuirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dagmar Herzog ________________________ _________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt ________________________ _________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Jane S. Gerber Prof. Atina Grossmann Prof. Benjamin C. Hett Prof. Robert M. Seltzer Supervisory Committee The City University of -

The Greater (Grater) Divide: Considering Recent

4/22/2021 The Greater (Grater) Divide – Guernica COMMENTARY ARTS & CULTURE MENA June 19, 2017 The Greater (Grater) Divide Considering recent contemporary art in Israel. By Roslyn Bernstein 1 Raida Adon, "Strangeness" n the kitchen of the No Place Like Home exhibit at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where the I galleries are transformed into a domestic apartment, curator Adina Kamien-Kazhdan has installed a sculpture of a two-meter-high food grater. Entitled The Grater Divide (2002), the work, by Lebanese-born Palestinian-British artist Mona Hatoum, speaks to the current climate and context of Israeli contemporary art, where the Ministry of Culture has frequently clashed with left-leaning arts groups and where the effects of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, which tries to block Israeli artists and Israeli funded groups from exhibiting https://www.guernicamag.com/the-greater-grater-divide/ 1/11 4/22/2021 The Greater (Grater) Divide – Guernica globally, on the Israeli art world are being debated everywhere. Palestinian and Israeli artists alike are wrestling with issues of identity and home. Whether the venue is the Israel Museum, an international institution that receives less than 15 percent of its annual income from the state; the Petach Tikva Museum, funded by the municipality; the Ein Harod Museum, funded by kibbutzim; the Umm El Fahem Gallery of Palestinian Art, funded by the Israeli government; nonprot arts collectives, who piece together modest funding from diverse private and public sources; or commercial galleries who are in active pursuit of global collectors, funding is precarious, and political and economic issues are often inextricably intertwined with aesthetic concerns. -

The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 12-15-2020 The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Gideon Reuveni University of Sussex Diana University Franklin University of Sussex Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reuveni, Gideon, and Diana Franklin, The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism. (2021). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Edited by IDEON EUVENI AND G R DIANA FRANKLIN PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS | WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-711-9 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of librar- ies working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61249-703-7. Cover artwork: Painting by Arnold Daghani from What a Nice World, vol. 1, 185. The work is held in the University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep, Arnold Daghani Collection, SxMs113/2/90. -

HANAN 2 Chedet.Co.Cc February 19, 2009 by Dr. Mahathir Mohamad

HANAN 2 Chedet.co.cc February 19, 2009 By Dr. Mahathir Mohamad Dear Hanan, 1. I think I cannot convince you on anything simply because your perception of things is not based on logic or reason but merely on your strong belief that you are always right, even if the whole world says you are wrong. 2. Jews have lived with Muslims in Muslim countries for centuries without any serious problem. 3. On the other hand in Europe, Jews were persecuted. Every now and again there would be pogroms when the Europeans would massacre Jews. The Holocaust did not happen in Muslim countries. Muslims may discriminate against Jews but did not massacre them. 4. But now you are fighting the largely Muslim Palestinians. It cannot be because of religious differences or the killing of Jews living among them. It must be because you have taken their land and expelled them from their homeland. It is therefore not a religious war. But of course as you seek sympathisers from among the non-Muslims, the Palestinians seek sympathisers among the Muslims. That still does not make the war a religious war. 5. Whether you speak Hebrew or not is not relevant. Lots of people who are not English speak English. They don't belong to England. For centuries you could speak Hebrew but remained Germans, British, French, Russians etc. 6. Lots of Jews cannot speak Hebrew but they are still Jews. Merely being able to speak Hebrew does not entitle you to claim Palestine. 7. The Jews had lived in Europe for centuries. -

Historical Memory and History in the Memoirs of Iraqi Jews*

Historical Memory and History in the Memoirs of Iraqi Jews* Mark R. Cohen Memoirs, History, and Historical Memory Following their departure en masse from their homeland in the middle years of the twentieth century, Jews from Iraq produced a small library of memoirs, in English, French, Hebrew, and Arabic. These works reveal much about the place of Arab Jews in that Muslim society, their role in public life, their relations with Muslims, their involvement in Arab culture, the crises that led to their departure from a country in which they had lived for centuries, and, finally, their life in the lands of their dispersion. The memoirs are complemented by some documentary films. The written sources have aroused the interest of historians and scholars of literature, though not much attention has been paid to them as artifacts of historical memory.1 That is the subject of the present essay. Jews in the Islamic World before the Twentieth Century Most would agree, despite vociferous demurrer in certain "neo-lachrymose" circles, that, especially compared to the bleaker history of Jews living in Christian lands, Jews lived fairly securely during the early, or classical, Islamic * In researching and writing this paper I benefited from conversations and correspondence with Professors Sasson Somekh, Orit Bashkin, and Lital Levy and with Mr. Ezra Zilkha. Though a historian of Jews in the Islamic world in the Middle Ages, I chose to write on a literary topic in honor of Tova Rosen, who has contributed so much to our knowledge of another branch of Jewish literature written by Arab Jews. -

Staring Back at the Sun: Video Art from Israel, 1970-2012 an Exhibition and Public Program Touring Internationally, 2016-2017

Staring Back at the Sun: Video Art from Israel, 1970-2012 An Exhibition and Public Program Touring Internationally, 2016-2017 Roee Rosen, still from Confessions Coming Soon, 2007, video. 8:40 minutes. Video, possibly more than any other form of communication, has shaped the world in radical ways over the past half century. It has also changed contemporary art on a global scale. Its dual “life” as an agent of mass communication and an artistic medium is especially intertwined in Israel, where artists have been using video artistically in response to its use in mass media and to the harsh reality video mediates on a daily basis. The country’s relatively sudden exposure to commercial television in the 1990s coincided with the Palestinian uprising, or Intifada, and major shifts in internal politics. Artists responded to this in what can now be considered a “renaissance” of video art, with roots traced back to the ’70s. An examination of these pieces, many that have rarely been presented outside Israel, as well as recent, iconic works from the past two decades offers valuable lessons on how art and culture are shaped by larger forces. Staring Back at the Sun: Video Art from Israel, 1970-2012 traces the development of contemporary video practice in Israel and highlights work by artists who take an incisive, critical perspective towards the cultural and political landscape in Israel and beyond. Showcasing 35 works, this program includes documentation of early performances, films and videos, many of which have never been presented outside of Israel until now. Informed by the international 1 history of video art, the program surveys the development of the medium in Israel and explores how artists have employed technology and material to examine the unavoidable and messy overlap of art and politics. -

December Layout 1

AMERICAN & INTERNATIONAL SOCIETIES FOR YAD VASHEM Vol. 41-No. 2 ISSN 0892-1571 November/December 2014-Kislev/Tevet 5775 The American & International Societies for Yad Vashem Annual Tribute Dinner he 60th Anniversary of Yad Vashem Tribute Dinner We were gratified by the extensive turnout, which included Theld on November 16th was a very memorable many representatives of the second and third generations. evening. We were honored to present Mr. Sigmund Rolat With inspiring addresses from honoree Zigmund A. Rolat with the Yad Vashem Remembrance Award. Mr. Rolat is a and Chairman of the Yad Vashem Council Rabbi Israel Meir survivor who has dedicated his life to supporting Yad Lau — the dinner marked the 60th Anniversary of Yad Vashem and to restoring the place of Polish Jewry in world Vashem. The program was presided over by dinner chairman history. He was instrumental in establishing the newly Mark Moskowitz, with the Chairman of the American Society opened Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw. for Yad Vashem Leonard A. Wilf giving opening remarks. SIGMUND A. ROLAT: “YAD VASHEM ENSHRINES THE MILLIONS THAT WERE LOST” e are often called – and even W sometimes accused of – being obsessed with memory. The Torah calls on us repeatedly and command- ingly: Zakhor – Remember. Even the least religious among us observe this particular mitzvah – a true corner- stone of our identity: Zakhor – Remember – and logically L’dor V’dor – From generation to generation. The American Society for Yad Vashem has chosen to honor me with the Yad Vashem Remembrance Award. I am deeply grateful and moved to receive this honor. -

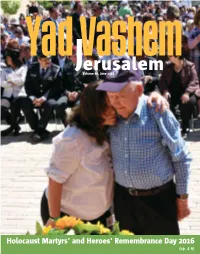

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

The Holocaust Encyclopedia

The Nuremberg Race Laws | The Holocaust Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nuremberg-r... THE NUREMBERG RACE LAWS The Nuremberg At the annual party rally Race Laws held in Nuremberg in 1935, the Nazis announced new laws which institutionalized many of the racial theories prevalent in Nazi ideology. The laws Massed crowds at the 1935 excluded German Jews Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg from Reich citizenship and prohibited them from marrying or having sexual relations with persons of "German or related blood." ! Feedback Ancillary ordinances to the laws disenfranchised Jews 1 of 4 11/19/18, 1:23 PM The Nuremberg Race Laws | The Holocaust Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nuremberg-r... and deprived them of most political rights. The Nuremberg Laws, as they became known, did not define a "Jew" as someone with particular religious beliefs. Instead, anyone who had three or four Jewish grandparents was defined as a Jew, regardless of whether that individual identified himself or herself as a Jew or belonged to the Jewish religious community. Many Germans who had not practiced Judaism for years found themselves caught in the grip of Nazi terror. Even people with Jewish grandparents who had converted to Christianity were defined as Jews. For a brief period after Nuremberg, in the weeks before and during the 1936 Olympic Games held in Berlin, the Nazi regime actually moderated its anti-Jewish attacks and even removed some of the signs saying "Jews Unwelcome" from public places. Hitler did not want international criticism of his government to result in the transfer of the Games to another country.