Appendix: Chronology of Pirate Plays in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East - West Laos Test of State Lottery Law ASBURY PARK — Nor Showdown Looms Man C

Weatfier Distribution Today Cloudy, with rain today, to. 17,800 night and tomorrow. High today, BEDBANK Mi. Low tonight near 40. High tomorrow, near St. Sea weathei 1 Independent Daily f page I. I HOUBAttHMXKIHHaDt.V-tSt.Ult J REGISTER SH 1-0010 Xnuad daily, Monday through Fridty. Second dm Puttgi • 7c PER COPY 35c PER WEEK VOL. 83, NO. 186 Paid lit R4d Buk and at Additional Malting Otticei. RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, MARCH 23,1961 BY CARRIER PAGE ONE Candidate Arrested on 'Request' Seeks Court East - West Laos Test of State Lottery Law ASBURY PARK — Nor Showdown Looms man C. Hansen, who seeks a Democratic nomination for the state Assembly on Joint Action ~a—platform advocating a U.S. Aid state lottery, had himself Is Mulled arrested here yesterday to fur- ther his cause. By SEATO The 42-year-old railroad station •gent from .Monmouth Beach, BANGKOK, Thailand after tipping off newspapers, walked into police headquarters, (AP)—Military advisers of presented the stub of a {3 Irish the Southeast Asia Treaty On Way Sweepstakes ticket to Desk Sgt, Organization kept hard at Thomas Flanagan, and said: "This belongs to me. It's a lot- work today on recommen- WASHINGTON (AP) — tery ticket. What do you propose dations for possible joint President Kennedy is ex- to do? actions to meet the Com- Flanagan, who had been tipped pected to make a major by newsmen to expect Hansen, munist threat in Laos. U.S. policy statement on was ready, "I'll have to book you The military leaders from the 1 the Laotian crisis today. -

Buddenbrooks (617) 536-4433 - 1 - [email protected] Voyages, Maritime and Pirates

Voyages, Maritime A CatalogueAnd featuring Pirates! More Than 30 Books BUDDENBROOKS (617) 536-4433 - 1 - [email protected] VOYAGES, MARITIME AND PIRATES Cover art is from item 29 To order please contact us by phone, fax or email, or online at buddenbrooks.com BUDDENBROOKS 21 Pleasant Street, On the Courtyard Newburyport, MA. 01950, USA (617) 536-4433 F: (978) 358-7805 [email protected] or [email protected] www.Buddenbrooks.com TERMS l Prices are net; postage and insurance are extra. l All books are offered subject to prior sale. l Bookplates and previous owners' signatures are not noted unless particularly obtrusive. l We respectfully request that payment be included with orders. l Massachusetts residents are requested to include 6.25% sales tax. l All books are returnable within ten days. We ask that you notify us by phone or fax in advance if you are returning a book. l We offer deferred billing to institutions in order to accomodate budgetary requirements. l Prices are subject to change without notice and we cannot be responsible for misprints or typographical errors. We invite you to search for books via our on-line listings at www.buddenbrooks. com. Please remember only a fraction of our inventory is listed at any time. If you are looking for something and you don't find it on-line, please call us to check our full listings or to take advantage of our Search Department. America's Award Winning Bookseller Buddenbrooks has one of the finest selections of fine and rare books in a number of fields, but we are happy to find any books, old or new, for our customers. -

Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan

` ASX: MYG Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan 4 August 2014 Highlights: • New management complete “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study, simplifying and optimising the Deflector Project • Mutiny Board has resolved to pursue financing and development of the Deflector project based on the new mine plan • New mine plan reduces open pit volume by 80% based on both rock properties and ore thickness, and establishes early access to the underground mine • Processing capital and throughput revised to align with optimal underground production rate of 380,000 tonnes per annum • Payable metal of 365,000 gold ounces, 325,000 silver ounces, and 15,000 copper tonnes • Pre-production capital of $67.6M • C1 cash cost of $549 per gold ounce • All in sustaining cost of $723 per gold ounce • Exploration review completed with primary focus to be placed on the 7km long, under explored, “Deflector Corridor” Note: Payable metal and costs presented in the highlights are taken from the Life of Mine Inventory model (LOM Inventory). All currency in AUS$ unless marked. Mutiny Gold Ltd (ASX:MYG) (“Mutiny” or “The Company”) is pleased to announce that the new company management, under the leadership of Managing Director Tony James, has completed an internal “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector gold, copper and silver project, located within the Murchison Region of Western Australia. The review was undertaken on detail associated with the 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) (ASX announcement 2 September, 2013). Tony James, -

Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin Mcdonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz

‘A Man of Courage and Activity’: Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin McDonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz “The sea is everything it is said to be: it provides unity, transport , the means of exchange and intercourse, if man is prepared to make an effort and pay a price.” – Fernand Braudel In the summer of 1694, Thomas Tew, an infamous Anglo -American pirate, was observed riding comfortably in the open coach of New York’s only six -horse carriage with Benjamin Fletcher, the colonel -governor of the colony. 2 Throughout the far -flung English empire, especially during the seventeenth century, associations between colonial administrators and pirates were de rig ueur, and in this regard , New York was similar to many of her sister colonies. In the developing Atlantic world, pirates were often commissioned as privateers and functioned both as a first line of defense against seaborne attack from imperial foes and as essential economic contributors in the oft -depressed colonies. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, moreover, colonial pirates and privateers became important transcultural brokers in the Indian Ocean region, spanning the globe to form an Indo-Atlantic trade network be tween North America and Madagascar. More than mere “pirates,” as they have traditionally been designated, these were early modern transcultural frontiersmen: in the process of shifting their theater of operations from the Caribbean to the rich trading grounds of the Indian Ocean world, 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the “Counter -Currents and Mainstreams in World History” conference at UCLA on December 6-7, 2003, organized by Richard von Glahn for the World History Workshop, a University of California Multi -Campus Research Unit. -

Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini</H1>

Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini Captain Blood, by Rafael Sabatini CAPTAIN BLOOD His Odyssey CONTENTS I. THE MESSENGER II. KIRKE'S DRAGOONS III. THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE IV. HUMAN MERCHANDISE V. ARABELLA BISHOP VI. PLANS OF ESCAPE VII. PIRATES VIII. SPANIARDS IX. THE REBELS-CONVICT X. DON DIEGO XI. FILIAL PIETY XII. DON PEDRO SANGRE page 1 / 543 XIII. TORTUGA XIV. LEVASSEUR'S HEROICS XV. THE RANSOM XVI. THE TRAP XVII. THE DUPES XVIII. THE MILAGROSA XIX. THE MEETING XX. THIEF AND PIRATE XXI. THE SERVICE OF KING JAMES XXIII. HOSTAGES XXIV. WAR XXV. THE SERVICE OF KING LOUIS XXVI. M. DE RIVAROL XXVII. CARTAGENA XXVIII. THE HONOUR OF M. DE RIVAROL XXIX. THE SERVICE OF KING WILLIAM XXX. THE LAST FIGHT OF THE ARABELLA XXXI. HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR CHAPTER I THE MESSENGER Peter Blood, bachelor of medicine and several other things besides, smoked a pipe and tended the geraniums boxed on the sill of his window above Water Lane in the town of Bridgewater. page 2 / 543 Sternly disapproving eyes considered him from a window opposite, but went disregarded. Mr. Blood's attention was divided between his task and the stream of humanity in the narrow street below; a stream which poured for the second time that day towards Castle Field, where earlier in the afternoon Ferguson, the Duke's chaplain, had preached a sermon containing more treason than divinity. These straggling, excited groups were mainly composed of men with green boughs in their hats and the most ludicrous of weapons in their hands. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Welcome from the Dais ……………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background Information ……………………………………………………………………… 3 The Golden Age of Piracy ……………………………………………………………… 3 A Pirate’s Life for Me …………………………………………………………………… 4 The True Pirates ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Pirate Values …………………………………………………………………………… 5 A History of Nassau ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Woodes Rogers ………………………………………………………………………… 8 Outline of Topics ……………………………………………………………………………… 9 Topic One: Fortification of Nassau …………………………………………………… 9 Topic Two: Expulsion of the British Threat …………………………………………… 9 Topic Three: Ensuring the Future of Piracy in the Caribbean ………………………… 10 Character Guides …………………………………………………………………………… 11 Committee Mechanics ……………………………………………………………………… 16 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………… 18 1 Welcome from the Dais Dear delegates, My name is Elizabeth Bobbitt, and it is my pleasure to be serving as your director for The Republic of Pirates committee. In this committee, we will be looking at the Golden Age of Piracy, a period of history that has captured the imaginations of writers and filmmakers for decades. People have long been enthralled by the swashbuckling tales of pirates, their fame multiplied by famous books and movies such as Treasure Island, Pirates of the Caribbean, and Peter Pan. But more often than not, these portrayals have been misrepresentations, leading to a multitude of inaccuracies regarding pirates and their lifestyle. This committee seeks to change this. In the late 1710s, nearly all pirates in the Caribbean operated out of the town of Nassau, on the Bahamian island of New Providence. From there, they ravaged shipping lanes and terrorized the Caribbean’s law-abiding citizens, striking fear even into the hearts of the world’s most powerful empires. Eventually, the British had enough, and sent a man to rectify the situation — Woodes Rogers. In just a short while, Rogers was able to oust most of the pirates from Nassau, converting it back into a lawful British colony. -

Repertory and Riot: the Relocation of Plays from the Red Bull to the Cockpit Stage

132 Issues in Review 28 Knutson, Playing Companies and Commerce, 62. 29 Leggatt, Jacobean Public Theatre, 4. Repertory and Riot: The Relocation of Plays from the Red Bull to the Cockpit Stage On 4 March 1617 the newly built Cockpit playhouse in Drury Lane was assailed by a band of ‘lewde and loose persons, apprentices and others’.1 Writ- ing four days after the event, Edward Sherbourne claimed that between three and four thousand apprentices had mobilized themselves, ‘wounded divers of the players, broke open their trunckes, & whatt apparreil, bookes, or other things they found, they burnt & cutt in peeces; & not content herewith, gott on the top of the house, & untiled it’.2 Consequences were not limited to loss of property. Sherbourne elaborates that ‘one prentise was slaine, being shott throughe the head with a pistoll, & many other of their fellowes were sore hurt’.3 On the same day, John Chamberlain wrote to Dudley Carleton of the disorder in town, adding that the players of Queen Anne’s Men, the current occupants of the Cockpit, ‘defended themselves as well as they could and slew three of them [the rioters] with shot, and hurt divers’.4 The gravity of the situation, at least as far as city authorities were concerned, is clear. In a letter to the lord mayor and aldermen of London, it was reported that ‘there were diverse people slayne, and others hurt and wounded’. Later that month, the privy council ordered security and vigilance against the behaviour of citizens and apprentices to be tightened.5 A number of historical narratives have prioritized the riot, which took place on Shrove Tuesday that year. -

Middle Years (6-9) 2625 Books

South Australia (https://www.education.sa.gov.au/) Department for Education Middle Years (6-9) 2625 books. Title Author Category Series Description Year Aus Level 10 Rules for Detectives MEEHAN, Adventure Kev and Boris' detective agency is on the 6 to 9 1 Kierin trail of a bushranger's hidden treasure. 100 Great Poems PARKER, Vic Poetry An all encompassing collection of favourite 6 to 9 0 poems from mainly the USA and England, including the Ballad of Reading Gaol, Sea... 1914 MASSON, Historical Australia's The Julian brothers yearn for careers as 6 to 9 1 Sophie Great journalists and the visit of the Austrian War Archduke Franz Ferdinand aÙords them the... 1915 MURPHY, Sally Historical Australia's Stan, a young teacher from rural Western 6 to 9 0 Great Australia at Gallipoli in 1915. His battalion War lands on that shore ready to... 1917 GARDINER, Historical Australia's Flying above the trenches during World 6 to 9 1 Kelly Great War One, Alex mapped what he saw, War gathering information for the troops below him.... 1918 GLEESON, Historical Australia's The story of Villers-Breteeneux is 6 to 9 1 Libby Great described as wwhen the Australians held War out against the Germans in the last years of... 20,000 Leagues Under VERNE, Jules Classics Indiana An expedition to destroy a terrifying sea 6 to 9 0 the Sea Illustrated monster becomes a mission involving a visit Classics to the sunken city of Atlantis... 200 Minutes of Danger HEATH, Jack Adventure Minutes Each book in this series consists of 10 short 6 to 9 1 of Danger stories each taking place in dangerous situations. -

“What Is That?” Off in the Dark, a Frightening, Glowing Shape Sailed Across the Ocean Like a Ghost

The moon shined down on the Windcatcher as the great clipper ship sailed through the cold waters of the southern Pacific Ocean. The year was 1849, and the Windcatcher was carrying passengers and cargo from San Francisco to New York City. The Windcatcher was one of the fastest ships on the seas. She was now sailing south, near Chile in South America. She would soon enter the dangerous waters near Cape Horn. Then she would sail into the Atlantic Ocean and move north to New York City. Suddenly, one of the sailors yelled to the crew. “Look!” he cried. “What is that?” Off in the dark, a frightening, glowing shape sailed across the ocean like a ghost. The captain and some of his men moved to the front of the ship to look. As soon as the captain saw the strange sight, he knew what it was. “The Flying Dutchman,” he said softly. The captain looked worried and lost in his thoughts. “What is the Flying Dutchman?” asked one of the sailors. 2 3 Pirates often captured the ships when the crew resisted, they Facts about Pirates and stole the cargo without were sometimes killed or left violence. Often, just seeing at sea with little food or water. the pirates’ flag and hearing Other times, the pirates took A pirate is a robber at sea who great deal of valuable cargo their cannons was enough to the crew as slaves, or the crew steals from other ships out being shipped across the make the crew of these ships became pirates themselves! at sea. -

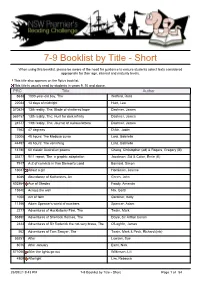

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short

7-9 Booklist by Title - Short When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title Author 5638 1000-year-old boy, The Welford, Ross 22034 13 days of midnight Hunt, Leo 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Dashner, James 569157 13th reality, The: Hunt for dark infinity Dashner, James 24577 13th reality, The: Journal of curious letters Dashner, James 7562 47 degrees D'Ath, Justin 23006 48 hours: The Medusa curse Lord, Gabrielle 44497 48 hours: The vanishing Lord, Gabrielle 14780 60 classic Australian poems Cheng, Christopher (ed) & Rogers, Gregory (ill) 33477 9/11 report, The: a graphic adaptation Jacobson, Sid & Colon, Ernie (ill) 7917 A-Z of convicts in Van Diemen's Land Barnard, Simon 16047 About a girl Horniman, Joanne 8086 Abundance of Katherines, An Green, John 602864 Ace of Shades Foody, Amanda 15540 Across the wall Nix, Garth 1058 Act of faith Gardiner, Kelly 11356 Adam Spencer's world of numbers Spencer, Adam 2277 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Twain, Mark 55890 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, The Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan 2444 Adventures of Sir Roderick the not-very brave, The O'Loghlin, James 562 Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark & Peck, Richard (intr) 55251 After Lawson, Sue 8076 After January Earls, Nick 571050 After the lights go out Wilkinson, Lili 4809 Afterlight Lim, -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Teacher's Book

Unit Strange but true! TEACHING TIP If students are not aware of what a preposition is, 4 you can easily explain that it is a word that usually comes before a noun or pronoun and expresses Lesson 1 a relation to another word, eg: ‘the man on the platform’, ‘the cat under the chair’, ‘they come Aims in winter’, etc. To learn and use prepositions of place to describe location. 3 Have students complete the sentences with the To read two articles about accidents with animals. prepositions in exercise 1. Check orally and write To use paratext and context to guess the meaning the answers on the board to avoid mistakes. of unknown words. Answers 1 out of; 2 into; 3 along; 4 through; 5 under; 6 down Initial phase Divide the class into two groups and invite a student PHASES EXTRA from group A to the front. Have this student spell out the past form of any verb – regular or irregular – for Students make sentences using the prepositions a student from group B to say the verb aloud and in orange to describe the pictures in exercise 1. make a sentence with it. If the second student says the verb correctly and makes an accurate sentence, 4 1.36 Write the word ’superstition’ on the board the group is awarded five points and this student and ask the class if they are superstitious or not goes out to the front to proceed in the same way and why. Also, ask what traditional superstitions with the opposite group. they know of: blackS.A.