Download (1145Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gruppo Dei Genetisti Forensi Italiani 21° Convegno Nazionale

gruppo dei Genetisti Forensi Italiani 21° Convegno Nazionale Lipari, 5-7 settembre 2006 PRESENTAZIONE Cari Amici e Colleghi, siamo particolarmente lieti di invitarVi per il 21° Convegno GeFI che si terrà nell’isola di Lipari, presso l’Hotel “Tritone”, dal 5 al 7 settembre 2006. È un grande onore per noi della Sezione di medicina legale del Dipartimento di medicina sociale del territorio dell’Università di Messina, organizzare quest’altro incontro del Gruppo e siamo grati al Presidente, Prof. Adriano Tagliabracci ed al Consiglio di Presidenza dei Genetisti Forensi Italiani. Anche in questa occasione, come consuetudine, la scelta degli argomenti va di pari passo con l’evoluzione delle conoscenze tecnico-scientifiche, in una fase storica caratterizzata dal rapido espandersi degli ambiti di applicazione della genetica, anche nel settore forense e dall’enorme interesse della società, sempre affascinata dal potere identificativo della persona, sia per quanto attiene alla definizione dei rapporti di consanguineità, che per quanto concerne le investigazioni criminalistiche; interesse documentato, tra l’altro, dal notevolissimo successo di serie e programmi televisivi e dall’enorme espansione dei media rispetto a casi giudiziari “high profile”. Sulla base di tali premesse, quindi, è stato definito un programma convegnistico capace di raccogliere l’attualità e le prospettive dell’analisi genetica forense, anche dal punto di vista giuridico-processuale, in relazione alla verosimilmente prossima introduzione, anche in Italia, di una banca dati di DNA a fini criminalistici. Ciò rende particolarmente stimolante ed affascinante il nostro difficile compito di genetisti forensi che non può e non deve prescindere dalla più alta missione relativa alla definizione ed applicazione condivisa di regole tecnico- scientifiche atte a produrre “evidenza”, sempre più spesso comprovante - e definitivamente - realtà attributive di diritti fondamentali della persona umana. -

October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (Excepts)

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified October 22, 1962 Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts) Citation: “Amintore Fanfani Diaries (excepts),” October 22, 1962, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Italian Senate Historical Archives [the Archivio Storico del Senato della Repubblica]. Translated by Leopoldo Nuti. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/115421 Summary: The few excerpts about Cuba are a good example of the importance of the diaries: not only do they make clear Fanfani’s sense of danger and his willingness to search for a peaceful solution of the crisis, but the bits about his exchanges with Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Carlo Russo, with the Italian Ambassador in London Pietro Quaroni, or with the USSR Presidium member Frol Kozlov, help frame the Italian position during the crisis in a broader context. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Italian Contents: English Translation The Amintore Fanfani Diaries 22 October Tonight at 20:45 [US Ambassador Frederick Reinhardt] delivers me a letter in which [US President] Kennedy announces that he must act with an embargo of strategic weapons against Cuba because he is threatened by missile bases. And he sends me two of the four parts of the speech which he will deliver at midnight [Rome time; 7 pm Washington time]. I reply to the ambassador wondering whether they may be falling into a trap which will have possible repercussions in Berlin and elsewhere. Nonetheless, caught by surprise, I decide to reply formally tomorrow. I immediately called [President of the Republic Antonio] Segni in Sassari and [Foreign Minister Attilio] Piccioni in Brussels recommending prudence and peace for tomorrow’s EEC [European Economic Community] meeting. -

Atti Parlamentari Della Biblioteca "Giovarmi Spadolini" Del Senato L'8 Ottobre

SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA XVII LEGISLATURA Doc. C LXXII n. 1 RELAZI ONE SULLE ATTIVITA` SVOLTE DAGLI ENTI A CARATTERE INTERNAZIONALISTICO SOTTOPOSTI ALLA VIGILANZA DEL MINISTERO DEGLI AFFARI ESTERI (Anno 2012) (Articolo 3, quarto comma, della legge 28 dicembre 1982, n. 948) Presentata dal Ministro degli affari esteri (BONINO) Comunicata alla Presidenza il 16 settembre 2013 PAGINA BIANCA Camera dei Deputati —3— Senato della Repubblica XVII LEGISLATURA — DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI — DOCUMENTI INDICE Premessa ................................................................................... Pag. 5 1. Considerazioni d’insieme ................................................... » 6 1.1. Attività degli enti ......................................................... » 7 1.2. Collaborazione fra enti ............................................... » 10 1.3. Entità dei contributi statali ....................................... » 10 1.4. Risorse degli Enti e incidenza dei contributi ordinari statali sui bilanci ......................................................... » 11 1.5. Esercizio della funzione di vigilanza ....................... » 11 2. Contributi ............................................................................ » 13 2.1. Contributi ordinari (articolo 1) ................................. » 13 2.2. Contributi straordinari (articolo 2) .......................... » 15 2.3. Serie storica 2006-2012 dei contributi agli Enti internazionalistici beneficiari della legge n. 948 del 1982 .............................................................................. -

Archivio Centrale Dello Stato Inventario Del Fondo Ugo La Malfa Sala Studio

Archivio centrale dello Stato Inventario del fondo Ugo La Malfa Sala Studio INVENTARIO DEL FONDO UGO LA MALFA (1910 circa – 1982) a cura di Cristina Farnetti e Francesca Garello Roma 2004-2005 Il fondo Ugo La Malfa è di proprietà della Fondazione Ugo La Malfa, via S.Anna 13 – 00186 Roma www.fondazionelamalfa.org [email protected] Depositato in Archivio centrale dello Stato dal 1981 Il riordino e l’inventariazione è stato finanziato dal Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali. Direzione generale per gli archivi II INDICE GENERALE INTRODUZIONE .................................................................................................V INVENTARIO DEL FONDO ............................................................................ XI SERIE I. ATTI E CORRISPONDENZA...............................................................1 SERIE II ATTIVITÀ POLITICA .........................................................................13 SOTTOSERIE 1. APPUNTI RISERVATI 50 SERIE III. CARICHE DI GOVERNO ................................................................59 SOTTOSERIE 1. GOVERNI CON ORDINAMENTO PROVVISORIO (GOVERNO PARRI E I GOVERNO DE GASPERI) 61 SOTTOSERIE 2. MINISTRO SENZA PORTAFOGLIO (VI GOVERNO DE GASPERI) 63 SOTTOSERIE 3. MINISTRO PER IL COMMERCIO CON L'ESTERO (VI E VII GOVERNO DE GASPERI) 64 SOTTOSERIE 4. MINISTRO DEL BILANCIO (IV GOVERNO FANFANI) 73 SOTTOSERIE 5. MINISTRO DEL TESORO (IV GOVERNO RUMOR) 83 SOTTOSERIE 6. VICEPRESIDENTE DEL CONSIGLIO (IV GOVERNO MORO) 103 SOTTOSERIE 7. FORMAZIONE DEL GOVERNO E VICEPRESIDENTE -

Title Items-In-Visits of Heads of States and Foreign Ministers

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page Date 15/06/2006 Time 4:59:15PM S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Expanded Number S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Title items-in-Visits of heads of states and foreign ministers Date Created 17/03/1977 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0907-0001: Correspondence with heads-of-state 1965-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit •3 felt^ri ly^f i ent of Public Information ^ & & <3 fciiW^ § ^ %•:£ « Pres™ s Sectio^ n United Nations, New York Note Ko. <3248/Rev.3 25 September 1981 KOTE TO CORRESPONDENTS HEADS OF STATE OR GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERS TO ATTEND GENERAL ASSEMBLY SESSION The Secretariat has been officially informed so far that the Heads of State or Government of 12 countries, 10 Deputy Prime Ministers or Vice- Presidents, 124 Ministers for Foreign Affairs and five other Ministers will be present during the thirty-sixth regular session of the General Assembly. Changes, deletions and additions will be available in subsequent revisions of this release. Heads of State or Government George C, Price, Prime Minister of Belize Mary E. Charles, Prime Minister and Minister for Finance and External Affairs of Dominica Jose Napoleon Duarte, President of El Salvador Ptolemy A. Reid, Prime Minister of Guyana Daniel T. arap fcoi, President of Kenya Mcussa Traore, President of Mali Eeewcosagur Ramgoolare, Prime Minister of Haur itius Seyni Kountche, President of the Higer Aristides Royo, President of Panama Prem Tinsulancnda, Prime Minister of Thailand Walter Hadye Lini, Prime Minister and Kinister for Foreign Affairs of Vanuatu Luis Herrera Campins, President of Venezuela (more) For information media — not an official record Office of Public Information Press Section United Nations, New York Note Ho. -

ICRC President in Italy…

INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS ICRC President in Italy... The President of the ICRC, Mr. Alexandre Hay, was in Italy from 15 to 20 June for an official visit. He was accompanied by Mr. Sergio Nessi, head of the Financing Division, and Mr. Melchior Borsinger, delegate-general for Europe and North America. The purpose of the visit was to contact the Italian authorities, to give them a detailed account of the ICRC role and function and to obtain greater moral and material support from them. The first day of the visit was mainly devoted to discussions with the leaders of the National Red Cross Society and a tour of the Society's principal installations. On the same day Mr. Hay was received by the President of the Republic, Mr. Sandro Pertini. Other discussions with government officials enabled the ICRC delegation to explain all aspects of current ICRC activities throughout the world. Mr. Hay's interlocutors were Mr. Filippo Maria Pandolfi, Minister of Finance; Mr. Aldo Aniasi, Minister of Health; Mrs. Nilde Iotti, Chairman of the Chamber of Deputies; Mr. Amintore Fanfani, President of the Senate; Mr. Paulo Emilio Taviani, Chairman of the Chamber of Deputies' Foreign Affairs Commission and Mr. Giulio Andreotti, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Affairs Commission. Discussions were held also with the leaders of the Italian main political parties. On 20 June President Hay, Mr. Nessi and Mr. Borsinger were received in audience by H.H. Pope John-Paul II, after conferring with H.E. Cardinal Casaroli, the Vatican Secretary of State, and H.E. Cardinal Gantin, Chairman of the "Cor Unum" Pontifical Council and of the pontifical Justice and Peace Commission. -

News from Copenhagen

News from Copenhagen Number 418 Current Information from the OSCE PA International Secretariat 25 January 2012 President Efthymiou promotes OSCE in official visits to Italy and the Holy See President Petros Efthymiou highlighted the importance of the OSCE in Eurasian security and applauded the Holy See for promoting a framework of values within the Organization during official visits to Rome and the Vatican 23-26 January. Efthymiou, with Vice President Riccardo Migliori (Italy) and Third Committee Chair Matteo Mecacci (Italy), met with the Vatican’s Secretary for Relations with States, Archbishop Vice-President Riccardo Migliori (Italy) and President Petros Efthymiou meet with the Vatican’s Secretary Dominique Mamberti, who expressed for Relations with States, Archbishop Dominique Mamberti. appreciation for the Assembly’s adoption of resolution on the protection of Christians at the Belgrade In meetings with Italian and Vatican officials, Efthymiou Annual Session. pointed out that the field presences represent an important In Rome, Efthymiou met with Italian Minister of Defense tool for the Organization to deliver results related to Giampaolo Di Paola and Deputy Foreign Minister Staffan De conflict prevention and resolution, and institution building. Mistura. The Italian authorities congratulated the OSCE PA He underlined the importance of the OSCE Parliamentary for its major role during the Tunisian elections and the special Assembly providing more visibility and guidance to the work presentation on Nagorno-Karabakh held last fall. of the OSCE. Efthymiou also met with Speaker Gianfranco Fini of the Efthymiou delivered two lectures about the OSCE’s role in Italian Chamber of Deputies and Vice President Emma Bonino regional and global security at Sapienza Universty of Rome of the Senate, other party leaders, as well as former Foreign and Roma Tre University. -

The Schengen Agreements and Their Impact on Euro- Mediterranean Relations the Case of Italy and the Maghreb

125 The Schengen Agreements and their Impact on Euro- Mediterranean Relations The Case of Italy and the Maghreb Simone PAOLI What were the main reasons that, between the mid-1980s and the early 1990s, a group of member states of the European Community (EC) agreed to abolish internal border controls while, simultaneously, building up external border controls? Why did they act outside the framework of the EC and initially exclude the Southern members of the Community? What were the reactions of both Northern and Southern Mediter- ranean countries to these intergovernmental accords, known as the Schengen agree- ments? What was their impact on both European and Euro-Mediterranean relations? And what were the implications of the accession of Southern members of the EC to said agreements in terms of relations with third Mediterranean countries? The present article cannot, of course, give a comprehensive answer to all these complex questions. It has nonetheless the ambition of throwing a new light on the origins of the Schengen agreements. In particular, by reconstructing the five-year long process through which Italy entered the Schengen Agreement and the Conven- tion implementing the Schengen Agreement, it will contribute towards the reinter- pretation of: the motives behind the Schengen agreements; migration relations be- tween Northern and Southern members of the EC in the 1980s; and migration relations between the EC, especially its Southern members, and third Mediterranean countries in the same decade. The article is divided into three parts. The first examines the historical background of the Schengen agreements, by placing them within the context of Euro-Mediter- ranean migration relations; it, also, presents the main arguments. -

St. John's Honors Scelba, Martino of Italy

William jacobellis Mario Scelba1 premier of Italy1 kisses the ring of Bishop fames Griffiths 1 23C at the special convoccttion in honor of the Italian stcltesmen early this month in Brooklyn. St. John's Honors Scelba, Martino of Italy St. John's University held a special In 1947 he became minister of in Elected in 1946 to the Constituent convocation to a ward honorary doctor ternal affairs under Alcide de Gasperi, Assembly after laboring with the Lib of laws degrees April 2 to Mario Scel serving in seven cabinets under him eral Party (which supports Scelba' s ba, premier of Italy, and Gaetano and fostering the Scelba Law which Christian Democrats) during the Fasc Martino, Italy's foreign minister, be banned Fascism and Communism. ist era, he served as the Assembly's fore 500 guests at the Downtown During World War II he had been vice president and as vice president ·.Jf Division. arrested by the Germans, but reentered the Chamber of Deputies. Columbia and Fordham Universities public life as one of the five directors Last year he was named minister of similarly honored the two visiting Ital of the new post-war Christian Demo education and only a few months ago ian statesmen who have since returned crat Party. became minister of foreign affairs. to their native country. Since the beginning of 1954, he has Very Rev. John A. Flynn, C.M., ex been premier of Italy, gaining nine tended the University's greetings at Scelba (pronounced Shell-ba), often votes of confidence. Premier Scelba is the Convocation, and Rev. -

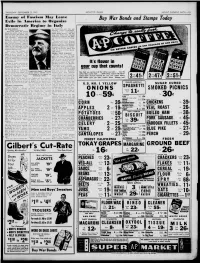

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

Governo Berlusconi Iv Ministri E Sottosegretari Di

GOVERNO BERLUSCONI IV MINISTRI E SOTTOSEGRETARI DI STATO MINISTRI CON PORTAFOGLIO Franco Frattini, ministero degli Affari Esteri Roberto Maroni, ministero dell’Interno Angelino Alfano, ministero della Giustizia Giulio Tremonti, ministero dell’Economia e Finanze Claudio Scajola, ministero dello Sviluppo Economico Mariastella Gelmini, ministero dell’Istruzione Università e Ricerca Maurizio Sacconi, ministero del Lavoro, Salute e Politiche sociali Ignazio La Russa, ministero della Difesa; Luca Zaia, ministero delle Politiche Agricole, e Forestali Stefania Prestigiacomo, ministero dell’Ambiente, Tutela Territorio e Mare Altero Matteoli, ministero delle Infrastrutture e Trasporti Sandro Bondi, ministero dei Beni e Attività Culturali MINISTRI SENZA PORTAFOGLIO Raffaele Fitto, ministro per i Rapporti con le Regioni Gianfranco Rotondi, ministro per l’Attuazione del Programma Renato Brunetta, ministro per la Pubblica amministrazione e l'Innovazione Mara Carfagna, ministro per le Pari opportunità Andrea Ronchi, ministro per le Politiche Comunitarie Elio Vito, ministro per i Rapporti con il Parlamento Umberto Bossi, ministro per le Riforme per il Federalismo Giorgia Meloni, ministro per le Politiche per i Giovani Roberto Calderoli, ministro per la Semplificazione Normativa SOTTOSEGRETARI DI STATO Gianni Letta, sottosegretario di Stato alla Presidenza del Consiglio dei ministri, con le funzioni di segretario del Consiglio medesimo PRESIDENZA DEL CONSIGLIO DEI MINISTRI Maurizio Balocchi, Semplificazione normativa Paolo Bonaiuti, Editoria Michela Vittoria -

«Sì Al Centro Dell'ulivo» Dini Risponde Ai Popolari

05POL01A0507 05POL03A0507 FLOWPAGE ZALLCALL 13 14:43:22 07/07/96 K IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII Venerdì 5 luglio 1996 l’Unità pagina IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIPoliticaIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII 5 Marini apprezza. Il problema leadership: Prodi pensa al governo Bettino scomunica Amato «Sì al centro dell’Ulivo» e Martelli ROMA. E‘ dalle colonne del Dini risponde ai Popolari —quotidiano di An ‘Il Secolo d’Italia‘ che Bettino Craxi rinnova la sua ’scomunica‘ a Giuliano Amato ed Dini risponde ai Popolari: sono d’accordo, facciamo insie- esorta i socialisti italiani a riprende- re in proprio l’iniziativa politica. me il centro dell’Ulivo. E Marini: siamo aperti al dialogo. Craxi definisce l’adesione di Amato Ma nasce il problema della leadership. Chi deve essere il alla cosiddetta ‘Cosa 2‘ ’’una sem- capo: Prodi, come vorrebbero i Popolari o Dini, come au- plice operazione del tutto persona- spica Rinnovamento italiano? Masi: «Prodi è capo della le” e “tutt’altro che politica’’. E al 05POL01AF01 05POL01AF03 dottor Sottile manda un messaggio: coalizione e del governo, non può essere leader della fede- Not Found ’’la politica e‘ una cosa difficile e razione di centro». Silenzio del capo del governo. Per ora Not Found per fare politica bisogna rappre- non risponde alle proposte dei Popolari. 05POL01AF01 05POL01AF03 sentare qualcosa o qualcuno. Altri- GerardoBianco, menti ci si dedichi ad altro: per adestra,ilministro esempio, a scrivere libri...’’. degliEsteri L’appello ai socialisti da Ham- RITANNA ARMENI LambertoDini, mamet e‘ dunque a “rinascere da ROMA. Marini propone a Dini tuazione con grande attenzione. inbasso, soli’’. “Perche‘ se non stai da solo - —di costruire insieme un centro più Ma in questa fibrillazione della EnricoBoselli dice Craxi al suo intervistatore- sei forte dell’Ulivo.