The Other Islands of Aloha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APRIL 1995 R!' a ! DY April 1995 Number 936

APRIL 1995 R!' A ! DY April 1995 Number 936 I Earthquake epicen.,.s -IN THE SEA ?ABOVE THE SEA 4 The wave 22Weather prediction 6 What's going on? 24What is El Nino? 8 Knowledge is power 26Clouds, typhoons and hurricanes 10 Bioluminescence 28Highs, lows and fronts 11 Sounds in the sea 29Acid rain 12 Why is the ocean blue? 30 Waves 14 The sea floor 31The Gulf Stream 16 Going with the floe 32 The big picture: blue and littoral waters 18 Tides *THE ENVIRONMENT 34 TheKey West Campaign 19 Navyoceanographers 36 What's cookin' on USS Theodore Roosevek c 20Sea lanes of communication 38 GW Sailors put the squeeze on trash 40 Cleaning up on the West Coast 42Whale flies south after rescue 2 CHARTHOUSE M BEARINGS 48 SHIPMATES On the Covers Front cover: View of the Western Pacific takenfrom Apollo 13, in 1970. Photo courtesy of NASA. Opposite page: "Destroyer Man,"oil painting by Walter Brightwell. Back cover: EM3 Jose L. Tapia aboard USS Gary (FFG 51). Photo by JO1 Ron Schafer. so ” “I Charthouse Drug Education For Youth program seeks sponsors The Navy is looking for interested active and reserve commandsto sponsor the Drug Education For Youth (DEFY) program this summer. In 1994, 28 military sites across the nation helped more than 1,500 youths using the prepackaged innovative drug demand reduction program. DEFY reinforces self-esteem, goal- setting, decision-making and sub- stance abuse resistance skills of nine to 12-year-old children. This is a fully- funded pilot program of theNavy and DOD. DEFY combines a five to eight- day, skill-building summer camp aboard a military base with a year-long mentor program. -

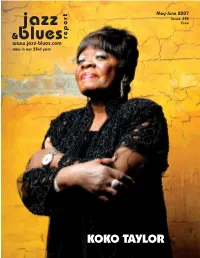

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Did You Receive This Copy of Jazzweek As a Pass Along?

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • Feb. 6, 2006 Volume 2, Number 11 • $7.95 In This Issue: Surprises at Berklee 60th Anniversary Concert . 4 Classical Meets Jazz in JALC ‘Jazz Suite’ Debut . 5 ALJO Embarks On Tour . 8 News In Brief . 6 Reviews and Picks . 15 Jazz Radio . 18 Smooth Jazz Radio. 25 Industry Legend Radio Panels. 24, 29 BRUCE LUNDVALL News. 4 Part One of our Two-part Q&A: page 11 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Jae Sinnett #1 Smooth Album – Richard Elliot #1 Smooth Single – Brian Simpson JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger n part one of our two part interview with Bruce Lundvall, the MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson Blue Note president tells music editor Tad Hendrickson that Iin his opinion radio indeed does sell records. That’s the good CONTRIBUTING EDITORS news. Keith Zimmerman Kent Zimmerman But Lundvall points out something that many others have CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ pointed out in recent years: radio doesn’t make hits. As he tells Tad, PHOTOGRAPHER “When I was a kid I would hear a new release and they would play Tom Mallison it over and over again. Not like Top 40, but over a period of weeks PHOTOGRAPHY you’d hear a tune from the new Hank Mobley record. That’s not Barry Solof really happening much any more.” Lundvall understands the state Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre of programming on mostly non-commercial jazz stations, and ac- ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy knowledges that kind of focused airplay doesn’t happen. Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or This ties into my question of last week – does mainstream jazz email: [email protected] radio play too much music that’s only good, but not great? I’ve SUBSCRIPTIONS: received a few comments; please email me with your thoughts on Free to qualified applicants this at [email protected]. -

Discografía De BLUE NOTE Records Colección Particular De Juan Claudio Cifuentes

CifuJazz Discografía de BLUE NOTE Records Colección particular de Juan Claudio Cifuentes Introducción Sin duda uno de los sellos verdaderamente históricos del jazz, Blue Note nació en 1939 de la mano de Alfred Lion y Max Margulis. El primero era un alemán que se había aficionado al jazz en su país y que, una vez establecido en Nueva York en el 37, no tardaría mucho en empezar a grabar a músicos de boogie woogie como Meade Lux Lewis y Albert Ammons. Su socio, Margulis, era un escritor de ideología comunista. Los primeros testimonios del sello van en la dirección del jazz tradicional, por entonces a las puertas de un inesperado revival en plena era del swing. Una sentida versión de Sidney Bechet del clásico Summertime fue el primer gran éxito de la nueva compañía. Blue Note solía organizar sus sesiones de grabación de madrugada, una vez terminados los bolos nocturnos de los músicos, y pronto se hizo popular por su respeto y buen trato a los artistas, que a menudo podían involucrarse en tareas de producción. Otro emigrante aleman, el fotógrafo Francis Wolff, llegaría para unirse al proyecto de su amigo Lion, creando un tandem particulamente memorable. Sus imágenes, unidas al personal diseño del artista gráfico Reid Miles, constituyeron la base de las extraordinarias portadas de Blue Note, verdadera seña de identidad estética de la compañía en las décadas siguientes mil veces imitada. Después de la Guerra, Blue Note iniciaría un giro en su producción musical hacia los nuevos sonidos del bebop. En el 47 uno de los jóvenes representantes del nuevo estilo, el pianista Thelonious Monk, grabó sus primeras sesiones Blue Note, que fue también la primera compañía del batería Art Blakey. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Rhodesian Conference Stalemate Is Broken

The weather Inside today Mostly cloudy, warm, today. A few Area news — 1-B Editorial ........4-A showers expected. High 60. Goudy and Classified . 5-B-7-B Obituaries ... 12-A continued mild tonight and Sunday. Comics........ 11-A Week-Review . 2-A Showers likely. Low toniqht near SO, PA <a»^ “ Tfce BHght One** Churches ....... 8-A Wings............7-A high Sunday 55-60. National weather SECTIONS Dear Abby ... U-A Sports__ 2-B-3-B forecast map on Page 5-B. lINSifiE MANOBQESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 27.1«8 - VOL. XCVI, No .« jpRiCEi EfFTEEN CENTS fV Rhodesian conference m &-V4C stalemate is broken / GENEVA, Switzerland (UPI) - independence by March 1, 1978. terim government to create even dependence to Zimbabwe (Rhodesia) The monthlong stalemate has ended The two men again rejected the wider disagreement among has been delayed by one month while in the Rhodesia peace talks and the British compromise formula Friday, delegations. some people are wining, dining, ml conference now can move on to con demanding two amendments to the A particularly critical subject is bickering and dithering in expensive, 6t sider the makeup of the interim proposal. They met with Richard and whether blacks or whites will luxurious and posh hotels,” government that wiil rule until power came away saying "Britain has dominate the transitional Muzorewa said. is turned over to the country’s black accepted our amendments.” government's Department of He told Richard he may have to majority. British conference CHiair- Mugabe and Nkomo said they will Defense and Security. consider leaving Geneva unless there man Ivor Richard said Friday he will issue a joint'statement this weekend The break in the Stalemate is genuine movement next week. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title To rise by Enterprize : : Opportunism and Self-Interest in British Atlantic Literature, 1700- 1854 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0253c3bv Author Filkow, Amie Bess Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “To rise by Enterprize”: Opportunism and Self-Interest in British Atlantic Literature, 1700-1854 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Amie Bess Filkow Committee in charge: Professor Sara Johnson, Chair Professor Lisa Lampert-Weissig Professor Kathryn Shevelow Professor Cynthia Truant Professor Daniel Vitkus 2014 Copyright Amie Bess Filkow, 2014 All rights reserved. SIGNATURE PAGE The Dissertation of Amie Bess Filkow is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION DEDICATION For my mother, the reader and my father, the entrepreneur. And for Paul, for everything. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

Bunkering of Liquefied Natural Gas-Fueled Marine Vessels in North America 2 ND EDITION

Bunkering of Liquefied Natural Gas-fueled Marine Vessels in North America 2 ND EDITION © TOTE Our Mission The mission of ABS is to serve the public interest as well as the needs of our members and clients by promoting the security of life and property and preserving the natural environment. Health, Safety, Quality & Environmental Policy We will respond to the needs of our members, clients and the public by delivering quality service in support of our mission that provides for the safety of life and property and the preservation of the marine environment. We are committed to continually improving the effectiveness of our health, safety, quality and environmental (HSQE) performance and management system with the goal of preventing injury, ill health and pollution. We will comply with all applicable legal requirements as well as any additional requirements ABS subscribes to which relate to HSQE aspects, objectives and targets. Table of Contents Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................................................................iv Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................................................x 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. What’s New .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Edo Japan: 14 a Closed Society

ABSS8_ch14.qxd 2/8/07 3:54 PM Page 304 Edo Japan: 14 A Closed Society FIGURE 14-1 This is a monument to Ranald MacDonald in Nagasaki, Japan. What does this monument indicate about Japanese attitudes toward him? 304 Unit 3 From Isolation to Adaptation ABSS8_ch14.qxd 2/8/07 3:54 PM Page 305 WORLDVIEW INQUIRY Geography In what ways might a country’s choice to remain isolated both reflect its worldview Knowledge Time and result from its worldview? Worldview Economy Beliefs 1848. Ranald MacDonald, a twenty-four-year-old Métis, Values Society insisted that he be set adrift in a small boat off the coast of Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan. he captain and crew of the Plymouth, the In This Chapter American whaling ship that Ranald T In the last chapter, your read MacDonald was leaving, tried to persuade the about the high value put on hon- young man to stay with them. Why did he want to our, duty, and harmony in Edo enter a country that was known to execute Japan. Japanese society differed strangers? When the rudder from his boat was later from the others you have studied found floating in the sea, word was sent to North in its desire and ability to cut America that the young Métis was dead. itself off from the rest of the Ranald MacDonald was the son of Princess world. In Europe from 1600 to Raven, a Chinook, and Archibald MacDonald, a the 1850s, the exchange of Scottish official of the Hudson’s Bay Company. -

“World Without End”: the Straits of Magellan Around 1600

chapter ten Apocalyptic Times in a “World without End”: The Straits of Magellan around 1600 SUSANNA BURGHARTZ From the beginning, intensive production in a plethora of media accom- panied the opening of new worlds and the exploration of new spaces and routes by Europeans – the Portuguese, Spaniards, Germans, French, and Dutch. Relaciones, travel accounts, pamphlets, (world) maps, and pictures processed the experiences of new places while creating new pictorial and literary worlds for an increasingly numerous European public. Thanks to printers, publishers, engravers, and cartographers, this process intensi- fied greatly in the second half of the sixteenth century in various Euro- pean centres. Antwerp in particular, and increasingly Amsterdam after its conquest by the Spanish in 1585, became print and representation markets of European significance, whose enormous multimedia produc- tivity in the form of pictures and maps would help to decisively shape Eu- rope’s world view, especially in the visual realm.1 Around the same time (c. 1580) the process of European expansion reached the next phase. With the appearance of England, and soon thereafter the Netherlands,2 as Spain’s and Portugal’s new rivals on the high seas, interest in the dis- covery of new routes and the control of known passages intensified. Thus in South America, the Straits of Magellan, already discovered in 1520, became the focus of national as well as confessional rivalries. The new political topicality was reflected in a corresponding presence of the Straits of Magellan across a range of media. The Straits, however, were not represented as simply a point of passage for travellers but rather as a powerful site of confrontation with human desires and their limits. -

The Other Islands of Aloha Scott Kramer and Hanae Kurihara Kramer

The Other Islands of Aloha scott kramer and hanae kurihara kramer A storm-beaten vessel arrived at the bustling seaport town of 81840, almost four months after having disappeared off the Japanese coast. The crew claimed that winter winds carried them to a lush island named Aina (Hawaiian D": land). Located somewhere to the south of Japan, this place was said to be inhabited by strange but amicable foreigners who wore grass hats and greeted one another by raising an arm into the air and saying (H. aloha: hello).1 The castaways’ colorful tale naturally attracted interest. As was dictated by Japanese law, a series of interviews had to be conducted before the merchant sailors were allowed to return to their villages.2 Government interviewers encouraged all six crewmen to recount their adventure, which they did with impressive detail. These inter- views reveal that these Japanese castaways had drifted to the remote Bonin Archipelago, where a group of Hawaiians and a few Caucasians had established a colony ten years earlier. Back in 1829, Richard Charlton, the first British consul to the Sandwich Islands (Hawai‘i), organized people to colonize an unin- habited archipelago recently “discovered” in the northwestern Pacific by the Englishman Frederick William Beechey. News of the archi- Scott Kramer received his master’s degree in history from the University of Hawai‘i. He is currently in Japan writing a book on the Bonin Archipelago. Hanae Kurihara Kramer is an " intercultural and global communication. vol. 47 (2013) 1 2 the hawaiian journal of history pelago untouched by civilization and free of native princes inspired Charlton to do his part to further British interests.3 He never received official permission or support from his government for the venture, but he hoped that someday his fellow countrymen would come to rec- ognize the strategic importance of the Bonin Archipelago and prop- erly incorporate them into the empire.