Gennan Exiles in the >Orient<

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being a Yekke Is a Really Big Deal for My Mum! on the Intergenerational Transmission of Germanness Amongst German Jews in Israel

Austausch, Vol. 2, Issue 1, July 2013 Being a Yekke is a really big deal for my mum! On the intergenerational transmission of Germanness amongst German Jews in Israel Dani Kranz (University of Erfurt, [email protected]) Throughout history, Germans1 have left German territory2 for different destinations worldwide, including: Eastern Europe; the United States; Australia, Africa and South America. Germans now constitute a global diaspora (cf. Schulze et. al. 2008). The vast majority of emigrants left German territory to seek a better life abroad. The new destinations attracted German emigrants with a mix of push and pull factors, with pull factors dominating. In the case of German emigrants there are sources depicting the maintenance and the transmission of Germanness, yet one group remains under-researched in this respect. This group is that of the German Jews.3 This article offers an in-depth, cross-generational case study of the transmission of Germanness of these ‘other Germans’ in the British mandate of Palestine and later Israel. While many German Jews left for the same destinations as other – non-Jewish - German emigrants, only a small number emigrated to the British mandate of Palestine (Rosenstock 1956, Stone 1997, Wormann 1970). By and large the vast bulk of all Jews from Germany fled to the British mandate as an effect of Nazi terror. Unlike previous waves of emigration, this move was forced upon them. It caused trauma (Viest 1977: 56) because it was determined by push factors, not by pull factors. This means that the vast majority of all German Jews who came to the British mandate of Palestine were refugees (Gelber & Goldstern 1988; Sela-Sheffy 2006, 2011; Viest 1977). -

The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 12-15-2020 The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Gideon Reuveni University of Sussex Diana University Franklin University of Sussex Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reuveni, Gideon, and Diana Franklin, The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism. (2021). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Edited by IDEON EUVENI AND G R DIANA FRANKLIN PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS | WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-711-9 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of librar- ies working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61249-703-7. Cover artwork: Painting by Arnold Daghani from What a Nice World, vol. 1, 185. The work is held in the University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep, Arnold Daghani Collection, SxMs113/2/90. -

Graduate Center. Spring 2018. Doctoral Program in History

1 City University of New York – Graduate Center. Spring 2018. Doctoral Program in History/Master’s Program in Middle Eastern Studies Room: Course Number: HIST 78110/MES 74500 Tuesday: 6:30 – 8:30 PM. Course Instructor: Simon Davis, [email protected] Office Phone: (718) 289 5677. Palestine Under The British Mandate: Origins, Evolutions and Implications, 1906-1949. This course examines how and with what consequences British interests at the time of the First World War identified and pursued control over Palestine, the subsequent forms such projections took, the crises which followed and their eventual consequences. Particular themes will be explored through analytical discussions of assigned historiographic materials, chiefly recent journal literature. Learning Objectives: Students will be encouraged to evaluate still-contested historical phenomena such as British undertakings with Zionism, colonialist relationships with Arab Palestine, institution-making and economic development, social and cultural transformations, resistance and political violence. This will be understood in the broader context of Middle Eastern politics in the era of late European colonial imperialism. Consonant and particular local experience in Palestine will also be addressed, exploring the effect of British Mandatory administration, especially in ethnic and sectarian-inflected questions of status, social and material conditions, identity, community, law and justice, expression and political rights. Finally, how and why did the Mandate end in a British debacle, Zionist triumph and Arab Palestinian catastrophe, with what main legacies resulting? On the basis of these studies students will each complete a research essay from the list below, along with a number of smaller critical exercises, and a final examination. -

The Memory of North African Jews in the Diaspora by Mechtild Gilzmer

The Memory of North African Jews in the Diaspora by Mechtild Gilzmer Abstract In the following contribution, I will approach in three steps the construction of memory by North-African Jews in the Diaspora. I will first trace the history and historiography of Jews in Arab countries and point out their characteristics. This will lead me to look more precisely at the concept of “Sephardic Jews,” its meaning and application as a key-notion in the memory building for Jews from Arab countries in the Diaspora nowadays. As literature and filmmaking hold a crucial role in the perception and transmission of memory,1 I will then present the works of two Jewish women artists, one living in France and the other living in Quebec, both with North African origins. I will try to show how they use the past for identity (de-)construction and compare their approaches. I choose the two examples because they illustrate two extremely opposed positions concerning the role of cultural identity. Standing in the intersection of history and literary studies, my interdisciplinary work considers literary and film as memory archives and subjective representations of the past not as historical sources. In referring to Jews in Arab countries this means in my article more precisely to look at the North-African Jews. That is why my article treats the following aspects: 1. Jews in Arab lands. A Historiographical Overview 2. A Special Case: “Sephardic Jews” 3. Jews from Arab Lands in the Diaspora - Literature as “lieu de mémoire” of Sephardic Identity in France. - The Example of Eliette Abécassis’ Novel “Sépharade” (2009). -

Gershom Biography an Intellectual Scholem from Berlin to Jerusalem and Back Gershom Scholem

noam zadoff Gershom Biography An Intellectual Scholem From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back gershom scholem The Tauber Institute Series for the Study of European Jewry Jehuda Reinharz, General Editor ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Associate Editor Sylvia Fuks Fried, Associate Editor Eugene R. Sheppard, Associate Editor The Tauber Institute Series is dedicated to publishing compelling and innovative approaches to the study of modern European Jewish history, thought, culture, and society. The series features scholarly works related to the Enlightenment, modern Judaism and the struggle for emancipation, the rise of nationalism and the spread of antisemitism, the Holocaust and its aftermath, as well as the contemporary Jewish experience. The series is published under the auspices of the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry —established by a gift to Brandeis University from Dr. Laszlo N. Tauber —and is supported, in part, by the Tauber Foundation and the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com Noam Zadoff Gershom Scholem: From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back *Monika Schwarz-Friesel and Jehuda Reinharz Inside the Antisemitic Mind: The Language of Jew-Hatred in Contemporary Germany Elana Shapira Style and Seduction: Jewish Patrons, Architecture, and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Sylvia Fuks Fried, and Eugene R. Sheppard, editors The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz Immanuel Etkes Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady: The Origins of Chabad Hasidism *Robert Nemes and Daniel Unowsky, editors Sites of European Antisemitism in the Age of Mass Politics, 1880–1918 Sven-Erik Rose Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 ChaeRan Y. -

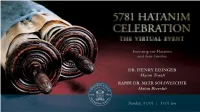

Hatan Torah Hatan Bereshit

honoring our Hatanim and their families DR. HENRY EDINGER Hatan Torah RABBI DR. MEIR SOLOVEICHIK Hatan Bereshit Sunday, 11/01 | 11:01 am Our Board of Trustees wishes our stellar 5781 Hatanim: Hazakim u’Berukhim! Louis M. Solomon, Parnas Michael Katz Oliver Stanton Karen Daar, Segan David J. Nathan, Honorary Parnas L. Stanton Towne Michael P. Lustig, Segan Avery Neumark Mark Tsesarsky Dr. Victoria R. Bengualid Peter Neustadter, Honorary Parnas David E.R. Dangoor Zoya Raynes Clerk: Leah Albek Seth Haberman David Sable Treasurer: Bruce Roberts The Solomon Family, on behalf of the Synagogue's Board of Trustees and the entire Congregation, congratulate themselves for the great good fortune of having such stellar Hatanim for 5781. May we merit seeing our Hatanim and their wonderful families at Synagogue, in person, soon. Congratulations and mazal tob to the Hatanim, Dr. Henry Edinger and Rabbi Meir Soloveichik. The Stanton Family Mazal tob & Hazak u'Baruch to our Hatanim!! You are both exemplary gems for our Congregation! Michael, Rachel, Helena, Julia, Zander In honor of the CSI Hatanim And in gratitude for all of Rabbi Soloveichik's Torah during these times. Agus Family Exciting! Edifying! Exceptional! Every time hitting the mark! Thank you, Rabbi Soloveichik, for keeping our Jewish souls on fire! Linda & Howard Sterling Mazal Tob to the Hatanim! A most beautiful and meaningful honor! Esther & Bill Schulder Congratulations and very best wishes to our honorees and their families. The Daar Family In honor of Rabbi Meir Soloveichik & Layaliza Anne and Natalio Fridman Congratulations to our Hatanim! Madelene & Stan Towne Congratulations to the Hatanim! With our best wishes for continued good health and happiness. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION A vineyard surrounded by a fence is better than one without a fence. Do not, however, make the fence higher than what it is intended to protect; for then, if it should fall, it would crush the plants. —Avot d’Rav Natan rs Abrams is highly prized in Manchester for supporting local Mwomen to birth according to the heightened standards of bodily governance that define them as Haredi Jews – a minority that is commonly regarded as ‘ultra-Orthodox’ and ‘hard to reach’ in the UK, claims which are critiqued in this book. She’s frequently told by women ‘you don’t understand how nice it is to have a Jewish midwife who understands you’, which is reflected in the warm smiles and greetings she receives while we sit in the neighbourhood’s busy café. Mrs Abrams makes herself constantly available for local birthing women, but the value of her role extends to more serious issues that can involve contestations around the interpretations of bodily care upheld by practitioners of authoritative knowledge1 in biomedicine and Haredi Judaism: When they go over their due date, halachically [according to Jewish law] you shouldn’t and the doctors will still pressurise, ‘we’ve got to induce you, you’re over your due date’. But the woman will ask the rabbi and if he says no, she won’t do it. You’re never compris- ing health, if it’s medically something, everybody understands. I think [her role] it’s to advocate where they are coming from. (Mrs Abrams) "Making Bodies Kosher: The Politics of Reproduction among Haredi Jews in England" by Ben Kasstan is available open access under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. -

SHEER GANOR CV [email protected]

SHEER GANOR CV [email protected] EDUCATION University of California, Berkeley Ph.D. in History with focus on Modern European History and Jewish History 2013-2019 Dissertation: In Scattered Formation: Displacement, Alignment and the German-Jewish Diaspora University of California, Berkeley M.A. in History with focus on Modern European History and Jewish History 2015 Tel Aviv University B.A. in History and General Studies 2011 PUBLICATIONS “Forbidden Words, Banished Voices: Jewish Refugees at the Service of BBC Propaganda to Wartime Germany.” In: Journal of Contemporary History (available online, forthcoming in print) “Generation in-flux: Diasporic reflections on the future of German-Jewishness.” In: Gideon Reuveni (ed.), The Future of the German Jewish Past, Purdue University Press (forthcoming, 2019) “To Farm a Future: The Displaced Youth of Gross-Breesen.” In: Andrea Westermann and Onur Erdur (eds.), Migration and Knowledge Transfer, special edition of the German Historical Institute Bulletin Supplement (forthcoming, September 2019) TEACHING EXPERIENCE Course: The History and Practice of Human Rights Department of History, University of California, Berkeley Graduate Student Instructor Fall 2015 Course: Jewish Civilization: Modern Period Department of History, University of California, Berkeley Graduate Student Instructor Spring 2015 Course: History of the Holocaust Department of History, University of California, Berkeley Graduate Student Instructor Fall 2014 SELECT FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS • Dissertation Completion Fellowship, Association -

Fragile Traces, Treacherous Sands: Ronen Sharabani and Micha Ullman's Intergenerational Encounter

arts Article Fragile Traces, Treacherous Sands: Ronen Sharabani and Micha Ullman’s Intergenerational Encounter Hava Aldouby Department of Literature, Language, and the Arts, The Open University of Israel, Ra’anana 4353701, Israel; [email protected] Received: 18 March 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 23 June 2020 Abstract: This paper addresses an intriguing intergenerational encounter between Micha Ullman (b. Tel Aviv 1939), one of Israel’s most prominent senior artists, and Ronen Sharabani (b. Tel Aviv 1974), a young media artist. The two artists’ otherwise divergent practices converge in their use of sand and red earth as their primary media. The paper brings Mieke Bal’s concept of migratory aesthetics and Jill Bennett’s phenomenological approach to trauma-related art to bear on Ullman’s fragile earth installations and perforated sand tables, and on Sharabani’s projections of Virtual Reality onto sand. Also addressed is Sharabani’s series Vitual Territories (2019), in which digitally manipulated views from Google Earth probe geographical sites that resonate with migratory histories. The paper traces two main trajectories upon which the oeuvres of Ullman and Sharabani interface. The first category, “treacherous sands”, relates to installations involving sand tables and other containers of soil. In turn, the category of “fragile traces” addresses installations that feature various architectural ground plans modeled in sand. In these installations, sand is the quintessential terra infirma. At the same time, however, the paper proposes that through the haptic appeal of the medium of sand, these installations counter the pervasive anxiety of shifting ground with an augmented sense of bodily presence. -

Congregation Sons of Israel

Congregation Sons of Israel THE MYERS FAMILY CAMPUS Congregation Sons of Israel CONTINUING THE VISION — BUILDING OUR FUTURE THE MYERS FAMILY CAMPUS CONTINUING THE VISION — BUILDING OUR FUTURE MARCH 2021 17 Adar - 18 Nisan 5781 THE RABBI’S CIRCLE LECTURE SERIES Wednesday, March 10th at 7:30pm Join us for a timely talk with Dr. Jonathan Sarna “White Supremacy and Antisemitism: Lessons from the Capitol Attack” Open to all. See Page 2. Learn SUNDAY, MARCH 14th at 1pm [VIRTUAL] PASSOVER SHOPPING EVENT AT MATANAH: The Sisterhood Gift Shop. See Page 14 Shop Sunday, March 21st at 4:30pm PASSOVER FOOD FOR See Page 19 THOSE IN NEED: HOW TO PARTICIPATE Schmooze See Page 7 Tikkun Olam PASSOVER UNIVERSITY IS COMING...PESACH PROGRAMMING STARTING ON THE EVENING OF MARCH 13TH. More information coming soon! The First Seder is March 27th Schedule of Services on Page 2. And More... Pesach guide starts on page 22. Celebrate Page 2 Congregation Sons of Israel March 2021 Congregation Sons of Israel 1666 Pleasantville Road Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510 PASSOVER SERVICES Phone: (914) 762-2700 Fax: (914) 941-3465 www.csibriarcliff.org Thursday 3/25 8am: Service for the Fast of the [email protected] First- Born OUR MISSION STATEMENT (Last Day to Sell Chametz) (adopted 1999, revised 2007): Congregation Sons of Israel is an egalitarian, Conservative Saturday 3/27: First Seder evening synagogue dedicated to impart- ing Jewish values and traditions Sunday 3/28 9:30am: Pesach Morning Service from generation to generation in Second Seder evening a welcoming participatory environment. We are a caring community committed to lifelong Monday 3/29 9:30am: Pesach Service Jewish learning, the observance of mitzvot, meaningful prayer Friday 4/2 6:30pm: Pesach Service and charitable deeds. -

A Smorgasbord of Jewish Ideas

A smorgasbord of Jewish ideas ing to the Jewish calendar – actual- ly face a much bigger challenge, I Israelis must be taught about think.” Relaxed in a dark suit without a Jewish culture, says Daniel Posen tie, Posen quietly contemplates his foundation’s work while sipping coffee at a Jerusalem hotel during a • BY STEVE LINDE itself, where, he said, most secular visit in January. Israelis know little or nothing about “The majority of Jews here and aniel Posen genuinely cares Judaism. around the world view themselves about Israel and the Jewish “The majority of Jews here are as secular,” he said. “We believe people. As CEO of the Po- missing part of their identity,” Po- that Judaism is first and foremost a sen Foundation, which he sen told The Jerusalem Post – “the culture. What do we do with the Jew Dfounded three decades ago with his part that comes through their cul- who says, ‘There’s nothing really for father, Felix, the cosmopolitan entre- ture and their own Jewishness. me because Judaism is for religious preneur and philanthropist strongly “I think the government has woe- Jews, or haredi Jews’? I think that’s a advocates spreading the values of Ju- fully failed to serve the majority of needless tragedy and something we daism as a culture, making Jewish her- Jews in this country,” he went on. should try to do something about, itage accessible to all. “Secular Israeli Jews are much more even in a small measure.” To Posen, lack of Jewish knowl- Jewishly impoverished than their Posen’s remedy? edge is a pervasive problem in the Diaspora counterparts,” Posen add- “Educate people, give them a Jewish world. -

JPS 174 Bibliography 1..19

Bibliography of Periodical Literature NORBERT SCHOLZ This section lists articles and reviews of books relevant to Palestine and the Arab-Israeli conflict. Entries are classified under the following headings: Reference and General; History (through 1948) and Geography; Palestinian Politics and Society; Jerusalem; Israeli Politics, Society, and Zionism; Arab and Middle Eastern Politics; International Relations; Law; Military; Economy, Society, and Education; Literature, Arts, and Culture; and Book Reviews. REFERENCE AND GENERAL Alvi, Hayat. “The Diffusion of Intra-Islamic Violence and Terrorism: The Impact of the Proliferation of Salafi/Wahhabi Ideologies.” MERIA 18, no. 2 (Sum. 14): 38–50. Karam, John T. “Philip Hitti, Brazil, and the Diasporic Histories of Area Studies.” IJMES 46, no. 3 (Aug. 14): 451–71. Khalidi, Walid. “Palestine and Palestine Studies: One Century after World War I and the Balfour Declaration.” JPS 44, no. 1 (Aut. 14): 137–47. Laroui, Abdallah (interview). “A Critique of Ideology” [in Arabic]. MA 37, no. 427 (Sep. 14): 142–54. al-Nahi, Haytham G. “Edward Said: Between Orientalism and Post-Orientalism” [in Arabic]. MA 37, no. 426 (Aug. 14): 55–69. HISTORY (THROUGH 1948) AND GEOGRAPHY Halperin, Liora R. “The Battle over Jewish Students in the Christian Missionary Schools of Mandate Palestine.” MES 50, no. 5 (14): 737–54. Kaufman, Ilana. “Communists and the 1948 War: PCP, Maki, and the National Liberation League.” JIsH 33, no. 2 (14): 115–44. Khatib, Muna H. “The Zionist Settlements as Seen in the Arab Press in Bilad al-Sham and Egypt (1909–1914): ‘A Jewish Government inside the Ottoman Government’” [in Arabic]. ShF, no.