The American Voice Anthology of Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

DJ Song list Songs by Artist DJ Song list Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions Title Versions -- 360 Ft Pez 50 Cent Adam & The Ants Al Green -- 360 Ft Pez - Live It Up DJ 21 Questions DJ Ant Music DJ Let's Stay Together We -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne Candy Shop DJ Goody Two Shoes DJ Al Stuart -- Chris Brown Ft Lil Wayne - DJ Hustler's Ambition DJ Stand And Deliver DJ Year Of The Cat DJ Loyal If I Can't DJ Adam Clayton & Larry Mullen Alan Jackson -- Illy In Da Club DJ Theme From Mission DJ Hi Chattahoochee DJ -- Illy - Tightrope (Clean) DJ Just A Li'l Bit DJ Impossible Don't Rock The Jukebox DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog 50 Cent Feat Justin Timberlake Adam Faith Gone Country DJ -- Jason Derulo Ft Snoop Dog DJ Ayo Technology DJ Poor Me DJ Livin' On Love DJ - Wiggle 50 Cent Feat Mobb Deep Adam Lambert Alan Parsons Project -- Th Amity Afflication Outta Control DJ Adam Lambert - Better Than I DJ Eye In The Sky 2010 Remix DJ -- Th Amity Afflication - Dont DJ Know Myself 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam Levin Alanis Morissette Lean On Me(Warning) If I Had You DJ 50 Cent Ft Eminem & Adam DJ Hand In My Pocket DJ - The Potbelleez Whataya Want From Me Ch Levine - My Life (Edited) Ironic DJ Shake It - The Potbelleez DJ Adam Sandler 50Cent Feat Ne-Yo You Oughta Know DJ (Beyonce V Eurythmics Remix (The Wedding Singer) I DJ Baby By Me DJ Alannah Myles Sweet Dreams DJ Wanna Grow Old With You 60 Ft Gossling Black Velvet DJ 01 - Count On Me - Bruno Marrs Adele 360 Ft Gossling - Price Of DJ Albert Lennard Count On Me - Bruno Marrs DJ Fame Adele - Skyfall DJ Springtime In L.A. -

The Uk's Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 1980'S

The Uk’s top 200 most requested songs in 1980’s 1. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson 2. Into the Groove - Madonna 3. Super Freak Part I - Rick James 4. Beat It - Michael Jackson 5. Funkytown - Lipps Inc. 6. Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) - Eurythmics 7. Don't You Want Me? - Human League 8. Tainted Love - Soft Cell 9. Like a Virgin - Madonna 10. Blue Monday - New Order 11. When Doves Cry - Prince 12. What I Like About You - The Romantics 13. Push It - Salt N Pepa 14. Celebration - Kool and The Gang 15. Flashdance...What a Feeling - Irene Cara 16. It's Raining Men - The Weather Girls 17. Holiday - Madonna 18. Thriller - Michael Jackson 19. Bad - Michael Jackson 20. 1999 - Prince 21. The Way You Make Me Feel - Michael Jackson 22. I'm So Excited - The Pointer Sisters 23. Electric Slide - Marcia Griffiths 24. Mony Mony - Billy Idol 25. I'm Coming Out - Diana Ross 26. Girls Just Wanna Have Fun - Cyndi Lauper 27. Take Your Time (Do It Right) - The S.O.S. Band 28. Let the Music Play - Shannon 29. Pump Up the Jam - Technotronic feat. Felly 30. Planet Rock - Afrika Bambaataa and The Soul Sonic Force 31. Jump (For My Love) - The Pointer Sisters 32. Fame (I Want To Live Forever) - Irene Cara 33. Let's Groove - Earth, Wind, and Fire 34. It Takes Two (To Make a Thing Go Right) - Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock 35. Pump Up the Volume - M/A/R/R/S 36. I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) - Whitney Houston 37. -

The Moral Mappings of South and North ANNUAL of EUROPEAN and GLOBAL STUDIES ANNUAL of EUROPEAN and GLOBAL STUDIES

The Moral Mappings of South and North ANNUAL OF EUROPEAN AND GLOBAL STUDIES ANNUAL OF EUROPEAN AND GLOBAL STUDIES Editors: Ireneusz Paweł Karolewski, Johann P. Arnason and Peter Wagner An annual collection of the best research on European and global themes, the Annual of European and Global Studies publishes issues with a specific focus, each addressing critical developments and controversies in the field. xxxxxx Peter Wagner xxxxxx The Moral Mappings of South and North Edited by Peter Wagner Edited by Peter Wagner Edited by Peter Cover image: xxxxx Cover design: www.paulsmithdesign.com ISBN: 978-1-4744-2324-3 edinburghuniversitypress.com 1 The Moral Mappings of South and North Annual of European and Global Studies An annual collection of the best research on European and global themes, the Annual of European and Global Studies publishes issues with a specific focus, each addressing critical developments and controversies in the field. Published volumes: Religion and Politics: European and Global Perspectives Edited by Johann P. Arnason and Ireneusz Paweł Karolewski African, American and European Trajectories of Modernity: Past Oppression, Future Justice? Edited by Peter Wagner Social Transformations and Revolutions: Reflections and Analyses Edited by Johann P. Arnason & Marek Hrubec www.edinburghuniversitypress.com/series/aegs Annual of European and Global Studies The Moral Mappings of South and North Edited by Peter Wagner Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

The Demographics and Production of Black Poetry

Syllabus Week 1: The Demographics and Production of Black Poetry Resident Faculty: Howard Rambsy Visiting Faculty: James Smethurst, Kathy Lou Schultz, Tyehimba Jess, Brenda Marie Osbey Led by Rambsy, the Week 1 readings, activities and lectures will address significant recurring topics in the discourse on African American poetry—black aesthetics, history, cultural pride, critiques of anti-black racism, music and performance—and concentrate on major trends, popular poets and canonical poems and genres. We will identify and discuss several major poets, including Amiri Baraka, Jayne Cortez, Nikki Giovanni, Carolyn Rodgers, and Dudley Randall whose works began circulating widely during the late 1960s and early 1970s. We will consider how the BAM intersects with and distinguishes itself from other related poetry movements like the Beat Generation. We look at the configuration of contemporary black poetry, as poets become identified by subject matter, region, movement and/or collective like Cave Canem Poets, the Affrilachian Poets, and the National Poetry Slam Movement that began in 1990. Rambsy, Kathy Lou Schultz, Smethurst and Graham will give lectures that provide NEH Summer Scholars with an overarching sense of poets in the field as well as major events and circumstances that have shaped African American poetry. As specialists who have written about poetry and literary history, Rambsy, Schultz, and Smethurst will collectively provide foundational concepts and material for understanding and teaching black poetry. The week will also include discussions and readings by poets Tyehimba Jess and Brenda Marie Osbey, which will give NEH Summer Scholars chances to consider persona poetry and the presence of history in contemporary poems. -

Transplanting Surrealism in Greece- a Scandal Or Not?

International Journal of Social and Educational Innovation (IJSEIro) Volume 2 / Issue 3/ 2015 Transplanting Surrealism in Greece- a Scandal or Not? NIKA Maklena University of Tirana, Albania E-mail: [email protected] Received 26.01.2015; Accepted 10.02. 2015 Abstract Transplanting the surrealist movement and literature in Greece and feedback from the critics and philological and journalistic circles of the time is of special importance in the history of Modern Greek Literature. The Greek critics and readers who were used to a traditional, patriotic and strictly rule-conforming literature would find it hard to accept such a kind of literature. The modern Greek surrealist writers, in close cooperation mainly with French surrealist writers, would be subject to harsh criticism for their surrealist, absurd, weird and abstract productivity. All this reaction against the transplanting of surrealism in Greece caused the so called “surrealist scandal”, one of the biggest scandals in Greek letters. Keywords: Surrealism, Modern Greek Literature, criticism, surrealist scandal, transplanting, Greek letters 1. Introduction When Andre Breton published the First Surrealist Manifest in 1924, Greece had started to produce the first modern works of its literature. Everything modern arrives late in Greece due to a number of internal factors (poetic collection of Giorgios Seferis “Mythistorima” (1935) is considered as the first modern work in Greek literature according to Αlexandros Argyriou, History of Greek Literature and its perception over years between two World Wars (1918-1940), volume Α, Kastanioti Publications, Athens 2002, pp. 534-535). Yet, on the other hand Greek writers continued to strongly embrace the new modern spirit prevailing all over Europe. -

A Unique Recording of "The Leaving of Liverpool"

0+ t<\1 5ummer/Fall V ~ 2008 E tJ) Webcasts -§i Odetta > \I) ~ :zV t V .. 1-> C Th:FS~I:::, i :~ O,:o~~:eb::': ~ C'U'OS from lh' ,'oS'oSofPm",' T,y"" V ¥e J Jd )1 n J J' IJJ JJ ,4,1 J. J }I;OJ j "W' J Dl 7 Now J'mlca-ving Li-vcr-pool, bound ouL for Fris-co Bay""'::::" I'm [cav-ing my sweet-heart be-hind me, but ['II U t W£ J J"Da ] I,LD 1)< J or j"rIJ~JJ IJ ) "J )1 ,LJ 311 come back and mar-ry you some-day_ Oh when I'm far a-waynt sea_ I'll nl-waysthink of you_ and the <l.) 4~' jJ J ;,1]:1 j J )IJ Ji J =1, 1J 0/) II " F' ) J. ~ IJ ) J. Jil t.__fl___ 19 day I'm Icav-ing Li-vcr-pooland the land ingstag!for sea. Sing fare you well, my own true love. when , ... LA E >Iun n I • J I} J J II _.--- F J J J J ~ m,. b" my do< , ling when I thinks of you. o gn"" u= American Folklite Center The Librar~ of Congress Folklife Center News AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER “The LeaVING OF LIVERPOOL” ODETTA AFC WEBCASTS IN THE AFC ARCHIVE 1930-2008 NOW ONLINE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Congressional Appointees: C. Kurt Dewhurst, Chair, Michigan Daniel Botkin, California Mickey Hart, California Dennis Holub, South Dakota William L. Kinney, Jr., South Carolina Charlie Seemann, Nevada Kay Kaufman Shelemay, Massachusetts Librarian Appointees: Jane Beck, Vice-chair, Vermont Maribel Alvarez, Arizona Read about a unique re Odetta Holmes Felious AFC has recently made Tom Rankin, North Carolina 15 3 cording of an iconic song, 13 Gordon was a remarkable webcasts available of its Donald Scott, Nevada and the colorful sailor who sang it singer, and a longtime friend of the 2008 public events. -

The Water Gun Song a Free Play for Two by Idris Goodwin

FREE PLAY: FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES JUNE 2020 Idris Goodwin The Water Gun Song A Free Play for two by Idris Goodwin SAM - Around 7 years old, brown skinned JULES - The Parent, Adult, brown skinned Any gender may play these parts Please perform the lines as written. Do not add or subtract, alter or repeat. Feel free however to emphasize, speed up, slow down--to feel it from the bottom of your feet. ________________________________________ 1 FREE PLAY: FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES JUNE 2020 Idris Goodwin SAM Are you listening? JULES Uh huh SAM: You just press this button and it takes off like - FOOSH! Just by pressing a button. Cindy has the best toys! JULES: That’s great Sam. SAM Yeah, so so awesome, so awesome! And that’s not all! That’s not all! JULES: No? SAM: They have a dog and a cat and an iguana. Can you believe that? JULES: And an iguana? SAM: Yup Yup His name is Ivan. Ivan Iguana. and guess what the cat’s name is? JULES?: Yeah that’s real nice. SAM Are you listening? 2 FREE PLAY: FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES JUNE 2020 Idris Goodwin JULES I am. Yes I am. SAM I asked if you could guess the cat’s name and you said “That’s real nice.” JULES I misunderstood you. I’m listening. See I put my phone down. SAM The cat's name. Guess. JULES What is the cat’s name? SAM Try and guess JULES Uh...Furball? SAM No! JULES Well? SAM Obama JULES Really? SAM Yup JULES 3 FREE PLAY: FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES JUNE 2020 Idris Goodwin That’s so cute SAM Yeah because he is half black and half white JULES I'm sorry, what? SAM Some of the cat’s fur is black and some is… JULES Sure. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

World Literature: the Unbearable Lightness of Thinking Globally1

Access Provided by Georgetown University Library at 12/13/11 11:38PM GMT Diaspora 12:1 2003 World Literature: The Unbearable Lightness of Thinking Globally1 Gregory Jusdanis The Ohio State University 1. Does literature have anything interesting to say about globaliza- tion? Is the work of literary critics germane to those analyzing today’s transnational flows of people, ideas, and goods? Many students of globalization, who work primarily in economics, political science, cultural studies, and journalism, would be skeptical of the claim that literary study could address their concerns. Indeed, they would be surprised to learn that Comparative Literature has been championing cosmopolitanism for more than a century, or that it had developed an international perspective on literary relations decades before they had. Comparative Literature, in fact, prefigured today’s transnational consciousness through its attempt to tran- scend the limits of individual national traditions and to investigate links among them. This makes the current malaise of Comparative Literature baf- fling. A discipline that promoted polyglossia and comparison for 100 years now finds itself in decline. Rather than emerging as a leading light in an academy so preoccupied with interdisciplinarity and difference, Comparative Literature has lost its glow. Most alarming of all, it has allowed English, Cultural Studies, and Globalization Studies to pursue a scorched-earth policy with respect to foreign languages. The discipline that spearheaded transnationalism in the humanities now finds itself in the rear guard. With some justification, Gayatri Spivak speaks of the death of the discipline. Her book, like so many studies of Comparative Lite- rature today, is written in an elegiac tone. -

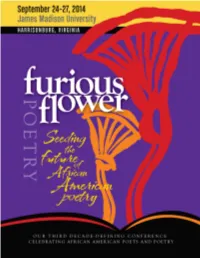

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa.