New York State Museum Associates Richard S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tree Mycorrhizal Type Predicts Within‐Site Variability in the Storage And

Received: 6 December 2017 | Accepted: 8 February 2018 DOI: 10.1111/gcb.14132 PRIMARY RESEARCH ARTICLE Tree mycorrhizal type predicts within-site variability in the storage and distribution of soil organic matter Matthew E. Craig1 | Benjamin L. Turner2 | Chao Liang3 | Keith Clay1 | Daniel J. Johnson4 | Richard P. Phillips1 1Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA Abstract 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Forest soils store large amounts of carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), yet how predicted Balboa, Ancon, Panama shifts in forest composition will impact long-term C and N persistence remains 3Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Management, Institute of Applied Ecology, poorly understood. A recent hypothesis predicts that soils under trees associated Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang, with arbuscular mycorrhizas (AM) store less C than soils dominated by trees associ- China ated with ectomycorrhizas (ECM), due to slower decomposition in ECM-dominated 4Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, USA forests. However, an incipient hypothesis predicts that systems with rapid decom- position—e.g. most AM-dominated forests—enhance soil organic matter (SOM) sta- Correspondence Matthew E. Craig, Department of Biology, bilization by accelerating the production of microbial residues. To address these Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. contrasting predictions, we quantified soil C and N to 1 m depth across gradients of Email: [email protected] ECM-dominance in three temperate forests. By focusing on sites where AM- and Funding information ECM-plants co-occur, our analysis controls for climatic factors that covary with myc- Biological and Environmental Research, Grant/Award Number: DE-SC0016188; orrhizal dominance across broad scales. -

Erigenia : Journal of the Southern Illinois Native Plant Society

ERIGENIA THE LIBRARY OF THE DEC IS ba* Number 13 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 1994 ^:^;-:A-i.,-CS..;.iF/uGN SURVEY Conference Proceedings 26-27 September 1992 Journal of the Eastern Illinois University Illinois Native Plant Society Charleston Erigenia Number 13, June 1994 Editor: Elizabeth L. Shimp, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial St., Harrisburg, IL 62946 Copy Editor: Floyd A. Swink, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Publications Committee: John E. Ebinger, Botany Department, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920 Ken Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. 1 Box 495 A, Westville, IL 61883 Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 Lawrence R. Stritch, U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Shawnee National Forest, 901 S. Commercial Su, Harrisburg, IL 62946 Cover Design: Christopher J. Whelan, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Cover Illustration: Jean Eglinton, 2202 Hazel Dell Rd., Springfield, IL 62703 Erigenia Artist: Nancy Hart-Stieber, The Morton Arboretum, Lisle, IL 60532 Executive Committee of the Society - April 1992 to May 1993 President: Kenneth R. Robertson, Illinois Natural History Survey, 607 E. Peabody Dr., Champaign, IL 61820 President-Elect: J. William Hammel, Illinois Environmental Protection Agency, Springfield, IL 62701 Past President: Jon J. Duerr, Kane County Forest Preserve District, 719 Batavia Ave., Geneva, IL 60134 Treasurer: Mary Susan Moulder, 918 W. Woodlawn, Danville, IL 61832 Recording Secretary: Russell R. Kirt, College of DuPage, Glen EUyn, IL 60137 Corresponding Secretary: John E. Schwegman, Illinois Department of Conservation, Springfield, IL 62701 Membership: Lorna J. Konsis, Forest Glen Preserve, R.R. -

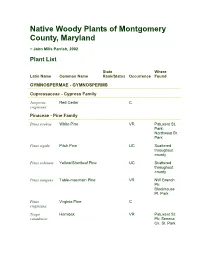

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland

Native Woody Plants of Montgomery County, Maryland ~ John Mills Parrish, 2002 Plant List State Where Latin Name Common Name Rank/Status Occurrence Found GYMNOSPERMAE - GYMNOSPERMS Cupressaceae - Cypress Family Juniperus Red Cedar C virginiana Pinaceae - Pine Family Pinus strobus White Pine VR Patuxent St. Park; Northwest Br. Park Pinus rigida Pitch Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus echinata Yellow/Shortleaf Pine UC Scattered throughout county Pinus pungens Table-mountain Pine VR NW Branch Pk; Blockhouse Pt. Park Pinus Virginia Pine C virginiana Tsuga Hemlock VR Patuxent St. canadensis Pk; Seneca Ck. St. Park ANGIOSPERMAE - MONOCOTS Smilacaceae - Catbrier Family Smilax glauca Glaucous Greenbrier C Smilax hispida Bristly Greenbrier UC/R Potomac (syn. S. River & Rock tamnoides) Ck. floodplain Smilax Common Greenbrier C rotundifolia ANGIOSPERMAE - DICOTS Salicaceae - Willow Family Salix nigra Black Willow C Salix Carolina Willow S3 R Potomac caroliniana River floodplain Salix interior Sandbar Willow S1/E VR/X? Plummer's & (syn. S. exigua) High Is. (1902) (S.I.) Salix humilis Prairie Willow R Travilah Serpentine Barrens Salix sericea Silky Willow UC Little Bennett Pk.; NW Br. Pk. (Layhill) Populus Big-tooth Aspen UC Scattered grandidentata across county - (uplands) Populus Cottonwood FC deltoides Myricaceae - Bayberry Family Myrica cerifera Southern Bayberry VR Little Paint Branch n. of Fairland Park Comptonia Sweet Fern VR/X? Lewisdale, peregrina (pers. com. C. Bergmann) Juglandaceae - Walnut Family Juglans cinerea Butternut S2S3 R -

Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps

Appendix 11.5.1: Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps These distribution maps are for 116 aquatic vascular macrophyte species (Table 1). Aquatic designation follows habitat descriptions in Haines and Vining (1998), and includes submergent, floating and some emergent species. See Appendix 11.4 for list of species. Also included in Appendix 11.4 is the number of HUC-10 watersheds from which each taxon has been recorded, and the county-level distributions. Data are from nine sources, as compiled in the MABP database (plus a few additional records derived from ancilliary information contained in reports from two fisheries surveys in the Upper St. John basin organized by The Nature Conservancy). With the exception of the University of Maine herbarium records, most locations represent point samples (coordinates were provided in data sources or derived by MABP from site descriptions in data sources). The herbarium data are identified only to township. In the species distribution maps, town-level records are indicated by center-points (centroids). Figure 1 on this page shows as polygons the towns where taxon records are identified only at the town level. Data Sources: MABP ID MABP DataSet Name Provider 7 Rare taxa from MNAP lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 8 Lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 35 Acadia National Park plant survey C. Greene et al. 63 Lake plant surveys A. Dieffenbacher-Krall 71 Natural Heritage Database (rare plants) MNAP 91 University of Maine herbarium database C. Campbell 183 Natural Heritage Database (delisted species) MNAP 194 Rapid bioassessment surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 207 Invasive aquatic plant records MDEP Maps are in alphabetical order by species name. -

Aristolochia Serpentaria L

New England Plant Conservation Program Aristolochia serpentaria L. Virginia Snakeroot Conservation and Research Plan for New England Prepared by: Dorothy J. Allard, Ph.D. Analytical Resources, LLC P.O. Box 279 East Montpelier, VT 05651 For: New England Wild Flower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, MA 01701 508/877-7630 e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.newfs.org Approved, Regional Advisory Council, 2002 SUMMARY Aristolochia serpentaria L., commonly known as Virginia Snakeroot, is a perennial herb in the Aristolochiaceae. Several varieties have been described in the past, but they are no longer recognized in most taxonomic manuals. Aristolochia serpentaria occurs in 26 eastern states and is common in the southern and central part of its range, while becoming rare along its northern periphery. It is listed as a Division 2 species in Flora Conservanda (Brumback and Mehrhoff et al. 1996). Connecticut is the only New England state in which it is found, where it occurs at 12 known sites in ten towns. It grows in a variety of upland forest communities, but is more likely to be found in dry, somewhat rich, rocky, deciduous or mixed deciduous-coniferous woods in Connecticut. Farther south, it also has broad environmental requirements, occupying many upland soil and forest types. Population trends for the species in Connecticut are unclear. One new population was discovered in 2001. Monitoring in 2001 of eight extant sites found that two populations had decreased, three had increased, and one had stayed the same. Several known populations are threatened by habitat modification, invasive species, or site fragility. Two extant populations have not been surveyed for several years. -

Brewing Beer with Native Plants (Seasonality)

BREWING BEER WITH INDIANA NATIVE PLANTS Proper plant identification is important. Many edible native plants have poisonous look-alikes! Availability/When to Harvest Spring. Summer. Fall Winter . Year-round . (note: some plants have more than one part that is edible, and depending on what is being harvested may determine when that harvesting period is) TREES The wood of many native trees (especially oak) can be used to age beer on, whether it be barrels or cuttings. Woods can also be used to smoke the beers/malts as well. Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis): Needles and young twigs can be brewed into a tea or added as ingredients in cooking, similar flavoring to spruce. Tamarack (Larix laricina): Bark and twigs can be brewed into a tea with a green, earthy flavor. Pine species (Pinus strobus, Pinus banksiana, Pinus virginiana): all pine species have needles that can be made into tea, all similar flavor. Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana): mature, dark blue berries and young twigs may be made into tea or cooked with, similar in flavor to most other evergreen species. Pawpaw (Asimina triloba): edible fruit, often described as a mango/banana flavor hybrid. Sassafras (Sassafras albidum): root used to make tea, formerly used to make rootbeer. Similarly flavored, but much more earthy and bitter. Leaves have a spicier, lemony taste and young leaves are sometimes used in salads. Leaves are also dried and included in file powder, common in Cajun and Creole cooking. Northern Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis): Ripe, purple-brown fruits are edible and sweet. Red Mulberry (Morus rubra): mature red-purple-black fruit is sweet and juicy. -

2018 Aquatic Plant Guide

The Borough of Mountain Lakes The Aquatic Plants of Mountain Lakes Created March 2017 Borough of Introduction to Aquatic Plants Mountain Lakes 400 Boulevard Aquatic plants in a lake come in many different sizes, shapes and Mountain Lakes, NJ function. This diversity is similar to the different components of a 07046 forest, having low grasses, understory shrubs, diminutive trees and vines, and canopy forming trees. Different aquatic plants inhabit dif- 973-334-3131 ferent ecological niches depending on a myriad of physical, chemical http://mtnlakes.org and biological conditions. Although many lake recreational users view aquatic plants as nui- sance “weeds”, a balanced native aquatic plant community has sev- eral important ecological functions. These include: Shoreline Buffer Sediment Stabilization Wildlife Habitat Aesthetics In this guide: Nutrient Uptake Red indicates an Aquatic plants fall into the following broad categories. Submersed Invasive species aquatic plants grow along the lake bottom and are entirely sub- merged save perhaps for flowers or seeds. Floating-leaf plants in- Blue indicates a clude duckweeds and lilies, and have leaves on the surface of a lake. Native species Emergent plants have roots in standing water, but the majority of Green indicates an the plant occurs above the water’s surface. Finally, some aquatic Algal species plant growth is actually macro-algae. Below are a list of icons for the aquatic plants in this guide. Call to Action! ICON KEY Please Contact Rich Sheola, Borough Manager [email protected] Submersed Emergent Floating-leaf Macro-algae PAGE 2 THE AQUATIC PLANTS O F MOUNTAIN LAKES CREATED MARCH 2017 Summary of Aquatic Plants at Mt. -

Aristolochic Acids Tract Urothelial Cancer Had an Unusually High Incidence of Urinary- Bladder Urothelial Cancer

Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition For Table of Contents, see home page: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/roc Aristolochic Acids tract urothelial cancer had an unusually high incidence of urinary- bladder urothelial cancer. CAS No.: none assigned Additional case reports and clinical investigations of urothelial Known to be human carcinogens cancer in AAN patients outside of Belgium support the conclusion that aristolochic acids are carcinogenic (NTP 2008). The clinical stud- First listed in the Twelfth Report on Carcinogens (2011) ies found significantly increased risks of transitional-cell carcinoma Carcinogenicity of the urinary bladder and upper urinary tract among Chinese renal- transplant or dialysis patients who had consumed Chinese herbs or Aristolochic acids are known to be human carcinogens based on drugs containing aristolochic acids, using non-exposed patients as sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity from studies in humans and the reference population (Li et al. 2005, 2008). supporting data on mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Evidence of car- Molecular studies suggest that exposure to aristolochic acids is cinogenicity from studies in experimental animals supports the find- also a risk factor for Balkan endemic nephropathy (BEN) and up- ings in humans. per-urinary-tract urothelial cancer associated with BEN (Grollman et al. 2007). BEN is a chronic tubulointerstitial disease of the kidney, Cancer Studies in Humans endemic to Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, Bulgaria, and Romania, that has The evidence for carcinogenicity in humans is based on (1) findings morphology and clinical features similar to those of AAN. It has been of high rates of urothelial cancer, primarily of the upper urinary tract, suggested that exposure to aristolochic acids results from consump- among individuals with renal disease who had consumed botanical tion of wheat contaminated with seeds of Aristolochia clematitis (Ivic products containing aristolochic acids and (2) mechanistic studies 1970, Hranjec et al. -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al. -

Don Robinson State Park Species Count: 544

Trip Report for: Don Robinson State Park Species Count: 544 Date: Multiple Visits Jefferson County Agency: MODNR Location: LaBarque Creek Watershed - Vascular Plants Participants: Nels Holmberg, WGNSS, MONPS, Justin Thomas, George Yatskievych This list was compiled by Nels Holmbeg over a period of > 10 years Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acalypha gracilens slender three-seeded mercury Euphorbiaceae 3 5 Acalypha monococca (A. gracilescens var. monococca) one-seeded mercury Euphorbiaceae 3 5 Acalypha rhomboidea rhombic copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 1 3 Acalypha virginica Virginia copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 2 3 Acer rubrum var. undetermined red maple Sapindaceae 5 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple Sapindaceae 2 -3 Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae/Anthemideae 1 3 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry Ranunculaceae 8 5 Adiantum pedatum var. pedatum northern maidenhair fern Pteridaceae Fern/Ally 6 1 Agalinis tenuifolia (Gerardia, A. tenuifolia var. common gerardia Orobanchaceae 4 -3 macrophylla) Ageratina altissima var. altissima (Eupatorium rugosum) white snakeroot Asteraceae/Eupatorieae 2 3 Agrimonia parviflora swamp agrimony Rosaceae 5 -1 Agrimonia pubescens downy agrimony Rosaceae 4 5 Agrimonia rostellata woodland agrimony Rosaceae 4 3 Agrostis perennans upland bent Poaceae/Aveneae 3 1 * Ailanthus altissima tree-of-heaven Simaroubaceae 0 5 * Ajuga reptans carpet bugle Lamiaceae 0 5 Allium canadense var. undetermined wild garlic Liliaceae 2 3 Allium stellatum wild onion Liliaceae 6 5 * Allium vineale field garlic Liliaceae 0 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 3 Ambrosia bidentata lanceleaf ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 4 Amelanchier arborea var. arborea downy serviceberry Rosaceae 6 3 Amorpha canescens lead plant Fabaceae/Faboideae 8 5 Amphicarpaea bracteata hog peanut Fabaceae/Faboideae 4 0 Andropogon gerardii var. -

Pignut Hickory

Carya glabra (Mill.) Sweet Pignut Hickory Juglandaceae Walnut family Glendon W. Smalley Pignut hickory (Curya glabru) is a common but not -22” F) have been recorded within the range. The abundant species in the oak-hickory forest associa- growing season varies by latitude and elevation from tion in Eastern United States. Other common names 140 to 300 days. are pignut, sweet pignut, coast pignut hickory, Mean annual relative humidity ranges from 70 to smoothbark hickory, swamp hickory, and broom hick- 80 percent with small monthly differences; daytime ory. The pear-shaped nut ripens in September and relative humidity often falls below 50 percent while October and is an important part of the diet of many nighttime humidity approaches 100 percent. wild animals. The wood is used for a variety of Mean annual hours of sunshine range from 2,200 products, including fuel for home heating. to 3,000. Average January sunshine varies from 100 to 200 hours, and July sunshine from 260 to 340 Habitat hours. Mean daily solar radiation ranges from 12.57 to 18.86 million J mf (300 to 450 langleys). In Native Range January daily radiation varies from 6.28 to 12.57 million J m+ (150 to 300 langleys), and in July from The range of pignut hickory (fig. 1) covers nearly 20.95 to 23.04 million J ti (500 to 550 langleys). all of eastern United States (11). It extends from According to one classification of climate (20), the Massachusetts and the southwest corner of New range of pignut hickory south of the Ohio River, ex- Hampshire westward through southern Vermont and cept for a small area in Florida, is designated as extreme southern Ontario to central Lower Michigan humid, mesothermal. -

Guidance for Landowners Participating in the Indiana Bats Forestry Project

The Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey (CWF) is a non-profit conservation organization dedicated to New Jersey’s rare wildlife, including the 71 species protected by law and the hundreds of others considered Species of Conservation Concern. Since our inception in 1998, CWF has worked to protect our wildlife resources through research, management, outreach, and education. Guidance for Landowners Participating in the Indiana Bats Forestry Project Project Summary: This project is designed to engage New Jersey’s landowners, farmers, and land managers in protecting one of the most endangered land mammal groups in the United States: bats. Bats are an extremely important part of our environment and are one of the most beneficial animals to people, yet more than half of America’s bat species are in severe decline because of factors including habitat loss, disturbance to hibernating colonies and summer roosts, persecution by man, and diseases Indiana & little brown bats such as White-nose Syndrome (WNS), which threatens entire hibernating colonies where it occurs. WNS was confirmed in New Jersey in January 2009 and now affects nine states (2009). NJ is home to nine bat species, including the endangered Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis). Indiana bats inhabit forests and wooded wetland areas in summer, where they roost and raise their young under the loose bark of certain living trees (such as shagbark hickory) and a variety of dead trees (elms, oaks, maples, sycamores, hickories, etc.). Ideal roost locations include riparian zones, along a wetland or water body, or otherwise near a water feature providing a reliable insect prey base.