Hickory Nut Carya Spp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA Spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION for COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE By Ana Maria Metaxas Approved: James Hill Craddock Jennifer Boyd Professor of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor of Biological and Environmental Sciences (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) Gregory Reighard Jeffery Elwell Professor of Horticulture Dean, College of Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE by Ana Maria Metaxas A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Chestnut cultivars were evaluated for their commercial applicability under the environmental conditions in Hamilton County, TN at 35°13ꞌ 45ꞌꞌ N 85° 00ꞌ 03.97ꞌꞌ W elevation 230 meters. In 2003 and 2004, 534 trees were planted, representing 64 different cultivars, varieties, and species. Twenty trees from each of 20 different cultivars were planted as five-tree plots in a randomized complete block design in four blocks of 100 trees each, amounting to 400 trees. The remaining 44 chestnut cultivars, varieties, and species served as a germplasm collection. These were planted in guard rows surrounding the four blocks in completely randomized, single-tree plots. In the analysis, we investigated our collection predominantly with the aim to: 1) discover the degree of acclimation of grower- recommended cultivars to southeastern Tennessee climatic conditions and 2) ascertain the cultivars’ ability to survive in the area with Cryphonectria parasitica and other chestnut diseases and pests present. -

Scientific Name Common Name NATURAL ASSOCIATIONS of TREES and SHRUBS for the PIEDMONT a List

www.rainscapes.org NATURAL ASSOCIATIONS OF TREES AND SHRUBS FOR THE PIEDMONT A list of plants which are naturally found growing with each other and which adapted to the similar growing conditions to each other Scientific Name Common Name Acer buergeranum Trident maple Acer saccarum Sugar maple Acer rubrum Red Maple Betula nigra River birch Trees Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Fagus grandifolia American beech Maple Woods Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip-tree, yellow poplar Liquidamber styraciflua Sweetgum Magnolia grandiflora Southern magnolia Amelanchier arborea Juneberry, Shadbush, Servicetree Hamamelis virginiana Autumn Witchhazel Shrubs Ilex opaca American holly Ilex vomitoria*** Yaupon Holly Viburnum acerifolium Maple leaf viburnum Aesulus parvilflora Bottlebrush buckeye Aesulus pavia Red buckeye Carya ovata Shadbark hickory Cornus florida Flowering dogwood Halesia carolina Crolina silverbell Ilex cassine Cassina, Dahoon Ilex opaca American Holly Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip-tree, yellow poplar Trees Ostrya virginiana Ironwood Prunus serotina Wild black cherry Quercus alba While oak Quercus coccinea Scarlet oak Oak Woods Quercus falcata Spanish red oak Quercus palustris Pin oak Quercus rubra Red oak Quercus velutina Black oak Sassafras albidum Sassafras Azalea nudiflorum Pinxterbloom azalea Azalea canescens Piedmont azalea Ilex verticillata Winterberry Kalmia latifolia Mountain laurel Shrubs Rhododenron calendulaceum Flame azalea Rhus copallina Staghorn sumac Rhus typhina Shining sumac Vaccinium pensylvanicum Low-bush blueberry Magnolia -

Conservation Assessment for Butternut Or White Walnut (Juglans Cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region

Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region 2003 Jan Schultz Hiawatha National Forest Forest Plant Ecologist (906) 228-8491 This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Juglans cinerea L. (butternut). This is an administrative review of existing information only and does not represent a management decision or direction by the U. S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was gathered and reported in preparation of this document, then subsequently reviewed by subject experts, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if the reader has information that will assist in conserving the subject taxon, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Butternut or White walnut (Juglans cinerea) L. 2 Table Of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION / OBJECTIVES.......................................................................7 BIOLOGICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION..............................8 Species Description and Life History..........................................................................................8 SPECIES CHARACTERISTICS...........................................................................9 -

The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity

Article The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity Mauro De Feudis 1,* , Gloria Falsone 1, Gilmo Vianello 2 and Livia Vittori Antisari 1 1 Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, Via Fanin, 40, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (L.V.A.) 2 Centro Sperimentale per lo Studio e l’Analisi del Suolo (CSSAS), Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 June 2020; Accepted: 19 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Recently, several hectares of abandoned chestnut forests (ACF) were recovered into chestnut stands for nut or timber production; however, the effects of such practice on soil mineral horizon properties are unknown. This work aimed to (1) identify the better chestnut forest management to maintain or to improve the soil properties during the ACF recovery, and (2) give an insight into the effect of unmanaged to managed forest conversion on soil properties, taking in consideration sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest ecosystems. The investigation was conducted in an experimental chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest located in the northern part of the Apennine chain (Italy). We identified an ACF, a chestnut forest for wood production (WCF), and chestnut forests 1 for nut production with a tree density of 98 and 120 plants ha− (NCFL and NCFH, respectively). WCF, NCFL and NCFH stands are the result of the ACF recovery carried out in 2004. -

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids . oaks, birches, evening primroses . a major group of the woody plants (trees/shrubs) present at your sites The Wind Pollinated Trees • Alternate leaved tree families • Wind pollinated with ament/catkin inflorescences • Nut fruits = 1 seeded, unilocular, indehiscent (example - acorn) *Juglandaceae - walnut family Well known family containing walnuts, hickories, and pecans Only 7 genera and ca. 50 species worldwide, with only 2 genera and 4 species in Wisconsin Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Leaves pinnately compound, alternate (walnuts have smallest leaflets at tip) Leaves often aromatic from resinous peltate glands; allelopathic to other plants Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family The chambered pith in center of young stems in Juglans (walnuts) separates it from un- chambered pith in Carya (hickories) Juglans regia English walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Trees are monoecious Wind pollinated Female flower Male inflorescence Juglans nigra Black walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Male flowers apetalous and arranged in pendulous (drooping) catkins or aments on last year’s woody growth Calyx small; each flower with a bract CA 3-6 CO 0 A 3-∞ G 0 Juglans cinera Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Female flowers apetalous and terminal Calyx cup-shaped and persistant; 2 stigma feathery; bracted CA (4) CO 0 A 0 G (2-3) Juglans cinera Juglans nigra Butternut, white -

Nut Production, Marketing Handout

Nut Production, Marketing Handout Why grow nuts in Iowa??? Nuts can produce the equivalent of a white-collar salary from a part-time job. They are up to 12 times more profitable per acre than corn was, even back when corn was $8/bushel. Nuts can accomplish the above with just a fraction of the investment in capital, land, and labor. Nuts can be grown in a biologically diverse perennial polyculture system with the following benefits: Builds soil instead of losing it to erosion Little or no chemical inputs needed Sequesters CO2 and builds soil organic matter Increases precipitation infiltration and storage, reduces runoff, building resilience against drought Produces high-quality habitat for wildlife, pollinating insects, and beneficial soil microbes Can build rural communities by providing a good living and a high quality of life for a whole farm family, on a relatively few acres If it’s so great, why doesn’t everybody do it? “Time Preference” economic principle: the tendency of people to prefer a smaller reward immediately over having to wait for a larger reward. Example: if an average person was to be given the choice between the following…. # 1. $10,000 cash right now, tax-free, no strings, or #2. Work part-time for 10 years with no pay, but after 10 years receive $100,000 per year, every year, for the rest of his/her life, and then for his/her heirs, in perpetuity… Most would choose #1, the immediate, smaller payoff. This is a near-perfect analogy for nut growing. Nut growing requires a substantial up-front investment with no return for the first five years, break-even not until eight to ten years, then up to $10,000 per acre or more at maturity, 12-15 years. -

Monsanto Improved Fatty Acid Profile MON 87705 Soybean, Petition 09-201-01P

Monsanto Improved Fatty Acid Profile MON 87705 Soybean, Petition 09-201-01p OECD Unique Identifier: MON-87705-6 Final Environmental Assessment September 2011 Agency Contact Cindy Eck USDA, APHIS, BRS 4700 River Road, Unit 147 Riverdale, MD 20737-1237 Phone: (301) 734-0667 Fax: (301) 734-8669 [email protected] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’S TARGET Center at (202) 720–2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326–W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250–9410 or call (202) 720–5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Mention of companies or commercial products in this report does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over others not mentioned. USDA neither guarantees nor warrants the standard of any product mentioned. Product names are mentioned solely to report factually on available data and to provide specific information. This publication reports research involving pesticides. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. MONSANTO 87705 SOYBEAN TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................ iv 1 PURPOSE AND NEED ........................................................................................................ -

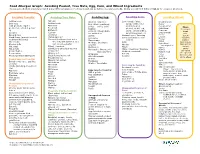

Avoiding Peanut, Tree Nuts, Egg, Corn, and Wheat Ingredients Common Food Allergens May Be Listed Many Different Ways on Food Labels and Can Be Hidden in Common Foods

Food Allergen Graph: Avoiding Peanut, Tree Nuts, Egg, Corn, and Wheat Ingredients Common food allergens may be listed many different ways on food labels and can be hidden in common foods. Below you will find different labels for common allergens. Avoiding Peanuts: Avoiding Tree Nuts: Avoiding Egg: Avoiding Corn: Avoiding Wheat: Artificial nuts Almond Albumin / albumen Corn - meal, flakes, Bread Crumbs Beer nuts Artificial nuts Egg (dried, powdered, syrup, solids, flour, Bulgur Cold pressed, expeller Brazil nut solids, white, yolk) niblets, kernel, Cereal extract Flour: pressed or extruded peanut Beechnut Eggnog alcohol, on the cob, Club Wheat all-purpose Butternut oil Globulin / Ovoglobulin starch, bread,muffins Conscous bread Goobers Cashew Fat subtitutes sugar/sweetener, oil, Cracker meal cake Durum Ground nuts Chestnut Livetin Caramel corn / flavoring durum Einkorn Mandelonas (peanuts soaked Chinquapin nut Lysozyme Citric acid (may be corn enriched Emmer in almond flavoring) Coconut (really is a fruit not a based) graham Mayonnaise Farina Mixed nuts tree nut, but classified as a Grits high gluten Meringue (meringue Hydrolyzed Monkey nuts nut on some charts) high protein powder) Hominy wheat protein Nut meat Filbert / hazelnut instant Ovalbumin Maize Kamut Gianduja -a chocolate-nut mix pastry Nut pieces Ovomucin / Ovomucoid / Malto / Dextrose / Dextrate Matzoh Peanut butter Ginkgo nut Modified cornstarch self-rising Ovotransferrin Matzoh meal steel ground Peanut flour Hickory nut Polenta Simplesse Pasta stone ground Peanut protein hydrolysate -

Carya Ovata (Mill.) K

shagbark hickory Juglandaceae Carya ovata (Mill.) K. Koch symbol: CAOV2 Leaf: Alternate, pinnately compound, 8 to 14 inches long with 5 (sometimes 7) leaflets, lateral leaflets are obovate to lanceolate, terminal leaflets are much larger than the laterals, margins serrate and ciliate, rachis stout and mostly glabrous; green above and paler below. Flower: Species is monoecious; male flowers are yellow-green catkins, hanging in 3's, 2 to 3 inches long; females are very short, in clusters at the end of branches, both appear spring. Fruit: Nearly round, 1 1/2 to 2 inches, with a very thick husk; nut is distinctly 4-ribbed, and the seed is sweet and delicious; maturing in fall. Twig: Stout and usually tomentose, but may be somewhat pubescent near terminal bud, numerous lighter lenticels; leaf scars are raised, 3-lobed to semicircular - best described as a "monkey face"; terminal bud is large, brown, and pubescent, covered with 3 to 4 brown scales, more elongated than other hickories. Bark: At first smooth and gray, later broken into long, wide plates attached at the middle, curving away from the trunk resulting in a coarsely shaggy appearance. Form: A tall tree reaching over 120 feet tall with a straight trunk and an open round to oblong crown. Looks like: shellbark hickory - red hickory - mockernut hickory - pignut hickory Additional Range Information: External Links: Carya ovata is native to North USDAFS Silvics of North America America. Range may be expanded by USDAFS Additional Silvics planting. See states reporting Landowner Factsheet shagbark hickory. USDA Plants Database Horticulture. -

Juglandaceae (Walnuts)

A start for archaeological Nutters: some edible nuts for archaeologists. By Dorian Q Fuller 24.10.2007 Institute of Archaeology, University College London A “nut” is an edible hard seed, which occurs as a single seed contained in a tough or fibrous pericarp or endocarp. But there are numerous kinds of “nuts” to do not behave according to this anatomical definition (see “nut-alikes” below). Only some major categories of nuts will be treated here, by taxonomic family, selected due to there ethnographic importance or archaeological visibility. Species lists below are not comprehensive but representative of the continental distribution of useful taxa. Nuts are seasonally abundant (autumn/post-monsoon) and readily storable. Some good starting points: E. A. Menninger (1977) Edible Nuts of the World. Horticultural Books, Stuart, Fl.; F. Reosengarten, Jr. (1984) The Book of Edible Nuts. Walker New York) Trapaceae (water chestnuts) Note on terminological confusion with “Chinese waterchestnuts” which are actually sedge rhizome tubers (Eleocharis dulcis) Trapa natans European water chestnut Trapa bispinosa East Asia, Neolithic China (Hemudu) Trapa bicornis Southeast Asia and South Asia Trapa japonica Japan, jomon sites Anacardiaceae Includes Piastchios, also mangos (South & Southeast Asia), cashews (South America), and numerous poisonous tropical nuts. Pistacia vera true pistachio of commerce Pistacia atlantica Euphorbiaceae This family includes castor oil plant (Ricinus communis), rubber (Hevea), cassava (Manihot esculenta), the emblic myrobalan fruit (of India & SE Asia), Phyllanthus emblica, and at least important nut groups: Aleurites spp. Candlenuts, food and candlenut oil (SE Asia, Pacific) Archaeological record: Late Pleistocene Timor, Early Holocene reports from New Guinea, New Ireland, Bismarcks; Spirit Cave, Thailand (Early Holocene) (Yen 1979; Latinis 2000) Rincinodendron rautanenii the mongongo nut, a Dobe !Kung staple (S. -

Sweet Pecan Plant Fact Sheet

Plant Fact Sheet status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, state PECAN noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh.) Description and Adaptation K. Koch Pecan is a large tree to 150 feet with a broad rounded Plant Symbol = CAIL2 crown. It is the largest of all the hickories. It produces flowers from March to May with both male and female flowers on the same tree. Leaves are alternate, odd- Contributed by: USDA NRCS East Texas Plant Materials pinnately compound with 9-17 leaflets. The fruit is a nut Center 1 to 2 inches long and ½ to l inch in diameter. The nut is encased in a thin husk which is divided into sections which open in the fall at maturity. The bark is grayish brown to light brown with flattened ridges and narrow fissures. The wood is reddish brown with lighter sapwood, brittle and hard. Pecan grows best in loam soils which are well drained without prolonged flooding. Pecan is adapted to areas with a minimum of 30 inches of average rainfall. Pecan distribution from USDA-NRCS Plants database Establishment Due to stratification requirements for the nut to sprout, establishment is best with nursery grown seedlings which are planted in the fall or early winter. In mass plantings Robert Mohlenbrock bare root seedlings can be planted by hand or machine. USDA, NRCS, Wetland Science Institute Care should be taken with root placement and planting @PLANTS depth. The root collar should be planted at the same depth as grown in the nursery. Alternate Names Sweet pecan, Illinois nut, faux hickory, pecan hickory, Management pecan nut, pecan tree Weed control and fertilization are important considerations for maximizing nut production. -

Carya Eral Roots

VIEWPOINT HORTSCIENCE 51(6):653–663. 2016. nut (seed) has hypogeal germination and forms a dominate taproot with abundant lat- Carya eral roots. Leaves are odd-pinnately com- Crop Vulnerability: pound with 11–17 leaflets, borne in alternate L.J. Grauke1 arrangement, with reduction in leaflet number, size, and pubescence as the tree matures. USDA–ARS Pecan Breeding and Genetics, 10200 FM 50, Somerville, TX Seedlings have long juvenility (5–12 years) 77879 and bear imperfect flowers at different loca- tions on the tree. Male and female flowers Bruce W. Wood mature at different times (dichogamy). Male USDA–ARS Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, 21 flowers are borne on staminate catkins in Dunbar Road, Byron, GA 31008 fascicles of three, with catkin groups formed on opposite sides of each vegetative bud, Marvin K. Harris sometimes with a second pair above, borne Department of Entomology (Professor Emeritus), Texas A&M University, opposite each other, at 90° to the first. The College Station, TX 77843 catkins are borne at the base of the current season’s growth or from more distal buds of Additional index words. Carya illinoinensis, germplasm, diversity, breeding, repository, the previous season whose vegetative axis characterization aborts after pollen shed. This pattern of catkin formation is characteristic of all members of Abstract. Long-established native tree populations reflect local adaptations. Represen- section Apocarya, but is distinct from the other tation of diverse populations in accessible ex situ collections that link information on sections of the genus (Figs. 2–4). Pollen is phenotypic expression to information on spatial and temporal origination is the most produced in very large quantities and is carried efficient means of preserving and exploring genetic diversity, which is the foundation of by wind.