Trees of Valley Forge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA Spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION for COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION

CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE By Ana Maria Metaxas Approved: James Hill Craddock Jennifer Boyd Professor of Biological Sciences Assistant Professor of Biological and Environmental Sciences (Director of Thesis) (Committee Member) Gregory Reighard Jeffery Elwell Professor of Horticulture Dean, College of Arts and Sciences (Committee Member) A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of the Graduate School CHESTNUT (CASTANEA spp.) CULTIVAR EVALUATION FOR COMMERCIAL CHESTNUT PRODUCTION IN HAMILTON COUNTY, TENNESSEE by Ana Maria Metaxas A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Science May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Chestnut cultivars were evaluated for their commercial applicability under the environmental conditions in Hamilton County, TN at 35°13ꞌ 45ꞌꞌ N 85° 00ꞌ 03.97ꞌꞌ W elevation 230 meters. In 2003 and 2004, 534 trees were planted, representing 64 different cultivars, varieties, and species. Twenty trees from each of 20 different cultivars were planted as five-tree plots in a randomized complete block design in four blocks of 100 trees each, amounting to 400 trees. The remaining 44 chestnut cultivars, varieties, and species served as a germplasm collection. These were planted in guard rows surrounding the four blocks in completely randomized, single-tree plots. In the analysis, we investigated our collection predominantly with the aim to: 1) discover the degree of acclimation of grower- recommended cultivars to southeastern Tennessee climatic conditions and 2) ascertain the cultivars’ ability to survive in the area with Cryphonectria parasitica and other chestnut diseases and pests present. -

Tree Mycorrhizal Type Predicts Within‐Site Variability in the Storage And

Received: 6 December 2017 | Accepted: 8 February 2018 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14132 PRIMARY RESEARCH ARTICLE Tree mycorrhizal type predicts within-site variability in the storage and distribution of soil organic matter Matthew E. Craig1 | Benjamin L. Turner2 | Chao Liang3 | Keith Clay1 | Daniel J. Johnson4 | Richard P. Phillips1 1Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA Abstract 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Forest soils store large amounts of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), yet how predicted Balboa, Ancon, Panama shifts in forest composition will impact long-term C and N persistence remains 3Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Management, Institute of Applied Ecology, poorly understood. A recent hypothesis predicts that soils under trees associated Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang, with arbuscular mycorrhizas (AM) store less C than soils dominated by trees associ- China ated with ectomycorrhizas (ECM), due to slower decomposition in ECM-dominated 4Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, USA forests. However, an incipient hypothesis predicts that systems with rapid decom- position—e.g. most AM-dominated forests—enhance soil organic matter (SOM) sta- Correspondence Matthew E. Craig, Department of Biology, bilization by accelerating the production of microbial residues. To address these Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. contrasting predictions, we quantified soil C and N to 1 m depth across gradients of Email: [email protected] ECM-dominance in three temperate forests. By focusing on sites where AM- and Funding information ECM-plants co-occur, our analysis controls for climatic factors that covary with myc- Biological and Environmental Research, Grant/Award Number: DE-SC0016188; orrhizal dominance across broad scales. -

Erigenia : Journal of the Southern Illinois Native Plant Society

ERIGENIA THE LIBRARY OF THE DEC IS ba* Number 13 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 1994 ^:^;-:A-i.,-CS..;.iF/uGN SURVEY Conference Proceedings 26-27 September 1992 Journal of the Eastern Illinois University Illinois Native Plant Society Charleston Erigenia Number 13, June 1994 Editor: Elizabeth L. Shimp, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial St., Harrisburg, IL 62946 Copy Editor: Floyd A. Swink, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Publications Committee: John E. Ebinger, Botany Department, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920 Ken Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. 1 Box 495 A, Westville, IL 61883 Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 Lawrence R. Stritch, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial Su, Harrisburg, IL 62946 Cover Design: Christopher J. Whelan, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Cover Illustration: Jean Eglinton, 2202 Hazel Dell Rd., Springfield, IL 62703 Erigenia Artist: Nancy Hart-Stieber, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Executive Committee of the Society - April 1992 to May 1993 President: Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 President-Elect: J. William Hammel, Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, Springfield, IL 62701 Past President: Jon J. Duerr, Kane County Forest Preserve District, 719 Batavia Ave., Geneva, IL 60134 Treasurer: Mary Susan Moulder, 918 W. Woodlawn, Danville, IL 61832 Recording Secretary: Russell R. Kirt, College of DuPage, Glen EUyn, IL 60137 Corresponding Secretary: John E. Schwegman, Illinois Department of Conservation, Springfield, IL 62701 Membership: Lorna J. Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. -

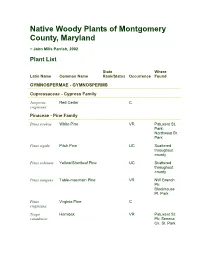

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

Castanea Sativa Mill

Forest Ecology and Forest Management Group Tree factsheet images at pages 3, 4, 5, 6 Castanea sativa Mill. taxonomy author, year Miller, … synonym C. vesca Gaertn. Family Fagaceae Eng. Name Sweet Chestnut tree, Spanish Chestnut, European Chestnut Dutch name Tamme kastanje subspecies - varieties - hybrids - cultivars, frequently used references Weeda 2003, Nederlandse oecologische flora, vol.1 (Dutch) PFAF database http://www.pfaf.org/index.html morphology crown habit tree, round max. height (m) 30 max. dbh (cm) 300 actual size Europe 2000? years old, d(..) 197, Etna, Sicily , Italy actual size The Netherlands year 1600-1700, d (130) 270, h 25, Kabouterboom, Beek-Ubbergen year 1810-1820, d(130) 149, h 30 leaf length (cm) 10-27 leaf petiole (cm) 2-3 leaf colour upper surface green leaf colour under surface green leaves arrangement alternate flowering June flowering plant monoecious flower monosexual flower diameter (cm) 1 flower male catkins length (cm) 8-12 pollination wind fruit; length burr (Dutch: bolster) containing 2-3 nuts; 6-8 cm fruit petiole (cm) 1 seed; length nut; 5-6 cm seed-wing length (cm) - weight 1000 seeds (g) 300-1000 seeds ripen September seed dispersal rodents: Apodemus -species – Wood mice - bosmuizen rodents: Sciurus vulgaris - Squirrel - Eekhoorn birds: Garulus glandarius – Jay –Gaai habitat natural distribution Europe, West Asia in N.W. Europe since 9000 B.C. natural areas The Netherlands forests geological landscape types The Netherlands loss-covered terraces, ice pushed ridges (Hoek 1997) forested areas The Netherlands loamy and sandy soils. area Netherlands < 1700 (2002, Probos) % of forest trees in the Netherlands < 0,7 (2002, Probos) soil type pH-KCl indifferent soil fertility nutrient medium to rich light highly shade tolerant as a sapling, shade tolerant when mature shade tolerance 3.2 (0=no tolerance to 5=max. -

Nutritive Value and Degradability of Leaves from Temperate Woody Resources for Feeding Ruminants in Summer

3rd European Agroforestry Conference Montpellier, 23-25 May 2016 Silvopastoralism (poster) NUTRITIVE VALUE AND DEGRADABILITY OF LEAVES FROM TEMPERATE WOODY RESOURCES FOR FEEDING RUMINANTS IN SUMMER Emile JC 1*, Delagarde R 2, Barre P 3, Novak S 1 Corresponding author: [email protected] mailto:(1) INRA, UE 1373 FERLUS, 86600 Lusignan, France (2) INRA, UMR 1348 INRA-Agrocampus Ouest, 35590 Saint-Gilles, France (3) INRA, UR 4 URP3F, 86600 Lusignan, France 1/ Introduction Integrating agroforestry in livestock farming systems may be a real opportunity in the current climatic, social and economic conditions. Trees can contribute to improve welfare of grazing ruminants. The production of leaves from woody plants may also constitute a forage resource for livestock (Papanastasis et al. 2008) during periods of low grasslands production (summer and autumn). To know the potential of leaves from woody plants to be fed by ruminants, including dairy females, the nutritive value of these new forages has to be evaluated. References on nutritive values that already exist for woody plants come mainly from tropical or Mediterranean climatic conditions (http://www.feedipedia.org/) and very few data are currently available for the temperate regions. In the frame of a long term mixed crop-dairy system experiment integrating agroforestry (Novak et al. 2016), a large evaluation of leaves from woody resources has been initiated. The objective of this evaluation is to characterise leaves of woody forage resources potentially available for ruminants (hedgerows, coppices, shrubs, pollarded trees), either directly by browsing or fed after cutting. This paper presents the evaluation of a first set of 12 woody resources for which the feeding value is evaluated through their protein and fibre concentrations, in vitro digestibility (enzymatic method) and effective ruminal degradability. -

The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity

Article The Conversion of Abandoned Chestnut Forests to Managed Ones Does Not Affect the Soil Chemical Properties and Improves the Soil Microbial Biomass Activity Mauro De Feudis 1,* , Gloria Falsone 1, Gilmo Vianello 2 and Livia Vittori Antisari 1 1 Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, Via Fanin, 40, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (L.V.A.) 2 Centro Sperimentale per lo Studio e l’Analisi del Suolo (CSSAS), Alma Mater Studiorum—University of Bologna, 40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 June 2020; Accepted: 19 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Recently, several hectares of abandoned chestnut forests (ACF) were recovered into chestnut stands for nut or timber production; however, the effects of such practice on soil mineral horizon properties are unknown. This work aimed to (1) identify the better chestnut forest management to maintain or to improve the soil properties during the ACF recovery, and (2) give an insight into the effect of unmanaged to managed forest conversion on soil properties, taking in consideration sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest ecosystems. The investigation was conducted in an experimental chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) forest located in the northern part of the Apennine chain (Italy). We identified an ACF, a chestnut forest for wood production (WCF), and chestnut forests 1 for nut production with a tree density of 98 and 120 plants ha− (NCFL and NCFH, respectively). WCF, NCFL and NCFH stands are the result of the ACF recovery carried out in 2004. -

Nut Production, Marketing Handout

Nut Production, Marketing Handout Why grow nuts in Iowa??? Nuts can produce the equivalent of a white-collar salary from a part-time job. They are up to 12 times more profitable per acre than corn was, even back when corn was $8/bushel. Nuts can accomplish the above with just a fraction of the investment in capital, land, and labor. Nuts can be grown in a biologically diverse perennial polyculture system with the following benefits: Builds soil instead of losing it to erosion Little or no chemical inputs needed Sequesters CO2 and builds soil organic matter Increases precipitation infiltration and storage, reduces runoff, building resilience against drought Produces high-quality habitat for wildlife, pollinating insects, and beneficial soil microbes Can build rural communities by providing a good living and a high quality of life for a whole farm family, on a relatively few acres If it’s so great, why doesn’t everybody do it? “Time Preference” economic principle: the tendency of people to prefer a smaller reward immediately over having to wait for a larger reward. Example: if an average person was to be given the choice between the following…. # 1. $10,000 cash right now, tax-free, no strings, or #2. Work part-time for 10 years with no pay, but after 10 years receive $100,000 per year, every year, for the rest of his/her life, and then for his/her heirs, in perpetuity… Most would choose #1, the immediate, smaller payoff. This is a near-perfect analogy for nut growing. Nut growing requires a substantial up-front investment with no return for the first five years, break-even not until eight to ten years, then up to $10,000 per acre or more at maturity, 12-15 years. -

Brewing Beer with Native Plants (Seasonality)

BREWING BEER WITH INDIANA NATIVE PLANTS Proper plant identification is important. Many edible native plants have poisonous look-alikes! Availability/When to Harvest Spring. Summer. Fall Winter . Year-round . (note: some plants have more than one part that is edible, and depending on what is being harvested may determine when that harvesting period is) TREES The wood of many native trees (especially oak) can be used to age beer on, whether it be barrels or cuttings. Woods can also be used to smoke the beers/malts as well. Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis): Needles and young twigs can be brewed into a tea or added as ingredients in cooking, similar flavoring to spruce. Tamarack (Larix laricina): Bark and twigs can be brewed into a tea with a green, earthy flavor. Pine species (Pinus strobus, Pinus banksiana, Pinus virginiana): all pine species have needles that can be made into tea, all similar flavor. Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana): mature, dark blue berries and young twigs may be made into tea or cooked with, similar in flavor to most other evergreen species. Pawpaw (Asimina triloba): edible fruit, often described as a mango/banana flavor hybrid. Sassafras (Sassafras albidum): root used to make tea, formerly used to make rootbeer. Similarly flavored, but much more earthy and bitter. Leaves have a spicier, lemony taste and young leaves are sometimes used in salads. Leaves are also dried and included in file powder, common in Cajun and Creole cooking. Northern Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis): Ripe, purple-brown fruits are edible and sweet. Red Mulberry (Morus rubra): mature red-purple-black fruit is sweet and juicy. -

Naturalization of Almond Trees (Prunus Dulcis) in Semi-Arid Regions

*Manuscript Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Naturalization of almond trees (Prunus dulcis) in semi-arid 10 11 regions of the Western Mediterranean. 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 1 2 1,3 19 Pablo Homet-Gutierrez , Eugene W. Schupp , José M. Gómez * 20 1Departamento de Ecología, Facultad de Ciencias. Universidad de Granada, España. 21 2 22 Department of Wildland Resources and the Ecology Center. Utah State University. USA. 23 3Dpt de Ecología Evolutiva y Funcional, Estación Experimental de Zonas Aridas (EEZA-CSIC), 24 25 Almería, España. 26 27 28 *Corresponding author 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 1 63 64 65 Abstract 1 Agricultural land abandonment is rampant in present day Europe. A major consequence of this 2 3 phenomenon is the re-colonization of these areas by the original vegetation. However, some 4 agricultural, exotic species are able to naturalize and colonize these abandoned lands. In this 5 6 study we explore the ability of almonds (Prunus dulcis D.A. Webb.) to establish in abandoned 7 croplands in semi-arid areas of SE Iberian Peninsula. Domesticated during the early Holocene 8 9 in SW Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean, the almond has spread as a crop all over the world. 10 We established three plots adjacent to almond orchards on land that was abandoned and 11 12 reforested with Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) and Holm oak (Quercus ilex L.) about 20 13 years ago. -

Monsanto Improved Fatty Acid Profile MON 87705 Soybean, Petition 09-201-01P

Monsanto Improved Fatty Acid Profile MON 87705 Soybean, Petition 09-201-01p OECD Unique Identifier: MON-87705-6 Final Environmental Assessment September 2011 Agency Contact Cindy Eck USDA, APHIS, BRS 4700 River Road, Unit 147 Riverdale, MD 20737-1237 Phone: (301) 734-0667 Fax: (301) 734-8669 [email protected] The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’S TARGET Center at (202) 720–2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326–W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250–9410 or call (202) 720–5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Mention of companies or commercial products in this report does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over others not mentioned. USDA neither guarantees nor warrants the standard of any product mentioned. Product names are mentioned solely to report factually on available data and to provide specific information. This publication reports research involving pesticides. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. MONSANTO 87705 SOYBEAN TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................ iv 1 PURPOSE AND NEED ........................................................................................................ -

Localized Gene Expression Changes During Adventitious Root Formation in Black Walnut (Juglans Nigra L.)

Tree Physiology 38, 877–894 doi:10.1093/treephys/tpx175 Research paper Localized gene expression changes during adventitious root formation in black walnut (Juglans nigra L.) Micah E. Stevens1, Keith E. Woeste2 and Paula M. Pijut2,3 1Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University, Hardwood Tree Improvement and Regeneration Center (HTIRC), 715 West State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; 2USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, HTIRC, 715 West State Street, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; 3Corresponding author ([email protected]) Received May 31, 2017; accepted December 20, 2017; published online January 25, 2018; handling Editor Danielle Way Cutting propagation plays a large role in the forestry and horticulture industries where superior genotypes need to be clonally multiplied. Integral to this process is the ability of cuttings to form adventitious roots. Recalcitrance to adventitious root develop- ment is a serious hurdle for many woody plant propagation systems including black walnut (Juglans nigra L.), an economically valuable species. The inability of black walnut to reliably form adventitious roots limits propagation of superior genotypes. Adventitious roots originate from different locations, and root induction is controlled by many environmental and endogenous factors. At the molecular level, however, the regulation of adventitious root formation is still poorly understood. In order to eluci- date the transcriptional changes during adventitious root development in black walnut, we used quantitative real-time polymer- ase chain reaction to measure the expression of nine key genes regulating root formation in other species. Using our previously developed spatially explicit timeline of adventitious root development in black walnut softwood cuttings, we optimized a laser capture microdissection protocol to isolate RNA from cortical, phloem fiber and phloem parenchyma cells throughout adventi- tious root formation.