A Unique Recording of "The Leaving of Liverpool"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Moore, Whose Patri- Manuscript Facsimiles and Musical Files, Otic-Imbued Writings Earned Him the with Commentary,” He Said

cc Page 24 Echo Lifestyle Ireland’s Minstrel Boy gets his encore By Michael P. Quinlin [email protected] William Blake. Phase one of the Moore project is slat- BOSTON — Ireland’s first mega star ed to go live this November, when the wrote poetry, history tomes and political Hypermedia Archive will be launched polemics that made him the talk of the at a conference in Galway, according to town in his native Dublin as well as in Ryder. London, Boston and New York. “By next year, we should have all the We’re not talking about Bono here, ‘Irish Melodies’ available online as texts, but rather Thomas Moore, whose patri- manuscript facsimiles and musical files, otic-imbued writings earned him the with commentary,” he said. The interest in Moore is enhanced by www.irishecho.com / Irish Echo May 21-27, 2008 titles Bard of Erin and Ireland’s National Poet. two new biographies, including one It was Moore’s lyrics to ancient Irish published last month by Ronan Kelly airs that brought him fame and notoriety entitled, “The Bard of Erin: the Life of during his lifetime and beyond. His Thomas Moore,” which Ryder says is famous collection, “Moore’s Melodies,” superb. was admired by the likes of Beethoven Like Ryder, Professor Flannery in and Lord Byron, and translated into six Atlanta never lost faith in Moore’s languages. importance in Irish history as a song- “Moore’s Melodies” was a ten-vol- writer, a literary influence and a nation- ume set of 124 songs published between alist figure. -

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

The American Voice Anthology of Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky University of Kentucky UKnowledge Creative Writing Arts and Humanities 1998 The American Voice Anthology of Poetry Frederick Smock Bellarmine College Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Smock, Frederick, "The American Voice Anthology of Poetry" (1998). Creative Writing. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_creative_writing/3 vice ANTHOLOGY OF POETRY EDITED BY FREDERICK SMOCK THE UNIVEESITT PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the Kentucky Foundation for Women, Inc., and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1998 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The American Voice anthology of poetry / edited by Frederick Smock. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

(Tom) of Granada Hills, CA Passed Away on December 15, 2009 from Complications of Ovarian Cancer Surgery

Home About Calendar/News Gallery Green Pages Contact 2009 OBITUARIES December Joan May Manning, beloved wife of Thomas F Manning (Tom) of Granada Hills, CA passed away on December 15, 2009 from complications of ovarian cancer surgery. Joan was a Londoner by birth, but a Yankee at heart, coming to America in 1956 with her husband Tom. She was an active member of the Burbank clubs (Moose, VFW, American Legion) and a talented singer who entertained many of us over the years with her lovely voice. She is survived by her loving daughters Chris O'Shaunnessy of Sunland CA, Mary Schumacher of Denver, CO and Shelagh Manning of Towanda, PA and by her many beautiful grandchildren and great grandchildren. Patrick J. Kane was born on 21st October 1933 in Bray, Co Wicklow and passed on 16th December 2009 in Loughlinstown Hospital, Co Wicklow. Patrick and his wife Brenda came here in 1963. They joined St Therese Parish in Alhambra. Their six children all graduated from the parish school. The Kane's maintained a home in Co Wicklow. While Pat was in Ireland in December 2009 he became ill. After much persuasion from the family "Poppers" agreed to be checked out at the Loughlinstown Hospital. He was diagnosed --" a severe case of pneumonia". Pat had left it too late. He wanted to see his own doctor here in California. Alas, Pat did not make that scheduled flight on 10th January 2010. Most of the family live in Ireland but Pat waited till son Ed arrived from Kentucky and son Mike from Valencia and Deirdre from Temple City. -

Songs by Artist

DJ Song list Songs by Artist DJ Song list Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions -- 360 Ft Pez 50 Cent Adam & The Ants Al Green -- 360 Ft Pez - Live It Up DJ 21 Questions DJ Ant Music DJ Let's Stay Together We -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne Candy Shop DJ Goody Two Shoes DJ Al Stuart -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne - DJ Hustler's Ambition DJ Stand And Deliver DJ Year Of The Cat DJ Loyal If I Can't DJ Adam Clayton & Larry Mullen Alan Jackson -- Illy In Da Club DJ Theme From Mission DJ Hi Chattahoochee DJ -- Illy - Tightrope (Clean) DJ Just A Li'l Bit DJ Impossible Don't Rock The Jukebox DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog 50 Cent Feat Justin Timberlake Adam Faith Gone Country DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog DJ Ayo Technology DJ Poor Me DJ Livin' On Love DJ - Wiggle 50 Cent Feat Mobb Deep Adam Lambert Alan Parsons Project -- Th Amity Afflication Outta Control DJ Adam Lambert - Better Than I DJ Eye In The Sky 2010 Remix DJ -- Th Amity Afflication - Dont DJ Know Myself 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam Levin Alanis Morissette Lean On Me(Warning) If I Had You DJ 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam DJ Hand In My Pocket DJ - The Potbelleez Whataya Want From Me Ch Levine - My Life (Edited) Ironic DJ Shake It - The Potbelleez DJ Adam Sandler 50Cent Feat Ne-Yo You Oughta Know DJ (Beyonce V Eurythmics Remix (The Wedding Singer) I DJ Baby By Me DJ Alannah Myles Sweet Dreams DJ Wanna Grow Old With You 60 Ft Gossling Black Velvet DJ 01 - Count On Me - Bruno Marrs Adele 360 Ft Gossling - Price Of DJ Albert Lennard Count On Me - Bruno Marrs DJ Fame Adele - Skyfall DJ Springtime In L.A. -

The Timelessness of the King's Busketeers: a Splash Into Sea

The Timelessness of The King’s Busketeers: A splash into sea shanties Sea Shanties are typically not my preferred listening, but my recent research into the genre as a whole has yielded some fascinating results. Long before TikTok made it trending, The King’s Busketeers – Joshua Gannon-Salomon, Andrew Prete, and Sam Atwood – were continuing the traditions of many sailors before them hundreds of years in the making. The King’s Busketeers are carrying these traditions forward with their traditional, yet updated sound. Joshua provided a bit of additional context for their work: “One thing the sea shanty trend has demonstrated clearly, is that folk music is not a genre but a process. Shantymen in the days of sail were constantly rehashing old songs into new, taking inspiration anywhere a good rhythm for hauling or working the capstan could be found.” Joshua spoke of the interesting time of history we’re in that mirrors the old world into which the shanty genre was born: “Many articles have pointed out interesting parallels between modern shanty fans under pandemic conditions and the confined, monotonous, overworked and precarious lives of the sailors who sang them. We have comforts they never dreamed of, and their work was intensely social rather than isolated, but suddenly many more people feel solidarity with the sailors of old, their exploitation at the hands of captains and empires, and their lust for life in spite of it. If COVID-19 is today’s stormy voyage, then our visions of post-pandemic celebration parallel the sailors’ dreams of the bars and bawdy houses in the next port.” That might be why shanties are having the cultural moment that they are. -

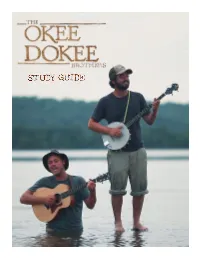

Okeedokeestudyguide2016.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Who Are The Okee Dokee Brothers?.................................................................................................................................1 What Kind of Music Do They Play?.................................................................................................................................2 Down the Mississippi River...............................................................................................................................................3 On the Appalachian Trail..................................................................................................................................................4 Along the Great Divide.....................................................................................................................................................5 Instruments in the Show: Strings.......................................................................................................................................6 Instruments in the Show: Percussion..................................................................................................................................7 Before the Performance.....................................................................................................................................................8 After the Performance.......................................................................................................................................................9 Okee Dokee Vocab..........................................................................................................................................................10 -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

MUSIC of IRELAND Fact Sheet PRESS FINAL

Premiering nationwide March 2010 on public television (check local listings), Music of Ireland – DVD plus exclusive Welcome Home tells the definitive story of bonus CD available contemporary Irish music, starting in 1960 with the only through public Clancy Brothers. Grammy-winner Moya Brennan television stations! (Clannad) hosts this new documentary featuring exclusive interviews and performances from The Chieftains’ Paddy Moloney , Riverdance ’s Michael Flatley & Bill Whelan , U2’s Bono & Adam Clayton , Sinéad O’Connor , Bob Geldof , Pete Seeger , The Dubliners’ John Sheahan , the late Liam Clancy ’s last interview before his death (12/2009), and other great icons of Irish popular culture. See vintage clips of The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem on The Ed Sullivan Show, Judy Collins playing music from the ‘old Companion CD of new & original country,’ The Pogues and Van Morrison with The songs from artists Chieftains on RTE’s “Late, Late Show,” Riverdance ’s in the program and debut at Eurovision and more! A must-see for music other Irish music fans, Music of Ireland explores the impact of Irish stars! music in America and the world. Preview video and more at wliw.org/musicofireland . Media Kit : wliw.org/pressroom Media Contacts Natasha Padilla Patti Conte Melani Rogers WNET.ORG Plan A Media Plan A Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 212.560.8824 Phone: 212.337.1406 ext 16 Phone: 212.337.1406 ext 18 The greatest Irish musical artists of our time in the definitive story of contemporary Irish music -

Newsletter They Put on a Great Show and Hopefully We Can Get Them Back Next Year

Thank you again for those who have supported this campaign and in advance day and to all who helped in any way. The next one is sure to be even bigger. to our remaining members for your anticipated generous support. Thank you to all who came and supported the recent concert with The Druids. Newsletter They put on a great show and hopefully we can get them back next year. Irish American Community Center If you need additional information and/or have questions please contact any Congratulations to this year’s Woman of the Year, Wendy Mackey and to Man member of the executive board or any of the following capital improvement of the Year, Ed Donadio. They are two excellent choices. I hope you both have New Haven Gaelic Football & Hurling Club campaign committee members: Donna Borzillo, Sean Cox, John Cullinan, a great night at the banquet in November. Hope to see many of you at the Michael Faherty, Mike Hanlon, Lisa Hemingway, Pat Hosey, John Mackey, John club in the coming weeks. IACC President: John Cullinan (203) 506-5417 [email protected] Vice President: Lisa Hemingway (203) 927-6031 [email protected] McCormack, John O’Donovan, Rich Ranciato, Eileen Roxbee, and Aly Wheway. Sincerely, John Cullinan Treasurer: Michael Hanlon (203) 623-3945 [email protected] Financial Secretary: Madge Mulhall (203) 268-2037 [email protected] Recording Secretary: Theresa O’Brien (203) 640-3097 [email protected] Building Engineer: Dennis Hanlon (203) 503-1581 [email protected] RENOVATIONS NHGF&HC PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE NHGF&HC Our Renovation Kickoff meeting was a great success! We had quite a few The New Haven Gaelic Football and Hurling Club’s 31st Annual Banquet will President: Peter Burke (203) 623-5355 [email protected] Vice President: Sean Cox Please email [email protected] people show up with some great input.