UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APRIL 1995 R!' a ! DY April 1995 Number 936

APRIL 1995 R!' A ! DY April 1995 Number 936 I Earthquake epicen.,.s -IN THE SEA ?ABOVE THE SEA 4 The wave 22Weather prediction 6 What's going on? 24What is El Nino? 8 Knowledge is power 26Clouds, typhoons and hurricanes 10 Bioluminescence 28Highs, lows and fronts 11 Sounds in the sea 29Acid rain 12 Why is the ocean blue? 30 Waves 14 The sea floor 31The Gulf Stream 16 Going with the floe 32 The big picture: blue and littoral waters 18 Tides *THE ENVIRONMENT 34 TheKey West Campaign 19 Navyoceanographers 36 What's cookin' on USS Theodore Roosevek c 20Sea lanes of communication 38 GW Sailors put the squeeze on trash 40 Cleaning up on the West Coast 42Whale flies south after rescue 2 CHARTHOUSE M BEARINGS 48 SHIPMATES On the Covers Front cover: View of the Western Pacific takenfrom Apollo 13, in 1970. Photo courtesy of NASA. Opposite page: "Destroyer Man,"oil painting by Walter Brightwell. Back cover: EM3 Jose L. Tapia aboard USS Gary (FFG 51). Photo by JO1 Ron Schafer. so ” “I Charthouse Drug Education For Youth program seeks sponsors The Navy is looking for interested active and reserve commandsto sponsor the Drug Education For Youth (DEFY) program this summer. In 1994, 28 military sites across the nation helped more than 1,500 youths using the prepackaged innovative drug demand reduction program. DEFY reinforces self-esteem, goal- setting, decision-making and sub- stance abuse resistance skills of nine to 12-year-old children. This is a fully- funded pilot program of theNavy and DOD. DEFY combines a five to eight- day, skill-building summer camp aboard a military base with a year-long mentor program. -

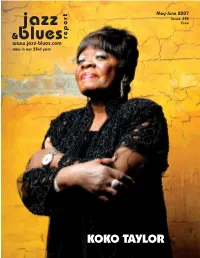

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Did You Receive This Copy of Jazzweek As a Pass Along?

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • Feb. 6, 2006 Volume 2, Number 11 • $7.95 In This Issue: Surprises at Berklee 60th Anniversary Concert . 4 Classical Meets Jazz in JALC ‘Jazz Suite’ Debut . 5 ALJO Embarks On Tour . 8 News In Brief . 6 Reviews and Picks . 15 Jazz Radio . 18 Smooth Jazz Radio. 25 Industry Legend Radio Panels. 24, 29 BRUCE LUNDVALL News. 4 Part One of our Two-part Q&A: page 11 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Jae Sinnett #1 Smooth Album – Richard Elliot #1 Smooth Single – Brian Simpson JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger n part one of our two part interview with Bruce Lundvall, the MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson Blue Note president tells music editor Tad Hendrickson that Iin his opinion radio indeed does sell records. That’s the good CONTRIBUTING EDITORS news. Keith Zimmerman Kent Zimmerman But Lundvall points out something that many others have CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ pointed out in recent years: radio doesn’t make hits. As he tells Tad, PHOTOGRAPHER “When I was a kid I would hear a new release and they would play Tom Mallison it over and over again. Not like Top 40, but over a period of weeks PHOTOGRAPHY you’d hear a tune from the new Hank Mobley record. That’s not Barry Solof really happening much any more.” Lundvall understands the state Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre of programming on mostly non-commercial jazz stations, and ac- ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy knowledges that kind of focused airplay doesn’t happen. Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or This ties into my question of last week – does mainstream jazz email: [email protected] radio play too much music that’s only good, but not great? I’ve SUBSCRIPTIONS: received a few comments; please email me with your thoughts on Free to qualified applicants this at [email protected]. -

The Discipline of Theseas

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR LITTERATUR, IDÉHISTORIA OCH RELIGION The Discipline of the Seas Piracy and polity in England: 1688–1698 Johan Berglund Björk Term: Spring 2020 Course ID: LIR207, 30 HEC Level: Master Supervisor: Johan Kärnfelt 1 Abstract Master’s thesis in history of ideas Title: The Discipline of the Seas: Piracy and Polity, 1688. Author: Johan Berglund Björk Year: Spring 2020 Department: The Faculty of Arts at the University of Gothenburg Supervisor: Johan Kärnfelt Examiner: Henrik Björk Keywords: Piracy; Henry Every; Matthew Tindall; Philip Meadows; subjecthood; sovereignty; jurisdiction. This thesis is a study of the changing legal and political climate surrounding piracy in England in the years 1688-1698, between the Glorious Revolution and the passing in parliament of the Piracy Act 1698. During this time views of piracy changed in London where pirates were no longer seen as beneficial, but instead as obstacles to orderly trade. The aim of this thesis is to investigate English legal and political-theoretical writing on piracy and sovereignty of the seas to further understanding of what kinds of legal spaces oceans were in early modern English political thought, and the role of pirates as actors in those spaces. This is achieved by a study of legal and theoretical texts, which focuses on the concepts subjecthood, jurisdiction and sovereignty in relation to piracy. I show that piracy became a blanket-term of delegitimization applied to former kings as well as poor sailors and that the English struggle for the suppression of piracy was ideological as well as practical. By contrasting legal and political theory with its realpolitikal context I show that diplomatic and economic concerns often eclipsed theory when judging pirates in legal praxis. -

Annales Historiques De La Révolution Française, 344 | Avril-Juin 2006 Cercles Politiques Et « Salons » Du Début De La Révolution (1789-1793) 2

Annales historiques de la Révolution française 344 | avril-juin 2006 La prise de parole publique des femmes Cercles politiques et « salons » du début de la Révolution (1789-1793) Olivier Blanc Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/5983 DOI : 10.4000/ahrf.5983 ISSN : 1952-403X Éditeur : Armand Colin, Société des études robespierristes Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 juin 2006 Pagination : 63-92 ISSN : 0003-4436 Référence électronique Olivier Blanc, « Cercles politiques et « salons » du début de la Révolution (1789-1793) », Annales historiques de la Révolution française [En ligne], 344 | avril-juin 2006, mis en ligne le 01 juin 2009, consulté le 01 mai 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/5983 ; DOI : 10.4000/ahrf.5983 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 1 mai 2019. Tous droits réservés Cercles politiques et « salons » du début de la Révolution (1789-1793) 1 Cercles politiques et « salons » du début de la Révolution (1789-1793) Olivier Blanc 1 L’influence, le crédit et le début de reconnaissance sociale1 dont les femmes des classes nobles et bourgeoises de la société française bénéficièrent à la toute fin du XVIIIe siècle, devaient subitement décliner avec la guerre totale et la politique de salut public qui en fut la conséquence. Durant cette longue période – de Valmy à Waterloo –, le pouvoir politique relégua aux oubliettes les beaux projets d’émancipation agités par Condorcet et Marie- Olympe de Gouges entre autres, et les nouvelles classes bourgeoises ne s’y intéressèrent pas comme en ont témoigné George Sand et d’autres femmes de la nouvelle génération. Si l’histoire a retenu que, pour les femmes, cette évolution fut une défaite en termes d’émancipation et de consécration légale de leur influence réelle, les documents issus des archives révèlent pourtant leur intérêt constant et leur participation active sous des formes inattendues et variées aux événements politiques de leur temps. -

Discografía De BLUE NOTE Records Colección Particular De Juan Claudio Cifuentes

CifuJazz Discografía de BLUE NOTE Records Colección particular de Juan Claudio Cifuentes Introducción Sin duda uno de los sellos verdaderamente históricos del jazz, Blue Note nació en 1939 de la mano de Alfred Lion y Max Margulis. El primero era un alemán que se había aficionado al jazz en su país y que, una vez establecido en Nueva York en el 37, no tardaría mucho en empezar a grabar a músicos de boogie woogie como Meade Lux Lewis y Albert Ammons. Su socio, Margulis, era un escritor de ideología comunista. Los primeros testimonios del sello van en la dirección del jazz tradicional, por entonces a las puertas de un inesperado revival en plena era del swing. Una sentida versión de Sidney Bechet del clásico Summertime fue el primer gran éxito de la nueva compañía. Blue Note solía organizar sus sesiones de grabación de madrugada, una vez terminados los bolos nocturnos de los músicos, y pronto se hizo popular por su respeto y buen trato a los artistas, que a menudo podían involucrarse en tareas de producción. Otro emigrante aleman, el fotógrafo Francis Wolff, llegaría para unirse al proyecto de su amigo Lion, creando un tandem particulamente memorable. Sus imágenes, unidas al personal diseño del artista gráfico Reid Miles, constituyeron la base de las extraordinarias portadas de Blue Note, verdadera seña de identidad estética de la compañía en las décadas siguientes mil veces imitada. Después de la Guerra, Blue Note iniciaría un giro en su producción musical hacia los nuevos sonidos del bebop. En el 47 uno de los jóvenes representantes del nuevo estilo, el pianista Thelonious Monk, grabó sus primeras sesiones Blue Note, que fue también la primera compañía del batería Art Blakey. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

Recherches Sur Diderot Et Sur L'encyclopédie, 39 | 2005 Quatorze Lettres Inédites De Sophie De Grouchy Et Des Éditeurs Des Œuvres Dit

Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie 39 | 2005 Varia Quatorze lettres inédites de Sophie de Grouchy et des éditeurs des Œuvres dites Complètes de Condorcet Jean-Nicolas Rieucau Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/rde/322 DOI : 10.4000/rde.322 ISSN : 1955-2416 Éditeur Société Diderot Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 décembre 2005 Pagination : 125-155Nous remercions A. Chassagne, P. Crépel et D. Varry pour leurs remarques sur une première version de cette présentation. Nous demeurons cependant seul responsable des imperfections qui y subsistent. ISSN : 0769-0886 Référence électronique Jean-Nicolas Rieucau, « Quatorze lettres inédites de Sophie de Grouchy et des éditeurs des Œuvres dites Complètes de Condorcet », Recherches sur Diderot et sur l'Encyclopédie [En ligne], 39 | 2005, mis en ligne le 08 décembre 2008, consulté le 30 juillet 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rde/ 322 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/rde.322 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 30 juillet 2021. Propriété intellectuelle Quatorze lettres inédites de Sophie de Grouchy et des éditeurs des Œuvres dit... 1 Quatorze lettres inédites de Sophie de Grouchy et des éditeurs des Œuvres dites Complètes de Condorcet Jean-Nicolas Rieucau 1 Traductrice de Smith, artiste peintre, épistolière, Sophie de Grouchy fut aussi, au lendemain de la mort de Condorcet (mars 1794), la principale éditrice de ses écrits. Elle fut en particulier responsable de la publication posthume de deux ouvrages, l’Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain [an III] et les Moyens d’apprendre à compter sûrement et avec facilité [an VII]. -

Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy

Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy EILEEN O’NEILL It has now been more than a dozen years since the Eastern Division of the APA invited me to give an address on what was then a rather innovative topic: the published contributions of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century women to philosophy.1 In that address, I highlighted the work of some sixty early modern women. I then said to the audience, “Why have I presented this somewhat interesting, but nonetheless exhausting . overview of seventeenth- and eigh- teenth-century women philosophers? Quite simply, to overwhelm you with the presence of women in early modern philosophy. It is only in this way that the problem of women’s virtually complete absence in contemporary histories of philosophy becomes pressing, mind-boggling, possibly scandalous.” My presen- tation had attempted to indicate the quantity and scope of women’s published philosophical writing. It had also suggested that an acknowledgment of their contributions was evidenced by the representation of their work in the scholarly journals of the period and by the numerous editions and translations of their texts that continued to appear into the nineteenth century. But what about the status of these women in the histories of philosophy? Had they ever been well represented within the histories written before the twentieth century? In the second part of my address, I noted that in the seventeenth century Gilles Menages, Jean de La Forge, and Marguerite Buffet produced doxogra- phies of women philosophers, and that one of the most widely read histories of philosophy, that by Thomas Stanley, contained a discussion of twenty-four women philosophers of the ancient world. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Research Programs in Preference and Belief Aggregation

1. Introduction: Research Programs in Preference and Belief Aggregation Norman Schofield 1 1.1 Preferences and Beliefs Political economy and social choice both have their origins in the Eighteenth Century, in the work of Adam Smith (1759, 1776) during the Scottish En lightenment and in the work of the Marquis de Condorcet (1785) just before the French Revolution.2 Since then, of course, political economy or economic theory has developed apace. However, it was only in the late 1940's that social choice was rediscovered (Arrow 1951; Black 1948, 1958), and only relatively recently has there been work connecting these two fields. The connection be tween political economy and social choice theory is the subject matter of this volume. Adam Smith's work leads, of course, to modern economic theory-the anal ysis of human incentives in the particular context of fixed resources, private goods, and a given technology. By the 1950's, the theorems of Arrow and De breu (1954) and McKenzie {1959) had formally demonstrated the existence of Pareto optimal competitive equilibria under certain conditions on individual preferences. The maintained assumption of neoclassical economics regard ing preference is that it is representable by a utility function and that it is private-regarding or "selfish". The first assumption implies that preference is both complete and fully transitive, in the sense that both strict preference ( P) and indifference (J) are transitive (thus for example if a: and yare indifferent as are y and z, then so are a: and z). The private-regarding assumption means that each individual, i, has a choice space, X;, say, on which i's preferences are defined. -

1 the Golden Age of Piracy HIUS 133 University of California, San Diego

The Golden Age of Piracy HIUS 133 University of California, San Diego Winter 2015 Professor Mark Hanna Mon., Wed., Fri.: 12:00-12:50 Office: H&SS #4059 Room: Solis 104 [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 1:15-3:00 This upper division lecture course is an interdisciplinary study of the Golden Age of piracy in the English speaking world. In his tale, The Water Witch (1830), James Fenimore Cooper noted two of the most enduring mythologies of early American history: “We have had our buccaneers on the water, and our witches on the land.” While the unfortunate women of Salem have been the subject of intense scholarly scrutiny, pirates remain on the margins of historical and literary studies. This course places pirates on center stage as a lens through which to study the massive transformations of the late sixteenth to the nineteenth century that marked the early phases of what is today called “globalization.” The rise and fall of global piracy correlated with a number of watershed events including the consolidation of the first British Empire, the integration of American colonial communities with global commerce, the formalization of international law, the rise of the novel, the first use of paper money in the Anglophone world, and the beginning of a local American press. This course introduces students to interdisciplinary studies and the use of primary sources. We will focus on a range of topics including global economics, international law, imperial politics, gender, literary studies, social class, journalism, and religion. Lastly, we will explore the construction of the Golden Age in historical memory in readings by James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe, Washington Irving, and Robert Louis Stevenson.