Pandora-Eve-Ava: Albert Lewin's Making of a “Secret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan

` ASX: MYG Mutiny Simplifies Deflector Plan 4 August 2014 Highlights: • New management complete “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study, simplifying and optimising the Deflector Project • Mutiny Board has resolved to pursue financing and development of the Deflector project based on the new mine plan • New mine plan reduces open pit volume by 80% based on both rock properties and ore thickness, and establishes early access to the underground mine • Processing capital and throughput revised to align with optimal underground production rate of 380,000 tonnes per annum • Payable metal of 365,000 gold ounces, 325,000 silver ounces, and 15,000 copper tonnes • Pre-production capital of $67.6M • C1 cash cost of $549 per gold ounce • All in sustaining cost of $723 per gold ounce • Exploration review completed with primary focus to be placed on the 7km long, under explored, “Deflector Corridor” Note: Payable metal and costs presented in the highlights are taken from the Life of Mine Inventory model (LOM Inventory). All currency in AUS$ unless marked. Mutiny Gold Ltd (ASX:MYG) (“Mutiny” or “The Company”) is pleased to announce that the new company management, under the leadership of Managing Director Tony James, has completed an internal “Mine Operators Review” of the Deflector gold, copper and silver project, located within the Murchison Region of Western Australia. The review was undertaken on detail associated with the 2013 Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) (ASX announcement 2 September, 2013). Tony James, -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

![1942-01-09 [P 10]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8873/1942-01-09-p-10-148873.webp)

1942-01-09 [P 10]

Radio DA IS OFFICERS OUT OUR WAY By J. B. Williams OUR BOARDING HOUSE .. with . Major HooPie Today’s Programs i-*" ^ ' r kuow whut yo’re im stiffVs N/well ,x don't M WE WANT TO TIP YEAH, WHEN ¥THANKS— A- LAUGH IU’ AT / DLL ADMIT Y TIME, COWBOSSI BLAME THE YOu'<^f IET PROMOTIONS TIMERS! JULIET—THERE'S H, HE'S BROKE ¥ ALWAYS BEEN AN V WMFD 1400 KC X LOOK LIKE A HOG I SPENT TWO OLD OFF, ^ Wilmington HERDER MONTHS IM IITHIMKI’D A WILD ANIMAL IN THE M HE SETS EASY TARGET Dance. AM’I’M A-GOIM’ ) </( TOR Mjf FRIDAY, JAN. 9 3:30—Let’s AW SOOWER 3:55—Transradio News. T’STAY THETAWAY, TILL /TH1 BRUSH / j HOUSE/—IF JAKE HITS A BEAR <6?TOUCH/— MUST BE A Majors Martin, Kendall Ad- TWO CAYS LOOK LIKE ^ jjp 7:30—Family Altar, Rev. J. A. Sulli- 4:00—Club Matinee. COWBOYS SPEWD MORE \ / YOU FOR A SILLY STREAKT van. 4:15—Monitor Views the News. TIME IU TH’ BRESH IW TOWU— / A REAL- LOAN,PRETENdXtRAPFOR }| w-fH 5V. Lee. vanced To Rank Of \ 7:45—Red, White and Blue Network. 4:30—Piano Ramblings—H. TRYIN)’ TO BE COWBOVS NIOVJ IE YOU SECTIOM HAWD YOU'RE HARD OF HEAR- MEN, INHERITED FROM News 4:45—Club Matinee—A. P. News. | j J[ 8:00—European Roundup. THAW IN) CABARETS I SIT OUE O' THAW A AND START TALKING ) WOMEN fA 8:10— News from our 5:00—Adventure Stories. Lieutenant-Colonel |NG GRANDPA,WHO jHWq Capital. -

Sexo, Amor Y Cine Por Salvador Sainz Introducción

Sexo, amor y cine por Salvador Sainz Introducción: En la última secuencia de El dormilón (The Sleeper, 1973), Woody Allen, desengañado por la evolución polí tica de una hipotética sociedad futura, le decí a escéptico a Diane Keaton: “Yo sólo creo en el sexo y en la muerte” . Evidentemente la desconcertante evolución social y polí tica de la última década del siglo XX parecen confirmar tal aseveración. Todos los principios é ticos del filósofo alemá n Hegel (1770-1831) que a lo largo de un siglo engendraron movimientos tan dispares como el anarquismo libertario, el comunismo autoritario y el fascismo se han desmoronado como un juego de naipes dejando un importante vací o ideológico que ha sumido en el estupor colectivo a nuestra desorientada generación. Si el siglo XIX fue el siglo de las esperanzas el XX ha sido el de los desengaños. Las creencias má s firmes y má s sólidas se han hundido en su propia rigidez. Por otra parte la serie interminable de crisis económica, polí tica y social de nuestra civilización parece no tener fin. Ante tanta decepción sólo dos principios han permanecido inalterables: el amor y la muerte. Eros y Tá natos, los polos opuestos de un mundo cada vez má s neurótico y vací o. De Tánatos tenemos sobrados ejemplos a cada cual má s siniestro: odio, intolerancia, guerras civiles, nacionalismo exacerbado, xenofobia, racismo, conservadurismo a ultranza, intransigencia, fanatismo… El Sé ptimo Arte ha captado esa evolución social con unas pelí culas cada vez má s violentas, con espectaculares efectos especiales que no nos dejan perder detalle de los aspectos má s sombrí os de nuestro entorno. -

Debbie Reynolds & Singin' in the Rain at WHBF 2013

Meet Legendary Actress, Comedienne, Singer, and Dancer And Join Us for a Very Special Park Stage Screening of Singin' in the Rain to Celebrate Reynolds' New Memoir, Unsinkable Including a Park Stage In-Conversation at 5:30 p.m., Book Soup In-Booth Signing at 6:15 p.m., followed by an Open-to the-Public Park Stage Screening at 7:00 p.m. For more information on schedule and start times, please visit WHBF.org for updates. About Debbie Reynolds and Unsinkable The definitive memoir by legendary actress and performer Debbie Reynolds—an entertaining and moving story of enduring friendships and unbreakable family bonds, of hitting bottom and rising to the top again—that offers a unique and deeply personal perspective on Hollywood and its elite, from the glory days of MGM to the present. In the closing pages of her 1988 autobiography Debbie: My Life , Debbie Reynolds wrote about finding her "brave, loyal, and loving" new husband. After two broken marriages, this third, she believed, was her lucky charm. But within a few years, Debbie discovered that he had betrayed her emotionally and financially, nearly destroying her life. Today, she writes, "When I read the optimistic ending of my last memoir now, I can't believe how naive I was when I wrote it. In Unsinkable, I look back at the many years since then, and share my memories of a film career that took me from the Miss Burbank Contest of 1948 to the work I did in 2012. To paraphrase Bette Davis: Fasten your seatbelts, I've had a bumpy ride." Unsinkable shines a spotlight on the resilient woman whose talent and passion for her work have endured for more than six decades. -

Ava Advocate Membership Please Donate! Follow Usfollow Us

Ava Advocate Membership The Ava Advocate membership program is designed to help finance the continued operation of the Ava Gardner Museum. With quarterly email newsletters to members, the museum will share information about events and new exhibits, as well as facts about the actress, her life, career, and loves. For a small annual fee, you can help us continue to preserve and share the Ava Gardner Collection for years to come. Become an Ava Advocate today and receive free admission for 12 months as well as 15% off gift shop purchases! Call the museum or go online to purchase your membership. Individual $36.00 Couple $45.00 F amily $60.00 Please Donate! As a non-profit museum, it’s only with the support of Ava’s fans that we can continue to honor and share her legacy. Please call us or donate online: ava-gardner-museum. myshopify.com/products/donations Follow Us Facebook: AvaGardner Twitter: @AvaMuseum Instagram: AvaGardnerOfficial The Ava Gardner Museum is Ava Gardner Museum 325 E. Market Street located in Historic Downtown Smithfield, NC 27577 Smithfield, just one mile Tel: 919-934-5830 [email protected] Smithfield, NC - I-95, Exit 95 from I-95, Exit 95. www.avagardner.org www.avagardner.org New exhibits, special events, and guest speakers are presented throughout Visit the Museum the year, giving Helpful Information Ava Gardner was born on December 24, visitors reasons to • Groups: If you have a group of 10 or more 1922, just seven miles east of Smithfield in a return again and transportation, the museum will provide a crossroads community called Grabtown. -

Schedule of the Films of Billy Wilder

je Museum of Modern Art November 1964 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART FILM LIBRARY PRESENTS THE FILMS OF BILLY WILDER Dec. 13.16 MENSCHEN AM SONNTAG (PEOPLE ON SUNDAY). I929. Robert Siodmak's cele brated study of proletarian life gave Wilder hie first taste of film making. (George Eastman House) 55 minutes. No English titles. Dec. IT-19 EMIL UND DIE DETEKTIVE. 1951. Small boys carry on psychological war fare against a crook in this Gerhard Lamprecht comedy for which Wilder helped write the script. (The Museum of Modern Art) 70 minutes. No English titles. Dec. 20-23 NINOTCHKA. 1939. Ernst Lubitsch's ironic satire on East-West relations just before World War II, in which Garbo gave her most delicately articulated performance with Melvyn Douglas, and for which Wilder, with Charles Brackett and Walter Reisch, wrote the script. Based on the story by Melchior Lengyel. (M-G-M) 110 minutes. Dec. 2k~26 MIDNIGHT. 1959. One of the most completely and purposely ridiculous examples of the era of screwball comedy, with a powerhouse of a cast, including Claudette Colbert, Don Ameche and John Barrymore, and Wilder and Brackett*s brilliant non-sequitur script. (MCA) 9U minutes. Dec. 27-30 HOLD BACK THE DAWN. 19*11. The plight of "stateless persons" in the late '30s and early 'UOs, with Olivia de Havllland, romantically yet convincingly dramatised by Wilder and Brackett. Directed by Mitchell Leisen. (MCA) 115 minutes. Dec. 31* THE MAJOR AND THE MINOR. 19te. This, the first film Wilder directed, Jan. -

Motion Picture Collection

ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY 949 East Second Street Library and Archives Tucson, AZ 85719 (520) 617-1157 [email protected] PC 090 Motion picture photograph collection, ca. 1914-1971 (bulk 1940s-1950s) DESCRIPTION Photographs of actors, scenes and sets from various movies, most filmed in Arizona. The largest part of the collection is taken of the filming of the movie “Arizona” including set construction, views behind-the-scenes, cameras, stage sets, equipment, and movie scenes. There are photographs of Jean Arthur, William Holden, and Lionel Banks. The premiere was attended by Hedda Hopper, Rita Hayworth, Melvyn Douglas, Fay Wray, Clarence Buddington Kelland, and many others. There are also photographs of the filming of “Junior Bonner,” “The Gay Desperado,” “The Three Musketeers,” and “Rio Lobo.” The “Gay Desperado” scenes include views of a Tucson street, possibly Meyer Avenue. Scenes from “Junior Bonner” include Prescott streets, Steve McQueen, Ida Lupino, Sam Peckinpah, and Robert Preston. Photographs of Earl Haley include images of Navajo Indian actors, Harry Truman, Gov. Howard Pyle, and director Howard Hawks. 3 boxes, 2 linear ft. HISTORICAL NOTE Old Tucson Movie Studio was built in 1940 as the stage set for the movie “Arizona.” For additional information about movies filmed in southern Arizona, see The Motion Picture History of Southern Arizona and Old Tucson (1912-1983) by Linwood C. Thompson, Call No. 791.43 T473. ACQUISITION These materials were donated by various people including George Chambers, Jack Van Ryder, Lester Ruffner, Merrill Woodmansee, Ann-Eve Mansfeld Johnson, Carol Clarke and Earl Haley and created in an artifical collection for improved access. -

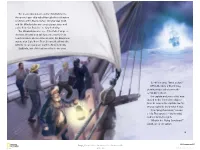

“What Is That?” Off in the Dark, a Frightening, Glowing Shape Sailed Across the Ocean Like a Ghost

The moon shined down on the Windcatcher as the great clipper ship sailed through the cold waters of the southern Pacific Ocean. The year was 1849, and the Windcatcher was carrying passengers and cargo from San Francisco to New York City. The Windcatcher was one of the fastest ships on the seas. She was now sailing south, near Chile in South America. She would soon enter the dangerous waters near Cape Horn. Then she would sail into the Atlantic Ocean and move north to New York City. Suddenly, one of the sailors yelled to the crew. “Look!” he cried. “What is that?” Off in the dark, a frightening, glowing shape sailed across the ocean like a ghost. The captain and some of his men moved to the front of the ship to look. As soon as the captain saw the strange sight, he knew what it was. “The Flying Dutchman,” he said softly. The captain looked worried and lost in his thoughts. “What is the Flying Dutchman?” asked one of the sailors. 2 3 Pirates often captured the ships when the crew resisted, they Facts about Pirates and stole the cargo without were sometimes killed or left violence. Often, just seeing at sea with little food or water. the pirates’ flag and hearing Other times, the pirates took A pirate is a robber at sea who great deal of valuable cargo their cannons was enough to the crew as slaves, or the crew steals from other ships out being shipped across the make the crew of these ships became pirates themselves! at sea. -

The Flying Dutchman Dichotomy: the Ni Ternational Right to Leave V

Penn State International Law Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 2 Dickinson Journal of International Law 1991 The lF ying Dutchman Dichotomy: The International Right to Leave v. The oS vereign Right to Exclude Suzanne McGrath Dale Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Dale, Suzanne McGrath (1991) "The Flying Dutchman Dichotomy: The nI ternational Right to Leave v. The oS vereign Right to Exclude," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 9: No. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol9/iss2/7 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Flying Dutchman Dichotomy: The International Right to Leave v. The Sovereign Right to Exclude' I. Introduction The Flying Dutchman is a mythic figure who is condemned to roam the world, never resting, never bringing his ship to port, until Judgement Day. Cursed by past crimes, he is forbidden to land and sails from sea to sea, seeking a peace which forever eludes him. The Dutchman created his own destiny. His acts caused his curse. He is ruled by Fate, not man-made law, or custom, or usage. But today, thanks to man's laws and man's ideas of what should be, there are many like the Dutchman who can find no port, no place to land. -

Ava Gardner – a Star of the Silver Screen

Ava Gardner – a Star of the Silver Screen Presented by William Markham Her Early Life Born 24 December 1922 Ava Lavinia Gardner in Grabtown, North Carolina Youngest of 7 children Lived on a Tobacco farm then a boarding house Money tight – not “Dirt Poor” At 18, her photo caught attention of MGM Earlier films one line bits or little better First notable film, The Killers, 1946 Photo that got Ava discovered Cover of Time Magazine 1951 Bit parts before she was famous 1941 Fancy Answers Girl at recital 1942 We do it because Girl at party 1943 Du Barry was a lady Perfume Girl 1944 Music for Millions Musician Some of her famous movies 1946 1951 1952 1953 1954 1959 1963 1964 1974 Marriages Mickey Rooney 1942 to 1943 Artie Shaw 1945 to 1946 Frank Sinatra 1951 to 1957 Some of her other romances Howard Hughes Robert Taylor George C Scott Robert Mitchum George C Scott Other Films Robert Taylor Robert Mitchum Lori Martin – National Velvet What Ava said about some actors: “The trouble was Frank and I were too much alike. My sister said that I was Frank in drag”. Frank Sinatra “Till death do us part would have been a whole lot sooner if we had tied the knot”. Howard Hughes “Bogie hated learning lines. He knew every trick in the book to mess up a scene and get a retake if he felt a scene was not going his way”. Humphrey Bogart “When he was loaded, he was terrifying. He would beat the hell out of me and have no idea the next morning what he had done”.