Origins of Fascism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

Corrado GINI B. 23 May 1884 - D

Corrado GINI b. 23 May 1884 - d. 13 March 1965 Summary. From a strictly statistical point of view, Gini’s contributions per- tain mainly to mean values and variability and association between statistical variates, with original contributions also to economics, sociology, demogra- phy and biology. The historical context of his life and his personality helped make him the doyen of Italian statistics. Corrado Gini was born in Motta di Livenza (in the Province of Treviso in the North East of Italy. He was the son of rich landowners. He died in Rome in 1965. In 1905 he graduated in law from the University of Bologna. His degree thesis Il sesso dal punto di vista statistico (Gender from a Statistical Point of View), which was published in 1908, soon showed that his interests were not of a juridical nature even if “his study of the law, however, gave him a taste and a capacity for subtle arguments tending to submit the facts to logic and so to organise and dominate them” [3, p.3]. During university he attended additionally some mathematics and biology courses. His university career advanced rapidly. In fact in 1909 he was already temporary professor of Statistics at the University of Cagliari and in 1910, at only 26, he acceded to the Chair of Statistics at the same University. In 1913 he moved to the University of Padua and from 1927 he held the Chair of Statistics at the University of Rome. Between 1926 and 1932 he was President of the Central Institute of Statis- tics (ISTAT) and during this period he organised and co-ordinated the na- tional statistical services, bringing them to a good and efficient technical level despite various difficulties. -

Introduction Thinking Fascism and Populism in Terms of the Past

Introduction Thinking Fascism and Populism in Terms of the Past Representing a historian’s inquiry into how and why fascism morphed into populism in history, this book describes the dicta- torial genealogies of modern populism. It also stresses the sig- nifi cant diff erences between populism as a form of democracy and fascism as a form of dictatorship. It rethinks the conceptual and historical experiences of fascism and populism by assessing their elective ideological affi nities and substantial political dif- ferences in history and theory. A historical approach means not subordinating lived experiences to models or ideal types but rather stressing how the actors saw themselves in contexts that were both national and transnational. It means stressing varied contingencies and manifold sources. History combines evidence with interpretation. Ideal types ignore chronology and the cen- trality of historical processes. Historical knowledge requires accounting for how the past is experienced and explained through narratives of continuities and change over time. Against an idea of populism as an exclusively European or American phenomenon, I propose a global reading of its historical 1 2 / Introduction itineraries. Disputing generic theoretical defi nitions that reduce populism to a single sentence, I stress the need to return populism to history. Distinctive, and even opposed, forms of left- and right- wing populism crisscross the world, and I agree with historians like Eric Hobsbawm that left and right forms of populism cannot be confl ated simply because they are often antithetical.1 While populists on the left present those who are opposed to their politi- cal views as enemies of the people, populists on the right connect this populist intolerance of alternative political views with a con- ception of the people formed on the basis of ethnicity and country of origin. -

Italian Fascism Between Ideology and Spectacle

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 1 • Issue 2 • 2005 doi:10.32855/fcapital.200502.014 Italian Fascism between Ideology and Spectacle Federico Caprotti In April 1945, a disturbing scene was played out at a petrol station in Piazzale Loreto, in central Milan. Mussolini’s body was displayed for all to see, hanging upside down, together with those of other fascists and of Claretta Petacci, his mistress. Directly, the scene showed the triumph of the partisans, whose efforts against the Nazis had greatly accelerated the liberation of the North of Italy. The Piazzale Loreto scene was both a victory sign and a reprisal. Nazis and fascists had executed various partisans and displayed their bodies in the same place earlier in the war. Indirectly, the scene was a symbolic reversal of what had until then been branded as historical certainty. Piazzale Loreto was a public urban spectacle aimed at showing the Italian people that fascism had ended. The Duce was now displayed as a gruesome symbol of defeat in the city where fascism had first developed. More than two decades of fascism were symbolically overcome through a barbaric catharsis. The concept of spectacle has been applied to Italian fascism (Falasca-Zamponi 2000) in an attempt to conceptualize and understand the relationship between fascist ideology and its external manifestations in the public, symbolic, aesthetic, and urban spheres. This paper aims to further develop the concept of fascism as a society of spectacle by elaborating a geographical understanding of Italian fascism as a material phenomenon within modernity. Fascism is understood as an ideological construct (on which the political movement was based) which was expressed in the symbolic and aesthetic realm; its symbolism and art however are seen as having been rooted in material, historical specificity. -

QUALESTORIA. Rivista Di Storia Contemporanea. L'italia E La

«Qualestoria» n.1, giugno 2021, pp. 163-186 DOI: 10.13137/0393-6082/32191 https://www.openstarts.units.it/handle/10077/21200 163 Culture, arts, politics. Italy in Ivan Meštrović’s and Bogdan Radica’s discourses between the two World Wars di Maciej Czerwiński In this article the activity and discourses of two Dalmatian public figures are taken into consideration: the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and the journalist Bogdan Radica. They both had an enormous influence on how the image of Italy was created and disseminated in Yugoslavia, in particular in the 1920s and 1930s. The analysis of their discourses is interpreted in terms of the concept of Dalmatia within a wider Mediterranean basin which also refers to two diverse conceptualizations of Yugoslavism, cultural and politi- cal. Meštrović’s vision of Dalmatia/Croatia/Yugoslavia was based on his rural hinterland idiom enabling him to embrace racial and cultural Yugoslavism. In contrast, Radica, in spite of having a pro-Yugoslav orientation during the same period, did not believe in race, so for him the idea of Croat-Serb unity was more a political issue (to a lesser extent a cultural one). Keywords: Dalmatia, Yugoslav-Italian relationships, Croatianness, Yugoslavism, Bor- derlands Parole chiave: Dalmazia, Relazioni Jugoslavia-Italia, Croaticità, Jugoslavismo, Aree di confine Introduction This article takes into consideration the activity and discourses of the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and the journalist Bogdan Radica1. The choice of these two figures from Dalmatia, though very different in terms of their profession and political status in the interwar Yugoslav state (1918-41), has an important justification. Not only they both were influenced by Italian culture and heritage (displaying the typical Dalmatian ambivalence towards politics), but they also evaluated Italian heritage and politics in the Croatian/Yugoslav public sphere. -

Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights, II Author(S): Karl Loewenstein Source: the American Political Science Review, Vol

Militant Democracy and Fundamental Rights, II Author(s): Karl Loewenstein Source: The American Political Science Review, Vol. 31, No. 4 (Aug., 1937), pp. 638-658 Published by: American Political Science Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1948103 Accessed: 07-08-2018 08:47 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Political Science Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Political Science Review This content downloaded from 35.176.47.6 on Tue, 07 Aug 2018 08:47:36 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms MILITANT DEMOCRACY AND FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS, II* KARL LOEWENSTEIN Amherst College II Some Illustrations of Militant Democracy. Before a more system- atic -account of anti-fascist legislation in Europe is undertaken, recent developments in several countries may be reviewed as illus- trating what militant democracy can achieve against subversive extremism when the will to survive is coupled with appropriate measures for combatting fascist techniques. 1. Finland: From the start, the Finnish Republic was particu- larly exposed to radicalism both from left and right. The newly established state was wholly devoid of previous experience in self- government, shaken by violent nationalism, bordered by bolshevik Russia, yet within the orbit of German imperialism; no other country seemed more predestined to go fascist. -

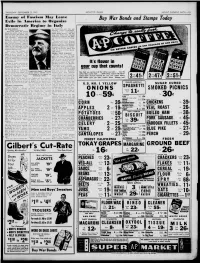

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

Corrado Gini: Professor of Statistics in Padua, 1913Ð19251

Statistica Applicata - Italian Journal of Applied Statistics Vol. 28 (2-3) 115 CORRADO GINI: PROFESSOR OF STATISTICS IN PADUA, 1913–19251 Silio Rigatti Luchini University of Padua, Italy2 Abstract This paper is concerned with the period 1913-1925 during which Corrado Gini was a professor of Statistics at the University of Padua. We describe the situation of statistics in the Italian academia before his enrolment at the Faculty of Law and then his activities in this faculty first as an adjunct professor and then of full professor of statistics. He founded a laboratory of statistics, similar to that he established at the University of Cagliari, and in 1924 the first Italian institute of statistics, in which students could gain a degree in statistics. He was very active in statistical research so that most of the innovation he introduced in statistics was already published before the Great War. During the war, he was first a soldier of the Italian army and then he collaborated with the national government in conducting many important surveys at national level. In 1920 he founded also the international journal Metron. In 1925 he moved from the University of Padua to that of Rome. Keywords: Corrado Gini; University of Padua, Institute of Statistics; Metron. 1. INTRODUCTION Corrado Gini was born on 23 May 1884 in Motta di Livenza, Treviso Province, to Lavinia Locatelli and Luciano Gini, a couple who belonged to the upper-middle agrarian class. He died in Rome on 13 March 1965. After graduating with a law degree from the University of Bologna in 1905, he advanced rapidly in his academic career. -

ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS in DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010

BEYOND THE DEMOCRATIC STATE: ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS IN DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science 2014 This thesis entitled: Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory written by Brian Carl Bernhardt has been approved for the Department of Political Science Steven Vanderheiden, Chair Michaele Ferguson David Mapel James Martel Alison Jaggar Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Bernhardt, Brian Carl (Ph.D., Political Science) Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory Thesis directed by Associate Professor Steven Vanderheiden Though democracy has achieved widespread global popularity, its meaning has become increasingly vacuous and citizen confidence in democratic governments continues to erode. I respond to this tension by articulating a vision of democracy inspired by anti-authoritarian theory and social movement practice. By anti-authoritarian, I mean a commitment to individual liberty, a skepticism toward centralized power, and a belief in the capacity of self-organization. This dissertation fosters a conversation between an anti-authoritarian perspective and democratic theory: What would an account of democracy that begins from these three commitments look like? In the first two chapters, I develop an anti-authoritarian account of freedom and power. -

Dissertation Full Draft 06 01 18

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO “Nothing is Going to be Named After You”: Ethical Citizenship Among Citizen Activists in Bosnia-Herzegovina A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Natasa Garic-Humphrey Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Postero, Chair Professor Joseph Hankins Professor Martha Lampland Professor Patrick Patterson Professor Saiba Varma 2018 Copyright Natasa Garic-Humphrey, 2018 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Natasa Garic-Humphrey is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2018 iii To: My mom and dad, who supported me unselfishly. My Clinton and Alina, who loved me unconditionally. My Bosnian family and friends, who shared with me their knowledge. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ...................................................................................................................... iii Dedication ............................................................................................................................. iv Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................v -

Fascist Italy's Illiberal Cultural Networks Culture, Corporatism And

Genealogie e geografie dell’anti-democrazia nella crisi europea degli anni Trenta Fascismi, corporativismi, laburismi a cura di Laura Cerasi Fascist Italy’s Illiberal Cultural Networks Culture, Corporatism and International Relations Benjamin G. Martin Uppsala University, Sweden Abstract Italian fascists presented corporatism, a system of sector-wide unions bring- ing together workers and employers under firm state control, as a new way to resolve tensions between labour and capital, and to reincorporate the working classes in na- tional life. ‘Cultural corporatism’ – the fascist labour model applied to the realm of the arts – was likewise presented as a historic resolution of the problem of the artist’s role in modern society. Focusing on two art conferences in Venice in 1932 and 1934, this article explores how Italian leaders promoted cultural corporatism internationally, creating illiberal international networks designed to help promote fascist ideology and Italian soft power. Keywords Fascism. Corporatism. State control. Labour. Capital. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 Broadcasting Cultural Corporatism. – 3 Venice 1932: Better Art Through Organisation. – 4 Italy’s International Cultural Outreach: Strategies and Themes. – 5 Venice 1934: Art and the State, Italy and the League. – 6 Conclusion. 1 Introduction The great ideological conflict of the interwar decades was a clash of world- views and visions of society, but it also had a quite practical component: which ideology could best respond to the concrete problems of the age? Problems like economic breakdown, mass unemployment, and labour unrest were not only practical, of course: they seemed linked to a broader breakdown of so- Studi di storia 8 e-ISSN 2610-9107 | ISSN 2610-9883 ISBN [ebook] 978-88-6969-317-5 | ISBN [print] 978-88-6969-318-2 Open access 137 Published 2019-05-31 © 2019 | cb Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License DOI 10.30687/978-88-6969-317-5/007 Martin Fascist Italy’s Illiberal Cultural Networks.