The Influence of Sea Shanties on Classical Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016 Welcome to the Junk Rig Glossary! The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) is a Member Project of the Junk Rig Association, initiated by Bruce Weller who, as a then new member, found that he needed a junk 'dictionary’. The aim is to create a comprehensive and fully inclusive glossary of all terms pertaining to junk rig, its implementation and characteristics. It is intended to benefit all who are interested in junk rig, its history and on-going development. A goal of the JRG Project is to encourage a standard vocabulary to assist clarity of expression and understanding. Thus, where competing terms are in common use, one has generally been selected as standard (please see Glossary Conventions: Standard Versus Non-Standard Terms, below) This is in no way intended to impugn non-standard terms or those who favour them. Standard usage is voluntary, and such designations are wide open to review and change. Where possible, terminology established by Hasler and McLeod in Practical Junk Rig has been preferred. Where innovators have developed a planform and associated rigging, their terminology for innovative features is preferred. Otherwise, standards are educed, insofar as possible, from common usage in other publications and online discussion. Your participation in JRG content is warmly welcomed. Comments, suggestions and/or corrections may be submitted to [email protected], or via related fora. Thank you for using this resource! The Editors: Dave Zeiger Bruce Weller Lesley Verbrugge Shemaya Laurel Contents Some sections are not yet completed. ∙ Common Terms ∙ Common Junk Rigs ∙ Handy references Common Acronyms Formulae and Ratios Fabric materials Rope materials ∙ ∙ Glossary Conventions Participation and Feedback Standard vs. -

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan

` ASX: MYG Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan 4 August 2014 Highlights: • New management complete “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study, simplifying and optimising the Deflector Project • Mutiny Board has resolved to pursue financing and development of the Deflector project based on the new mine plan • New mine plan reduces open pit volume by 80% based on both rock properties and ore thickness, and establishes early access to the underground mine • Processing capital and throughput revised to align with optimal underground production rate of 380,000 tonnes per annum • Payable metal of 365,000 gold ounces, 325,000 silver ounces, and 15,000 copper tonnes • Pre-production capital of $67.6M • C1 cash cost of $549 per gold ounce • All in sustaining cost of $723 per gold ounce • Exploration review completed with primary focus to be placed on the 7km long, under explored, “Deflector Corridor” Note: Payable metal and costs presented in the highlights are taken from the Life of Mine Inventory model (LOM Inventory). All currency in AUS$ unless marked. Mutiny Gold Ltd (ASX:MYG) (“Mutiny” or “The Company”) is pleased to announce that the new company management, under the leadership of Managing Director Tony James, has completed an internal “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector gold, copper and silver project, located within the Murchison Region of Western Australia. The review was undertaken on detail associated with the 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) (ASX announcement 2 September, 2013). Tony James, -

The Timelessness of the King's Busketeers: a Splash Into Sea

The Timelessness of The King’s Busketeers: A splash into sea shanties Sea Shanties are typically not my preferred listening, but my recent research into the genre as a whole has yielded some fascinating results. Long before TikTok made it trending, The King’s Busketeers – Joshua Gannon-Salomon, Andrew Prete, and Sam Atwood – were continuing the traditions of many sailors before them hundreds of years in the making. The King’s Busketeers are carrying these traditions forward with their traditional, yet updated sound. Joshua provided a bit of additional context for their work: “One thing the sea shanty trend has demonstrated clearly, is that folk music is not a genre but a process. Shantymen in the days of sail were constantly rehashing old songs into new, taking inspiration anywhere a good rhythm for hauling or working the capstan could be found.” Joshua spoke of the interesting time of history we’re in that mirrors the old world into which the shanty genre was born: “Many articles have pointed out interesting parallels between modern shanty fans under pandemic conditions and the confined, monotonous, overworked and precarious lives of the sailors who sang them. We have comforts they never dreamed of, and their work was intensely social rather than isolated, but suddenly many more people feel solidarity with the sailors of old, their exploitation at the hands of captains and empires, and their lust for life in spite of it. If COVID-19 is today’s stormy voyage, then our visions of post-pandemic celebration parallel the sailors’ dreams of the bars and bawdy houses in the next port.” That might be why shanties are having the cultural moment that they are. -

An Afternoon at the Proms 24 March 2018

AN AFTERNOON AT THE PROMS 24 MARCH 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM MELBOURNE SIR ANDREW DAVIS TASMIN SYMPHONY LITTLE ORCHESTRA Courtesy B Ealovega Established in 1906, the Chief Conductor of the Tasmin Little has performed Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Melbourne Symphony Melbourne Symphony in prestigious venues Sir Andrew Davis conductor Orchestra (MSO) is an Orchestra, Sir Andrew such as Carnegie Hall, the arts leader and Australia’s Davis is also Music Director Concertgebouw, Barbican Tasmin Little violin longest-running professional and Principal Conductor of Centre and Suntory Hall. orchestra. Chief Conductor the Lyric Opera of Chicago. Her career encompasses Sir Andrew Davis has been He is Conductor Laureate performances, masterclasses, Elgar In London Town at the helm of MSO since of both the BBC Symphony workshops and community 2013. Engaging more than Orchestra and the Toronto outreach work. Vaughan Williams The Lark Ascending 3 million people each year, Symphony, where he has Already this year she has the MSO reaches a variety also been named interim Vaughan Williams English Folksong Suite appeared as soloist and of audiences through live Artistic Director until 2020. in recital around the UK. performances, recordings, Britten Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra In a career spanning more Recordings include Elgar’s TV and radio broadcasts than 40 years he has Violin Concerto with Sir Wood Fantasia on British Sea Songs and live streaming. conducted virtually all the Andrew Davis and the Royal Elgar Pomp and Circumstance March No.1 Sir Andrew Davis gave his world’s major orchestras National Scottish Orchestra inaugural concerts as the and opera companies, and (Critic’s Choice Award in MSO’s Chief Conductor in at the major festivals. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

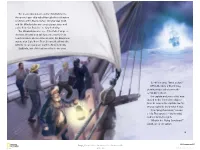

“What Is That?” Off in the Dark, a Frightening, Glowing Shape Sailed Across the Ocean Like a Ghost

The moon shined down on the Windcatcher as the great clipper ship sailed through the cold waters of the southern Pacific Ocean. The year was 1849, and the Windcatcher was carrying passengers and cargo from San Francisco to New York City. The Windcatcher was one of the fastest ships on the seas. She was now sailing south, near Chile in South America. She would soon enter the dangerous waters near Cape Horn. Then she would sail into the Atlantic Ocean and move north to New York City. Suddenly, one of the sailors yelled to the crew. “Look!” he cried. “What is that?” Off in the dark, a frightening, glowing shape sailed across the ocean like a ghost. The captain and some of his men moved to the front of the ship to look. As soon as the captain saw the strange sight, he knew what it was. “The Flying Dutchman,” he said softly. The captain looked worried and lost in his thoughts. “What is the Flying Dutchman?” asked one of the sailors. 2 3 Pirates often captured the ships when the crew resisted, they Facts about Pirates and stole the cargo without were sometimes killed or left violence. Often, just seeing at sea with little food or water. the pirates’ flag and hearing Other times, the pirates took A pirate is a robber at sea who great deal of valuable cargo their cannons was enough to the crew as slaves, or the crew steals from other ships out being shipped across the make the crew of these ships became pirates themselves! at sea. -

Unit Will Provide a Way to Connect Science Through Aquatic Organisms and Human Endeavors, Historically and Musically

Songs of the Sea, Above and Below Laurie Bailey Introduction Sea shanties are a part of our musical and nautical history. Shanties provided a strong beat for sailors to work in unison. They described the adventures and trials of sailors and entertained sailors who sailed the seas for up to four years at a time. Shanties tend to be “catchy” and therefore easily learned. In addition, they were written in prose easily understood by those with little education1. To our benefit, shanties provide a type of historical record of sea life in the 18th and 19th centuries. Shanties usually have many verses but almost always include a chorus when all the sailors can sing together. I think this will be a useful tool to help my students participate in singing the shanties. Discussing whales and their communication skills will be a great way to talk to my students about how singing is a way of communication for them and for humans. This unit will provide a way to connect science through aquatic organisms and human endeavors, historically and musically. Rationale Castle Hills Elementary School, located on Moores Lane in New Castle, Delaware, is a school for students in Kindergarten through fifth grade. Enrollment during the school year 2014-2015 was 658. Slightly over one third of the population is African American. Slightly under one third is white and 26% of the students are Hispanic. Just over half of the student population is considered to be Low Income with about 17% who speak another language at home. Fewer than 10% of the students have special needs.2 As I write this paper, this is to be my fourth week at the school, having been reassigned from a school with a population of students with severe physical and cognitive disabilities. -

The Flying Dutchman Dichotomy: the Ni Ternational Right to Leave V

Penn State International Law Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 2 Dickinson Journal of International Law 1991 The lF ying Dutchman Dichotomy: The International Right to Leave v. The oS vereign Right to Exclude Suzanne McGrath Dale Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Dale, Suzanne McGrath (1991) "The Flying Dutchman Dichotomy: The nI ternational Right to Leave v. The oS vereign Right to Exclude," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 9: No. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol9/iss2/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Flying Dutchman Dichotomy: The International Right to Leave v. The Sovereign Right to Exclude' I. Introduction The Flying Dutchman is a mythic figure who is condemned to roam the world, never resting, never bringing his ship to port, until Judgement Day. Cursed by past crimes, he is forbidden to land and sails from sea to sea, seeking a peace which forever eludes him. The Dutchman created his own destiny. His acts caused his curse. He is ruled by Fate, not man-made law, or custom, or usage. But today, thanks to man's laws and man's ideas of what should be, there are many like the Dutchman who can find no port, no place to land. -

INTRODUCTION the Arrangements

5 INTRODUCTION Welcome to The Language of Folk 1. This book is meant as an introduction to the world of folk song and is no more than a drop in the ocean in terms of the range of song types, subject matter, melodies and vocal styles found in folk music. The majority of the songs in this collection have their origins in the British Isles, though one or two come from America or further afield. This book brings together songs from different ages. Many are very old, although in some cases they cannot easily be traced further back than the the folk music revivals of the 1920s or 1950s–60s. Folk song, however, is a living tradition, so this book also includes modern songs that have been assimilated into the folk music tradition in recent years; although not ‘traditional’ in the usual sense, they have been included here because they are fantastic to sing and would happily sit in any folk singer’s repertoire. Musicians and audiences often refer to ‘the folk music community’ when talking about the music in its modern setting. There are thousands of people singing, playing, dancing to and listening to this music, and these people form an active community with shared interests. The music is inclusive, so those new to the folk tradition are encouraged and welcomed. ‘Sing-a-rounds’ and ‘sessions’ are commonplace within the UK and Ireland; these are situations (often in a pub or in someone’s home) where anyone is welcomed to sing and play music together. The intention is to share, not to perform, and they are a fantastic setting in which to try out new songs. -

Pandora-Eve-Ava: Albert Lewin's Making of a “Secret

PANDORA-EVE-AVA: ALBERT LEWIN’S MAKING OF A “SECRET GODDESS” Almut-Barbara Renger Introduction The myth of the primordial woman, the artificially fabricated Pandora, first related in the early Greek poetry of Hesiod, has proven extremely influential in the European history of culture, ideas, literature, and art from antiquity to the present day. Not only did the mythical figure itself undergo numerous refunctionalizations, but, in a striking manner, partic- ular elements of the narrative in the Theogony (Theogonia) and in Works and Days (Opera et dies) – for example, the jar, which would later be con- ceived as a box – also took on a life of their own and found their place in ever new cultural contexts. Having been drawn out from the “plot” (in the Aristotelian sense of μῦθος), these elements formed separate strands of reception that at times interfered with each other and at other times diverged. In the twentieth century such myth-elements also developed a distinc- tive dynamic of their own in film. Albert Lewin’s Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951) offers a particularly original conception of the Pandora myth by interweaving its elements with the legend of the Flying Dutch- man and plotting it into a story that takes place around 1930.1 It is the story of a young American woman, Pandora Reynolds, “bold and beautiful, desired by every man who met her” – so goes the original trailer of 1951, which opens with some introductory remarks about glamour by Hedda Hopper.2 Lewin’s intermingling of the Pandora myth and the Dutch legend in a love story of the 1950s is in many ways bold and original. -

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11

The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 bron The Low Countries. Jaargang 11. Stichting Ons Erfdeel, Rekkem 2003 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_low001200301_01/colofon.php © 2011 dbnl i.s.m. 10 Always the Same H2O Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands hovers above the water, with a little help from her subjects, during the floods in Gelderland, 1926. Photo courtesy of Spaarnestad Fotoarchief. Luigem (West Flanders), 28 September 1918. Photo by Antony / © SOFAM Belgium 2003. The Low Countries. Jaargang 11 11 Foreword ριστον μν δωρ - Water is best. (Pindar) Water. There's too much of it, or too little. It's too salty, or too sweet. It wells up from the ground, carves itself a way through the land, and then it's called a river or a stream. It descends from the heavens in a variety of forms - as dew or hail, to mention just the extremes. And then, of course, there is the all-encompassing water which we call the sea, and which reminds us of the beginning of all things. The English once labelled the Netherlands across the North Sea ‘this indigested vomit of the sea’. But the Dutch went to work on that vomit, systematically and stubbornly: ‘... their tireless hands manufactured this land, / drained it and trained it and planed it and planned’ (James Brockway). As God's subcontractors they gradually became experts in living apart together. Look carefully at the first photo. The water has struck again. We're talking 1926. Gelderland. The small, stocky woman visiting the stricken province is Queen Wilhelmina. Without turning a hair she allows herself to be carried over the waters.