Troy and Homer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________May 22, 2008 I, _________________________________________________________,Kristin Marie Barry hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Architecture in: College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning It is entitled: The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Elizabeth Riorden _______________________________Rebecca Williamson _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact Kristin Barry Bachelor of Science in Architecture University of Cincinnati May 30, 2008 Submittal for Master of Architecture Degree College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning Prof. Elizabeth Riorden Abstract Although various resources have been provided at archaeological ruins for site interpretation, a recent change in education trends has led to a wider audience attending many international archaeological sites. An innovation in museum typology is needed to help tourists interpret the artifacts that been found at the site in a contextual manner. Through a study of literature by experts such as Victoria Newhouse, Stephen Wells, and other authors, and by analyzing successful interpretive center projects, I have developed a document outlining the reasons for on-site interpretive centers and their functions and used this material in a case study at the site of ancient Troy. My study produced a research document regarding museology and design strategy for the physical building, and will be applicable to any new construction on a sensitive site. I hope to establish a precedent that sites can use when adapting to this new type of visitors. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank a number of people for their support while I have been completing this program. -

Turkeyâ•Žs Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities

International Journal of Legal Information the Official Journal of the International Association of Law Libraries Volume 38 Article 12 Issue 2 Summer 2010 7-1-2010 Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities Kathleen Price Levin College of Law, University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli The International Journal of Legal Information is produced by The nI ternational Association of Law Libraries. Recommended Citation Price, Kathleen (2010) "Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities," International Journal of Legal Information: Vol. 38: Iss. 2, Article 12. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli/vol38/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Legal Information by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities KATHLEEN PRICE* “Every flower is beautiful in its own garden. Every antiquity is beautiful in its own country.” --Sign in Ephesus Museum lobby, quoted in Lonely Planet Turkey (11th ed.) at 60. “History is beautiful where it belongs.”—OzgenAcar[Acar Erghan] , imprinted on posters in Turkish libraries, classrooms, public buildings and shops and quoted in S. Waxman, Loot at 151; see also S. Waxman ,Chasing the Lydian Hoard, Smithsonian.com, November 14, 2008. The movement of cultural property1 from the vanquished to the victorious is as old as history. -

Seven Churches of Revelation Turkey

TRAVEL GUIDE SEVEN CHURCHES OF REVELATION TURKEY TURKEY Pergamum Lesbos Thyatira Sardis Izmir Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Samos Ephesus Laodicea Aegean Sea Patmos ASIA Kos 1 Rhodes ARCHEOLOGICAL MAP OF WESTERN TURKEY BULGARIA Sinanköy Manya Mt. NORTH EDİRNE KIRKLARELİ Selimiye Fatih Iron Foundry Mosque UNESCO B L A C K S E A MACEDONIA Yeni Saray Kırklareli Höyük İSTANBUL Herakleia Skotoussa (Byzantium) Krenides Linos (Constantinople) Sirra Philippi Beikos Palatianon Berge Karaevlialtı Menekşe Çatağı Prusias Tauriana Filippoi THRACE Bathonea Küçükyalı Ad hypium Morylos Dikaia Heraion teikhos Achaeology Edessa Neapolis park KOCAELİ Tragilos Antisara Abdera Perinthos Basilica UNESCO Maroneia TEKİRDAĞ (İZMİT) DÜZCE Europos Kavala Doriskos Nicomedia Pella Amphipolis Stryme Işıklar Mt. ALBANIA Allante Lete Bormiskos Thessalonica Argilos THE SEA OF MARMARA SAKARYA MACEDONIANaoussa Apollonia Thassos Ainos (ADAPAZARI) UNESCO Thermes Aegae YALOVA Ceramic Furnaces Selectum Chalastra Strepsa Berea Iznik Lake Nicea Methone Cyzicus Vergina Petralona Samothrace Parion Roman theater Acanthos Zeytinli Ada Apamela Aisa Ouranopolis Hisardere Dasaki Elimia Pydna Barçın Höyük BTHYNIA Galepsos Yenibademli Höyük BURSA UNESCO Antigonia Thyssus Apollonia (Prusa) ÇANAKKALE Manyas Zeytinlik Höyük Arisbe Lake Ulubat Phylace Dion Akrothooi Lake Sane Parthenopolis GÖKCEADA Aktopraklık O.Gazi Külliyesi BİLECİK Asprokampos Kremaste Daskyleion UNESCO Höyük Pythion Neopolis Astyra Sundiken Mts. Herakleum Paşalar Sarhöyük Mount Athos Achmilleion Troy Pessinus Potamia Mt.Olympos -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

1957'Den Bugüne Türkiye'deki İtalyan Arkeoloji Heyetleri

Missioni Archeologiche Italiane in Turchia dal 1957 ad Oggi 1957’den Bugüne .. Türkiye’deki İtalyan Arkeoloji Heyetleri Il 1957 ha segnato l'avvio delle attività di ricerca archeologica italiana in Turchia. Questa pubblicazione è dedicata alle numerose missioni archeologiche italiane che da allora continuano l'opera di ricostruzione della millenaria storia di questo Paese e costituiscono un eccezionale ponte culturale tra Italia e Turchia. Türkiye’deki İtalyan arkeolojik araştırmaları 1957 yılında başlamıştır. Bu yayın, o zamandan beri bu topraklardaki binlerce yıllık tarihin yeniden yazılmasını sağlayan ve iki ülke arasında mükemmel bir kültürel köprü oluşturan çok sayıdaki İtalyan arkeoloji heyetine adanmıştır. 1 Saluto dell’Ambasciatore d’Italia in Turchia Luigi Mattiolo uesta pubblicazione intende rendere omaggio alla nostro Paese di proporsi come uno straordinario punto di Qprofessionalità, all’entusiasmo ed alla dedizione che gli riferimento in materia di ricerca, tutela e valorizzazione dei archeologi ed i ricercatori italiani quotidianamente beni culturali a livello globale. Si tratta infatti di un settore in profondono nella complessa attività di studio, tutela e cui l’Italia è in grado di esprimere professionalità di spicco a valorizzazione del patrimonio storico-architettonico di cui le livello scientifico-accademico e - in un ponte ideale di numerose civiltà che nel corso dei secoli si sono succedute collegamento fra passato e futuro - tecnologie, design, sistemi hanno lasciato traccia nel territorio dell’odierna Turchia. e materiali all’avanguardia. Non è un caso che siano sempre L’indagine archeologica, attraverso l’analisi di reperti e più numerose le aziende italiane specializzate che offrono testimonianze, risulta infatti un passaggio fondamentale per sistemi e servizi avanzati per il restauro, la tutela e la ricostruire l’eredità storica ed - in un’ultima analisi - l’identità valorizzazione del patrimonio archeologico ed architettonico. -

Stable Lead Isotope Studies of Black Sea Anatolian Ore Sources and Related Bronze Age and Phrygian Artefacts from Nearby Archaeological Sites

Archaeometry 43, 1 (2001) 77±115. Printed in Great Britain STABLE LEAD ISOTOPE STUDIES OF BLACK SEA ANATOLIAN ORE SOURCES AND RELATED BRONZE AGE AND PHRYGIAN ARTEFACTS FROM NEARBY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES. APPENDIX: NEW CENTRAL TAURUS ORE DATA E. V. SAYRE, E. C. JOEL, M. J. BLACKMAN, Smithsonian Center for Materials Research and Education, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560, USA K. A. YENER Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, 1155 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA and H. OÈ ZBAL Faculty of Arts and Sciences, BogÆazicËi University, Istanbul, Turkey The accumulated published database of stable lead isotope analyses of ore and slag specimens taken from Anatolian mining sites that parallel the Black Sea coast has been augmented with 22 additional analyses of such specimens carried out at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Multivariate statistical analysis has been used to divide this composite database into ®ve separate ore source groups. Evidence that most of these ore sources were exploited for the production of metal artefacts during the Bronze Age and Phrygian Period has been obtained by statistically comparing to them the isotope ratios of 184 analysed artefacts from nine archaeological sites situated within a few hundred kilometres of these mining sites. Also, Appendix B contains 36 new isotope analyses of ore specimens from Central Taurus mining sites that are compatible with and augment the four Central Taurus Ore Source Groups de®ned in Yener et al. (1991). KEYWORDS: BLACK SEA, CENTRAL TAURUS, ANATOLIA, METAL, ORES, ARTEFACTS, BRONZE AGE, MULTIVARIATE, STATISTICS, PROBABILITIES INTRODUCTION This is the third in a series of papers in which we have endeavoured to evaluate the present state of the application of stable lead isotope analyses of specimens from metallic ore sources and of ancient artefacts from Near Eastern sites to the inference of the probable origins of such artefacts. -

How to Restart an Oracle: Politics, Propaganda, and the Oracle of Apollo

How to Restart an Oracle: Politics, Propaganda, and the Oracle of Apollo at Didyma c.305-300 BCE The Sacred Spring at Didyma dried up when the Persians deported the Branchidae to central Asia at the conclusion of the Ionian revolt c.494. It remained barren throughout the fifth and most of the fourth centuries and thus prophecy did not flow. However, when Alexander the Great liberated Miletus in 334, the spring was reborn and with it returned the gift of prophecy. After nearly two centuries, the new oracle at Didyma was not the same as the old one. This begs the question, how does one restart an oracle? The usual account is that Alexander appointed a new priestess, who immediately predicted his victory over Persia and referred to him as a god. In the historical tradition, largely stemming from Callisthenes, the renewed oracle is thus linked to Alexander, but words are wind and tradition can be manipulated. There are issues with the canonical chronology: Miletus reverted briefly to Persian control in Alexander’s wake; the Branchidae, the hereditary priests, still lived in central Asia (Hammond 1998; Parke 1985); and, most tellingly, construction on a new temple did not start for another thirty years. In fact, the renewal of the oracle only appears after Seleucus, who supposedly received three favorable oracles in 334, found the original cult statue and returned it to Miletus (Paus. 1.16.3). In the satiric account of the prophet Alexander, Lucian of Samosata declares the oracles of old, including Delphi, Delos, Claros, and Branchidae (Didyma), became wealthy by exploiting the credulity and fears of wealthy tyrants (8). -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

An Ancient Cave Sanctuary Underneath the Theatre of Miletus

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Philipp Niewöhner An Ancient Cave Sanctuary underneath the Theatre of Miletus, Beauty, Mutilation, and Burial of Ancient Sculpture in Late Antiquity, and the History of the Seaward Defences aus / from Archäologischer Anzeiger Ausgabe / Issue 1 • 2016 Seite / Page 67–156 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa/1931/5962 • urn:nbn:de:0048-journals.aa-2016-1-p67-156-v5962.3 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion der Zentrale | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/aa ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition 2510-4713 Verlag / Publisher Ernst Wasmuth Verlag GmbH & Co. Tübingen ©2017 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Mit dem Herunterladen erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen (https://publications.dainst.org/terms-of-use) von iDAI.publications an. Die Nutzung der Inhalte ist ausschließlich privaten Nutzerinnen / Nutzern für den eigenen wissenschaftlichen und sonstigen privaten Gebrauch gestattet. Sämtliche Texte, Bilder und sonstige Inhalte in diesem Dokument unterliegen dem Schutz des Urheberrechts gemäß dem Urheberrechtsgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Die Inhalte können von Ihnen nur dann genutzt und vervielfältigt werden, wenn Ihnen dies im Einzelfall durch den Rechteinhaber oder die Schrankenregelungen des Urheberrechts gestattet ist. Jede Art der Nutzung zu gewerblichen Zwecken ist untersagt. Zu den Möglichkeiten einer Lizensierung von Nutzungsrechten wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an die verantwortlichen Herausgeberinnen/Herausgeber der entsprechenden Publikationsorgane oder an die Online-Redaktion des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts ([email protected]). -

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

ROUTES and COMMUNICATIONS in LATE ROMAN and BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (Ca

ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY TÜLİN KAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. D. Burcu ERCİYAS Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna GÜVEN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale ÖZGENEL (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ufuk SERİN (METU, ARCH) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe F. EROL (Hacı Bayram Veli Uni., Arkeoloji) Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine SÖKMEN (Hitit Uni., Arkeoloji) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Tülin Kaya Signature : iii ABSTRACT ROUTES AND COMMUNICATIONS IN LATE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE ANATOLIA (ca. 4TH-9TH CENTURIES A.D.) Kaya, Tülin Ph.D., Department of Settlement Archaeology Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. -

Guidelines for Handouts JM

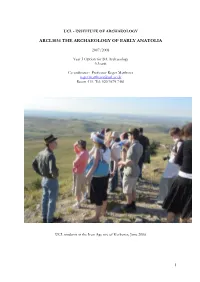

UCL - INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY ARCL3034 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF EARLY ANATOLIA 2007/2008 Year 3 Option for BA Archaeology 0.5 unit Co-ordinator: Professor Roger Matthews [email protected] Room 411. Tel: 020 7679 7481 UCL students at the Iron Age site of Kerkenes, June 2006 1 AIMS To provide an introduction to the archaeology of early Anatolia, from the Palaeolithic to the Iron Age. To consider major issues in the development of human society in Anatolia, including the origins and evolution of sedentism, agriculture, early complex societies, empires and states. To consider the nature and interpretation of archaeological sources in approaching the past of Anatolia. To familiarize students with the conduct and excitement of the practice of archaeology in Anatolia, through an intensive 2-week period of organized site and museum visits in Turkey. OBJECTIVES On successful completion of this course a student should: Have a broad overview of the archaeology of early Anatolia. Appreciate the significance of the archaeology of early Anatolia within the broad context of the development of human society. Appreciate the importance of critical approaches to archaeological sources within the context of Anatolia and Western Asia. Understand first-hand the thrill and challenge of practicing archaeology in the context of Turkey. COURSE INFORMATION This handbook contains the basic information about the content and administration of the course. Additional subject-specific reading lists and individual session handouts will be given out at appropriate points in the course. If students have queries about the objectives, structure, content, assessment or organisation of the course, they should consult the Course Co-ordinator.