Reference Guide for Varieties of English 1 General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An English Speaking Country Ghana

Ghana – an English speaking country A global perspective in English classes Finanziert durch: Pia Kranz Esther Mumuni Introduction Table of contents Introduction 2 Chapter schedule 5 Chapter 1: First steps into Ghana (B1) 6 On DVD: Pictures to Main exercise C Chapter 2: Weekdays in Ghana (A2) 21 On DVD: Pictures to Main exercise A Chapter 3: Globalisation on Ghana’s markets and Ghanaian culinary art (B1) 32 On DVD: Pictures to Introduction A, Exercise A, Conclusion Chapter 4: The impact of festivals and traditions in the Ghanaian and German culture (B1) 44 On DVD: Pictures to Introduction A, Main exercise A Chapter5: Business location Ghana – The consequences of economic growth, gold mining and tourism (B2) 57 Chapter 6: Cocoa production in Ghana (B2) 73 On DVD: Pictures to Main exercise B Chapter 7: Conservation of natural resources – A global responsibility (B2) 83 On DVD: Pictures to Introduction A Chapter 8: What is culture? New perspectives on Ghana and Germany (B2) 91 Chapter 9: Modern media – Electrical explosion in the world and it effects on Ghana (C1) 102 On DVD: Pictures to Main exercise B Ghana – an English speaking country | dvv international 2013 | 1 Introduction Introduction This English book is addressed to English teachers in adult education centres and provides an opportunity to integrate global learning into language courses with the main focus on language acquisition In an age of globalisation the world is drawing closer together and ecological and economic sustainable development has become -

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

APPENDIX. Philip Baker (1940-2017) Bibliography of His Publications, 1969-2017

Coversheet This is the accepted manuscript (post-print version) of the article. Contentwise, the accepted manuscript version is identical to the final published version, but there may be differences in typography and layout. How to cite this publication Please cite the final published version: Bakker, P. (2018). Obituary Philip Baker. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 33(2), 231-239. DOI: 10.1075/jpcl.00014.obi Publication metadata Title: Obituary Philip Baker Author(s): Peter Bakker Journal: Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages DOI/Link: 10.1075/jpcl.00014.obi Document version: Accepted manuscript (post-print) General Rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. If the document is published under a Creative Commons license, this applies instead of the general rights. This coversheet template is made available by AU Library Version 2.0, December 2017 Obituary Philip Baker (with a bibliography of his writings, not included in the printed version). -

Multicultural London English

Multicultural London English Multicultural London English Below are links to two recent newspaper articles about Multicultural London English. Text A is from The Guardian’s Education pages, first published in 2006. Text B is from The Daily Mail, first published in 2013. Text A: www.theguardian.com/education/2006/apr/12/research.highereducation Text B: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2498152/Is-end-Cockney-Hybrid- dialect-dubbed-Multicultural-London-English-sweeps-country.html Task one – the titles Looking closely at the titles of the two articles, compare how language is used to present the topic. Complete the table with examples and comments on the differences. Text B: ‘Is this the end of Text A: ‘Learn Jafaikan in two Cockney? Hybrid dialect dubbed minutes’ ‘Multicultural London English’ sweeps across the country’ Sentence functions Name used for new variety of English Lexis with negative connotations Discourse: what does each title suggest the article’s stance on MLE will be? © www.teachit.co.uk 2017 28425 Page 1 of 7 Multicultural London English Task two – lexical choices Both texts use the nickname ‘Jafaikan’. Text A mentions the term in the title and later in the body of the article: ‘One schoolteacher has used the term ‘Jafaikan’ to describe the new language, but the researchers insist on more technical terminology: ‘multicultural London English’.’ Text B states ‘It was originally nicknamed Jafaican - fake Jamaican - but scientists have now said it is a dialect that been influences [sic] by West Indian, South Asian, Cockney and Estuary English.’ 1. What is the effect of Text A’s attribution (even though it is done anonymously) for the origin of the name compared to Text B’s use of a passive sentence ‘It was originally nicknamed …’? 2. -

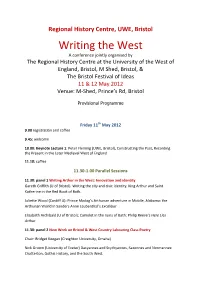

Writing the West Conference Programme

Regional History Centre, UWE, Bristol Writing the West A conference jointly organised by The Regional History Centre at the University of the West of England, Bristol, M Shed, Bristol, & The Bristol Festival of Ideas 11 & 12 May 2012 Venue: M‐Shed, Prince’s Rd, Bristol Provisional Programme Friday 11th May 2012 9.00 registration and coffee 9.45: welcome 10.00: Keynote Lecture 1: Peter Fleming (UWE, Bristol), Constructing the Past, Recording the Present in the Later Medieval West of England 11.10: coffee 11.30‐1.00 Parallel Sessions 11.30: panel 1 Writing Arthur in the West: Innovation and identity Gareth Griffith (U of Bristol): Writing the city and civic identity: King Arthur and Saint Katherine in the Red Book of Bath. Juliette Wood (Cardiff U): Prince Madog’s Arthurian adventure in Mobile, Alabama: the Arthurian World in Sanders Anne Laubenthal’s Excalibur Elizabeth Archibald (U of Bristol): Camelot in the ruins of Bath: Philip Reeve’s Here Lies Arthur 11.30: panel 2 New Work on Bristol & West Country Labouring Class Poetry Chair: Bridget Keegan (Creighton University, Omaha) Nick Groom (University of Exeter) Dacyannes and Scythyannes, Saxonnes and Normannes: Chatterton, Gothic History, and the South West. Kerri Andrews, (Strathclyde University), Ann Yearlsey, a Bristol Poet. John Goodridge (Nottingham Trent), John Gregory: sonnets, shoemaking and socialism 1.00pm Lunch 2.00‐3.30 Parallel Sessions 2.00‐3.30 panel 1: Landscape, Nature and Place Dave Postles (University of Leicester) Trickster in the Wiltshire landscape: E. M. Forster and The Longest Journey Richard Coates (UWE, Bristol) ‘Bent on emptying his note‐book in decent English’: Richard Jefferies, naturalistic observation, and English dialect. -

ENGLISH EXPRESSIONS in GHANA's PARLIAMENT Halimatu

International Journal of English Language and Linguistics Research Vol.5, No.3, pp. 49-63, June 2017 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ENGLISH EXPRESSIONS IN GHANA’S PARLIAMENT Halimatu Sardia Jibril and Nana Yaw Ofori Gyasi Accra College of Education, Accra Koforidua Technical University, Koforidua ABSTRACT: This paper takes a look at the English language spoken on the floor of parliament by Ghanaian parliamentarians. It attempts to ascertain the English features of Ghanaian parliamentarians and whether the identified features can be described as Ghanaian English. The study was guided by the syntactic features given as typical of WAVE (Bokamba, 1991) and the grammatical description of African Englishes (Schmied, 1991) and a careful reading of the Hansard which is the daily official report of parliamentary proceeding. It is revealed that the English spoken by Ghanaian parliamentarians has identifiable Ghanaian features that can support the claim that their English is typically Ghanaian. KEYWORDS: Ghanaian English, Expression, Language, Parliament, Hansard INTRODUCTION From the discussions over the last two decades, English is now the world’s language. It plays very useful roles in the lives of people and nations across the world. Studies have shown that English is the most commonly spoken and taught foreign language in the world today. In every country in the world recently, English is at least used by some people among the population for some purposes. It is interesting to note that English is a very important language in Francophone West Africa such as Togo (Awuku, 2015); it plays a major role in the Middle East such as Kuwait (Dashti, 2015); and some companies in Japan have adopted English as an in-house lingua franca (Inagawa, 2015). -

17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 World Englishes and their dialect roots Schreier, Daniel Abstract: This chapter investigates the persistence and development of so-called dialect roots, that is, features of local forms of British English that are transplanted to overseas territories. It discusses dialect input and the survival of features, independent developments within overseas communities, including realignments of features in the dialect inputs, as well as contact phenomena when English speakers interact with those of other dialects and languages. The diagnostic value of these roots is exemplified with selected cases from around the world (Newfoundland English, Liberian English, Caribbean Englishes), which are assessed with reference to the archaic/dynamic character of individual features in new-dialect formation and language-contact scenarios. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-198161 Book Section Published Version The following work is licensed under a Publisher License. Originally published at: Schreier, Daniel (2020). World Englishes and their dialect roots. In: Schreier, Daniel; Hundt, Marianne; Schneider, Edgar W. The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 384-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots Daniel Schreier World Englishes developed out of English dialects spoken throughout the British Isles. These were transported all over the globe by speakers from different regions, social classes, and educational backgrounds, who migrated with distinct trajectories, for various periods of time and in distinct chronolo- gical phases (Hickey, Chapter 2, this volume; Britain, Chapter 7,thisvolume). -

Attitudes Towards English in Ghana Kari Dako

Dako & Quarcoo / Legon Journal of the Humanities (2017) 20-30 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v28i1.3 Attitudes towards English in Ghana Kari Dako Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana [email protected]; [email protected] Millicent Akosua Quarcoo Senior Lecturer, Department of English Education, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana [email protected]; [email protected] Submitted: May 16, 2014 /Accepted: September 4, 2014 / Published: May 31, 2017 Abstract The paper considers official and individual attitudes towards bilingualism in English and a Ghanaian language. We ask whether bilingualism in English and Ghanaian languages is a social handicap, without merit, or an important indicator of ethnic identity. Ghana has about 50 non-mutually intelligible languages, yet there are no statistics on who speaks what language(s) where in the country. We consider attitudes to English against the current Ghanaian language policy in education as practised in the school system. Our data reveal that parents believe early exposure to English enhances academic performance; English is therefore becoming the language of the home. Keywords: attitudes, English, ethnicity, Ghanaian languages, language policy Introduction Asanturofie anomaa, wofa no a, woafa mmusuo, wogyae no a, wagyae siadeé. (If you catch the beautiful nightjar, you inflict on yourself a curse, but if you let it go, you have lost something of great value). The attitude of Ghanaians to English is echoed in the paradox of this well-known Akan proverb. English might be a curse but it is at the same time a valuable necessity. Attitudes are learned, and Garret (2010) reminds us that associated with attitudes are ‘habits, values, beliefs, opinions as well as social stereotypes and ideologies’ (p.31). -

Southern Bahamian: Transported African American Vernacular English Or Transported Gullah?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Southern Bahamian: Transported African American Vernacular English or Transported Gullah? Stephanie Hackert University of Augsberg1 John A. Holm University of Coimbra ABSTRACT The relationship between Bahamian Creole English (BahCE) and Gullah and their historical connection with African American Vernacular English (AAVE) have long been a matter of dispute. In the controversy about the putative creole origins of AAVE, it was long thought that Gullah was the only remnant of a once much more widespread North American Plantation Creole and southern BahCE constituted a diaspora variety of the latter. If, however, as argued in the 1990s, AAVE never was a creole itself, whence the creole nature of southern BahCE? This paper examines the settlement history of the Bahamas and the American South to argue that BahCE and Gullah are indeed closely related, so closely in fact, that southern BahCE must be regarded as a diaspora variety of the latter rather than of AAVE. INTRODUCTION English (AAVE) spoken by the slaves Lexical and syntactic studies of Bahamian brought in by Loyalists after the Creole English (Holm, 1982; Shilling, 1977) Revolutionary War that predominated over led Holm (1983) to conclude that on southern the variety that had developed largely on the Bahamian islands such as Exuma, it was northern Bahamian islands. This ascendancy mainland African American Vernacular developed “…for the simple reason that it had 1 Stephanie Hackert, Applied English Linguistics, University of Augsburg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] John A. Holm, University of Coimbra, Portugal E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements: An earlier draft of this article benefited from the comments of Katherine Green, Salikoko Mufwene, Edgar Schneider and Donald Winford, whom we would like to thank here, while noting that responsibility for any remaining shortcomings is solely our own. -

The Sound of William Barnes's Dialect Poems

Welcome to the electronic edition of The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems: 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection (1862). The book opens with the bookmark panel and you will see the contents page. Click on this anytime to return to the contents. You can also add your own bookmarks. Each chapter heading in the contents table is clickable and will take you direct to the chapter. Return using the contents link in the bookmarks. The whole document is fully searchable. Enjoy. The Sound of William Barnes’s Dialect Poems 3. Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect, third collection About this volume This is the third volume in a series that sets out to provide a phonemic transcript and an audio recording of each individual poem in Barnes’s three collections of Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect. Its 96 poems include some of those most loved and admired: poems of heart-wrenching grief at the untimely deaths of Barnes’s wife, Julia (“Woak Hill”), and their young son, Julius “The turnstile”); celebrations of love anticipated (“In the spring”) and love fulfilled (“Don’t ceäre”); protests against injustice and snobbery (“The love child”); struggles to accept God’s will (“Grammer a-crippled”); comic poems (“John Bloom in Lon’on”, “A lot o’ maïdens a-runnèn the vields”); and poems on numerous other subjects, with an emotional range stretching from the deepest of grief to the highest of joy. The metrical forms show astonishing versatility, from straightforward octosyllabic couplets to challenging rhyme-schemes and innovative stanzaic patterns, widely varied line-lengths, and skilful adaptations of rhetorical devices from other languages. -

Lntroduction

BerndKortmann and Kerstin Lunkenheimer lntroduction 1 Backgroundand history of this atlas This atlas offers a large-scaletypological survey of morphoslmtactic variation in the Anglophone world, basedon the analysisof 3OLl and 18indigenized L2varieties of English as well 25 English-basedpidgins and creolesfrom eight different world regions (Africa, Australia, the British Isles, the Caribbean,North America, the Pacific, South and SoutheastAsia and, as the borderline caseof an Anglophone world region, the South Atlantic). It is the outgrowth of a major electronic databaseand open accessresearch tool edited by the present editors in 2Oll (The electronicWord Atlas of Varietiesof English,short: eWAVEThttp://www.ewave- atlas.org/) and is a direct, but far more comprehensivefollow-up of the interactive CD-ROMaccompanying the Mouton de GruyterHandbook of Varietiesof English(Kortmann et al. 2oo4), Whereasthe grammar part of the latter survey was based on 75 morphoslmtacticfeatures in 46 varieties of English and English-based pidgins and creoles worldwide, its successor,the WAVEdatabase (WAVE short for: World Atlas of Vaiation in English),holds information on 235morphosyntactic features in74 datasets, i.e. about five times as much de- tail and information. The idea underlying the design of WAVEwas to createa considerablylarger and more @ fine-graineddatabase and researchtool than back in 20O4,especially one that is less Ll-centred. As a proper atlas should, WAVEis intended to survey and map the morphosyntacticvariation spacein the Anglophone world and to help us explore how much of this variation spaceis made use of in different (clustersof) varieties of English, and to what extent it is possibleto correlatethe structural profiles for indi- vidual and goups of varietieswith, for example, geography,socio-history or generalprocesses of language change,language acquisition and languagecontact. -

Pidgins and Creoles

Chapter 7: Contact Languages I: Pidgins and Creoles `The Negroes who established themselves on the Djuka Creek two centuries ago found Trio Indians living on the Tapanahoni. They maintained continuing re- lations with them....The trade dialect shows clear traces of these circumstances. It consists almost entirely of words borrowed from Trio or from Negro English' (Verslag der Toemoekhoemak-expeditie, by C.H. De Goeje, 1908). `The Nez Perces used two distinct languages, the proper and the Jargon, which differ so much that, knowing one, a stranger could not understand the other. The Jargon is the slave language, originating with the prisoners of war, who are captured in battle from the various neighboring tribes and who were made slaves; their different languages, mixing with that of their masters, formed a jargon....The Jargon in this tribe was used in conversing with the servants and the court language on all other occasions' (Ka-Mi-Akin: Last Hero of the Yakimas, 2nd edn., by A.J. Splawn, 1944, p. 490). The Delaware Indians `rather design to conceal their language from us than to properly communicate it, except in things which happen in daily trade; saying that it is sufficient for us to understand them in that; and then they speak only half sentences, shortened words...; and all things which have only a rude resemblance to each other, they frequently call by the same name' (Narratives of New Netherland 1609-1664, by J. Franklin Jameson, 1909, p. 128, quoting a comment made by the Dutch missionary Jonas Micha¨eliusin August 1628). The list of language contact typologies at the beginning of Chapter 4 had three entries under the heading `extreme language mixture': pidgins, creoles, and bilingual mixed lan- guages.