4 18Kp3zelz3 202011180343

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CINCINNATI MYTH by Eliana Johnson Saturday Night Massacre, and IRS Discrimination Wasn’T Just the Work of Rogue Agents

2013_07_01 subscribe:cover61404-postal.qxd 6/11/2013 8:18 PM Page 1 July 1, 2013 $4.99 JAY NORDLINGER: The Left’s Racial Putdowns KEVIN D. WILLIAMSON ON RAND AND STEINBECK JOHN J. MILLER HENRY OLSEN: IS RAND PAUL THE ANSWER? ON HARRY JAFFA Daniiel Foster w eliiaannaa Johnson w roobb lloonngg $4.99 tthhee eeDDittoorss 26 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base:milliken-mar 22.qxd 6/10/2013 2:27 PM Page 1 TOC:QXP-1127940144.qxp 6/12/2013 2:33 PM Page 1 Contents JULY 1, 2013 | VOLUME LXV, NO. 12 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 16 The Cincinnati Myth John J. Miller on Harry V. Jaffa p. 32 Two Cincinnati employees have told the House Oversight Committee that BOOKS, ARTS they were taking orders from Washington. One of those employees told & MANNERS the committee he began singling out tea- 41 LINCOLN’S PATH, STILL Jay Winik reviews Lincoln party applications at the request of a Unbound: How an Ambitious supervisor who told him “Washington, Young Railsplitter Saved the American Dream—And D.C., wanted some cases.” Eliana Johnson How We Can Do It Again, by Rich Lowry. COVER: ROMAN GENN 42 GREATNESS IN A DARK TIME ARTICLES Charles J. Cooper reviews Saving Justice: Watergate, the 16 THE CINCINNATI MYTH by Eliana Johnson Saturday Night Massacre, and IRS discrimination wasn’t just the work of rogue agents. Other Adventures of a Solicitor General, by Robert H. Bork. 18 ONE-PARTY TAXMEN by Daniel Foster Is it time to un-reform the civil service? 45 EPIC OF A NATION Daniel Johnson reviews Flight of 21 BUREAUCRATIC ROT by Rob Long the Eagle: The Grand Strategies A government, like a fish, decays from its guts. -

Optimal Storage Conditions for Fresh Farmed Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus) Fillets

Optimal storage conditions for fresh farmed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fillets By: CYPRIAN OGOMBE ODOLI Supervisors: Sigurjón Arason and Emilía Martinsdóttir MS committee: Hannes Magnússon, Hélène L. Lauzon and Kolbrún Sveinsdóttir Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTERS IN SCIENCE (60 ECTS units) Department of Food Science and Nutrition University of Iceland May 2009 Optimal storage conditions for fresh farmed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fillets Cyprian Ogombe Odoli Supervisors: Sigurjón Arason and Emilía Martinsdóttir MS committee: Hannes Magnússon, Hélène L. Lauzon and Kolbrún Sveinsdóttir Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTERS IN SCIENCE (60 ECTS units) Department of Food Science and Nutrition Faculty of Science University of Iceland May 2009 Declaration I wish to declare that this work has sole been done by me and has never been submitted at any other university before. ___________________ Cyprian Ogombe Odoli Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my daughter Sharon for growing up at early age without seeing her father. More so, my beloved wife Lillian Awuor for accepting a lonesome life while I pursuit academic accomplishment. ii Abstract The main aim was to establish optimal storage conditions for fresh tilapia fillets, by determining its shelf life from the sensory and microbiological evaluation, as well as monitoring its physical-chemical properties. With this intent, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) farmed in recirculation aquaculture system was filleted and packaged in 100% air and 50% CO2: 50% N2 MA prior to storage at different temperature; 1˚C and -1˚C. Initial samples from filleting (control d0) were also evaluated for comparison. -

Cold Chain in Seafood Industry

COLD CHAIN IN SEAFOOD INDUSTRY Alex Augusto Gonçalves1, Ph.D and Francisco Blaha2, MSc. Abstract: When seafood is freshly caught eating quality is high, but over time quality will deteriorate and eventually will become unsuitable for consumption. Maintenance of the cold chain and careful handling are a fundamental part in minimizing seafood spoilage. The cold chain in seafood industry is a temperature chain and begins once the seafood is caught. From the quality and regulatory perspective fresh seafood means that has been stored at 0°C and for frozen seafood it means –18°C or colder (from the sea to the consumer). The cold chain is broken every time the temperature of the seafood rises above 1°C. Fluctuations in the cold chain increases quality loss, these losses cannot be reversed by any means after the event. There are many avoidable and unavoidable occurrences that cause fluctuation in the cold chain. Good chilling and/or freezing practices on board harvest vessels are a condition sine qua non for maximizing the best possible quality of all seafoods. Best practices on seafood handling and the minimization of temperature fluctuations are paramount for seafood distributed under refrigeration (i.e., chilled and/or frozen) to maintain its quality and maximize its shelf–life. The present chapter addresses some of the developments in seafood cold chain under four mainly headings: i) cold chain in seafood industry; ii) selected aspects of refrigeration (chilling and freezing) process (including equipment and storage conditions); iii) safety and shelf–life issues in seafood cold chain; iv) regulation and legislation. 1. -

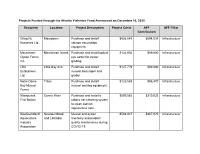

Projects Funded Through the Atlantic Fisheries Fund Announced on December 16, 2020

Projects Funded through the Atlantic Fisheries Fund Announced on December 16, 2020 Recipient Location Project Description Project Costs AFF AFF Pillar Contribution Grieg NL Marystown Purchase and install $926,045 $694,534 Infrastructure Nurseries Ltd. salmon vaccination equipment. Merasheen Merasheen Island Purchase and install optical $124,930 $99,900 Infrastructure Oyster Farms eye sorter for oyster Inc. grading. LBA Little Bay Arm Purchase and install $127,779 $99,900 Infrastructure Enterprises mussel declumper and Ltd. grader. Notre Dame Triton Purchase and install $120,588 $96,470 Infrastructure Bay Mussel mussel socking equipment. Farms Miawpukek Conne River Purchase and install a $899,583 $319,623 Infrastructure First Nation robotic net cleaning system to clean salmon aquaculture nets. Newfoundland Newfoundland Mussel and oyster $583,837 $467,070 Infrastructure Aquaculture and Labrador inventory and product Industry quality maintenance during Association COVID-19. Newfoundland Milltown Purchase of robotic net $1,752,339 $1,261,754 Infrastructure Aqua Service cleaning systems Ltd. for aquaculture pens. Bobby Noble Lewisporte Purchase and install $250,771 $99,882 Infrastructure automated longline system CRS Fishing Grates Cove Purchase and install $136,960 $99,900 Infrastructure Enterprises automated longline system Ltd. Challenger 92 Fogo Island Purchase and install $102,584 $82,067 Infrastructure Ltd. automated longline system Reginald Baine Harbour Purchase and install $9,786 $7,829 Infrastructure Keating automated jiggers and insulated boxes. Jerome Ward South East Bight Purchase and install $4,896 $3,917 Infrastructure automated jiggers and insulated boxes. Matthew Pasadena Purchase and install $21,891 $17,513 Infrastructure Rumbolt automated jiggers. Mervin Hollett Arnold's Cove Purchase and install $17,991 $12,515 Infrastructure automated jiggers and insulated boxes. -

Design and Fabrication of Slurry Ice Generator

International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM) ISSN : 2454-9150 Vol-03, Issue-07, Oct 2017 Design and Fabrication of Slurry Ice Generator Vikas K Tawde Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vidyavardhini’s College of Engineering and Technology, Vasai, Mumbai, India. Abstract: This paper proposes the Design and Fabrication of a slurry ice generator which produces slurry ice, a mixture of water and ice wherein the ice is in the form of spherical crystals of about 0.1 to 1mm in diameter. It provides 3 to 4 times better cooling compared to flaked ice owing to larger heat transfer area. Slurry ice finds application in food preservation especially in the fishing industry. In India, flaked ice is used for seafood preservation. Introduction of slurry ice in the fishing industry will result in better quality of produce. This paper is focused on the design calculations and the selection of proper components wherein the conventional ice scraper is replaced by an Archimedes’ screw to eliminate the use of circulation pump. The refrigeration system works on a simple vapor compression cycle. Ice crystals are formed on the inner surface of shell and coil type evaporator, and, scraped by the Archimedes’ screw. Keywords — Ice Slurry, Archimedes’ screw, Newtonian, pumpability, R134a, isentropic, coefficient of performance. and heat exchangers. Ice slurries can also be pumped through NTRODUCTION I. I veins and lungs to lower temperature much faster. Because of The fishing industry in India makes use of flaked ice for Pumpability slurry ice with nozzles can be used in fire preservation. Often times the quality of product received by extinguishing applications. -

A Revolution in Food Preservation Why Flake Ice Doesn’T Work Anymore…

A REVOLUTION IN FOOD PRESERVATION WHY FLAKE ICE DOESN’T WORK ANYMORE… Modern consumers have become extremely aware of how important food quality is to their nutrition and way of living. Therefore, they continue to demand food that is fresh, of higher quality, and delivered quickly to the market. This puts seafood harvesters, aquaculture producers and processors in a position where they need to adapt, but don’t have the right means to preserve harvest for long periods of time. Although it is the cheapest option, flake ice cannot do the job anymore as it: • damages the product surface and causes breakage • leads to shrinkage and weight loss The increasing demand • and creates an environment for bacteria to cause for better and fresher food quicker product spoilage. puts an even stronger pressure on aquaculture All that decreases the product value and minimizes the producers and food profit margins aquaculture manufacturers and food processors. processors need to scale in the long run. …AND SLURRY ICE DOESN’T SOLVE THE PROBLEM EITHER Liquid ice solutions, like slurry ice, use small ice crystals to absorb heat from fresh products. Usually, they have good flow properties and are easily distributed. As slurry ice creates a uniform contact with the product surface, it’s often considered an improvement over flake ice. However, this is only partial. Slurry ice still lacks the deepest level of cooling transfer to products, which may lead to spoilage. Sometimes, this results in seafood harvesters, aquaculture producers and processors to use additives in the preservation process, which is the opposite of the consumer demand for more organic, preservatives-free products. -

Guidelines for Precooling of Fresh Fish During Processing and Choice of Packaging with Respect to Temperature Control in Cold Chains

Guidelines for precooling of fresh fish during processing and choice of packaging with respect to temperature control in cold chains Kristín Líf Valtýsdóttir Björn Margeirsson Sigurjón Arason Hélène L. Lauzon Emilía Martinsdóttir Vinnsla, virðisauki og eldi Skýrsla Matís 40-10 Desember 2010 ISSN 1670-7192 Guidelines for precooling of fresh fish during processing and choice of packaging with respect to temperature control in cold chains Kristín Líf Valtýsdóttir, Björn Margeirsson, Sigurjón Arason, Hélène L. Lauzon, Emilía Martinsdóttir Titill / Title Guidelines for precooling of fresh fish during processing and choice of packaging with respect to temperature control in cold chains Höfundar / Authors Kristín Líf Valtýsdóttir, Björn Margeirsson, Sigurjón Arason, Hélène L. Lauzon, Emilía Martinsdóttir Skýrsla / Report no. 40-10 Útgáfudagur / Date: Dec 2010 Verknr. / project no. 1852/1682 Styrktaraðilar / funding: AVS Fund of Ministry of Fisheries in Iceland (R-037 08), Technology Development Fund at the Icelandic Centre for Research (081304508), University of Iceland Research Fund and EU (contract FP6-016333-2) Ágrip á íslensku: Tilgangur leiðbeininganna er að aðstoða við val á milli mismunandi aðferða við forkælingu ferskra fiskafurða ásamt því að aðstoða við val á pakkningum með tilliti til hitaálags sem varan verður fyrir á leið sinni frá framleiðanda til kaupanda. Fjallað er um eftirfarandi forkælingaraðferðir: vökvakælingu, krapaískælingu og roðkælingu (CBC, snerti- og blásturskælingu). Einnig er fjallað um meðferð afurða á meðan vinnslu stendur og áhrif mismunandi kælimiðla á hitastýringu, gæði og geymsluþol flaka áður en vörunni er pakkað. Leiðbeiningarnar taka mið af vinnslu á mögrum hvítfiski, s.s. þorski og ýsu. Niðurstöður rannsókna sýna að vel útfærð forkæling fyrir pökkun getur skilað 3 – 5 dögum lengra geymsluþoli m.v. -

Libro V FIRMA.Indb

FORO IBEROAMERICANO DE LOS RECURSOS EDITORES MARINOS Y LA Salvador Cárdenas Rojas ACUICULTURA Juan Miguel Mancera Romero Cádiz, España, 26-29 de noviembre de 2012 Manuel Rey Méndez V César Lodeiros Seijo Un mar de recursos ORGANIZAN puente entre las dos orillas Libro de Actas Sociedad Española de Acuicultura MARINOS Y LA ACUICULTURA PATROCINAN V FORO IBEROAMERICANO DE LOS RECURSOS RECURSOS DE LOS IBEROAMERICANO V FORO COLABORAN CÁDIZ 2012 “Promover y fomentar toda especie de industria y remover los obstáculos que la entorpezcan“ ( Art. 131, 21. Constitución de Cádiz de 1812) Libro de Actas Libro www.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/ifapa/firma2012 V Foro Iberoamericano de los Recursos Marinos y la Acuicultura Este libro debe ser citado de la siguiente manera: Todo el libro: Cárdenas S., Mancera J.M., Rey-Méndez M. y Lodeiros C. 2013. V Foro Iberoamericano de los Recursos Marinos y de Acuicultura. 742 pp. Edit. Asociación Cultural Foro dos Recursos Mariños e da Acuicultura das Rías Galegas, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, España. Para un trabajo en especial (ejemplo): Ruiz-Ríos, Leoncio. Estado de la acuicultura dulceacuícola en Perú. V Foro Iberoam. Rec. Mar. Acui. Cárdenas S., Mancera J.M., Rey-Méndez M., Lodeiros C. (eds.): 95-105. Imprenta: Martínez Encuadernaciones, A.G., S.L., Puerto Real, Cádiz, España. Maquetación: Rosa Mª Martín y Belén Rodríguez Depósito Legal: CA 397-2013 ISBN: 978-84-695-9072-0 2 V Foro Iberoamericano de los Recursos Marinos y la Acuicultura PRESENTACIÓN El crecimiento de la población mundial, con una proyección de 8,3 mil millones de personas para el 2030, preocupa altamente por la incapacidad de proveerles alimentos. -

Slurry Ice Machine Design Production Capacity of 1.3 Tons

International Journal of Applied Engineering Research ISSN 0973-4562 Volume 15, Number 3 (2020) pp. 212-215 © Research India Publications. http://www.ripublication.com Slurry Ice Machine Design Production Capacity of 1.3 Tons Dendi Haris1*, Nasirin1, Dahmir Dahlan2, Gunadi Zaenal Abidin1, Catur Ery Partono1, Agus Budihadi3 1 Fishing Machine, Faculty of Utilization Fisheries Resources, Jakarta Fisheries University, Jakarta, Indonesia. 2 Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Pancasila University, Jakarta, Indonesia. 3 Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Gunadarma University, Jakarta, Indonesia. Corresponding author : [email protected] Abstract There is a lot of salt in sea water, the raw material is very abundant and very cheap compared to fresh water which is used Handling of fresh fish after harvest, in fish landing sites and as the main raw material for making ice blocks. Sea water is fish processing units still uses conventional methods, so there also not disturbed by the dry season as in fresh water, when the are still many shortcomings and weaknesses that have an dry season is very difficult to find and the price is also much impact on the quality of the fish that is stored. The purpose of more expensive. this study is to produce a slurry ice machine design with an evaporator temperature reaching -5°C, a production capacity of In slurry ice as a fish cooler there is no air between the fish and 1.3 tons according to the standard and put forward an ice, so that the cooling of the fish becomes faster because of ergonomic, safety factor as well. The results showed that the direct contact with the surface and cavities in the fish is larger target temperature of the slurry ice machine evaporator reached and slower bacterial growth makes an extension of the -5°C was reached, with a temperature achievement of -5.8°C freshness of the fish. -

Chapter 10 Priority Programs and Projects

The Project for Community-based Sustainable Development Master Plan of Qeshm Island toward “Eco-Island” Final Report CHAPTER 10 PRIORITY PROGRAMS AND PROJECTS 10.1 Selection of Priority Programs and Projects 10.1.1 Establishment of evaluation criteria The projects and programs are proposed in the sector development plan of the ECO-QESHM Master Plan. Among these projects and programs is a set of priority projects, which have been selected by scoring the candidate projects in relation to the evaluation criteria. The candidate projects are the projects and programs that should be commenced in the short term until 2021. They will be preferably completed in the short term, but timing of their completion can be expanded to the medium term until 2026 and the long term until 2036. The evaluation standard is established to reflect the development objectives proposed in the ECO- QESHM Master Plan. The development objectives include four aspects, namely, the economy, the environment, society and human resources. The evaluation standard also includes urgency as shown in Table 2.1.1. Evaluation criteria are constructed as broadly as possible for each evaluation standard. The objectives of establishing the criteria this broadly are to avoid missing out on important requirements for the priority projects. Even though the criteria overlap with different evaluation standards, the overlapped criteria are considered to be representative of the significance of such criteria in order to achieve the vision behind the eco-island development. The evaluation criteria for economic enhancement constitute the creation of job opportunities, livelihood improvement and regional economic growth. The promotion of export products, logistics and direct investment are also included in order to meet the role of the free zone (FZ) on Qeshm Island in terms of economic enhancement standards. -

Funding and Achievements During 2003-2012

SEAFDEC Special Council Meeting WP03 3-4 October 2013, Bangkok, Thailand REVIEWS SEAFDEC Programs: Funding and Achievements during 2003-2012 SOUTHEAST ASIAN FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT CENTER Secretariat 28 August 2013 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SEAFDEC Programs: Funding and Achievements 2003-2012 During the period from 2003-2012, SEAFDEC implemented 84 projects using total SEAFDEC funds of 47,433,377 US$, most of which or about 37% was utilized for research while 19% was used for training, 16% for technology development, 12% for information, 9% for policy development, and 7% for other activities (Table 1). The Aquaculture Department (AQD) used a significant 63% of the total funds followed by the Secretariat at 16% and the Training Department (TD) at 12%, while the Marine Fishery Resources Development and Management Department (MFRDMD) and Marine Fisheries Research Department (MFRD) used the remaining 5% and 4%, respectively. The countries hosting the Departments contributed a major portion of the total funds at 47% while the Japanese Trust Fund contributed about 24%, with the total external funds contributed about 8%, Sida funds and internally generated funds at 6% each, other Japan funds at 5%, and MRC and the ASEAN Foundation at 2% each (Table 2, Figure 1). As the host of AQD, Philippines allocated during the said period a total of 21,003,590 US$ that represented about 71% of the total funds available at AQD, the remaining 29% of which was provided by external funds at 11%, internally-generated funds at 9%, Japanese Trust Fund at 7%, and other Japan Fund at 2%. Of the total funds used by AQD, 52% was spent for research, 23% for technology development and improvement, 10% for training and capacity building, 7% for information activities, 4% for policy development, and another 4% for other expenditures including administrative costs. -

Regional Conference on Food Security and Income Generation Through The

FAO ISSN 2070-6103 43 FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE PROCEEDINGS 43 FAO FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE PROCEEDINGS 43 of losses and waste in fisheries the reduction on food security and income generation through Regional Conference Regional Conference on food security and income generation through the reduction of losses Regional Conference on food and waste in fisheries security and income generation Nouakchott, Mauritania, 15–17 December 2013 through the reduction of losses The Regional Conference on food security and income generation through reduction of losses and waste in fisheries and waste in fisheries was held from 15 to 17 December 2013 at the Wissal Hotel, Nouakchott, Islamic Republic of Mauritania. It was jointly convened by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the Center for Marketing Information Nouakchott, Mauritania, and Advisory Services for Fishery Products in the Arab Region 15–17 December 2013 (InfoSamak) and the Ministry for Fisheries and Maritime Economy. The 78 participants included representatives from 14 countries, civil society organizations, fishers’ associations and research institutes. The objectives were to: i) review current fisheries practices in the Near East and North Africa region; ii) examine case studies of best practices to identify suitable options for the region; and iii) identify policy-level and operational-level interventions to improve food security and income generation by reducing losses and waste. The conference identified various tools and practices that would reduce fishery losses and waste through the generation of accurate baseline data and loss-reduction initiatives. Case studies of best practices in five countries were considered, after which group discussions focused on: i) best practices for minimizing post-harvest losses and waste; ii) improved utilization of fishery by-products to minimize waste; iii) approaches based on value chains for minimizing fishery losses and waste; and iv) best practices for managing fish bycatches and discards.