Manjiro Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Immigration History

CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) By HOSOK O Bachelor of Arts in History Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado 2000 Master of Arts in History University of Central Oklahoma Edmond, Oklahoma 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2010 © 2010, Hosok O ii CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE EARLY JAPANESE IMMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES DURING MEIJI TO TAISHO ERA (1868–1926) Dissertation Approved: Dr. Ronald A. Petrin Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael F. Logan Dr. Yonglin Jiang Dr. R. Michael Bracy Dr. Jean Van Delinder Dr. Mark E. Payton Dean of the Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For the completion of my dissertation, I would like to express my earnest appreciation to my advisor and mentor, Dr. Ronald A. Petrin for his dedicated supervision, encouragement, and great friendship. I would have been next to impossible to write this dissertation without Dr. Petrin’s continuous support and intellectual guidance. My sincere appreciation extends to my other committee members Dr. Michael Bracy, Dr. Michael F. Logan, and Dr. Yonglin Jiang, whose intelligent guidance, wholehearted encouragement, and friendship are invaluable. I also would like to make a special reference to Dr. Jean Van Delinder from the Department of Sociology who gave me inspiration for the immigration study. Furthermore, I would like to give my sincere appreciation to Dr. Xiaobing Li for his thorough assistance, encouragement, and friendship since the day I started working on my MA degree to the completion of my doctoral dissertation. -

APRIL 1995 R!' a ! DY April 1995 Number 936

APRIL 1995 R!' A ! DY April 1995 Number 936 I Earthquake epicen.,.s -IN THE SEA ?ABOVE THE SEA 4 The wave 22Weather prediction 6 What's going on? 24What is El Nino? 8 Knowledge is power 26Clouds, typhoons and hurricanes 10 Bioluminescence 28Highs, lows and fronts 11 Sounds in the sea 29Acid rain 12 Why is the ocean blue? 30 Waves 14 The sea floor 31The Gulf Stream 16 Going with the floe 32 The big picture: blue and littoral waters 18 Tides *THE ENVIRONMENT 34 TheKey West Campaign 19 Navyoceanographers 36 What's cookin' on USS Theodore Roosevek c 20Sea lanes of communication 38 GW Sailors put the squeeze on trash 40 Cleaning up on the West Coast 42Whale flies south after rescue 2 CHARTHOUSE M BEARINGS 48 SHIPMATES On the Covers Front cover: View of the Western Pacific takenfrom Apollo 13, in 1970. Photo courtesy of NASA. Opposite page: "Destroyer Man,"oil painting by Walter Brightwell. Back cover: EM3 Jose L. Tapia aboard USS Gary (FFG 51). Photo by JO1 Ron Schafer. so ” “I Charthouse Drug Education For Youth program seeks sponsors The Navy is looking for interested active and reserve commandsto sponsor the Drug Education For Youth (DEFY) program this summer. In 1994, 28 military sites across the nation helped more than 1,500 youths using the prepackaged innovative drug demand reduction program. DEFY reinforces self-esteem, goal- setting, decision-making and sub- stance abuse resistance skills of nine to 12-year-old children. This is a fully- funded pilot program of theNavy and DOD. DEFY combines a five to eight- day, skill-building summer camp aboard a military base with a year-long mentor program. -

May-June 293-WEB

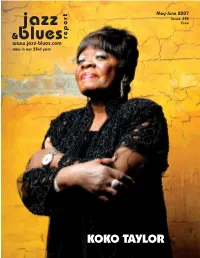

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Did You Receive This Copy of Jazzweek As a Pass Along?

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • Feb. 6, 2006 Volume 2, Number 11 • $7.95 In This Issue: Surprises at Berklee 60th Anniversary Concert . 4 Classical Meets Jazz in JALC ‘Jazz Suite’ Debut . 5 ALJO Embarks On Tour . 8 News In Brief . 6 Reviews and Picks . 15 Jazz Radio . 18 Smooth Jazz Radio. 25 Industry Legend Radio Panels. 24, 29 BRUCE LUNDVALL News. 4 Part One of our Two-part Q&A: page 11 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Jae Sinnett #1 Smooth Album – Richard Elliot #1 Smooth Single – Brian Simpson JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger n part one of our two part interview with Bruce Lundvall, the MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson Blue Note president tells music editor Tad Hendrickson that Iin his opinion radio indeed does sell records. That’s the good CONTRIBUTING EDITORS news. Keith Zimmerman Kent Zimmerman But Lundvall points out something that many others have CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ pointed out in recent years: radio doesn’t make hits. As he tells Tad, PHOTOGRAPHER “When I was a kid I would hear a new release and they would play Tom Mallison it over and over again. Not like Top 40, but over a period of weeks PHOTOGRAPHY you’d hear a tune from the new Hank Mobley record. That’s not Barry Solof really happening much any more.” Lundvall understands the state Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre of programming on mostly non-commercial jazz stations, and ac- ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy knowledges that kind of focused airplay doesn’t happen. Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or This ties into my question of last week – does mainstream jazz email: [email protected] radio play too much music that’s only good, but not great? I’ve SUBSCRIPTIONS: received a few comments; please email me with your thoughts on Free to qualified applicants this at [email protected]. -

K=O0 I. SONG- Part I INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS Mitsugu Sakihara

~1ASAT6 . MAISt;1 -- 1DMO¥ffiHI -KUROKAWA MINJ!K=o0 I. SONG- Part I INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS Mitsugu Sakihara Ryukyuan Resources at the University of Hawaii Okinawan Studies in the United St9-tes During the 1970s RYUKYUAN RESOURCES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII Introduction The resources for Ryukyuan studies at the University of Hawaii, reportedly the best outside of Japan, have attracted many scholars from Japan and other countries to Hawaii for research. For such study Ryukyu: A Bibliographical Guide to Okinawan Studies (1963) and Ryukyuan Research Resources at the University of Hawaii (1965), both by the late Dr. Shunzo Sakamaki, have served as the best intro duction. However, both books have long been out of print and are not now generally available. According to Ryukyuan Research Resources at the University of Hawaii, as of 1965, holdings totalled 4,197 titles including 3,594 titles of books and documents and 603 titles on microfilm. Annual additions for the past fifteen years, however, have increased the number considerably. The nucleus of the holdings is the Hawley Collection, supplemented by the books personally donated by Dro Shunzo Sakamaki, the Satsuma Collection, and recent acquisitions by the University of Hawaii. The total should be well over 5,000 titles. Hawley Collection The Hawley Collection represents the lifetime work of Mr. Frank Hawley, an English journalist and a well-known bibliophile who resided in Japan for more than 30 yearso When Hawley passed away in the winter of 1961 in Kyoto, Dr. Sakamaki, who happened 1 utsu no shi oyobi jo" [Song to chastize Ryukyu with preface], com posed by Priest Nanpo with the intention of justifying the expedition against Ryukyu in 1609 and of stimulating the morale of the troops. -

The 54Th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Child Neurology

Brain & Development 34 (2012) 410–458 The 54th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Child Neurology May 17–19, 2012 Royton Sapporo, Japan PROGRAM http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.braindev.2012.03.002 The 54th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Child Neurology / Brain & Development 34 (2012) 410–458 411 Presidential Lecture Novel therapies for pediatric neurological diseases: overview of the 54th Anual Meeting of Japanese Society of Child Neurology Tadashi Ariga* (Japan) *Department of Pediatrics, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine, Hokkaido, Japan Special Lecture Receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry Akira Suzuki* (Japan) *Professor Emeritus, Hokkaido University, Hokkaido, Japan Invited Lecture AAV-mediated gene therapy for lysosomal storage diseases with neurological features Miguel Sena-Esteves (USA) *Department of Neurology and Gene Therapy Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA [ Theme 1 ] Road to the future of regenerative medicine in child neurology Keynote Lecture Modelling the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative and neuro-developmental diseases using iPS cell thechnology Hideyuki Okano* (Japan) *Department of Physiology, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan Symposium : Regenerative medicine using iPS cells; is it a future therapy for pediatric neurological disorders? Chairs : Yukitoshi Takahashi1, Shinji Saitoh2 (Japan) 1National Epilepsy Center, Shizuoka Institute of Epilepsy and Neurological Disorders, Shizuoka, Japan 2Department of Pediatrics and Neonatology, -

Discografía De BLUE NOTE Records Colección Particular De Juan Claudio Cifuentes

CifuJazz Discografía de BLUE NOTE Records Colección particular de Juan Claudio Cifuentes Introducción Sin duda uno de los sellos verdaderamente históricos del jazz, Blue Note nació en 1939 de la mano de Alfred Lion y Max Margulis. El primero era un alemán que se había aficionado al jazz en su país y que, una vez establecido en Nueva York en el 37, no tardaría mucho en empezar a grabar a músicos de boogie woogie como Meade Lux Lewis y Albert Ammons. Su socio, Margulis, era un escritor de ideología comunista. Los primeros testimonios del sello van en la dirección del jazz tradicional, por entonces a las puertas de un inesperado revival en plena era del swing. Una sentida versión de Sidney Bechet del clásico Summertime fue el primer gran éxito de la nueva compañía. Blue Note solía organizar sus sesiones de grabación de madrugada, una vez terminados los bolos nocturnos de los músicos, y pronto se hizo popular por su respeto y buen trato a los artistas, que a menudo podían involucrarse en tareas de producción. Otro emigrante aleman, el fotógrafo Francis Wolff, llegaría para unirse al proyecto de su amigo Lion, creando un tandem particulamente memorable. Sus imágenes, unidas al personal diseño del artista gráfico Reid Miles, constituyeron la base de las extraordinarias portadas de Blue Note, verdadera seña de identidad estética de la compañía en las décadas siguientes mil veces imitada. Después de la Guerra, Blue Note iniciaría un giro en su producción musical hacia los nuevos sonidos del bebop. En el 47 uno de los jóvenes representantes del nuevo estilo, el pianista Thelonious Monk, grabó sus primeras sesiones Blue Note, que fue también la primera compañía del batería Art Blakey. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

Download (1MB)

THE BANSHO SHIRABESHO: A TRANSITIONAL INSTITUTION IN BAKUMATSU JAPAN by James Mitchell Hommes Bachelor of Arts, Calvin College, 1993 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary Master of Arts (IDMA) in East Asian Studies University of Pittsburgh 2004 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by James Mitchell Hommes It was defended on December 8, 2004 and approved by Thomas Rimer, Professor, East Asian Languages and Literature David O. Mills, Professor, East Asian Languages and Literature Richard Smethurst, Professor, History ii THE BANSHO SHIRABESHO: A TRANSITIONAL INSTITUTION IN BAKUMATSU JAPAN James M. Hommes, MA University of Pittsburgh, 2004 In the Bakumatsu period (1853-1868), Japan experienced many changes and challenges. One of these challenges was regarding how to learn from the West and how to use that knowledge in the building of Japan. One of the most important institutions for such Western learning was the Bansho Shirabesho, an institution created by the Tokugawa government in 1856 to translate Western materials, provide a school for Japanese scholars, and to censor the translations of Western works. This institution eventually gave language instruction in Dutch, English, French, German, and Russian and it also gave instruction in many other practical subjects such as military science and production. This thesis examines in detail how the Shirabesho was founded, what some of the initial difficulties were and how successful it was in accomplishing the tasks it was given. It also assesses the legacy of the Shirabesho in helping to bridge the transition between the Tokugawa period’s emphasis on feudal rank and the Meiji’s emphasis on merit. -

Japan America Grassroots Summit

www.jasgeorgia.org/2016-Grassroots-Summit Co-Organized by Supported by Table of Contents 1. Message of Support 14. Bus Drop Off Locations 2. Sponsors 15. Local Key Persons 3. Executive Summary 16. Closing Ceremony 4. What is this? 18. Stone Mountain Map 5. Summit History 19. Departures 6. Itinerary 20. Committee 7. Arrivals 21. Volunteers and Shifts 8. Atlanta Tours 25. Emergency Contacts 9. Opening Ceremony 26. Staff Contacts 11. Local Sessions 27. Hosting Tips The Origin of The Grassroots The friendship between Nakahama (John) Manjiro & Captain William Whitfield marks the beginning of Japan- America grassroots exchange. In 1841 an American whaling boat rescued five shipwrecked Japanese fishermen who were marooned on a remote Pacific island. Among the five was a fourteen year old boy called Manjiro. Manjiro's intelligent good nature soon earned him great respect among the American crew. He was given the name John, and taken back to Fairhaven Massachusetts to receive an American education. Under the care of the ship's captain William H. Whitfield, Manjiro studied not only English, science and navigation, but also about American culture and values- about freedom, democracy and hospitality. At that time Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa Shogunate, whose policy of isolationism meant that leaving the country was an offense punishable by death. After 10 years in America however Manjiro was determined to return home, to pass on the knowledge and goodwill he had received from Whitfield and the community of Fairhaven. Not long after Manjiro returned to Japan, Commodore Perry arrived calling for an end to isolationism, an event which lead to the birth of modern Japan. -

One and a Half Centuries Have Passed Since That Fateful Day When

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt THE BANSHO SHIRABESHO: A TRANSITIONAL INSTITUTION IN BAKUMATSU JAPAN by James Mitchell Hommes Bachelor of Arts, Calvin College, 1993 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The College of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary Master of Arts (IDMA) in East Asian Studies University of Pittsburgh 2004 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by James Mitchell Hommes It was defended on December 8, 2004 and approved by Thomas Rimer, Professor, East Asian Languages and Literature David O. Mills, Professor, East Asian Languages and Literature Richard Smethurst, Professor, History ii THE BANSHO SHIRABESHO: A TRANSITIONAL INSTITUTION IN BAKUMATSU JAPAN James M. Hommes, MA University of Pittsburgh, 2004 In the Bakumatsu period (1853-1868), Japan experienced many changes and challenges. One of these challenges was regarding how to learn from the West and how to use that knowledge in the building of Japan. One of the most important institutions for such Western learning was the Bansho Shirabesho, an institution created by the Tokugawa government in 1856 to translate Western materials, provide a school for Japanese scholars, and to censor the translations of Western works. This institution eventually gave language instruction in Dutch, English, French, German, and Russian and it also gave instruction in many other practical subjects such as military science and production. This thesis examines in detail how the Shirabesho was founded, what some of the initial difficulties were and how successful it was in accomplishing the tasks it was given. -

Title POPULATION PROBLEMS in the TOKUGAWA ERA Author(S) Honjo, Eijiro Citation Kyoto University Economic Review (1927), 2(2): 42

Title POPULATION PROBLEMS IN THE TOKUGAWA ERA Author(s) Honjo, Eijiro Citation Kyoto University Economic Review (1927), 2(2): 42-63 Issue Date 1927-12 URL https://doi.org/10.11179/ker1926.2.2_42 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University #fum;;;;::;;; M Kyoto University Eco'nomic Review MEMOIRS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITV OF KVOTO VOLUME II 1927 PUBLISHED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS IN TIlE IMPERIAL UNn'ERSITY OF KyOTO POPULATION PROBLEMS IN THE TOKUGAWA ERA 1. INCREASE OF THE POPULATION') In Japan, even in ancient times, there was an institu· tion for registering the names of members of families (Kosekt). In the Taiho·Ryo (i. e. the code amended during the year of Taiho-702 A.D.) that institution was placed under more exact regulations. Nevertheless, we cannot learn precisely the exact number of people at that time. In modern times, viz., the Tokugawa age, the number of people before the Kyoho period likewise remains unascertained. The order to reckon up the population was given by Yoshimune, the 8th Shogun of the Tokugawa dynasty. The two edicts, which were issued in the 6th year (1721) and in the 2nd month of the 11th year of Kyoho (1726), are of the utmost importance with reference to the problem. In the earlier decree, there was no order to examine the population and to report the number obtained from this examination. The number reported was only the registered number, which was already known to the officers at that time. But in the later decree, an examination and an actual counting of the people were evidently ordered.