Gabriele D'annunzio's Coup in Rijeka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

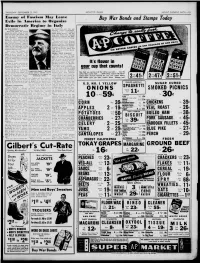

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message After the Oath*

Appendix: Einaudi, President of the Italian Republic (1948–1955) Message after the Oath* At the general assembly of the House of Deputies and the Senate of the Republic, on Wednesday, 12 March 1946, the President of the Republic read the following message: Gentlemen: Right Honourable Senators and Deputies! The oath I have just sworn, whereby I undertake to devote myself, during the years awarded to my office by the Constitution, to the exclusive service of our common homeland, has a meaning that goes beyond the bare words of its solemn form. Before me I have the shining example of the illustrious man who was the first to hold, with great wisdom, full devotion and scrupulous impartiality, the supreme office of head of the nascent Italian Republic. To Enrico De Nicola goes the grateful appreciation of the whole of the people of Italy, the devoted memory of all those who had the good fortune to witness and admire the construction day by day of the edifice of rules and traditions without which no constitution is destined to endure. He who succeeds him made repeated use, prior to 2 June 1946, of his right, springing from the tradition that moulded his sentiment, rooted in ancient local patterns, to an opinion on the choice of the best regime to confer on Italy. But, in accordance with the promise he had made to himself and his electors, he then gave the new republican regime something more than a mere endorsement. The transition that took place on 2 June from the previ- ous to the present institutional form of the state was a source of wonder and marvel, not only by virtue of the peaceful and law-abiding manner in which it came about, but also because it offered the world a demonstration that our country had grown to maturity and was now ready for democracy: and if democracy means anything at all, it is debate, it is struggle, even ardent or * Message read on 12 March 1948 and republished in the Scrittoio del Presidente (1948–1955), Giulio Einaudi (ed.), 1956. -

Foreign News: Where Is Signor X?

Da “Time”, 24 maggio 1943 Foreign News: Where is Signor X? Almost 21 years of Fascism has taught Benito Mussolini to be shrewd as well as ruthless. Last week he toughened the will of his people to fight, by appeals to their patriotism, and by propaganda which made the most of their fierce resentment of British and U.S. bombings. He also sought to reduce the small number pf Italians who might try to cut his throat by independent deals with the Allies. The military conquest of Italy may be no easy task. After the Duce finished his week's activities, political warfare against Italy looked just as difficult, and it was hard to find an alternative to Mussolini for peace or postwar negotiations. No Dorlans. The Duce began by ticking off King Vittorio Emanuele, presumably as insurance against the unlikely prospect that the sour-faced little monarch decides either to abdicate or convert his House of Savoy into a bargain basement for peace terms. Mussolini pointedly recalled a decree of May 10, 1936, which elevated him to rank jointly with the King as "first marshal of Italy." Thus the King (constitutionally Commander in Chief of all armed forces) can legally make overtures to the Allies only with the consent and participation of the Duce. Italy has six other marshals. Mussolini last week recalled five of them to active service.* Most of these men had been disgraced previously to cover up Italian defeats. Some of them have the backing of financial and industrial groups which might desert Mussolini if they could make a better deal. -

JENS PETERSEN the Italian Aristocracy, the Savoy Monarchy, and Fascism

JENS PETERSEN The Italian Aristocracy, the Savoy Monarchy, and Fascism in KARINA URBACH (ed.), European Aristocracies and the Radical Right 1918-1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 91–110 ISBN: 978 0 199 23173 7 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 6 The Italian Aristocracy, the Savoy Monarchy, and Fascism JENS PETERSEN What political role did the aristocracy play in the early decades of a unified Italy? Researchers are widely divided in their opin- ions on this question. They range from the rose-tinted view of Arno Mayer, who regarded the ancien regi,me nobility as still at the core of Italy's social and political system, to opinions that speak of a rapid and unstoppable decline. 1 Although aristocratic values continued to shape the path of upward mobility for the middle classes, nobility as such did not play an important role in the Italian nineteenth-century social structure, because it did not constitute a well-defined group in itself, due to its regional more than national status. -

Questionariostoria

QuestionarioStoria 1 In seguito a quale evento bellico l'esercito del Regno 7 A seguito di quale accusa fu sciolto il Partito d'Italia poté entrare in Roma nel 1870? Socialista Italiano nel 1894? A) Alla sconfitta dei Francesi a Sedan A) L'accusa di aver appoggiato i Fasci siciliani B) Alla sconfitta dei Prussiani a Verdun B) L'accusa di spionaggio a favore della Seconda Internazionale socialista C) Alla sconfitta degli Austriaci a Sadowa C) L'accusa di voler attentare alla vita del sovrano D) Alla sconfitta dei Francesi a Lipsia D) L' accusa di aver attentato alla vita di Umberto I 2 Come reagì il governo Rudinì alle agitazioni popolari del 1898? 8 Tra quali nazioni l'irredentismo italiano fu causa di rapporti diplomatici tesi? A) Cercò alleanze in parlamento A) L'Italia e la Polonia B) Fece importanti concessioni ai dimostranti B) L'Italia e la Grecia C) Rassegnò le dimissioni C) L'Italia e l'Impero ottomano D) Si affidò all'esercito D) L'Italia e l'Austria - Ungheria 3 Nel 1884 il governo Depretis abolì un'imposta invisa alla popolazione. Quale? 9 In quale anno morì Camillo Cavour? A) La tassa sul macinato A) Nel 1865 B) La tassa doganale regionale B) Nel 1875 C) La tassa comunale di utilizzo delle acque pubbliche C) Nel 1861 D) La tassa sulla prima casa D) Nel 1871 4 Quali direttive di politica estera adottò Antonio 10 Nel 1861 espugnò, dopo un assedio, la fortezza di Rudinì nel marzo del 1896, quando fu incaricato di Gaeta, ultima roccaforte dei Borbone; condusse nella sostituire Francesco Crispi alla guida dell'Esecutivo? Terza guerra d'indipendenza le truppe dell'esercito che operavano sul basso Po. -

Fra Tittoni E Sonnino. Francesco Tommasini, La Diplomazia Italiana E La Nuova Polonia

CAPITOLO SECONDO FRA TITTONI E SONNINO. FRANCESCO TOMMASINI, LA DIPLOMAZIA ITALIANA E LA NUOVA POLONIA irmato il trattato di pace con la Germania alla fine del giugno 1919, l’Italia decise di normalizzare i rapporti diplomatici con la Polonia e di costituire a Varsavia con una vera e propria Legazione. Dopo un periodo di transizione caratterizzato dalla Fpresenza a Varsavia di un semplice incaricato d’affari, Alessandro Cam- pana de Brichanteau, nel settembre 1919 il governo di Roma, da fine giugno presieduto da Francesco Saverio Nitti e con ministro degli Esteri Tommaso Tittoni, nominò rappresentante diplomatico italiano in Polonia Francesco Tommasini, già capo di Gabinetto di Tittoni1. Francesco Tommasini era nato a Roma il 12 settembre 18752, figlio di Oreste Tommasini e di Zenaide Nardini. I Tommasini erano una 1] Al riguardo: S. RUGGERI, Introduzione a Inventario Ambasciata d’Italia in Varsavia (1945-1971), “Storia e Diplomazia. Rassegna dell’Archivio storico del Ministero degli Affari Esteri”, 2014, n. 1-2, p. 143-152, in particolare pp. 145-146. 2] Alcune informazioni sulla vita e sulla carriera di Francesco Tommasini sono conservate nel suo fascicolo personale presso l’Archivio storico del Ministero degli Affari Esteri: ASMAE, Archivio del personale, Serie VII, Diplomatici e consoli, posizione T 5, fascicolo personale Francesco CONFERENZE 138 Tommasini. Utile pure: La formazione della diplomazia nazionale (1861-1915). Repertorio 23 CAPITOLO SECONDO famiglia di possidenti, molto agiata e in vista a Roma. La loro resi- denza romana era il grande Palazzo Tommasini in via Nazionale 89. Dopo l’annessione del Lazio all’Italia e il trasferimento della capitale del Regno a Roma, i Tommasini divennero parte integrante dei gruppi dominanti del liberalismo conservatore capitolino, espressione di quelle componenti dei ceti borghesi locali, spesso composti da mercanti di campagna che avevano militato nel movimento risorgimentale e dai loro figli: i Tittoni, i Silvestrelli, gli Amadei, i De Angelis3. -

APPENDICE I - ' ' ' -Il

vi APPENDICE I - ' ' ' -il PRESIDENTI DELLA REPUBBLICA ENRICO DE NICOLA, Capo prov visorio dello Stato dal 28 giugno 1946 al 24 giugno 1947 dal 25 giugno al 31 dicembre 1947 ENRICO DE NICOLA, Presidente della Repubblica ; dal 1° gennaio 1948 all'11 maggio 1948 LUIGI EINAUDI, Presidente della Repubblica dall'll maggio 1948 >"..". r ?.-.' V-r^v;*-"^"^ - •«• « ***•••>*• , . :ir.'-.•.:••.• L T • ~ i : ~ . ..' -» "• »-1 -?. ' *- / >^1 • - A •; li ENRICO DE NICOLA 82. • ' ? LUIGI EINAUDI PRESIDENTE DELLA CAMERA DEI DEPUTATI GIOVANNI GRONCHI. dall'8 maggio 1948 PRESIDÈNTE DEL SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA IVANOE BONOMI dall'8 maggio 1948 GIOVANNI GRONCHI -J-Ì IVANOE BONOMI PRESIDENTI DELLA CAMERA DEI DEPUTATI DALLA I ALLA XXVI LEGISLATURA VINCENZO GIOBERTI dall'8 maggio al 20 luglio 1848 e dal 16 ott. 30 die. 1848 IL . LORENZO PARETO dal 1° febbr. al 30 marzo 1849 III. LORENZO PARETO dal 30 luglio al 20* nov. 1849 IV . PIER DIONIGI PINELLI dal 20 die. 1849 al 25 aprile 1852 UHBANO RATTAZZI dall'll maggio 1852 al 27 ott. 1853 CARLO BON-COMPAGNI dal 16 al 21 nov. 1853 V ... CARLO BON-COMPAGNI. dal 19 die. 1853 al 16 giugno 1856 CARLO CADORNA.. dal 7 genn. al 16 luglio 1857 VI .. CARLO CADORNA. dal 14 die. 1857 al 14 luglio 1858 URBANO RATTAZZI. dal 10 genn. 1859 al 21 genn. 1860 VII . GIOVANNI LANZA dal 2 aprile al 28 die. 1860 VIII URBANO RATTAZZI. dal 18 febbr. 1861 al 2 marzo 1862 SEBASTIANO TECCHIO dal 22 marzo 1862 al 21 magg. 1863 GIOVANNI BATTISTA CASSINIS dal 25 maggio 1863 al 7 sett. 1865 IX. -

Tracing the Treaties of the EU (March 2012)

A Union of law: from Paris to Lisbon — Tracing the treaties of the EU (March 2012) Caption: This brochure, produced by the General Secretariat of the Council and published in March 2012, looks back at the history of European integration through the treaties, from the Treaty of Paris to the Treaty of Lisbon. Source: General Secretariat of the Council. A Union of law: from Paris to Lisbon – Tracing the treaties of the European Union. Publications Offi ce of the European Union. Luxembourg: March 2012. 55 p. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/librairie/PDF/QC3111407ENC.pdf. Copyright: (c) European Union, 1995-2013 URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/a_union_of_law_from_paris_to_lisbon_tracing_the_treaties_of_the_eu_march_2012-en- 45502554-e5ee-4b34-9043-d52811d422ed.html Publication date: 18/12/2013 1 / 61 18/12/2013 CONSILIUM EN A Union of law: from Paris to Lisbon Tracing the treaties of the European Union GENERAL SECRETARIAT COUNCIL THE OF 1951–2011: 60 YEARS A UNION OF LAW THE EUROPEAN UNION 2010011 9 December 2011 THE TREATIES OF Treaty of Accession of Croatia,ratification in progress 1 December 2009 Lisbon Treaty, 1 January 2007 THE EUROPEAN UNION Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania, Treaty establishing a Constitution29 for October Europe, 2004 signed on did not come into force Lisbon: 13 December 2007 CHRON BOJOTUJUVUJPO $PVODJMCFDPNFT Treaty of Accession of the Czech Republic, Estonia, Cyprus, Latvia, t ЅF&VSPQFBO 1 May 2004 CFUXFFOUIF&VSPQFBO Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia, t - BXNBLJOH QBSJUZ -

Carlo Sforza and Diplomatic Europe 1896-1922

Dottorato di Ricerca in Studi Politici (Scuola di dottorato Mediatrends. Storia, Politica e Società) Ciclo XXX Carlo Sforza and Diplomatic Europe 1896-1922 Tutor Co-tutor Chiar.mo Prof. Luca Micheletta Chiar.mo Prof. Massimo Bucarelli Dottoranda Viviana Bianchi matricola 1143248 All he tasted; glory growing Greater after great embroil; Flight; and victory bestowing Palace; and the sad exile; Twice in the dust a victim razed, Twice on the altar victim blazed. Alessandro Manzoni, The Fifth of May, 1821 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................................................................................... 1 Foreword .......................................................................................................... 3 1. The Inception of a Diplomatic Career ...................................................... 8 1.I. A Young Amidst “Moderates” ........................................................... 9 1.II. New Diplomats at the Trailhead ..................................................... 16 1.III. Volunteer in Cairo: Watching the Moderates’ Comeback .......... 21 1. IV. Tornielli and the Parisian Practice ................................................ 27 1.V. From Paris to Algeciras: “Classes” of Method .............................. 35 2. Shifting Alliances ...................................................................................... 44 2.I. Madrid: Cut and Run with Diplomacy ........................................... 45 2.II. A New Beginning in Constantinople ............................................ -

Origins of Fascism

><' -3::> " ORIGINS OF FASCISM by Sr. M. EVangeline Kodric, C.. S .. A. A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette Unive,r s1ty in Partial FulfillmeIlt of the Re qUirements for the Degree of Master of Arts M1lwaukee, Wisconsin January, -1953 ',j;.",:, ':~';'~ INTRODUCTI ON When Mussolini founded the Fascist Party in 1919, he " was a political parvenu who had to create his ovm ideological pedigree. For this purpose he drew upon numerous sources of the past and cleverly adapted them to the conditions actually existing in Italy during the postwar era. The aim of this paper 1s to trace the major roots of the ideology and to in terpret some of the forces that brought about the Fascistic solution to the economic and political problems as t hey ap peared on the Italian scene. These problems, however, were not peculiar to Italy alone. Rather they were problems that cut across national lines, and yet they had to be solved within national bounda ries. Consequently, the idea that Fascism is merely an ex tension of the past is not an adequate explanation for the coming of Fascism; nor is the idea that Fascism is a mo mentary episode in history a sufficient interpr etat ion of the phenomenon .. ,As Fascism came into its own , it evolved a political philosophy, a technique of government, which in tUrn became an active force in its own right. And after securing con trol of the power of the Italian nation, Fascism, driven by its inner logic, became a prime mover in insti gating a crwin of events that precipitated the second World War. -

Publisher's Note

Adam Matthew Publications is an imprint of Adam Matthew Digital Ltd, Pelham House, London Road, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2AG, ENGLAND Telephone: +44 (1672) 511921 Fax: +44 (1672) 511663 Email: [email protected] FOREIGN OFFICE FILES FOR POST-WAR EUROPE Series One: The Schuman Plan and the European Coal and Steel Community Part 1: 1950-1953 Part 2: 1954-1955 Part 3: 1956-1957 Publisher's Note “FO 371 Files are the crucial UK source for the ‘insider’s view’ at the Foreign Office over the whole Schuman Plan and ECSC scheme, providing primary data and intelligence on the early years of operation.” Dr Martin Dedman School of Economics Middlesex University Within this microfilm collection of British Foreign Office Files can be found documents that relate directly to the fundamental questions of European co-operation and integration. The foundation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in April 1951 was the first significant move towards European Union, requiring countries to forsake a degree of national sovereignty and accept a supranational authority. Proposed by French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman and drafted by Jean Monnet, head of the French Planning Commission, it made clear from the outset its federal objectives: “The pooling of coal and steel production will immediately provide for the establishment of common bases for economic development as a first step in the federation of Europe, and will change the destinies of those regions which have long been devoted to the munitions of war, of which they have been the most constant victims.” These British Foreign Office Files, taken from Public Record Office Class FO 371, contain files covering all the major issues raised by the creation of the ECSC. -

CONTINUITY and CHANGE in the ITALIAN FOREIGN POLICY UNISCI Discussion Papers, Núm

UNISCI Discussion Papers ISSN: 1696-2206 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Leonardis, Massimo de INTRODUCTION: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN THE ITALIAN FOREIGN POLICY UNISCI Discussion Papers, núm. 25, enero, 2011, pp. 9-15 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=76717367002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 INTRODUCTION: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN THE ITALIAN FOREIGN POLICY Massimo de Leonardis 1 Catholic University of the Sacred Heart Abstract: The years 1943-45 marked the fundamental turning point in the history of Italian foreign policy. The breakdown of the traditional foreign policy of the Italian state made necessary to rebuild it on new foundations in the new international context. The real rehabilitation came in 1949, when Italy was admitted to the Atlantic Alliance as a founding member, changing in a little more than two years her status from that of a defeated enemy to that of a full fledged ally. Since unification, Italian governing elites had two basic doctrines of foreign policy. During the monarchist period (both Liberal and Fascist), Italian elites fully shared the traditional concepts and practices of traditional diplomacy: power politics, the games of the alliances, defence of national interest, gunboat diplomacy, colonialism and so on. Italy seemed to be particularly cynical (boasting her «sacred egoism»), for the reason that she was a newcomer looking for room.