The Flying Dutchman Dichotomy: the Ni Ternational Right to Leave V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan

` ASX: MYG Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan 4 August 2014 Highlights: • New management complete “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study, simplifying and optimising the Deflector Project • Mutiny Board has resolved to pursue financing and development of the Deflector project based on the new mine plan • New mine plan reduces open pit volume by 80% based on both rock properties and ore thickness, and establishes early access to the underground mine • Processing capital and throughput revised to align with optimal underground production rate of 380,000 tonnes per annum • Payable metal of 365,000 gold ounces, 325,000 silver ounces, and 15,000 copper tonnes • Pre-production capital of $67.6M • C1 cash cost of $549 per gold ounce • All in sustaining cost of $723 per gold ounce • Exploration review completed with primary focus to be placed on the 7km long, under explored, “Deflector Corridor” Note: Payable metal and costs presented in the highlights are taken from the Life of Mine Inventory model (LOM Inventory). All currency in AUS$ unless marked. Mutiny Gold Ltd (ASX:MYG) (“Mutiny” or “The Company”) is pleased to announce that the new company management, under the leadership of Managing Director Tony James, has completed an internal “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector gold, copper and silver project, located within the Murchison Region of Western Australia. The review was undertaken on detail associated with the 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) (ASX announcement 2 September, 2013). Tony James, -

“What Is That?” Off in the Dark, a Frightening, Glowing Shape Sailed Across the Ocean Like a Ghost

The moon shined down on the Windcatcher as the great clipper ship sailed through the cold waters of the southern Pacific Ocean. The year was 1849, and the Windcatcher was carrying passengers and cargo from San Francisco to New York City. The Windcatcher was one of the fastest ships on the seas. She was now sailing south, near Chile in South America. She would soon enter the dangerous waters near Cape Horn. Then she would sail into the Atlantic Ocean and move north to New York City. Suddenly, one of the sailors yelled to the crew. “Look!” he cried. “What is that?” Off in the dark, a frightening, glowing shape sailed across the ocean like a ghost. The captain and some of his men moved to the front of the ship to look. As soon as the captain saw the strange sight, he knew what it was. “The Flying Dutchman,” he said softly. The captain looked worried and lost in his thoughts. “What is the Flying Dutchman?” asked one of the sailors. 2 3 Pirates often captured the ships when the crew resisted, they Facts about Pirates and stole the cargo without were sometimes killed or left violence. Often, just seeing at sea with little food or water. the pirates’ flag and hearing Other times, the pirates took A pirate is a robber at sea who great deal of valuable cargo their cannons was enough to the crew as slaves, or the crew steals from other ships out being shipped across the make the crew of these ships became pirates themselves! at sea. -

Pandora-Eve-Ava: Albert Lewin's Making of a “Secret

PANDORA-EVE-AVA: ALBERT LEWIN’S MAKING OF A “SECRET GODDESS” Almut-Barbara Renger Introduction The myth of the primordial woman, the artificially fabricated Pandora, first related in the early Greek poetry of Hesiod, has proven extremely influential in the European history of culture, ideas, literature, and art from antiquity to the present day. Not only did the mythical figure itself undergo numerous refunctionalizations, but, in a striking manner, partic- ular elements of the narrative in the Theogony (Theogonia) and in Works and Days (Opera et dies) – for example, the jar, which would later be con- ceived as a box – also took on a life of their own and found their place in ever new cultural contexts. Having been drawn out from the “plot” (in the Aristotelian sense of μῦθος), these elements formed separate strands of reception that at times interfered with each other and at other times diverged. In the twentieth century such myth-elements also developed a distinc- tive dynamic of their own in film. Albert Lewin’s Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951) offers a particularly original conception of the Pandora myth by interweaving its elements with the legend of the Flying Dutch- man and plotting it into a story that takes place around 1930.1 It is the story of a young American woman, Pandora Reynolds, “bold and beautiful, desired by every man who met her” – so goes the original trailer of 1951, which opens with some introductory remarks about glamour by Hedda Hopper.2 Lewin’s intermingling of the Pandora myth and the Dutch legend in a love story of the 1950s is in many ways bold and original. -

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 bron The Low Countries. Jaargang 11. Stichting Ons Erfdeel, Rekkem 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_low001200301_01/colofon.php © 2011 dbnl i.s.m. 10 Always the Same H2O Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands hovers above the water, with a little help from her subjects, during the floods in Gelderland, 1926. Photo courtesy of Spaarnestad Fotoarchief. Luigem (West Flanders), 28 September 1918. Photo by Antony / © SOFAM Belgium 2003. The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 11 Foreword ριστον μν δωρ - Water is best. (Pindar) Water. There's too much of it, or too little. It's too salty, or too sweet. It wells up from the ground, carves itself a way through the land, and then it's called a river or a stream. It descends from the heavens in a variety of forms - as dew or hail, to mention just the extremes. And then, of course, there is the all-encompassing water which we call the sea, and which reminds us of the beginning of all things. The English once labelled the Netherlands across the North Sea ‘this indigested vomit of the sea’. But the Dutch went to work on that vomit, systematically and stubbornly: ‘... their tireless hands manufactured this land, / drained it and trained it and planed it and planned’ (James Brockway). As God's subcontractors they gradually became experts in living apart together. Look carefully at the first photo. The water has struck again. We're talking 1926. Gelderland. The small, stocky woman visiting the stricken province is Queen Wilhelmina. Without turning a hair she allows herself to be carried over the waters. -

Treasure Island

Treasure Island Contents: Afterschool Curriculum • Overview • 9 Sessions/Activities Thank you so much for your interest in this afterschool curriculum. • List of Local, State and This content is provided to you free of charge and was developed National Standards addressed for Beyond School Bells by Homegrown Theatre Camp • Treasure Island Script (homegrowntheatrecamp.org). Treasure Island: Overview Homegrown Theatre Camp for Beyond School Bells Program Outline: 9 Sessions Session 1 Casting & Read Through Session 2 Objectives Activity Session 3 Subtext Activity Session 4 Environment Walk Activity Session 5 Walk Like a Pirate Activity Session 6 Staging Rehearsal Session 7 Talk Like a Pirate Activity Session 8 Tech Day Crafts: Prepping for a Treasure Hunt Session 9 Dress Rehearsal Treasure Island S1 Casting & Read Through Set the Stage: Subtext in the Script | Treasure Island video: Beginning at 5:33 Activity 1: Cast Your Play Procedure: • Students should gather with their group of castmates. These groups will work together throughout the next few weeks, and can have anywhere from 1-4 students. ∙ Treasure Island Script • After viewing the synopsis in the video, students can discuss which ∙ Pencil characters they’d like to play. Ideas can be written down for discus- ∙ Paper sion within each cast group. ∙ Highlighters (if possible) • It’s possible that two students will want to play the same character, this is okay, an instructor can help them decide who can play what, with the understanding that each character has lines and plays a special part in the play. • Once characters are decided, a cast list for each group can be written down, and students can begin highlighting their lines in their scripts. -

C:\Myfiles\Genealogy & Family\Family Books\WW2 Timeline

A World War II Timeline A Perspective from within The Netherlands Compiled by Jo Kruithof - December 2004 01 12 April 1945 Canadian troops liberate the town of Steenwijk, where I was staying with my family at the time I was six years old then. A World War II Timeline a Perspective from within The Netherlands INTRODUCTION This document is based entirely on information and pictures found on the Internet. It is a brief illustrated timeline of the events of World War 2, as seen from within the Netherlands. When I first came across a basic timeline on the (Dutch) web site http://hetillegaleparool.nl, it occurred to me that, if I ever got around to writing up my life’s story, this would paint a good picture of the background against which I lived my first six years. However, before it would be any use to my descendants, I would either have to translate it, or find an alternative in the English language. Any writings presenting the unique view of the war by Dutch people living in the Netherlands is much more likely to be in Dutch than in English (and a quick scan of the Net supported this notion), so I decided on the translation option. In the process of checking out a few facts, events and names, I came across large amounts of other material, but I have only used those bits and pieces that helped to flesh out my timeline into a record that can be read and understood by those who weren’t there or who haven’t heard the stories from parents or older relatives. -

Gulliver's Travels" Author(S): John Robert Moore Source: the Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol

The Geography of "Gulliver's Travels" Author(s): John Robert Moore Source: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Apr., 1941), pp. 214-228 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27704741 Accessed: 17-01-2020 16:44 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of English and Germanic Philology This content downloaded from 117.240.50.232 on Fri, 17 Jan 2020 16:44:37 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms THE GEOGRAPHY OF GULLIVER'S TRAVELS I It is a commonplace that Gulliver's Travels is patterned after the real voyages of Swift's age, which it either travesties or imi tates. It lacks the supplement, describing the flora and fauna, so often appended to voyages; but it has the connecting links of detailed narrative, the solemn spirit of inquiry into strange lands, the factual records of latitude and coasts and prevailing winds, and (most of all) the maps. I have no quarrel with the present-day emphasis upon the philosophical background of Gulliver's Travels; that is a charac teristic contribution of the scholars of our generation. -

Pirates of the Caribbean – at World's

LEVEL 3 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme Pirates of the Caribbean – At World’s End to the other world and became committed to hunting EASYSTARTS pirates. Tia Dalma: A mysterious woman who can see into the future and bring people back from the dead. She is really LEVEL 2 Calypso in human form. Sao Feng: A very important Pirate Lord of Singapore. He helps Barbossa, Elizabeth and Will find their way to the LEVEL 3 land of the dead to rescue Jack Sparrow. He believes that Elizabeth is the goddess Calypso in human shape. Bootstrap Bill: Will Turner’s father. He is very loyal to LEVEL 4 the Dutchman’s crew and even attacks his own son when Based on the characters created by Ted Elliot, Terry Rossio, he jumps on board to help Jack. Stuart Beattie and Jay Wolpert. LEVEL 5 Written by Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio. Summary Based on Walt Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean. The letter: The book starts with a letter from Admiral Produced by Jerry Bruckheimer. Brutton which outlines what has happened in the past LEVEL 6 Directed by Gore Verbinski. to all the characters we are going to meet in the book, and which states that Jack Sparrow, a pirate, is a very Character description dangerous man. Captain Jack Sparrow: The central character. He is a very Chapters 1–3: Three pirate ships are attacked by cunning man who always manages to escape from difficult the Flying Dutchman and many pirates are killed. The situations. At the beginning of the book, he is rescued Dutchman’s captain is Davy Jones. -

The Flying Dutchman Wagner TABLE of CONTENTS

PRESENTS The Flying Dutchman Wagner TABLE OF CONTENTS The Flying Dutchman Wagner WELCOME ....................................................................................................................................3 PRE-PERFORMANCE Activities Preparing Students for the Opera ...................... 4 CREDITS .........................................................................................................................................6 CHARACTER MAP Who’s Connected How .......................................................................7 SYNOPSIS What’s the Opera About? .................................................................................8 PRODUCTION NOTE In Depth Look at Dutchman ......................................................10 WAGNER About the Composer ......................................................................................... 12 CAST & CREATIVE Who’s Who? .........................................................................................8 SPOTLIGHT Richard Brady - Bass Trombone ................................................................ 19 BACKGROUND About Leitmotif .......................................................................................20 LEITMOTIF Activity .................................................................................................................. 21 OPERA 101 The Basics ........................................................................................................... 22 OPERA 101 Different Styles of Opera .............................................................................. -

Complete Scenery Information for Select Plays

The Miami University Libraries The Walter Havighurst Special Collections Oxford, OH 45056 ENGLISH TOY THEATRE COLLECTION Finding Aid: Complete Scenery Information for Select Plays Battle of Waterloo – Black & White – Green – Various (6/12 plates) 5: Maid and the Magpie, back of Sc. 1, No. 2 Battle of Waterloo, Sc. 5, No. 5 Robert Macaire, back of Sc. 1 & 2, No. 2 Sixteen String Jack, Sc. 5, No. 5 (Pub. J.K. Green, Feb. 15, 1836, sold by J. Redington) 6: Battle of Waterloo, Sc. 6, No. 6 (Pub. J.K. Green, June 18, 1842, sold by J. Redington) 7: Battle of Waterloo, Sc. 8, No. 7 (Pub. J.K. Green, June 18, 1842, sold by J. Redington) 8: Battle of Waterloo, Sc. 9, No. 8 (Pub. J.K. Green, June 18, 1842, sold by J. Redington) 9: Life of a Soldier, Sc. 2 & 18, No. 2 Tom Thumb, Sc. 8 and 11, No. 6 Battle of Waterloo, Sc. 10, No. 9 Richard the Third, Sc. 19 & 21, No. 15 (Pub. J.K. Green, June 18, 1842, sold by J. Redington) 10: Children in the Wood, Sc. 10, No. 8 Battle of Waterloo, Sc. 11, No. 10 Wapping Old Stairs, Sc. 1, 6 & 12, No. 1 Sixteen String Jack, Sc. 12, No.10 (Pub. J.K. Green, Feb. 1, 1838, sold by J. Redington) Battle of Waterloo – Color – Green – Various (6/12 plates) 5: Maid and the Magpie, back of Sc. 1, No. 2 Battle of Waterloo, Sc. 5, No. 5 Robert Macaire, back of Sc. 1 & 2, No. 2 Sixteen String Jack, Sc. -

THE USAGE of SIGN AS SEEN on PIRATES of the CARIBBEAN: DEAD MEN TELL NO TALES FILM PRODUCED by JERRY BUCKHEIMER THESIS Submitte

THE USAGE OF SIGN AS SEEN ON PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: DEAD MEN TELL NO TALES FILM PRODUCED BY JERRY BUCKHEIMER THESIS Submitted to the Board Examination In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For Literary Degree at English Literature Department by ANNISA RULIANA NIM: AI.140217 ENGLISH LITERATURE DEPARTMENT ADAB AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SULTAN THAHA SAIFUDDIN JAMBI 2019 DEDICATION First of all I would say the grateful to Allah SWT always gives me health to finish this thesis. I would like to dedicate this thesis to: My beloved Father, Khairulzar for your love, supporting and praying My beloved Mother, Agustina for all your patients to educate me so far, gave me a way to be the student, for your love, supporting and praying And My beloved Young Sister Kartika Ayunda also for your supporting and praying. All of you are my diamond who Allah has given to me. I do really want to make you are happy and proud of me! For My Special Sister Almh. Wilda Mazni who has in heaven, thank you because her gave encouragement, support and praying, I hope she proud of me there. For My lovely Sister Juraidah who always make me laugh and her kindness, support and praying. For My supervisor, Mrs. Tira Mariana and Mr. Mislan who has guided, and continues to provide me support so that this thesis is resolved. And My friend Pina Pitria Thanks for the advice, love, help, support, ideas and great experiences that we have made together. And also My love Mardi Wijaya for the care, love, and support you provided while I was writing this thesis All you are the good example for me. -

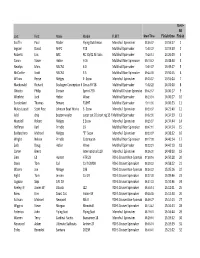

Last First Make Model FLEET Scoffin Paul Mader Flying Dutchman

Over- All Last First Make Model FLEET Start Time Finish time Finish Scoffin Paul Mader Flying Dutchman Monohull Spinnaker 08:55:07 13:16:27 1 Ingram David AHPC F18 Multihull Spinnaker 10:02:22 13:19:39 2 Roberts Eric ARC RC 30/41 All Sails Multihull Spinnaker 10:28:13 13:26:09 3 Caron Steve Hobie H16 Multihull Non Spinnaker 09:10:42 13:48:40 4 Newlyn Marc NACRA 6.0 Multihull Spinnaker 10:01:37 13:49:27 5 McCorkle Scott NACRA 5.5 Multihull Non Spinnaker 09:44:08 13:50:55 6 Wilkins Reese Melges E‐ Scow Monohull Spinnaker 09:23:37 13:55:04 7 Macdonald Richard Boulogne Conception MCirrus R F18 Multihull Spinnaker 10:02:22 14:03:00 8 Ghiotto Philip Corsair Sprint 750 Multihull Cruiser Spinnaker 09:42:37 14:06:17 9 Woehrle Jack Hobie Wave Multihull Spinnaker 08:23:31 14:06:27 10 Sunderland Thomas Bimare F18HT Multihull Spinnaker 10:11:30 14:06:53 11 Myles Loesel Scott Rice Johnson Boat Works E‐ Scow Monohull Spinnaker 09:23:37 14:21:40 12 laibl chip boston wayler super cat 20 short rig 33 f Multihull Spinnaker 09:52:30 14:34:39 13 Mundell Robert Melges E Scow Monohull Spinnaker 09:23:37 14:34:44 14 Hoffman Karl Prindle 19 Multihull Non Spinnaker 09:47:10 14:34:54 15 Baldacchino Michael Melges "E" Scow Monohull Spinnaker 09:23:37 14:38:32 16 Wright Nelson Prindle Catamaran Multihull Non Spinnaker 09:17:09 14:40:14 17 Seib Doug Hobie Wave Multihull Spinnaker 08:23:31 14:42:19 18 Carter Brent International 110 Monohull Spinnaker 08:36:30 14:48:00 19 Sims Ed Hunter HTR 23 RCHS Cruiser Non‐Spinnake 07:50:16 14:50:28 20 Davis Tom Cal Cal 9.2MDK RCHS Cruiser Spinnaker 08:39:32 14:58:22 21 Waters Joe Mirage 236 RCHS Cruiser Non‐Spinnake 08:34:32 15:05:16 22 Kight Tom Jensen Cal 29 RCHS Cruiser Spinnaker 08:27:38 15:09:46 23 Lagasse Skip CAL 29 RCHS Cruiser Spinnaker 08:31:33 15:10:46 24 Keeley, III James W.