327 Language Peculiarities of Regional British English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barrow-In-Furness, Cumbria

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria Shelfmark: C1190/11/01 Recording date: 2005 Speakers: Airaksinen, Ben, b. 1987 Helsinki; male; sixth-form student (father b. Finland, research scientist; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) France, Jane, b. 1954 Barrow-in-Furness; female; unemployed (father b. Knotty Ash, shoemaker; mother b. Bootle, housewife) Andy, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, shop sales assistant; mother b. Harrow, dinner lady) Clare, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; female; sixth-form student (father b. Barrow-in-Furness, farmer; mother b. Brentwood, Essex) Lucy, b. 1988 Leeds; female; sixth-form student (father b. Pudsey, farmer; mother b. Dewsbury, building and construction tutor; nursing home activities co-ordinator) Nathan, b. 1988 Barrow-in-Furness; male; sixth-form student (father b. Dalton-in-Furness, IT worker; mother b. Barrow-in-Furness) The interviewees (except Jane France) are sixth-form students at Barrow VI Form College. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♥ see Dictionary of Contemporary Slang (2014) ♦ see Urban Dictionary (online) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased chuffed; happy; made-up tired knackered unwell ill; touch under the weather; dicky; sick; poorly hot baking; boiling; scorching; warm cold freezing; chilly; Baltic◊ annoyed nowty∆; frustrated; pissed off; miffed; peeved -

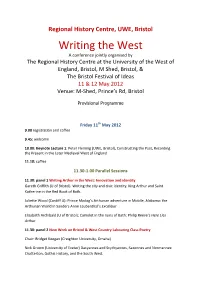

Writing the West Conference Programme

Regional History Centre, UWE, Bristol Writing the West A conference jointly organised by The Regional History Centre at the University of the West of England, Bristol, M Shed, Bristol, & The Bristol Festival of Ideas 11 & 12 May 2012 Venue: M‐Shed, Prince’s Rd, Bristol Provisional Programme Friday 11th May 2012 9.00 registration and coffee 9.45: welcome 10.00: Keynote Lecture 1: Peter Fleming (UWE, Bristol), Constructing the Past, Recording the Present in the Later Medieval West of England 11.10: coffee 11.30‐1.00 Parallel Sessions 11.30: panel 1 Writing Arthur in the West: Innovation and identity Gareth Griffith (U of Bristol): Writing the city and civic identity: King Arthur and Saint Katherine in the Red Book of Bath. Juliette Wood (Cardiff U): Prince Madog’s Arthurian adventure in Mobile, Alabama: the Arthurian World in Sanders Anne Laubenthal’s Excalibur Elizabeth Archibald (U of Bristol): Camelot in the ruins of Bath: Philip Reeve’s Here Lies Arthur 11.30: panel 2 New Work on Bristol & West Country Labouring Class Poetry Chair: Bridget Keegan (Creighton University, Omaha) Nick Groom (University of Exeter) Dacyannes and Scythyannes, Saxonnes and Normannes: Chatterton, Gothic History, and the South West. Kerri Andrews, (Strathclyde University), Ann Yearlsey, a Bristol Poet. John Goodridge (Nottingham Trent), John Gregory: sonnets, shoemaking and socialism 1.00pm Lunch 2.00‐3.30 Parallel Sessions 2.00‐3.30 panel 1: Landscape, Nature and Place Dave Postles (University of Leicester) Trickster in the Wiltshire landscape: E. M. Forster and The Longest Journey Richard Coates (UWE, Bristol) ‘Bent on emptying his note‐book in decent English’: Richard Jefferies, naturalistic observation, and English dialect. -

Introduction SLICE 1

Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe Book series: Standard Language Ideology in Contemporary Europe Editors: Nikolas Coupland and Tore Kristiansen –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1. Tore Kristiansen and Nikolas Coupland (Eds.): Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe. 2011. Tore Kristiansen and Nikolas Coupland (Eds.) Standard Languages and Language Standards in a Changing Europe NOVUS PRESS OSLO – 2011 Printed with economic support from ..... © Novus AS 2011. Cover: Geir Røsset ISBN: 978-82-7099-659-9 Print: Interface Media as, Oslo. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Novus Press. Acknowledgements This first publication from the SLICE group (Standard Language Ideology in Contemporary Europe) and in its book series has only been possible as a result of much interest and support – which we wish to acknowledge here. The initiative towards the SLICE programme was taken at the LANCHART centre (dgcss.hum.ku.dk). The idea was discussed with members of LANCHART’s International Council at the centre’s annual meeting with the council in 2008, involving Peter Auer, Niko- las Coupland, Paul Kerswill, Dennis R Preston, Mats Thelander, and Helge Sandøy – as well as Peter Garrett as a specially invited ‘sparring partner’. Subsequently, a proposal for a series of Exploratory Workshops was worked out at LANCHART by Frans Gregersen, Tore Kris- tiansen, Shaun Nolan, and Jacob Thøgersen. This volume results from two Exploratory Workshops which were held in Copenhagen, Denmark in February and August of 2009. -

Have No Idea Whether That's True Or Not": Belief and Narrative Event Enactment 3-14 JAMES G

- ~ Volume 9, Number 2 June 1990 CONTENTS KEITH CUNNINGHAM "I Have no Idea Whether That's True or Not": Belief and Narrative Event Enactment 3-14 JAMES G. DELANEY Collecting Folklore in Ireland 15-37 SYLVIA FOX Witch or Wise Women?-women as healers through the ages 39-53 ROBERT PENHALLURICK The Politics of Dialectology 55-68 J.M. KIRK Scots and English in the Speech and Writing of Glasgow 69-83 Reviews 85-124 Index of volumes 8 and 9 125-128 ISSN 0307-7144 LORE AND LANGUAGE The J oumal of The Centre for English Cultural Tradition and Language Editor J.D.A. Widdowson © Sheffield Acdemic Press Ltd, 1990 Copyright is waived where reproduction of material from this Journal is required for classroom use or course work by students. SUBSCRIPTION LORE AND LANGUAGE is published twice annually. Volume 9 (1990) is: Individuals £16.50 or $27.50 Institutions £50.00 or $80.00 Subscriptions and all other business correspondence shuld be sent to Sheffield Academic Press, 343 Fulwood Road, Sheffield S 10 3BP, England. All previous issues are still available. The opinions expressed in this Journal are not necessarily those of the editor or publisher, and are the responsibility of the individual authors. Printed on acid-free paper in Great Britian by The Charlesworth Group, Huddersfield [Lore & Language 9/2 (1990) 3-14] "I Have No Idea Whether That's True or Not": Belief and Narrative Event Enactment Keith Cunningham A great deal of scholarly attention has in recent years been directed toward a group of traditional narratives told in British and Anglo-American cultures1 which have been called "contemporary legend" ,2 "urban legend" ,3 and "modem myth". -

The Sound of William Barnes's Dialect Poems

Welcome to the electronic edition of The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems: 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection (1862). The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection About this volume This is the third volume in a series that sets out to provide a phonemic transcript and an audio recording of each individual poem in Barnes’s three collections of Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect. Its 96 poems include some of those most loved and admired: poems of heart-wrenching grief at the untimely deaths of Barnes’s wife, Julia (“Woak Hill”), and their young son, Julius “The turnstile”); celebrations of love anticipated (“In the spring”) and love fulfilled (“Don’t ceäre”); protests against injustice and snobbery (“The love child”); struggles to accept God’s will (“Grammer a-crippled”); comic poems (“John Bloom in Lon’on”, “A lot o’ maïdens a-runnèn the vields”); and poems on numerous other subjects, with an emotional range stretching from the deepest of grief to the highest of joy. The metrical forms show astonishing versatility, from straightforward octosyllabic couplets to challenging rhyme-schemes and innovative stanzaic patterns, widely varied line-lengths, and skilful adaptations of rhetorical devices from other languages. -

Accent Change in Glaswegian Final Results For

THE GLASGOW SPEECH PROJECT Accent change in Glaswegian (1997 corpus) Results for Consonant Variables Claire Timmins*, Fiona Tweedie+, and Jane Stuart-Smith* *Department of English Language, University of Glasgow +Department of Statistics, University of Edinburgh 7 September 2004 Department of English Language, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ Accent change in Glaswegian (1997 corpus): Results for Consonant Variables 0. Introduction This document presents the main results from the first project of the long-term research programme which we call The Glasgow Speech Project. Here we give selected results from the formal statistical analysis of the 11 consonantal variables which were auditorily transcribed from the set of socially-stratified recordings made in the spring and summer of 1997 in Glasgow. 32 informants were involved, divided equally according to age (older: 40-60 years; younger: 13-14 years old), gender, and socio-economic background (middle-class and working-class). Further details of the data collection including informant sample and general methodology may be found in Stuart-Smith (1999); (2003); Stuart-Smith and Tweedie (2000). The main analysis of these data was carried out as part of the project, Accent Change in Glaswegian: A sociophonetic investigation (1999), funded by the Leverhulme Trust, and subsequent analysis was supported by the AHRB (2002). Variables from the wordlists were auditorily transcribed by Claire Timmins from segmented word files which had been digitized into a PC running Entropic's xwaves+ with a sampling rate of 16kHz at 16 bits. Variables from the conversations were auditorily transcribed by Claire Timmins from DAT recordings using Panasonic headphones on a Sony desktop DAT recorder. -

The Sound of William Barnes's Dialect Poems

Welcome to the electronic edition of The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems: 2. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, second collection (1859). The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems 2. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, second collection About this volume This is the second volume in a series that sets out to to provide a phonemic transcript and an audio recording of each individual poem in Barnes’s three collections of Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect. Beginning with two poems that inspired Vaughan Williams to set them to music, and ending with a paean of praise for the poet’s native county, this second collection contains 105 poems of immense range and power. There are poems of longing, of love and of loss; of pain and of protest; of tears and of laughter; of grief and consolation; of feasting and celebration; of music and birdsong; of falsehood and friendship and faith; of generosity and meanness; of bad temper and good; of stasis and travel; of flowers and trees; of storm and of calm. “Here,” in short, (as Dryden famously said of the poetry of Geoffrey Chaucer) “is God’s plenty”. -

Reference Guide for Varieties of English 1 General

Reference guide for varieties of English Outline structure 1 General 1.1 Investigating variation 1.1 Language change 1.2 Standard English 1.4 Nonstandard English 1.5 Historical background 2 England 2.1 Overviews 2.2 Received Pronunciation 2.3 Estuary English 2.4 Cockney 2.5 British Creole 2.6 East Anglia 2.7 South of England 2.8 West and South-West 2.9 Northern English 2.10 Other languages in Britain 3 The Celtic realms 3.1 Scotland 3.2 Wales 3.3 Ireland 3.4 Isle of Man 4 Minor European varieties 4.1 Channel Islands 4.2 Gibraltar 4.3 Malta 5 The New World 5.1 American English 5.2 Canadian English 5.3 Caribbean English 6 English in Africa 6.1 West Africa 6.2 East Africa 6.3 Southern Africa 6.4 The South Atlantic 7 English in Asia 7.1 South Asia 7.2 South-East Asia 7.3 East Asia 8 Australasia and Pacific 8.1 Australia 8.2 New Zealand 8.3 The anglophone Pacific 9 English-based pidgins and creoles 10 World Englishes 10.1 English and colonialism 10.2 ‘New Englishes’ 10.3 Nonnative Englishes 1 General Aarts, Bas and April McMahon (eds) 2006. The Handbook of English Linguistics. Oxford / Malden, MA: Blackwell. Allen, Harold B. and Michael D. Linn (eds) 1986. Dialect and Language Variation. Orlando: Academic Press. Anderson, Peter M. 1987. A Structural Atlas of the English Dialects. London. Raymond Hickey Reference guide for varieties of English Page 2 of 61 Auer, Peter, Frans Hinskens and Paul Kerswill (eds) 2000. -

A Glasgow Voice

A Glasgow Voice A Glasgow Voice: James Kelman’s Literary Language By Christine Amanda Müller A Glasgow Voice: James Kelman’s Literary Language, by Christine Amanda Müller This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Christine Amanda Müller All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2945-5, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2945-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables.............................................................................................. ix Abstract ..................................................................................................... xii Declaration ............................................................................................... xiii Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xiv Chapter One................................................................................................. 1 Introduction James Kelman’s writing and aims Weber’s notion of social class Kelman’s treatment of narrative Traditional bourgeois basis of book publication Scottish literary renaissance The Glaswegian dialect and the -

A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction Jones, Benjamin A. How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Jones, Benjamin A. (2018) A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction. Doctoral thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa44723 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ A history of the Welsh English dialect in fiction Benjamin Alexander Jones Submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements -

Dialect, Adaptation and Assimilation in the Poetry of William Barnes and Thomas Hardy

Dialect, Adaptation and Assimilation in the Poetry of William Barnes and Thomas Hardy Heather Hawkins* The Dorset poets William Barnes and Thomas Hardy lived during a period of great social and economic change in nineteenth-century Britain, change triggered by enclosure and the gradual machinisation of farming. This caused the rapid disappearance of rural culture, something of which Barnes and Hardy would have been acutely aware, as both of their families occupied an ambiguous class position; though elevated from the majority of the labouring class by their employment and education, they were not wealthy enough to join the middle class. A close reading of Barnes’s poem ‘Woak Were Good Enough Woonce’ and Hardy’s poem ‘Silences’ illustrates the poets’ contrasting approaches to dialect in poetry, and reveals their different responses to the effects of the increased urbanisation of rural culture. In particular, an examination of the use of dialect in these poems offers interesting insights into the processes of cultural adaptation and assimilation which were brought about by such changes. The enclosure of land in the early 1800s and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 forced many small tenant farmers out of business, and led to an increase in rural unemployment and a subsequent migration of labourers to urban centres. This influx of workers indicated the ability of the rural labourer to adapt to social and economic change.1 However, the rural labourer, or ‘Hodge’ as he was dubbed by social commentators of the period, was typically presented in contemporary literature as slow, awkward, lacking in social ambition and only able to converse in an unintelligible language. -

A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova

A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova EDINBURGH TEXTBOOKS ON THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE – ADVANCED A Historical Phonology of English Edinburgh Textbooks on the English Language – Advanced General Editor Heinz Giegerich, Professor of English Linguistics, University of Edinburgh Editorial Board Laurie Bauer (University of Wellington) Olga Fischer (University of Amsterdam) Rochelle Lieber (University of New Hampshire) Norman Macleod (University of Edinburgh) Donka Minkova (UCLA) Edgar W. Schneider (University of Regensburg) Katie Wales (University of Leeds) Anthony Warner (University of York) TITLES IN THE SERIES INCLUDE: Corpus Linguistics and the Description of English Hans Lindquist A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova A Historical Morphology of English Dieter Kastovsky Grammaticalization and the History of English Manfred Krug and Hubert Cuyckens A Historical Syntax of English Bettelou Los English Historical Sociolinguistics Robert McColl Millar A Historical Semantics of English Christian Kay and Kathryn Allan Visit the Edinburgh Textbooks in the English Language website at www. euppublishing.com/series/ETOTELAdvanced A Historical Phonology of English Donka Minkova © Donka Minkova, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LF www.euppublishing.com Typeset in 10.5/12 Janson by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 3467 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3468 2 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 3469 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 0 7486 7755 9 (epub) The right of Donka Minkova to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.